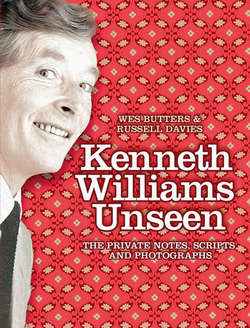

Читать книгу Kenneth Williams Unseen: The private notes, scripts and photographs - Russell Davies - Страница 5

ОглавлениеIntroduction by Russell Davies

‘On boarding the plane I was stuck next to this woman who asked: “They all call you Mister Williams…are you famous? Should I know you?” I told her “No – I’m nobody dear…just got a yard and a half in Who’s Who, that’s all”’

Diary, 13 April 1983

It is possible that we already know, or think we know, more about Kenneth Williams than we’ve ever learned about any previous British actor, classical or comical. Yet there is much more to be known, as this book will show. The public appetite for intimate details of his life, which has not diminished in the twenty years since his death, was created by him. Williams knew that his was a most unusual, possibly unique, personality type, and the glimpses he publicly offered of himself – those half-hinted confessions and protestations of celibacy – were not simply made as teases to keep his public interested. He himself wanted to know, I think, how people would regard him if they came to know more of the truth of who he was. To that end he would sneak out fragments of his authentic self. An opportunity was lost in his autobiography, Just Williams, the kind of carefully judged performance that could have been read on Radio 4 without expurgation. A franker book might have helped him, and us.

As Kenneth was aware, the world from which he disappeared in 1988 was already changing quickly. But he had never been ashamed of his own retro tastes – the Victorian poetry, the music from Buxtehude to Fauré but not much further – and with his health restored he might have found the energy to convince an increasingly shallow public of the worth of his ruminative pursuits. As an 82 year old in 2008, he could have held his place in the media firmament alongside surviving contemporaries like Sir David Attenborough and David Jacobs, his fellow-broadcasters, and his old friend Stanley Baxter, all born in 1926. (Indeed, Kenneth was almost exactly two months older than Her Majesty the Queen.)

Parts of his comedy world ought by now to be in ruins. The Carry On tradition was insular even in its own day, laden with funny foreigners and semi-inflatable, perpetually shocked, seaside-postcard women. But we’ve heard so much about the cast members and their off-screen interactions (which have even been dramatized in a National Theatre play, Terry Johnson’s Cleo, Camping, Emmanuelle and Dick) that we now read the on-screen narrative twice as it goes along: once in its own silly terms, and once in terms of the ways the actors are surviving the material, and in some cases one another. By contrast, the campery of the Kenneth Horne radio performances seems almost uncorroded, and has lately become a mainstay of BBC7, the digital-radio archival network. And though the parlour game Just a Minute has now been running longer without Williams than with him, one can still hear younger panellists putting into practice the lessons he taught, under the guidance of David Hatch, about playing the game ‘outrageously’. The extent to which his career relied on the continuity of BBC work has perhaps been underestimated before, but it is thoroughly explored in these pages.

This book began, in a sense, at the end, with the death of Kenneth Williams, so it’s with that topic that we do begin. In my view, his death itself is not very mysterious – for debatability it’s not in the class of, say, Robert Maxwell’s demise – yet it does continue to be debated. Kenneth was much loved, in both a show business and a personal sense. Many of his friends and fans will forever argue hotly against the notion of his suicide, and in favour of misadventure. Meanwhile the open verdict which the Coroner actually returned stands as a perpetual invitation to reconsider the case.

But some important opinions have never been heard. Neither in 1988, nor in 1993 when my selection from his diaries was published, was any comment made by the friends named in Kenneth’s will: his agent, Michael Anderson; his companion on cultural travels, the businessman Michael Whittaker; his neighbour, Paul Richardson; or his godson, Robert Chidell. The world knew nothing of these gentlemen at the time, and they very reasonably preferred to keep it that way. Now, thanks to the persuasion of Wes Butters, they have spoken, enabling us to present the fullest picture of the circumstances of Kenneth’s death that posterity can hope for. It seemed unlikely that the pathologist employed on the case would add much detail to that picture, especially as he now works in New Zealand; but again, Wes’s initiative prevailed, and Dr Pease has contributed a remarkably vivid account of his involvement.

To understand the participation of the Chidell family in Kenneth’s life, it’s necessary to know something of the history of the actor John Vere, a friend of his from the 1950s and a fellow cast-member of Tony Hancock’s TV show. Robert Chidell is John Vere’s great-nephew, though John had been dead fifteen years by the time Robert was born. Vere committed suicide in 1961, at the age of only 45 (he ‘played older’, as they say in the profession). Although Kenneth found him cranky and annoying towards the end, in kinder times he’d been fond of Vere’s gentle presence. Isobel Chidell, Vere’s sister, tells his story, which runs as a kind of forecast of Kenneth’s; though Vere enjoyed a much more aristocratic professional grounding. Vere’s story stands for several others that were played out on the borders of Kenneth’s life: actors, directors and writers who started out with the same bright hopes, and gradually settled (or not) for something well short of stardom.

One family figure in the story who has remained seriously under-illuminated has been Kenneth’s sister, Pat. She, like Ken, was regarded with some wonderment by those who met her socially, chiefly on account of her unforgettable voice, a growling cigarette-fuelled basso that was very nearly male. At the time of the diaries’ publication Pat was still alive, and it would not have been fair to tell her full story, as revealed in one of the early diary volumes. The fact that Charlie Williams was not her real father explained much of the tension between daughter and Dad, and indeed between Pat and Kenneth. For the same reasons of tact, the subject was not raised, either, when Pat’s only sound interview was recorded, in 1995, for my Radio 4 programme I Am Your Actual Quality, in the series Radio Lives.

Even so, the interview, which was conducted by the BBC producer Simon Elmes, proved to be of the greatest possible interest, both as a portrait of the otherwise unknown Pat and as an evocation of the Williams family’s home life. By some mischance the BBC Sound Archive had lost their copy of this unique testimony, but I was relieved to find that my own archive had retained it, and I have since taken the opportunity to restore to the Archive’s shelves one of the more amazing voices to be found there. Pat Williams was already enduring her final illness when she gave her interview, and several others who recorded their impressions at that time have also left us: Isabel Dean, Betty Marsden, Derek Nimmo, Dennis Main Wilson, Barry Took and Eric Merriman. Only fragments of their testimony appeared in the original programme, and I am grateful to the BBC for allowing them to speak now at length, if only on the printed page. A brief outline of their careers and preoccupations is given in the ‘Cast of Characters’ listing.

Kenneth Williams kept his memorabilia neatly filed and classified. Had he put together his own scrapbook of his life, much of it would have looked very like the book you are holding. Taken together with the sound of his voice, which is still so readily and multifariously available, these pages bring him as nearly back to life as we can manage. We hope he would have understood our desire – even need – to do so.