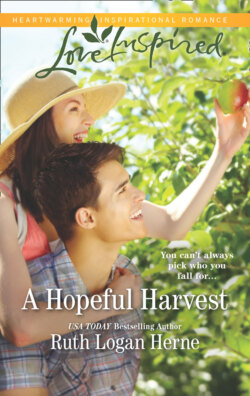

Читать книгу A Hopeful Harvest - Ruth Logan Herne - Страница 16

Chapter Four

Оглавление“The town won’t approve a building permit to replace the barn until they have a plan in front of them,” Jax told her the next morning. He tipped his army cap to block the angle of the morning sun as they waited for CeeCee’s bus. “I didn’t know what you had in mind, because there are several ways to go. We should sit down and talk about it. Get a plan drawn up.”

Should she? Libby wondered as CeeCee’s bus pulled to a stop in front of them. She kissed CeeCee goodbye and waved until the bus was up the road while she considered the question.

Did it make sense to rebuild the barn if she was going to sell the orchard?

It didn’t. Yet it felt wrong not to, as if she was shrugging off part of her family’s past. It couldn’t be built in time for the current harvest, so what was the point? “I need to really think about this,” she told him. “There are multiple issues and we’re in a time crunch. I’m in danger of having the Galas overripen, and no place to put them. I asked the Bakers if they wanted to buy them wholesale and market them with theirs, but it’s a bumper crop year and they’re overloaded. Who would ever think a great harvest was a bad thing?”

“A bumper crop year is perfect for cider production,” he noted.

“Gramps was the only one who could get the press to work,” she told him. “And the press was in the small barn that no longer exists. When I was a little girl they would buy tons of apples from the other farms to make cider. It was amazing to see. Now most of the apples are produced by the major fruit producers and Gramps stopped pressing cider when it became too difficult to find enough affordable apples. Did you know that our state exports over thirty percent of the apple crop now?”

He hesitated momentarily. “That bothers you?”

She answered as she moved toward the house. “No. It’s smart marketing. There’s only so much that can be used in one area or even one country. While that drives up the retail prices, it doesn’t have the same effect on wholesale prices. People expect us to be lower priced without the middleman but it’s a narrow profit margin.”

Jax didn’t hide his surprise quickly enough and she frowned. “You didn’t think I knew about margins and break-even levels and median production, did you?”

He made a face. “Busted.”

“I have a bachelor’s degree in supply-side logistics and merchandising, but when I got my degree I realized that I didn’t care as much about shuffling goods as I did about the presentation of goods. The final package. But one feeds the other, I guess.”

“The producer cares about one and the retailer rules the other.”

“Exactly.” She paused by the door and faced the now-empty barn site before addressing him again. “I want to take a couple of days to figure things out. About the barns, the rebuilding, the deductibles, what makes sense in the long run. I’m not fooling myself about Gramps’s condition.” She lifted her gaze to his. “I don’t know if it makes sense to put all that money into this property and then walk away. And if I don’t do it, I’m putting another nail in the farm’s coffin by inaction, which will limit my choices even further.”

He started to speak but paused when she held up a hand. “Give me three days. I’ll pray. I’ll sound it out with a few others around town and gather some advice. I’m always better when I have the facts surrounding me.”

“Fair enough.” He motioned toward the orchard. “I’ve got some bins being dropped off. We’ll get the early apples off the trees this week. I rented some cold storage space just outside town.”

She frowned. “That’s pricey.”

“The insurance had a clause for rental facilities as needed. It wasn’t a generous amount, but it will cover a couple of weeks. Enough to buy you a little time.”

He’d seen a need and developed a plan, which made him seem even more ideal because he’d not only saved her time, he might have saved the early apples. “That’s perfect.”

He was carrying a laptop bag over his shoulder. He motioned to it. “Can I take a spot on the back porch and run some figures? If you have Wi-Fi, that is.”

“We do and yes. Unless you’d be more comfortable inside?”

He headed for the shaded porch. “Too nice a day. When I was a kid, a day like this was called Washington Perfect. It got to be a saying with my brothers when something went right. We’d look at each other and say, ‘Washington Perfect.’”

“How many brothers do you have?” she asked, but the moment she did, he went quiet. Then he answered normally.

“Two. One older, one younger.”

She was going to ask if they lived locally, but he was already rounding the corner of the house. Just as well. She didn’t need to know personal stuff about him. Nor him about her. She was okay keeping her marriage to Keith to herself.

You’re afraid he’ll think you were stupid.

She swallowed hard as she climbed the short flight of stairs to the kitchen.

Every time she looked back on the past seven years, she felt stupid. A four-year college degree that she’d barely used, a horrific mistake in her choice of husbands and letting things go long enough to end up homeless. A smart woman would never put an innocent child in those conditions.

“There’s my girl!” Joy heightened Gramps’s voice when he saw her come through the door. “Come to visit, have you? I’ll get Mother. We can set a spell. Okay?”

She couldn’t squash his hope and re-explain their circumstances, how she was living with him and that he had a great-granddaughter he recognized some days and not others. “I’d like that, but first I’m going to take care of these dishes, okay?”

“She left them to sit there?” He stared into the kitchen, frowning, because Grandma had always taken pride in a clean kitchen and a job well-done. Libby saw the moment realization hit him. His face dimmed. His eyes lost their sparkle. He didn’t say a word. He simply shuffled away to his chair in the front room. He sat and studied the room around him, his eyes darting from this to that.

He was trying to memorize it, she realized.

He was studying things to commit them to memory. Within minutes he would forget again, and these brief moments when he tried to regain a hold on reality hurt the most.

Oblivion came with an air of peace. Realization brought nothing but frustration to a beloved man, but how could she justify hoping for oblivion when he was striving to maintain what little mental capacity remained?

“Keep things as structured and as much the same as you can,” the doctor had advised, and she’d been trying to do that, but life had been messing that up lately.

A soft tune came through the open window. Jax whistling “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree” like he’d done the other day.

Gramps’s song.

She took a glass of tea in to Gramps. He greeted her as if she was a waitress in a diner, and when he was settled, she decided she didn’t need anyone’s advice about the barn.

She was savvy enough to know that easing an old man’s last months was worth the cost of a mortgage to pay the balance on the barn. With land prices at record-high levels, she should recoup the investment when she sold the farm eventually. She’d stop by the local bank and get things in motion. They’d want a plan, too, most likely.

She used the back door to access the small porch facing northwest. Jax looked up immediately. The warmth in his expression made her heart stutter again.

She reined in her reaction, then indicated the sloping hills and rugged Cascades beyond them. The arid mountains were brown and bare in spots, a stunning difference to the lush valley below. “We don’t do much sitting out here during the cold months.”

“Or the front porch, either, I expect, if we get a whip wind.”

“And yet we get enough pleasant weather to make a porch seem like something to come home to, don’t we?” She crossed to the open post, gazed out, then turned her attention back to him. “I know I said I’d wait, but I decided I want to replace the barn. How do we pick plans to present to the board? Do I need to hire an architect?”

He motioned her closer. “I was just looking at some pole barn packages. You can go old-school with lumber and we can build a wooden barn, but the new pole barns are beautiful and cost-efficient.” He’d pulled up a web page of an appealing barn with overhangs on two sides. “I thought the porch covers would be good for outdoor displays. Protection from sun and rain. This model is lower and tighter with no wasted space and you could have a cooler big enough for the small forklift to bring bins in and out.”

“It’s beautiful.”

He nodded. “They’ve come a long way with these. You could go bigger, but I don’t think you need to. Room to store things in the back, room for a produce-type store up front and plenty of refrigerated space.”

“How do we get plans and how do we present them to the building inspector?”

“The plans are as easy as pressing a button,” he told her. “Do you have a printer?”

“In the front room, yes.”

“Wi-Fi enabled?”

She rolled her eyes. “It’s supposed to be but isn’t, so I keep a cable attached.”

He stood, laptop in hand. “Let’s print this up and get the ball rolling.”

She stepped back.

He didn’t want her to, because having her look over his shoulder—her long hair brushing his cheek as she leaned closer to check out the barn’s stats—was too good to resist.

He was drawn to her. No denying that.

Her pretty hair smelled of apples and spice. Did she do that purposely, because of the season? Or did she just like the shampoo?

He wanted to know that and so much more, which meant he needed to put the brakes on. Steer clear. Trouble was, he didn’t want to. Just as he was thinking those dangerous thoughts, three cars rolled into the driveway. An unlikely looking crew of people piled out. Gert Johnson spotted them and came forward the way she always moved when she wasn’t driving a bus. Quickly. “We’re here to help, Libby.” She motioned to the six local bus drivers gathering around her. “You point us in the right direction and we’ll get things going because when Gert Johnson says she’ll do somethin’, she does it, and the same goes for this motley crew.”

“I’ll find the printer,” he told Libby once he greeted the newcomers. “Then I’ll take folks into the orchard and we’ll get going on those Galas. How long have you got?” he asked the group, and Slim Viney spoke up first.

“We’ve got afternoon bus runs at two forty, so we have to leave here by two fifteen to get back in time. And we’ll be doing this every day until the job’s done. That’s what folks do in Golden Grove.” He aimed a significant look in Libby’s direction. “They shore each other up when the chips are down.”

“Sure do!” said Dora Donaldson, a stout but lively woman who helped run the church calendar for Golden Grove’s oldest church. Her great-grandfather had been one of the first settlers this side of Quincy, and he’d worked side by side with Jax’s great-grandfather a long time ago. Jax used his middle name as a surname here. If he uttered the name Ingerson, his relationship to CVF would be instantly known. Loved by some, hated by a few, his family had invested time and money to grow their business over four generations. He wasn’t one bit ashamed of that. He simply wanted to fly under the radar for a while.

His conscience scoffed as he went inside to hook up his laptop.

Three years and counting. That’s a long penance by anyone’s standards.

Would it ever be long enough when four of his men drew a death sentence that day? A dull throbbing began to take root at his temples. A throbbing that could explode into a massive headache.

Sit. Breathe. Do the relaxation techniques you’ve been taught. You can interrupt this cycle.

But he had no time to sit and do the breathing exercises to relax the muscles that clenched when memories came flooding back. He needed to get the barn plans printed and get into that orchard. He’d offered his help. Painful head or not, he’d made a promise. Now he had to keep it.

He frowned, crossed to the slim desk in the narrow hallway, hooked the laptop to the printer, printed a double set of plans, then checked on Cleve.

The old man had dozed off in his chair. His food was untouched. Jax debated leaving it there or taking it back to the kitchen. In the end, he left it. Cleve might eat when he woke up or might forget to eat at all, another disease conundrum. He started to head out, but a group of photos on the nearby wall caught his eye. He moved closer.

A middle-aged couple snuggled a little girl who looked a lot like CeeCee. Bright blue eyes laughed into the camera while a younger Cleve’s salt-and-pepper hair lay against the little girl’s golden curls. His wife seemed amused and delighted by something. Their antics, maybe? And this picture was flanked by a half-dozen other pics of Libby at various ages. The grandparents’ love for her was obvious. He also noted a conspicuous lack of parents in the photos.

“Them were good times for the most part.”

Cleve’s voice startled him.

The printer clicked off right then, too.

The old fellow looked that way, frowned and lifted his plate of food. “Mother never lets me eat out here, she must be gettin’ daft in her old age.” He giggled as if he was getting away with something and began taking small bites of food. “She said, ‘Cleveland O’Laughlin, we’ve got a child to raise and we need to set a good example.’”

“She meant Libby, I expect?”

The old man frowned. “Who?”

Jax saw no sense in riling the old fellow up so he changed the subject. “How’s your breakfast?”

“Good enough. Could use more salt.”

Libby came in just then, Gert came along with her. When she spotted Libby’s grandfather, she crossed the room and gave the old fellow a quick hug. “Cleve, it’s me, Gert Johnson. I live over on East Third Street, remember?”

“I don’t remember much, but I do recall that pretty face and a white wedding gown when you and B.J. Johnson got married a ways back.”

“Do tell.” She crouched low and smiled at him. “That was a fine wedding, wasn’t it?”

“It was.” He nodded, then tried to angle a bite of scrambled egg onto a piece of toast. One hand missed the other and the egg fell with a light plop onto the plate. “I was just tellin’ Mother that we haven’t seen you folks in a while. Got any kids yet?”

Libby started to interrupt, but Gert rose to the challenge nicely. “Four, and they are my pride and joy. I’m just stoppin’ in with some of my bus drivin’ friends to do some apple pickin’ for you, so if you see any of us wanderin’ round, we’re supposed to be here. Okay?”

“It’s picking time?” He peered toward the window as if checking the leaves and the weather for confirmation.

“It sure is,” she told him, “and we’ve got the best crew on board to help Libby while you folks put things to rights.”

“Libby.” He frowned, stared at Gert, then Jax and then Libby. “I don’t know a Libby. My wife’s name is Carolyn. She’ll be out here soon, I expect, especially when she sees me eating in the living room.”

Unremembered. Unappreciated. Misunderstood.

Jax remembered the drill like it was yesterday, not a dozen years before. How his brothers shied away from Grandma Molly’s sharp tongue and wild ramblings because it hurt to be forgotten. It hurt to be overlooked by someone who loved you enough to raise you to be fine young men. He looked at Libby.

She’d wiped the frown from her face and moved forward. “I think Grandma would approve. She gave me her permission to let you eat out here when CeeCee and I moved in last year. She wanted you happy and healthy, Gramps.”

He frowned, then slapped a hand to the chair arm. “Oh, Libby! Yep, I recall a Libby now, a little girl, real pretty curls and we had to straighten her teeth. Cost a fair penny, too, but in for a penny, in for a pound, I like to say.”

“And very pretty teeth they are,” quipped Jax. He smiled at Libby to ease the moment, then raised the sheaf of papers in his hand. “I’m going to put a set of these in the truck, then I’ll take the pickers into the orchard. We’ll start filling sacks and bins. I saw a pile of apple sacks on the back porch.” Apple sacks were strong canvas bags draped around the neck, leaving both hands free to pick fruit.

“I washed the dust out of them over the weekend, so they were spared the onslaught of the wind,” Libby told him. “There’s about fifteen there. Take what you need.”

“Will do.” He reached over and touched Cleve on the shoulder. “I’ll be picking apples today, too. If you want to take a walk or give us a hand with the Galas, I’d be happy to have you by my side.”

“I’m fast,” Cleve warned him, and he puffed up his chest when he said it. “Folks couldn’t believe how fast I was when it came to apples, but I don’t let anything keep me down. Persistence runs in my family, you know.”

“I’m sure it does.” Jax stepped back.

Libby took Cleve’s empty plate and moved back, too.

She didn’t look pained by the old man’s pendulum swings of behavior and memory. She took the plate to the kitchen quietly, then rinsed it under a stream of water. He followed to use the side door but paused when he noticed three new crayon drawings of doglike creatures on the refrigerator. “CeeCee’s been planning her campaign, I see.”

“Oh, she has.” Libby sent the new dog images a bemused look. “She wants a dog in the worst way, so her renditions of Dreamer keep appearing throughout the house. There was even one on the upstairs bathroom mirror this morning.”

“I hear persistence runs in the family,” he teased.

“And then some,” Libby replied. “But I can barely stay afloat with what I’ve got going now. How do I add a dog into the mix?” She shrugged. “Maybe next year. I need to know where I’ll be before I can commit to something that’s going to be around for a dozen years or more. Do you have a dog?” she asked. For some reason, the question caught him off guard. He almost stuttered his reply.

“I did. Now I don’t.”

She noticed the pain in his voice. He saw the recognition in her face. “It’s hard to say goodbye, isn’t it?”

He’d never gotten a chance to say goodbye. Flint had died four weeks before he’d come home, killed by a hit-and-run driver.

His friends gone because of a mechanical mistake.

His dog gone when a careless driver had left him lying in a ditch along Route 2. He walked toward the back door. “I’m going to stow these, put my laptop away, then get to work.” Thoughts of Flint and the war put a vise grip on his temples.

He stowed the computer and the barn plans, grabbed a stack of bags and gave one to each bus driver. While the earnest pickers began bringing in what might be Cleve O’Laughlin’s final harvest, he piled apple crates onto his truck, then unloaded them in strategic locations along the straight, trimmed rows of the old-style orchard.

He’d made it through these last few years by keeping busy, holding thoughts at bay. As long as he was moving, he could make it through the days because if he stayed busy enough, there wasn’t time to consider the problems that plagued him at night.

The doctor had prescribed sleeping pills.

Jax refused to take them because being kept asleep artificially was almost as scary as being unable to sleep. What if the meds never wore off and he just stayed asleep forever?

He shoved the thoughts aside, dropped off the crates, then joined the pickers, doing a job he’d been raised to do from the time he could walk. To pick Washington Perfect apples, like everyone in his family before him. For today it would be enough if the pain would just stop.