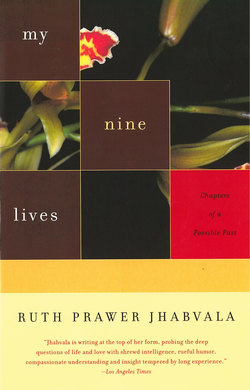

Читать книгу My Nine Lives - Ruth Prawer Jhabvala - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Ménage

LEONORA WAS my mother, Kitty my aunt. Kitty had no children, she never married because Yakuv didn’t believe in marriage, and once she met him, she never looked at anyone else. “He treats her like dirt,” my mother used to say, the corners of her mouth turned down—an expression I knew well, for it was often how she regarded me while telling me, “You’ll end up like Kitty: a neurasthenic.” Physically, it would have been impossible for me to become either like my mother or my aunt. They were both tall, statuesque, whereas I have taken after my father who was a lot shorter than my mother. It’s odd that both these sisters chose men who were short—though this was all that Yakuv and my father Rudy had in common.

Leonora dominated Rudy and he liked it. She was a wonderful manager of all practical details, but at that time I resented and perhaps rather despised her orderly bourgeois ways. I often took refuge with Kitty, who lived in three tiny rooms in a subdivided old brownstone. My parents had a large apartment in an expensive building on Central Park West, filled with some very fine furniture and pictures that had belonged to Rudy’s family of prosperous Berlin publishers. Unlike Rudy and Leonora, who had funneled out his family money through Switzerland, Kitty had arrived here in 1937 with nothing—except of course my parents, who were a constant support to her.

Kitty’s apartment was always in a mess, which for me was part of its charm. I associated disorder with artistic creation, and there was usually some piece of work lying around. She had begun with etchings and woodcuts but later became a photographer; there were prints tacked up of her charming portraits of little girls picking flowers in a meadow. Kitty herself sat on the floor, her arms wrapping her knees and her long reddish hair trailing around her. If my mother was there—and Leonora often came to check up on her sister—she would be tidying panties off the floor, washing the dishes piled in the sink, while clicking her tongue in distress and disapproval. But that didn’t bother Kitty at all, she continued sitting there talking to me about some artistic matter, even when Leonora found a broom and began to sweep around her.

My parents adored New York, were completely at home here, and continued to live the way they might have done if they had been allowed to stay in Berlin. They spoke only in English, though their heavy accents made it sound not unlike their native German. They had many social and cultural activities, mostly with other prosperous émigrés from various Central European countries. It was at one of these cultural events that Kitty first met Yakuv, who had been engaged to give a piano recital after a buffet supper at some rich person’s house. The house was pointed out to me later, a rococo mansion at 90th and 5th, since pulled down. At this concert Kitty had behaved in a crazy way that was not uncharacteristic of her: the moment Yakuv had finished playing, she dashed up to the piano and, kneeling down, she kissed his hand. Leonora said she nearly died of shame, but Rudy was more tolerant of his sister-in-law’s behavior, which he said was a tribute not to a person but to his art. As for Yakuv himself—I don’t know how he took her gesture, but probably it was in his usual sardonic way.

On account of his art, my mother was prepared to forgive Yakuv for many things: among them, his background. He came from Eastern Europe, from what she assumed to be a tribe of pedlars and hawkers; the language they spoke was to her a debasement of the High German with which she had grown up. But this had nothing to do with Yakuv’s art: “Even if his father peddled toilet brushes,” she explained, “an artist is born with his talent. It’s a gift from the gods and comes from above.” His real background might have disturbed her more. His forefathers had been rabbinic scholars, but more recent generations had abandoned these studies in favor of Marx and Engels, Bakunin and Kropotkin. Some of them had rotted for years in jail as political prisoners, and at the beginning of the last century an aunt had been executed for her part in an unsuccessful assassination attempt. The glowering intensity that pervaded Yakuv’s music, and our lives, must have been inherited from these revolutionaries. His looks were as fiery as his playing. He was very short but with broad shoulders and an exceptionally large head, which looked even larger because of his shock of black curly hair.

A year or two after his first meeting with her, Yakuv moved into the brownstone where Kitty lived. His rooms on the top floor were even smaller than hers on the second and just as untidy. But I have seen Yakuv get much angrier than my mother at the mess in Kitty’s rooms, kicking things around the floor in a fury and sweeping crockery off her table. Then she would fly at him, and a dreadful quarrel break out. These were the first passionate fights I ever witnessed, for between my parents there was only a slight tightening of the lips to indicate one of their rare differences of opinion. Kitty’s fights with Yakuv frightened and thrilled me by their violence. They always ended the same way, with Yakuv going upstairs to his own den as though nothing had happened—he might even have been smiling—while she was left quivering, prostrate on the floor. But soon she would get up and rush to the door to scream up the stairs—uselessly, for by that time he was back at the piano and she could not be heard above his playing.

At the time we first knew him, in the early 1940s, there was a surfeit of talented refugee pianists, so Yakuv had to struggle to make ends meet. He played for a ballet class and gave piano lessons to untalented students, of whom I became one. At six, my eager parents had sent me for piano lessons to a little old Russian lady, who spent most of her time with me writing appeals for visas to consular officials. But when I was twelve, my parents decided that I should take lessons from Yakuv. I was very reluctant, for I had often seen his pupils coming down from their lessons in tears. I knew this would be my fate too—and deservedly, for he was a great musician and I had very little talent. He made no attempt to disguise his despair, putting his hands over his ears and imploring to be struck deaf. He begged me never to come back again, never to think of the piano again, and of course I would have liked nothing better; but however much we swore an eternal farewell when I left, I always returned on time for my next lesson. I knew—we all knew, including himself—that he needed the money, and since he had driven most other pupils away, it seemed up to me to stick it out, however painful this might be for both of us.

And actually, apart from my playing, I liked being with him. He had three little rooms, and the one in which he gave lessons was only just big enough to hold his piano. The window faced the back yard which was wild and overgrown since the first-floor tenant had no money to keep it up. At that time the mammoth apartment buildings had not yet been built, so the house was surrounded by other brownstones with similarly untended gardens and trees growing tall enough to fill his window. Yakuv, in a shabby jacket and rimless glasses, filled the room with smoke from his little black cigars. A cup of coffee stood on the piano, and since I never saw him make a new one, it must have been stone cold; but he kept sipping at it, and dipping a doughnut into it. Although coffee, doughnuts, and cigars appeared to be all he lived on, he was full of energy. He roared, stamped, heaped me with his sarcasms. Sometimes I got so mad, I banged down the piano lid, and that always seemed to amuse him: “I see you have inherited your aunt’s sweet temper.” But then he pinched my cheek, almost with affection, and walked me out the door with his arm around my shoulders.

I was not the only one in the family to take lessons from him. I don’t know whether my father did this because he really wanted to learn or to contribute to Yakuv’s income. He came not to play the piano but to sing Lieder; he loved music but was unfortunately as unmusical as I am. I have heard Yakuv tell Kitty that the entire neighborhood was trilling Die Schöne Müllerin while my father was still struggling with the first bars. Poor Rudy—he must have endured the same sarcasms as I did, but all he would say was that Yakuv had the typical artistic temperament. Then Kitty said: “So artistic temperament gives one the right to be a swine?” She spoke bitterly because he fought with her, wouldn’t marry her, wouldn’t let her have a child with him. This last always came up in their quarrels: “All right, so don’t marry, leave it, forget it—but a child, why not a child!” He wouldn’t hear of it; and it really was impossible to think of him as a father, a gentle comforting presence like Rudy.

Yet he and Kitty had their tender moments together. Sometimes on my visits to her I found them in bed together. They were not at all shy but invited me to sit on the side of the bed. We played games of scissors, paper, stone, with the two of them quickly changing to scissors if they saw the other being paper; or he would teach us card games and didn’t contradict when she told me that he could have made a living as a card sharper. “Better than the piano,” he said cheerfully. Without his glasses, he looked almost gentle, probably because he was so nearsighted; and it was always a surprise to see that his eyes were not dark but light grey.

Then there were the times when he was a guest at one of my parents’ dinner parties. On those evenings Leonora sparkled in a low-cut evening gown and the sapphire and ruby necklace she had inherited from her mother-in-law. Her successful dinners were her personal triumph, so that she was entitled to the little glow that made two red patches of excitement appear on her cheeks. But at that time, when I was about fifteen or sixteen, I was embarrassed by what I thought of as her smug materialism. It seemed to me that she cared only for appearances, for her silver, her crystal and china, and for nice behavior (she even tried to make me curtsey when I greeted her guests). She was in her middle thirties, in wonderful shape, radiant with health and the exercise and massage she regularly took: but I thought of her as sunk in hopeless middle age with no ideals left, if ever she had any, which I doubted.

Except for me, everyone appreciated her dinner parties, including Yakuv whenever he was invited. In his crumpled, rumpled evening suit, he ate and drank like a person who is really hungry: which he probably was, and certainly Leonora’s exquisite dishes must have been a wonderful change from his stale coffee and doughnuts. After dinner he was persuaded to sit down at the piano, and this my parents made out to be a special favor to them, though before he left Rudy’s check had been tactfully slipped into his pocket. He played the way he ate—voraciously, flinging himself all over the keys, swaying, even singing under his breath and sometimes cursing in Polish. All this made him perspire profusely, so that afterward he could hardly respond to the applause because he was so busy wiping his face and the back of his neck. The enthusiasm was genuine—even unmusical people realized that they were in the presence of a true artist; and I could well imagine how Kitty had been so carried away the first time she heard him that she knelt at his feet.

Kitty resented the fact that Yakuv performed for my parents’ guests, that he had to do so in order to earn money; and also that he himself didn’t resent it enough. He never complained, as she did constantly, about his lack of reputation and success. He probably didn’t think it worth complaining about. A bitter sardonic person by nature, he expected nothing better from fate, which he accepted as being terrible for everyone. When Kitty tried to make him say that he only went to Leonora’s parties because of Rudy’s check, he said, “Oh no, I go for the food—where else would I get veal in a cream sauce like Leonora’s?” And never losing an opportunity to provoke her, he added, “If only you learned to cook—just a few little dishes, one isn’t even expecting miracles—”

“Oh yes, now you want me to be your cook-housekeeper! How you would hate it, hate it!”

He laughed and said that on the contrary, a cook-housekeeper was just what he needed; but we both knew that he didn’t mean it because the three of us were on the same side—what I thought of as the artistic, the anti-bourgeois side.

This was the way things stood with us when I went away to college and then, two years later, on my own quest—which I won’t go into now except to say that I may have been influenced by Yakuv’s view of life. I mean by his pessimism, his assumption that no hopes were ever fulfilled in this life; and while he left it at that, it may have been the reason why I, and others like myself, Jewish and secular, turned to Buddhism. For a while I wanted to be a Buddhist nun—it seemed a practical way out of the impasse of human life. But then I dropped the idea and got married instead.

With all this happening, I became detached from my family in New York. I skimmed through their letters only to satisfy myself that everything was as it always had been with them. It was difficult to tell my parents’ letters apart: they had the same handwriting with traces of the spiky Germanic script in which they had first learned to write. The facts they presented were also the same—the concerts and plays they had liked or disliked, an additional maid to help Lina who had got old and suffered with her knees. Kitty in her scrawl did not report facts: only excitement at a painting or a flowering tree, anguished longing for a child, Yakuv’s impossible behavior. He of course did not write to me. I don’t suppose he wrote any letters; to whom would he write? Apart from our family, he seemed to have no personal connection with anyone.

The only change they reported was that the brownstone in which Kitty and Yakuv had been renting was torn down. That whole midtown area was being built up with apartment blocks where only people with substantial incomes could afford to live. Kitty gave me a new address, downtown and in a part of the city that had once been commercial but had been moribund for years. When I went to see her on my return to New York, I found the warehouses and workshops still boarded up; the streets were deserted except for a few bundled-up figures hurrying along close to the walls. This made them look like conspirators, though they may only have been sheltering against the wind, which was blowing shreds of paper and other rubbish out of neglected trash cans. But some of the disused warehouses were in process of being revived, one floor at a time. In Kitty’s building there were two such conversions, and to get to hers I had to operate the pulleys of an elevator designed for crates and other large objects. Kitty’s loft, as she called it, seemed too large for domestic living though it had a makeshift kitchen with a sink and an old gas stove. Kitty’s own few pieces of furniture looked forlorn in all this space; even Yakuv’s piano—for his furniture too had come adrift here—seemed to be bobbing around as on an empty sea. He himself wasn’t there; he was on tour, things were better for him now and he was getting engagements around the country. And Kitty’s career also seemed to have taken off: she had rigged up a dark room in one corner of her space, and in the middle of the floor was a platform with two tree-stumps on it, surrounded by arc-lights and a camera on a tripod.

Instead of going to my parents, I had come straight to her from the airport. I felt it would be easier to tell her about what I saw as the dead end of my youthful life—I had abandoned both my Buddhist studies and my marriage—and it was a relief to unburden myself to her. She listened to me in silence, which was really quite uncharacteristic of her. There were other changes: the floor had been swept, there were no dishes in the sink. After I had finished telling her whatever I had to tell, she murmured to me and stroked my hair. How right I had been to come to her first, I felt; I knew I could not expect the same understanding from my parents, whose lives had been so calm, stable, and fulfilled.

My parents’ building and all its neighbors stood the way they had through all the past decades, as stately as the mansions that they had themselves displaced. The doormen were the same I had known throughout my childhood; so was the elevator man who took me up to where Leonora was waiting for me in the doorway. She held me to her bosom where I remembered to avoid the sharp edges of her diamond brooch. “But now it’s my turn!” Rudy clamored, caring nothing about having his good suit crumpled as I pressed myself against him, inhaling his after-shave and breath-freshener.

But “No not here, darling,” Leonora said when I started to go into my room. My father cleared his throat—always a sign of embarrassment with him. But Leonora exuded a triumphant confidence: “Because of the piano,” she said, ushering me into the guest bedroom, which was considerably smaller than mine. I didn’t understand her: the piano had always been in the drawing room and was still there. “The other piano,” she said. “His.” She spoke as if we had already had a long conversation on the subject. But we had not, and it took me some time to realize that this other piano was Yakuv’s new one that Rudy had bought for him.

Again skipping intermediate explanations—“It’s so noisy at Kitty’s,” Leonora said. “Could someone tell me why she has to live in a warehouse? He needs peace and quiet; naturally—an artist.”

So there had been changes, and principally, I noticed, in Leonora. Her coiled hair was newly touched with blonde; her cheeks had those two spots of excitement I knew from her dinner parties. She kept taking deep breaths as if to contain some elation inside her.

Rudy took me for a walk in Central Park. As usual on his walks, my father wore a three-piece herringbone suit, a Homburg hat, and carried a rolled umbrella like an Englishman. From time to time he pointed this umbrella in the direction of a tree, an ornamental bridge, ducks on a pond: “Beautiful,” he breathed, loving Nature in its formal aspect. Around us towered the hotels and apartment blocks of Central Park South and West, which he also loved—for the same decorative solidity that had formed the background of his Berlin youth and his courtship of my mother.

“It’s a privilege for us to give him what he has never had. A quiet orderly home, meals on time—yes yes, this sounds very—what do you call it? Stuffy? Square? But even artists,” he smiled, “have to eat and sleep.”

“What about Kitty?” I said.

“Kitty. Exactly. They’re too much alike, you see; artistic temperaments. Sometimes he needs—they both need—a rest from the storm and stress. Nothing has changed. Leonora and I are what we have always been.”

“Mother looks wonderful.”

“You know how she has always adored music above everything.” Then he exclaimed: “Dear heaven, who says we’re not sensible grown-up people! We’ve learned how to behave. You’re still a child, lambkin.” He squeezed my arm, in token of my misery and failure. “One day you too will learn that everything turns out the way it has to, for good; for our good.” He pointed his umbrella—at the sky this time, inviting me to look upward with him toward the immense perfection that was always with us, encompassing our small mismanaged lives.

A week or two after my arrival, Yakuv returned from his tour. He had not changed. He at once went into what used to be my bedroom—without apology, probably he didn’t realize that it had been mine, or simply took it for granted that it was now his. He greeted me with a comradely clap on the shoulder, not as if I had been away for several years but as if I had showed up as usual for my weekly lesson. Leonora followed him into the room; she had to unpack his bag, she said, because if she didn’t it would stand there for weeks. But this was said with a smile, not in the reproachful way she used for Kitty’s and my untidiness. After a while, during which Rudy went for another of his walks, she emerged with an armful of Yakuv’s laundry. Soon came the sound of his piano, and every day after that it seemed to fill, to appropriate the apartment. If I moved around or shut a door a little too loudly, she or Rudy, or both, laid a finger on their lips.

Leonora did everything possible to create the best conditions for his work. She arranged his schedule with his agent, whom he often fired so that she had to find a new one; and since it infuriated him to have anyone disarrange his music sheets, she cleaned his room herself. Otherwise he was calm, immersed in his work. He rarely asked for anything and good-naturedly accepted even what he didn’t want—Leonora once gave him a dark blue velvet smoking jacket, and though he mildly protested (“So now I must look like a monkey”), he let her coax him into it. He also smoked the better brand of cigars she bought him to replace the little black ones he was used to. He had personal habits but was not entrenched in them, and if it made no difference to him, he gladly obliged her in everything.

That was during the day. But during the evening meal, he would push his plate back and without waiting for the rest of us to finish—he still ate in the same rapid, ravenous way—he went out, banging the front door behind him. He never said that he was going, or where; he was not expected to, and anyway, we knew. But there were times when he did not return for several days, and while I had no idea what transpired between him and Kitty during those days, I was very much aware of the effect his absence had on Leonora. She behaved like a sick person. She stayed in her bedroom with the curtains drawn, and “Leave me alone,” was all she ever said to Rudy’s and my efforts to rally her. It was not until Yakuv returned that she got up, bathed and dressed and tried to return to her normal self. But this was not possible for her; she appeared to have suffered a collapse—even physically she had lost weight and her splendid breasts sagged within her large bra. I don’t think Yakuv noticed any of this; anyway, it did not affect him since in his presence she made a brave attempt to pull herself together and go about her household duties as usual, especially her duties to him. She would not have known how to stage the sort of confrontations that he was used to with Kitty; and since these were lacking, he probably assumed that everything was fine with Leonora—that is, insofar as he thought of her at all.

Rudy wanted to take her on a Mediterranean cruise. A few years earlier they had enjoyed sailing around the Greek Islands, but now Leonora was reluctant to leave. She said she couldn’t; Lina was too old and cranky to look after the house properly, everything would be topsy-turvy. I could hear my parents arguing in their bedroom at night, Rudy as usual calm and reasonable, but she not at all her usual self. In the mornings Rudy would emerge alone from their bedroom, and he and I would discuss ways of persuading her. We laid stress on her health—“Look at you,” I said, making her stand before her bedroom mirror.

She drew her hand down her cheek: “You think I look terrible?”

“You’ll see how well you’ll look after a change—young all over again. Young and beautiful.”

“Really?” She continued dubiously to regard herself in the mirror.

It was only when I promised to take over all her responsibilities that she began to accept the idea of Rudy’s cruise. But first she had to train me in the arts that she herself had learned from her mother and grandmother; and it was only when she was satisfied that I knew how to take care of all Yakuv’s needs that she finally agreed to leave. Rudy was overjoyed; he whispered promises of another honeymoon. He packed their suitcases in his expert way but humbly unpacked them again when she, who also prided herself on her packing, pointed out how much better it could be done.

It was only when he saw these suitcases standing in the hall on the day before departure that Yakuv realized what was going on. His reaction was unexpected: he took the cigar out of his mouth and said, “Why didn’t anyone tell me?” When Leonora began to speak, he waved his hands and stalked off into his room. We waited for the piano to start up but nothing happened; only silence, disapproval seeped from that room and filled the apartment and Leonora’s heart so that she whispered, “We can’t go.”

I had never seen my father so angry. “But this is too much! Now we have reached the limit!” Leonora and I gazed in astonishment, but he went on, “Who is this man, what does he think?” Then—“Tomorrow he leaves! No today! Now! Hop!” He made straight for Yakuv’s door, and had already seized the handle when Leonora grasped his arm. They tussled—yes, my parents physically tussled with each other, a sight I never thought to see. She pleaded, he insisted, she used little endearments (in German) until he turned from the door. His thinning grey hair was ruffled, another unprecedented sight in my serene and serenely elegant father. In response to Leonora’s imploring looks, I joined in her pleas to postpone this expulsion, at least until they returned from their trip. “Our second honeymoon,” Leonora pleaded, until at last, still red and ruffled, he agreed.

But later that night he came to my room. He told me that by the time they returned from their cruise, Yakuv would have to be out, pronto, bag and baggage, and it was up to me to see that this was done. His mouth thin and determined—“Bag and baggage,” he repeated, and then, in another splutter of anger: “Ridiculous. Unheard of.”

They were to be away for six weeks and during that time I had to get Yakuv to pack up and leave. But he gave me no opportunity to talk to him. He stayed in his room, and all day the apartment resounded with music of storm and stress. Only sometimes he rushed out to walk in the Park; once I followed him, but there too it was impossible to talk to him. Hunched in an old black coat that was too long for him, he appeared sunk in his thoughts. His hands were in his pockets and he only took them out to gesticulate in furious argument with whatever was going on under his broad-brimmed hat.

I had to turn to Kitty for help. The change in Kitty was as marked as it was in Leonora, but in the opposite direction. It was Kitty who looked calm, and though no longer young, she now appeared younger than before. Instead of her long skirts and dangling loops of jewelry, she wore a flowered artist’s smock that made her look as wholesome as a kindergarten teacher. Her eyes had lost their inward brooding look and were clear and intent on the proof-sheets she was holding up to the light. She made me admire them with her—they were all of pretty little girls posed on her tree-stumps—and she only put them down when I told her of the task my father had imposed on me.

She laughed in surprise: “I thought Rudy was so proud of keeping his own little Paderewski.”

“He thinks Leonora is getting too nervous.”

Now she really laughed out loud: Leonora nervous! It was the word—together with neurasthenic, or later, neurotic—that had always been applied to Kitty herself.

“And Yakuv too,” I ventured.

She put down her proof-sheets: “Oh yes. He’s in one of his moods. The other night I was busy in my dark room and that made him so mad he stamped and roared and tore down the pictures I’d pinned up. He said he couldn’t stand the way I live. Well, nothing new—I’ve heard it a thousand times before . . . But Leonora? Are you telling me he misses Leonora?”

It was then that she offered to tell Yakuv to get out of our apartment. I was glad to be relieved of this task and to have time to go about my own business. After all, I still had a divorce to take care of, as well as deciding whether to go back to college or to find a job. And what about all those existential questions that had so troubled me? I needed to become involved again with my own concerns rather than those of my parents and my aunt. I decided that, as soon as Rudy and Leonora returned, I would look for a place of my own. Picking up some old connections and making new ones, I was out and about a lot and continued to see nothing of Yakuv. I’m afraid I neglected most of what Leonora had left me to do for him, but he didn’t complain and perhaps didn’t notice. Whenever I was home I heard him playing a lot of loud music. I assumed he was preparing for his next tour and hoped that he would have left on it before my parents returned. He showed no intention of moving out but presumably he would as soon as Kitty had talked to him. Meanwhile he continued to thump away behind his closed door; he seemed to be there all the time now, even at night.

Then late one evening Kitty herself showed up. It was pouring with rain, but it turned out she had walked all the way from downtown. When I tried to make her take off her wet clothes, she waved me away—her attention was only on the sounds from Yakuv’s room. “So he’s still here,” she said, partly in anger, partly in relief.

It may have been because she was so drenched, with her hair wild and dangling as it used to be (though dyed a more violent shade of red), that she had reverted to the Kitty I used to know. And her mood too was charged in the old way. She told me how she had tried to call Yakuv all day and every day, though she knew he hardly used the telephone and certainly never answered it. The last time she had seen him was when she had told him of Rudy’s ultimatum. Without a word and waving his hands in the air, he had rushed out of her loft and had not returned. She had begun to fear that he had packed up and left our apartment in offended pride, abandoning not only my parents but Kitty too. Tormented by this thought—that he had taken himself out of our lives for ever—she had come running through the dark and the rain: only to hear his piano as usual in the room he had been told to vacate.

Suddenly she rushed in there. I was surprised and apprehensive: even when they had still been living together in the brownstone, Kitty had rarely dared to enter his room while he was playing. If she did, there would be a fearful explosion, with objects flying down the stairs until Kitty herself came running down them, declaring, “He’s a madman, just a crazy, crazy person;” and Yakuv would appear at the top of the stairs, shouting the same thing about her. But now there was no explosion. The playing stopped abruptly. All I heard was her voice and nothing from him at all. I went to bed, expecting them to do the same. And why not? Two people who had been living together, on and off, for over twenty years.

Later that night they woke me up. They sat on either side of my bed; they appeared exhausted, not as after a fight but after long futile talk. It was almost dawn and it may have been the frail light that made them look drained.

“He claims he can’t live without her . . . He used to laugh at her!” She turned on him: “Now what’s happened? Because it’s you she cooks for now, all her potato dishes, is that what you can’t do without?”

He shook his head, helplessly. He didn’t have his glasses on and looked as I remembered seeing him in bed with Kitty: mild, melancholy, his grey eyes dim as the dawn light.

“My aunts always told me, ‘The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach.’ I thought they only meant people like my fat uncles. I didn’t know artists were included. If that’s what you are!” she cried. “You thump your piano loud enough: what’s all that about? Passion for food or for the housewife who cooks it?”

He remained silent—he who was always so flip, so quick with his sarcastic replies. He stretched across me to touch her: “Kitty,” he said, his voice as sad as his eyes.

“Let me be!” she cried, but obviously this was the last thing she wanted.

My parents returned two weeks earlier than expected. Their second honeymoon had not been a success. They had sailed through the classical world, and for him it had been an enchanted return to civilization: his civilization, of order, calm, and balance. But she, who had upheld this rule of life with him, had seen it crumble away. She wept, she suffered. He held her in his arms, which he couldn’t get entirely around her, she was so much larger than he. While promising nothing, he began to consider means of adjusting to their new situation.

It was amazing how well he managed to restore the harmony of our household. His relief at finding Yakuv still installed in the apartment was almost as great as hers. Her husband’s forbearance evoked Leonora’s gratitude—and maybe Yakuv’s too, though he probably took his own rights for granted. Soon Leonora was herself again. She sang as she moved around her furniture with the feather duster that was her scepter. Practical, punctual, perfect, her figure restored to full bloom, she dispensed food and comfort in return for the love of men.

Yakuv continued to practice behind his closed door, emerging only for meals. His music no longer stormed in rage but was as calm as could be expected of him. My father too was calm—that was his nature—but now with some hidden sorrow that made me postpone my plan of finding my own place. Sometimes I joined him on his walks, or we played chess, a game he loved though he always lost. That didn’t matter to him; he was a bad player but an excellent loser.

Kitty changed—or rather, changed back again. Instead of the simple flowered smock, she reverted to her flamboyant dresses, looped with large, noisy pieces of costume jewelry. Several times she came storming into the apartment, probably after walking all the way from downtown, as she had done on that rainy night, and as on that night, ready to burst into the room from where the piano rang out. But each time she was prevented by Leonora who stood in front of the door, her arms spread across it. Then Rudy intervened; he took his sister-in-law’s hand and spoke to her soothingly. Kitty let herself be led away meekly, saying only, “Do you know how long he hasn’t come to me?” Then I realized that Yakuv had been spending not only all his days but many of his nights in our apartment.

It might be thought that their rivalry would turn the sisters into enemies, but this was not at all what happened. Instead they drew closer together in an intimacy that excluded even Rudy and me. They met several times a week, not in our apartment where they could not be alone, nor in Kitty’s loft—Leonora refusing to venture into that part of town, which seemed wild, dark, and suspect to her. Their favorite rendezvous was the Palm Court of a large hotel, probably similar to the sort of place they had frequented in their youth, with gilt-framed mirrors, a string orchestra, and ladies and gentlemen (some of them lovers) seated on plush sofas enjoying their afternoon coffee and cake. Here Leonora and Kitty exchanged their intimate secrets, just as they had done when they were young. At that time Leonora had confided the tender ins and outs of Rudy’s courtship, Kitty had analyzed the characters of her lovers whom it had amused her to keep dangling on a string. Now the confidences they shared were about the same man. They would also have spoken—this was their style—of Life in general, of Love. Sometimes they may have glanced at their reflections in the hotel mirror, pleased at what they saw: though older now, they were still the same handsome sisters, Leonora in her elegant two-piece with the diamond brooch in the lapel, Kitty still bohemian under a pile of bright red hair.

A decade passed in this way within my family. Meanwhile, I came and went; I saw that the situation was not going to change in a hurry nor was there anything I could do about it. Rudy encouraged me to leave, even though I was the only one to whom he occasionally showed something of his own feelings instead of pretending he didn’t have any. I went back to college to finish my degree, I read a lot, I began to write. I had one or two stories published in little magazines, and these made my father so proud that he bought up copies to give to everyone he knew.

Yakuv also came and went. He was often on tour, for his reputation was now established and he had engagements all over the country. It did not improve his temper—on the contrary, he became more difficult. He was still firing his agents so that Leonora had to find new ones and also secretaries to attend him on his tours. Usually these secretaries returned without him; either he had fired them or they couldn’t stand him another day. He would cable urgently for a replacement, but by then everyone had heard about him and no one was willing to go. He blamed us for this failure—what could he do, he said, if we sent him nothing but blockheads and idiots, and meanwhile how was he to manage, again he had missed a plane and left the suitcase with his tails in a hotel? Twice Leonora went herself to take care of him, but when they came back, they were not on speaking terms and Rudy had to make peace between them. Leonora refused to undertake another tour with him; and after a barrage of urgent messages from Kansas City, Kitty was dispatched to him—with misgivings that turned out to be justified, for he sent her back within a week.

Sometimes I suspected that his tantrums were not entirely genuine. I have seen him turn away, suppressing a smile—exactly as he had done in earlier years after some wild fight with Kitty. The music we heard him play after one of these upheavals was invariably tranquil, romantic, filling everyone with good feelings. “With me, too, his manner had never changed from the time I was a child and he my teacher. He gave me books he thought I ought to read, and when he wanted to relax, he called me to play some game with him—dominoes usually, to my relief, never chess at which I suspected him to be a master. When he wanted to be affectionate, he still pinched my cheek; and when he was angry with me, it was not as with the others but as with a child, wagging his finger in my face. This made me laugh, and then he laughed too. Eventually it happened that when he was in one of his moods, Leonora and Kitty would send me to calm him down. It was as though I were free of the web that entangled them—by this I suppose I mean their intense sexual involvement with him. I felt nothing like that; how could I? For me he was just an elderly little man, almost a dwarf with a huge head and a mass of grey hair. His teeth were reduced to little stumps stained brown with tobacco.

When another crisis arose with another secretary fired in mid-tour, it was natural for someone—was it Leonora, was it Kitty?—to suggest that I should take my turn with the job at which they had already failed. It was my father who objected; he said he had higher expectations for me, and hoped I had for myself too, than to be handmaid and servant to Yakuv on his travels. Leonora and Kitty reared up as one person—it was strange how united they were nowadays; they said it would be a rich experience for me as well as a privilege to be in close contact with an artist like Yakuv. Rudy made a face as though saying—perhaps he actually did say—hadn’t we had enough of this privilege over the past ten years? But he gave me money for the trip and told me to wire for more when I needed it, especially if I needed it for my ticket home.

Almost the first thing Yakuv said to me was, “You’ll need some money.” This was in a cab on our way from the airport—unexpectedly, he had been standing there waiting for me. He put his hand in his pocket and drew out a fistful of notes: “Is this enough?” He put his hand in his other pocket and drew out some more. From then on it was the way we carried out all our financial transactions: he didn’t pay me a salary but just offered me everything in his pockets to pick out as much as I needed. This was not very much, since my hotel room and plane tickets and cab rides were all included in his, paid for by the sponsors. I lasted longer than anyone else had done, traveling with him from one city to another. We always checked into the same kind of hotel, I in a small single room and he in a suite that had often to be changed, due to his complaints about noise and other inconveniences. During the day, if I didn’t go to his rehearsals, I stayed in the hotel by myself; I wasn’t interested in the cities we were in—they were all the same, with the same sort of museums built in the early 1900s by local millionaires to house their art collections. At night I attended his performances in a concert hall donated by a later set of millionaires; I was very proud of him, his playing and the effect it had on his audience. He was not only a superb pianist, he looked the part too as he lunged up and down the keyboard, his coat-tails hanging over the piano stool, a wild-haired artist, profoundly foreign, an East European import from an earlier era. Afterward there was always a reception and dinner for him; surrounded by rich and wrinkled women, his eyes would rove around the room, and when he found me, he shrugged and grimaced from behind their jeweled backs.

Leonora had given me careful instructions about his routine, what to do with his clothes, when he would need the first cup of black coffee that he drank throughout the day. Of course, like everyone else, I got things wrong and he flew into a rage but always one that was tempered to me—that is, to the child I was for him. And with me he got over it more quickly than with the others, and also pitched in to help, so that somehow we muddled through together. Whenever there were a couple of hours to spare in the afternoons, we would go to a local cinema; he liked only gangster or cowboy movies, and since the same program was always playing in the different cities we visited, we saw each one several times. At night I sat up with him in his suite, waiting for the pills without which he couldn’t sleep to take effect. He read aloud to me—Pushkin in Russian, Miłosz in Polish; I didn’t understand but liked to listen to him in these languages that seemed more natural to him than the English he spoke in his sharp Slavic accent. During the time I spent alone in the hotel, I continued with my own writing; it was the first time that I attempted poetry, maybe because he liked it better than prose. He encouraged me to read it to him, listening carefully, asking questions, sometimes making a suggestion that often turned out to be right.

He asked about the years I had spent on my own travels. He was particularly interested in my Buddhist period. He himself was of course a complete agnostic, that was the way he had grown up among those whose mission it had been to overthrow everything. I said that had been my mission too, to overthrow the nihilism they had left us with. “But a nun,” he said, smiling. Although I had long ago given up that ambition, I defended myself. I said that having started on a path, I wanted to follow it as far as it would take me—I had more to say but stopped when I saw the way he was looking at me. His lips were twitching. I didn’t really expect him to take me seriously; it wasn’t only that I was so many years younger than he, I suspected that he took none of us seriously. He even seemed to have the right to be amused by us, as though he were a much wiser person. I don’t know whether this impression derived from the fact that he was a great artist, or from the mixture of the Talmud and Marxist idealism that I thought of as his background.

Since it seemed to take longer and longer for his sleeping pills to have effect, our conversations became more protracted. He wanted to know about my marriage, a subject that I disliked talking about except to say that it had been a mistake. He drew me out about the nineteen-year-old boy who had been the mistake. I admitted that what had attracted me to him was his frailty, which I had interpreted as vulnerability (later he turned out to be hard as nails). It had started when we had bathed together in the Ganges and I saw his frail shoulder blades—it was the first time I had seen him without his robe. “His robe?” Yakuv asked; so then I had to admit that he too had been in the religious life and had been planning to become a monk. I glanced at Yakuv, and yes, his lips were now twitching so much that he could not prevent himself from laughing out loud. I laughed too, maybe ruefully, and he pinched my cheek in his usual way. Only it wasn’t as usual, and that was the first time I stayed with him all night. Although for the rest of the tour we still took separate rooms, we usually stayed in his, except when he was very tired after a concert and then he said I had better sleep in my own little nun’s bed. But mostly he wasn’t tired at all but with plenty of energy left in his short and muscular body. His chest and back and shoulders were covered in grey fur; only his pubic hair had remained pitch black.

He gave me no indication of what to tell or not to tell at home, but it turned out to be easier than expected. Leonora and Kitty were astonished at the way I had stuck it out with him. All their questions were to do with the practical side of my duties—how I had managed to make him catch planes on time and tidy him up for his performances. I gladly supplied them with answers, adding an amusing anecdote or two which made them clap their hands in joyful recognition. They had been there before me. Soon everything settled down. Yakuv and I continued to play dominoes, Leonora fulfilled his daily needs, and he had another home in Kitty’s loft where he kept his furniture and his other piano. Kitty visited us often and she and Leonora met to exchange confidences in their favorite Palm Court rendezvous. They still did not invite me to join them, considering me too young and immature to understand.

However, I understood more than I had done. For instance, I realized that when Yakuv was shut away in his room and there was only the sound of his piano, he was not as oblivious of us as I had always thought. Somehow he was tied to us as we were to him. My mother and aunt never realized that I too was now part of the web that bound them. They took it for granted—and it was a relief to them—that I would accompany him on all his tours. In New York, there was no sign of what went on between us on these tours. Only occasionally, during meals, he slipped off one of the velvet slippers my mother had bought for him and placed his feet on mine under the table. While he was doing this, he kept on eating as usual with his head lowered over the plate, shoveling food into his mouth with tremendous speed.

I was never sure—I’m still not sure—about my father. It was impossible to tell if he suspected anything: he was so disciplined, so used to accommodating himself to difficult situations and handling them not for his own satisfaction but for those he loved. Every time I packed my suitcase to go on tour with Yakuv, Rudy came into my room. I said, “It’s all right: I like it.” He continued to watch me in silence while I happily flung clothes into my suitcase. At last he said, “And your writing?” He sounded so disappointed that I tried to think of something to make him feel better. I said I was continuing my attempts at writing, and in fact, inspired by Yakuv’s performances, I had begun to write poetry. I knew that for my father poetry and music were the pinnacle of human achievement, so perhaps he really was consoled and not only pretending to be so.

Yakuv outlived Rudy by many years; he also outlived Leonora and Kitty. He became a wizened little old man, more temperamental than ever, his hair, now completely white, standing up as he ran his hands through it in fury. He continued his tours till the end and became more and more famous, people lining up not only to hear but also to see him leaping around like a little devil on his piano stool. He made many recordings and was particularly admired for his blend of intellectual rigor and sensual passion. When he died, he left his royalties to me, as well as quite a lot of other business to take care of. Of course I have all his recordings and often listen to them, so he is always with me. I no longer write poetry but have returned to prose and have published several novels and collections of stories. These are mostly about the relations between men and women, which appears to have been the subject that has impressed itself most deeply on my heart and mind. I keep coming back to it, trying again and again to render my mother’s and my aunt’s experience, as I observed it, and my own. This account is one more such attempt.