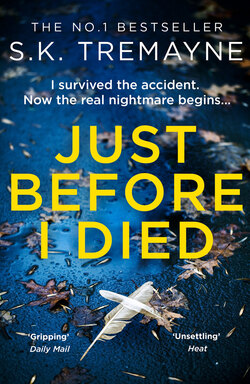

Читать книгу Just Before I Died - S.K. Tremayne, S. K. Tremayne - Страница 8

Huckerby Farm

ОглавлениеSaturday morning

The dead birds are neatly arranged in a row. I don’t know why they are dead. Maybe they were slaughtered, by a domestic cat, in that cruel, unhungry, feline way: killing things for fun. But I don’t know anyone who keeps a cat, not for miles. We certainly don’t. Adam prefers dogs: animals that work and hunt and retrieve, animals with a loyal purpose.

More likely is that these little songbirds died from frost and hunger: this long Dartmoor winter has been hard. The last few weeks the ice has bitten into the acid soil, gnawed at the twisted trees, sent people scurrying into their homes from little Christow to Tavy Cleave, and has turned the narrow moorland roads to rinks.

I shudder at the returning thought, as I cradle my hot coffee and gaze out of the kitchen window. Ice had been a danger on the roads for a while. Yes, I should have been more careful, but was it really my fault? I looked away for a moment, distracted by something. And then, it happened, on the dark road that runs by Burrator Reservoir.

It was just a little patch of ice. But it was enough. I went from heading home at a sedentary pace to being in a car out of control, skidding terribly, ramming the useless brakes, in the frigid December twilight, sliding faster and faster towards the waiting waters. All I remember is a strange and rushing sense of inevitability, that this had somehow been meant to happen all my life: my sudden death, at thirty-seven.

The rising black water had always been meant to freeze me; the locked car doors had always been meant to cage me. The icy liquid in my lungs had always been intended to drown the last of my gasps, on this cold, anonymous December evening on the fringes of the moor, where the bony beacons and balding hills begin their descent to Plymouth.

But it didn’t kill me.

I fought and swam, blood streaming – and I survived. Somehow, somehow. Yes, my memories are still ribbony, still ragged, but they are returning, and my body is recovering. The bruising on my face is nearly gone.

I survived a near-fatal accident and I am determined to number my blessings, as if I am an infant doing sums by counting her fingers.

Blessing number one: I have a husband I love. Adam Redway. He seems to love me too, and he is still very handsome at thirty-eight: with those dazzling blue eyes and that crow-dark hair. Almost black, but not quite. Sometimes he could pass for a man ten years younger, he has that agelessness, despite the toughness of his job; perhaps it is because of his job.

He doesn’t earn that much, as a National Park Ranger, but he adores the moors where he was born, and he adores what he does: from repairing walls so the Dartmoor ponies can’t range too far, to taking troops of school kids to see the daffodils of Steps Bridge, to guiding tourists, for fun, all the way down Lydford Gorge, spooking them out with stories of the outlaws who lived there, in the sixteenth century, the Gubbins who lived in caves, and became cannibals, and died out from inbreeding, and madness.

Adam loves all this: loves the poetry and the severity of the moor. He likes the toughness and the strangeness; he grew up with it. And over the years he has allowed me to become a part of it: we have a happy marriage, or at least a marriage happier than many. Yes, it is regular, ordinary, even predictable. Right down to the sex.

I am sure my friends from uni would laugh at the homeliness, but I find it deeply reassuring. The world turns: rhythmically and reliably. I desire, and am desired. We haven’t made love so much since the accident, but I am sure it will return. It always does.

What else can I give thanks for? What else makes me glad to be alive? I need to remind myself. Because these flashbacks are pretty painful.

Quite often I get sudden, frightening headaches: headaches sharp enough to make me cry out. It’s as if something is crunching in my mind, bone grating on nerves.

Like now. I wince. Setting the big coffee cup by the sink, I put a hand to my forehead, to that tender place where I must have hit the steering wheel, cracking bone and brain and a week of memories into fragments, like a shattered pane of winter ice on a moorland dew pond.

Deep breaths. Deep, long breaths.

Focus on the positive, that’s what the doctor said. Be thankful every day. Makes the healing quicker. Mends the mind faster.

I like my job, working in the National Park tourist office. It’s not the archaeological job I wanted when I graduated from Exeter University. It’s not my dream, and it doesn’t pay well, but I get to write the leaflets, to talk about history, to enthuse to day trippers, and the park authorities let me join the digs in the season, slicing into the turf to find Bronze Age barrows or buried kistvaens – sunken chests – of Neolithic skulls and femurs and backbones, the remains of people who lived here when the moors were warmer, and drier. Kinder.

Better than all that: I love this rented granite house we live in, five miles south of Princetown, lost in the high moorland, a mile from the next inhabited building, the Spaldings’ farm, and two miles from the nearest hamlet, with its pub and tiny shop that sells processed ham and charcoal briquettes, and little else.

I love the wild remoteness, the deep starry skies and deeper silence. I love the dreaming, arthritic, moss-hung rowan trees that line the lanes. I like that the moorfolk call them ‘quickbeams’, or ‘witchbeams’. I also love the battered, stubborn, obstinate history of it all. Huckerby used to be a proper farmstead, and it still has barns and outhouses crumbling in the Dartmoor rains, sprouting cornflowers and campions in the haze of high summer, but the only intact building is the one we live in, a classic moorland longhouse, possibly six hundred years old.

Once there would have been a sizeable family here: humans at the top of the house, animals down the other end. Cattle warming people under the same Devonshire thatch. Now the house is converted, the roof slated, and the interior modernized. Yes, it’s hard to heat and it still gets damp. But it has character. And it is occupied by me, and Adam, and Lyla our daughter, and our two dogs Felix and Randal.

I named the dogs from a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins. I love poetry, too: I write it occasionally, and never show it to anyone. I hide it away, as shyly as my daughter hides her secrets. I would have liked to be a poet, the way I would have liked to be an archaeologist. But that’s OK: because I am happy, I think, and certainly happy to be alive, and I live in a house I love in a place I love with a man I love and two dogs I love and, best of all, with a daughter I wholly adore.

Lyla Redway. The girl who likes to arrange dead birds in rows and curves.

Lyla Redway. The nine-year-old girl out there in the farmyard wearing a blue beanie hat and a thick black anorak, playing on her own as she always plays on her own – or with Felix and Randal, who she probably prefers to any human beings.

I don’t mind this. She’s a different sort of girl: she is herself, her vulnerable, eccentric, funny, kind, lovable self. How many kids would spend a cold frosty morning in January arranging dead birds?

Sometimes she orders stones, or twigs, or bright blood-red berries. Other times Adam comes home with presents he has found on the tors, things he knows she will like – miniature pink snail shells and delicate bird bones and bleached-white adder skulls – and she arranges these faintly macabre moorland treasures into complex patterns: mandalas, hexagons and zodiacs, intricate visual symbols only she understands, imposing a poetic order on her lonely moorland world. Where she reigns supreme.

And sometimes she does nothing. She stands for hours, listening to an unheard music, seeing things invisible to others, or remembering incidents from her very early childhood. I’ve read that these strange traits, the acute hearing, and that remarkable memory, are all part of her condition, almost proof of her condition. But we refuse to have her diagnosed, or examined, despite the obvious signs.

Adam doesn’t want to label her, doesn’t want to put her in a box, and I tend to agree. We don’t want to set limits on her, because she seems happy, despite her isolation, her solitude.

Though maybe less happy today?

Lyla is staring down at the birds. And standing absolutely still. This is common for her: she seems to have no middle ground of normal movement. Either she is silent and frozen, as now, or she is dancing and twirling, skipping up the moorland tors, as if she has energy she cannot endure, waving her hands, nodding and rocking, and talking talking talking, chattering like the River Dart under Postbridge, nattering away to herself, a babble of information stored in her brain from all the books she reads.

Hyperlexia, they call it. Another symptom. Reading too much.

How can that be a thing? Reading too much? I let her read as much as she likes. Entire books in a day, thousands of words every hour. Filling up her hungry soul. Because this is, I hope, my gift to her.

She has inherited her father’s beauty, the nearly-black hair, the piercing eyes, but she has my love for words. One day she might be the poet I never was. She might have the scholarly life I wanted. And I’m glad she got her looks from her dad rather than me. My looks have always disappointed: brown hair, brown eyes, average height, average face, nothing special to look at, just me, Kath, the woman married to Adam Redway, with the quirky daughter, does something for the National Park, lives way out in the middle of nowhere, over near Hexworthy.

Nearly dying in that reservoir is probably the one exceptional thing to have happened to me, the only thing likely to get me noticed.

Except, I don’t want to be noticed.

Opening the kitchen window to the cold morning air, I call out: ‘Hey, sweetie, are you OK? Sure you’re warm enough?’

Lyla does not move. She is still frowning at the dead birds, some of them arranged in lines like the rows of Bronze Age ritual stones out on the moors.

‘Darling,’ I repeat, but not impatiently: I am used to having to press things with Lyla, to repeat twice or three times when she is in one of her more obsessive moods. ‘Lyla-berry, I want to check you’re not cold, it’s freezing out there. Where are the dogs?’

Still no answer. I might have to go outside and literally turn her face to meet mine, to make her realize I am talking to her, that I am interacting, that a person needs a response.

Opening the front door, I walk towards my daughter, my arms crossed against the chilly breeze. ‘It’s interesting that they’re all dead, isn’t it, Mummy?’

Her eyes are bright like her father’s under the blue beanie.

‘Sorry, darling?’

‘All the birds, so many of them, all of them are dead. I checked. So many, there must be twenty of them.’

‘Probably the cold, Lyla. It’s a bitter winter, worse than usual.’ I place an arm around her slender shoulders.

‘Hm.’ She shrugs absentmindedly, stares at the birds.

I follow her gaze, examining the pitiful little corpses. They’re definitely frozen: beaks rimed with white frost. I don’t know what species they are. I can see a thrush, I think, and a robin. Lyla surely knows: she can identify every bird and every mammal, and most of the moorland flowers.

‘Well I thought it was sad, Mummy, sad that they were all dead, so I put them in a special pattern so they could all have a funeral together, and not be lonely.’ She stoops and rearranges two of the birds, delicately realigning them. It unsettles me to see her so careful, so precise. She makes such lovely patterns, but these are dead birds. Where did she get them from?

‘All right, that’s good, that’s good. Do you want some lunch?’

‘Wait. Wait, Mummy. Nearly finished.’

This elaborate game is spooking me. Dead birds arranged in a pattern I cannot quite grasp. All those glassy little bird-eyes, a trail of twinned black buttons across the frigid mud.

Lyla turns one frozen blackbird this way, and then that way.

‘Lyla! Please. Enough now.’

Straightening up, she flashes me a smile. ‘Don’t you want me to spend the day arranging dead birds? Are you saying this is inappropriate behaviour?’

I am lost for words. Until I realize my daughter is joking, teasing me about my anxieties. Lyla can exhibit startling flashes of adult humour, insightful, surreal, and self-aware. It’s one of the reasons we’ve resisted that diagnosis.

‘No, I think it’s perfectly fine to arrange loads of creepy dead birds in rows and circles.’ I laugh, and hug her again. ‘What kind of birds are they, anyway? And what is the pattern, is it a face?’

But now her head is turned, looking down the farm track, past the conifer plantation, past Hobajob’s Wood, as if she can hear something. In the far distance. I’ve known her to hear cars minutes before they arrive, long before anyone else.

‘Lyla?’

What can she hear? A raven makes a cronking sound overhead as it wheels across the dull grey sky. Yet her focus seems to be on something else, further away. What is she sensing, coming towards us, down from the tors? The memories hurt. My head stings with pain.

‘Lyla.’

No reply.

‘Lyla, what is it, what can you hear?’

‘The usual man, Mummy, the man on the moor. That’s all.’ Her words are a ghostly vapour in the cold. Her anorak is unzipped and I see she is wearing only a T-shirt underneath. She should be freezing, and yet she never seems to suffer from the cold: she likes the fierce Dartmoor winters, same as her dad. They both relish the cold. The snow. The icicles that hang from the splintered granite. ‘You know, Mummy, that if you see a lot of crows they are rooks, but a rook by itself is a crow. Did you know that?’

I reach for her once more. ‘Lyla.’

She squirms away from my touch. ‘Don’t touch me, Mummy. Leave me be.’

She is snarling. Lyla does this when she is angry or alarmed or overstimulated, she snarls, grimaces, and waves her hands. She does this at school as well: she can’t help it, but it means other children laugh at her, or are scared by her. Isolating her further. She has so few friends. She probably has no real friends.

‘Lyla. Stop this.’

‘Go away, grrr …’

‘Please—’

‘YARK!’

There’s nothing I can do. I step away, watching my daughter as she goes running to the farmyard gate, calling for the real dogs: I can hear them yapping, see our two big mongrel lurchers galloping after her.

She could be gone for another two hours now, half a day even, running across the fields, romping through Hobajob’s, hunting for that Saxon cross lost in the nettles by the brook, with Felix and Randal on each side. Adam supposedly bought the dogs for Lyla, but he loves them as much as she does. They hunt, like proper dogs. They bring back dead rabbits, necks lolling, blood dripping from their muzzles. He likes to skin these hot, reeking corpses in front of Lyla, teaching her authentic Dartmoor ways, tossing gobbets of raw meat to the hungry dogs. Eat them up, you eat them all up.

Lyla is far away in the distance.

What can I do?

Let them play, I think, let them go. Lyla is clearly still upset about my accident. We’ve tried to talk to her about it, as gently as possible, I’ve told her I hit some ice and veered into deep water. We’ve spared her too many details but she will surely have heard stuff from kids at school, in the papers, on the net. We’ve also told Lyla that my memories are hazy but that they will return. Retrograde amnesia. Common after car accidents, caused by the brain ricocheting inside the skull.

Back in the kitchen I wash the coffee mug in the sink and gaze out of the window. In the distance I hear barking, getting nearer, louder. Then they come bursting through the door, the dogs happy, big and growling. Lyla lingers in the doorway, oblivious, it seems, to the bitter wind at her back.

‘Daddy is on the moor again.’

‘What?’

She gives me one of her blank, impenetrable smiles. ‘He’s out there again like he’s watching us, Mummy. That’s Daddy’s job, isn’t it?’

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘He’s a park ranger. He has to patrol everywhere, looking out for people.’

Lyla nods and shrugs, and pursues the dogs into the living room. I stare after her, wondering how she saw her father. He’s meant to be working in his normal patch, way past Postbridge. What is he doing down here? Maybe Lyla is just confused or upset. And I can’t blame her for this dislocation, this bewilderment.

Because her mother nearly died. Leaving her alone, forever.