Читать книгу The Future of Difference - Sabine Hark - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

‘The Rotten Present’: A Plea for Friendship with the World

‘I wish to defend this entire rotten age, the rotten present. It’s all we’ve got. It’s the only life that is available to us. It, and no other, harbours the substances that may unleash our powers.’1

– Christina Thürmer-Rohr, 1987

‘SEEING WHAT’S BEFORE US’

‘Can’t you see what’s before you?’2 What it means to be asked this question, typically in tones of irritation, is a matter the philosopher Nelson Goodman discusses in his book Ways of Worldmaking. He personally liked to answer the question: ‘That depends.’ That is to say, the statement ‘the earth moves’ is just as true as the statement ‘the earth stands still’, since both statements simply depend on their own distinct frame of reference.3 Is Goodman here legitimating the ‘post-truth’ era in which, according to a great number of journalists and commentators, we now live, defining truth in terms of whatever generates the most clicks? On the contrary: what may appear at first glance to be a radically relativistic position that does not want to know the difference between opinions and facts is, in reality, a conscious exercise in ‘irritating those fundamentalists who know very well that facts are found, not made, that facts constitute the one and only real world, and that knowledge consists of believing the facts’.4

Above all, Goodman’s reflections constitute a plea for examining the conditions that make statements of fact possible, for clarifying ‘what is before us’ in the first place and guarding against the ‘view from nowhere’. Second, despite or perhaps because of the growing importance of a certain epochal ‘post-facticity’, Goodman makes it possible to think about what it means that facts are not simply given: that is, that they are not outside the social unfolding of history. We create ‘world-versions’ – and thus facts – he writes, ‘with words, numerals, pictures, sounds, or other symbols of any kind in any medium’.5 And, Friedrich Nietzsche reminds us, ‘it is enough to create new names and estimations and probabilities in order to create new things in the long run.’6 Although we do contend, therefore, that worlds are produced and not simply found, we do not espouse the view, critically described by Pierre Bourdieu and Judith Butler, that the existence of things depends entirely on their names, that is, on ‘performativity’s social magic’.7 We simply deem that our perception of the world, and the way we designate it, shapes what we perceive and how, at a fundamental level; and that it determines what, as far as we are concerned, it really is. Indeed, according to philosopher John Searle, our ‘entire institutional reality’ is created by ‘linguistic representation’.8

The consequences of this are no more, and no less, than this: reality and language, perception and truth, facts and interpretations are not only interlinked, but constitutive of one another. That is no trivial insight, and it demands awareness of the complexity and, sometimes, inscrutability of the relationship – inscrutability being, as it is, one of the essential characteristics of the modern era. The philosopher Bernhard Waldenfels contends that, in modernity, there is no longer any form of order that exists a priori while still encompassing the observer.9 Waldenfels, here, is essentially describing the condition of contingency. That is: it is equally possible for all things to be one way as it is for them to be another, because there is no necessary reason for anything existing. Not our actions alone, but even the sphere in which these actions take place, contain a multiplicity of possible versions of themselves. And, ultimately, this quality of impenetrability, which marks the very practice of modern science, demands that we understand the production of knowledge as always open-ended and provisional – the latter being a paradigmatic expression of the norm of ‘organized skepticism’ advanced by Robert Merton.10 The opacity in question may even have intensified in recent years as a result of the increasing – or, at least, increasingly noticeable – complexity of the social.11

THE COLOGNE INCIDENT

Seeing what’s before us and determining what matters – that is the concern of this book. The occasion for it? Whatever transpired on New Year’s Eve 2015 in Cologne: a night that stands for a tectonic shift in Germany’s social fabric, albeit one whose reach remains as yet unknown. As we have noted, whatever actually transpired soon crystallized into an ‘event’, far in excess of the real incident(s). ‘Cologne’ is now the name of that event: the name for an ensemble made up of ‘words, numerals, pictures, sounds, or other symbols’ that has acquired the capacity to ‘create new things in the long run’.

Following Stuart Hall, we apprehend ‘Cologne’ as one element in a ‘regime of representation’ that encompasses ‘the entire repertoire of imagery and visual effects’ by which ‘difference’ is represented at any historical moment.12 Within any such regime, everyday differences – ethnic and cultural labels, for instance, or gender markers – are (re)arranged in complex ways so as to bring them under a unified provisional structure. It is by referring to this unified structure that people are able to make meaning and organize the world for themselves. ‘Cologne’ is the name of one such structure. But what is it, specifically, then, that ‘Cologne’ renders legible? ‘Cologne’ organizes the difference between ‘us and them’, which is to say, in Hall’s famous formulation, the relationship between ‘the West and the rest’.13

Regimes of representation, as Hall understands them, do not simply describe differences. On the contrary: the defining feature of any regime of representation is the way it produces difference. Regimes of representation govern by virtue of the fact that differences are given to us in any case. We grapple extensively with this question of the distribution of the sensible in this book: that is to say, with the texts through which ‘Cologne’ was made visible. In this task, we understand texts and images, with Alex Demirović, as active ‘intervening’ entities which ‘seek to create constellations and contexts’.14

However, to assert that differences are performative – that is to say, made visible by texts and images – is not the whole story. For Demirović, a text or an image is always ‘fundamentally dialogic – practice-based – because its emergence inevitably changes the constellation of already-existing texts, the relationship between the said and the unsayable, and thus, the context itself’. Texts and images do not, therefore, acquire meaning by themselves, in themselves or for themselves; they do so only ‘as discursive processes, as specific events in a constellation’. By ‘being part of a force-field, they are themselves co-producing and shaping’, they ‘respond to one problem or another, arising in order to take something up, displace it, override it or change it’. Lastly, we will state a truism, but an essential one: images and texts determine neither perception nor reality. They co-constitute both, and this constituting depends in turn on people’s actual practices of appropriation in specific contexts.

It took less than a year from the emergence of that node called ‘Cologne’ for it to become part of Germany’s ‘objective’ history. ‘After Cologne’ is now a dividing line in our calendars that frames the time that has passed since – and possibly the time before it, too. In any case, that New Year’s Eve was the moment when the parameters of all kinds of debates shifted irrevocably: debates around culture, ‘race’, gender, religion, and morality; on the management of migration and asylum; on matters of sexuality and gender; on criminal prosecution policy around sexual violence; on the rights of immigrants; on relations between native Germans and foreigners; on the interconnectedness of racism, sexism and feminism; and on immigration, integration, and internal security.

The effects precipitated were complex and difficult to summarize under the heading of one common denominator. Upon closer inspection, though, it seems safe to say that the dynamics unleashed by Cologne have been characterized by a certain core ambivalence that is, in practice at least, always controlled and regulated by fundamentalist rhetorics. We are fascinated by these rhetorics. As we hope to show in the following chapters, sexual politics has once again become active in the service of the production of racist truths.15 Feminism is once more being used to bear witness to the ‘incompatibility’ of Islam with Western values (such as gender equality or tolerance for LGBTQI* existence and lifestyles) and to legitimize the violence of European border regimes.16

There is nothing remotely new about the construction of a zero-sum game involving feminism and the foreigner; nothing original about mobilizing resentment off the back of an imagined dichotomy between women’s rights (and those of other sexual and gender minorities), on the one hand, and everything non-Western or foreign, on the other. The unforgettable populist rallying cry of the German minister of the interior, Thomas de Maizière, in April 2015, ‘Wir sind nicht Burka’ – ‘We are not burka’ – was but one among a slew of fresh examples.17 To de Maizière and many others, ‘Cologne’ was the definitive proof and manifestation of Samuel Huntington’s otherwise widely repudiated view that the source of all twenty-first-century conflicts lies in ‘culture’ (the ‘clash of civilizations’ hypothesis).18 As that camp has, ever since, made a habit of asserting, any prospect of harmonious European or American coexistence with immigrants (especially Muslims) from the Global South is unfortunately fatally compromised – by ‘cultural differences’.

AMBIGUOUS ENTANGLEMENTS: RACISM, SEXISM, FEMINISM

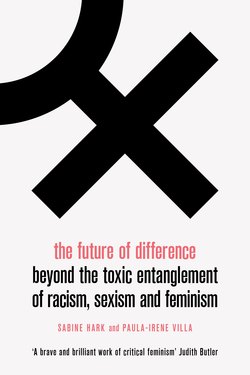

This book represents our attempt to gain some purchase on these contemporary entanglements, these ambiguous imbrications of racism, sexism and feminism in the present moment. We regard it as an exercise in critical thinking in which we bring together our sociological knowledge with feminist theory, postcolonial analysis, queer and critical race studies, and border or migration studies. These fields are all part of the West’s internal critical tradition, a tradition which, as Foucault argues in Discourse and Truth, calls into question the very mechanisms by which the ‘truth’ is culturally produced.19 The paradigmatic starting point these academic domains hold in common (at least in theory) is essentially Marx’s insight that critique is always immanent, that is, it must appreciate that it is itself part of what it criticizes, such that the critique itself becomes subject to critique. In Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s words: ‘This impossible “no” to a structure which one critiques, yet inhabits intimately, is the deconstructive philosophical position.’20 In our view, it is the heterogeneous field of feminist thought, more than any other theoretical project, that has set itself the challenge of grappling with the aporias that arise when we acknowledge the immanence of critique, paying attention, in particular, to the risk of reinscribing an axis of difference – sexual and gender difference – in the very act of questioning it.

Feminist theory, therefore, has always considered ‘the critique of all discourses concerning gender’ vital to feminism, ‘including those produced or promoted as feminist’ – to quote Teresa de Lauretis.21 It has therefore not only rejected the concept of ‘the woman in general’22 but sought to ask who is actually represented by specific usages of the category ‘woman’, making the production of that sign of difference and discrimination itself the object of inquiry. The history of feminism is rich in examples of what we mean, dating back to the mid-nineteenth century. Famously, in 1851, at a gathering of white bourgeois American women fighting for women’s suffrage, the black abolitionist and former slave Sojourner Truth approached the congregation demanding to know whether or not she qualified as a woman. The question put to the gathering of women’s rights activists – ‘Ain’t I a woman?’ – drew logically from Truth’s experiences of toiling as hard and eating as much as any man, being flogged, and never once experiencing any of the paternalistic gallantry the white majority took for granted on the basis of their femininity.23 Ever since then, the question ‘Ain’t I a woman?’ has served as an effective tool for dismantling racialized, ethnocentric or heteronormative definitions of gender and femininity.24

Thus, ‘what appear as separable categories are, rather, the conditions of articulation for each other.’25 The resultant questions have been raised again and again in the history of feminist theory, as in Judith Butler’s formulation: ‘How is race lived in the modality of sexuality?’ and ‘How is gender lived in the modality of race?’26 And, equally: ‘How do colonial and neo-colonial nation states rehearse gender relations in the consolidation of state power?’ and ‘Where and how is “homosexuality” at once the imputed sexuality of the colonized, and the incipient sign of Western imperialism?’27

Ultimately, feminism has to be understood as a project defined by its internal contradictions, discontinuities and antagonisms; as a struggle over meanings. Feminist thought has no unitary canon, but rather represents a generative field full of disparate movements. More than the sum of its parts, feminism is not only the aggregate of disparate critical analyses of gendered social inequalities and exclusions, dominant discourses and cultural regimes; it is the materialization of a process of recognizing the situatedness of all knowledge production.

Of course, this principle of critical self-reflexivity – this fundamental methodological doubt – also informs many of the branches of the humanities and social sciences we borrow from in these pages. Indeed, all the ‘critical traditions’ (by which we mean disciplines that cleave to Marx’s orientation towards immanence in the broadest sense) – as well as the newer fields of systems theory, actor-network theory, science and technology studies, and cultural studies – direct their practitioners not to reify their own categories and to be wary of their (at least implicit) normative power. And yet, unfortunately, ‘problematic’ categories (and what would an unproblematic category look like, anyway?) do not simply give up and go away. Quite the contrary. We are stuck with negotiating the manifold problems of categorization and classification precisely because we know their power to generate worlds, and because, in the end, we think that concepts can actually mount a resistance to power.

Our reflections, in summary, are guided by the hypothesis that ‘Cologne’ is bound up in a series of highly effective ideological operations – mainly objectifications of difference – which now serve to shore up social hierarchies in Germany. We will test this hypothesis in the following chapters. Once again, we do not argue for denying differences, ignoring them, or even abolishing them. Quite the reverse: we urge remembrance of the fact that sociality itself would be impossible without differences – even as it is governed by them. The point, for us, then, is to develop an ethics of difference that is aware of its own sociality: an ethics that does not pretend differences exist in and of themselves, outside of social practice. This mode of relating would defend against the dehumanizing operations of contemporary fundamentalist differentiation which give us, for instance: ‘the black person’, ‘the asylum seeker’, ‘woman’, and ‘man’. It would simultaneously value the way that differences make practice and perception – not least the practice of critical differentiation – possible.

A MATTER OF CONCERN

We seek to distance ourselves equally from those who would have us believe that the world consists of opinions as from those who deem knowledge to be a simple matter of acquainting oneself with the facts. As urgent as it is – and it is, indeed, more urgent than ever before – to combat lies with facts, in truth, reality is not (only) made up of facts. For the simple reason that facts do not make up the whole of worldly experience, as Bruno Latour contends, real-ness has to be ascribed to them. We, as authors, do not therefore rely solely on matters of fact; rather, we adopt ‘a realism dealing with matters of concern’.28

‘Cologne’ is one such matter of concern, in the first place because, well, it concerns us. Second, as it clearly isn’t reducible to its punctual components, the sum of certain localized happenings, it cannot be reduced to a fact. To continue with Latour’s framework, however, we know that several conditions have to come together at once in order for a ‘matter of concern’ to take shape in a lasting way. Additional forces have to be in play; simple occurrences alone do not make reality. A ‘matter of concern’ comes into being as a result of media attention, political interpellation, cultural, religious, governmental and other interpretation, police action, scientific expertise, and much, much more. Since the world is not found but made – we make it – it behooves us to understand the mechanisms behind this making, this gathering up of the necessary components to turn mere objects into a public ‘thing’. Only then will we appreciate the opportunities afforded us to remake the world otherwise. And, after all, we must do so, for, as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie reminds us, ‘It does not have to be like this.’29

We are constantly hearing from those who profess to know exactly what the nature of the reality we inhabit is. We, by contrast, want to start by asking nothing but questions. If it is the case that ‘it is enough to create new names and estimations and probabilities in order to create new things in the long run’, then we must recognize that the world is constantly evading us, reforming itself ahead of us, just outside our grasp. As researchers, we are, in fact, ourselves part of this very process. Our scholarship is part of the creation of new things – including new perspectives on the world. Just like public politicking and media discourse, our endeavours manufacture worlds and (in Ian Hacking’s phrase) ‘make people up’.30 Words do things. It really cannot be stressed often enough.

Whenever words and concepts coagulate into operations of categorical classification, they risk generating what Sighard Neckel and Ferdinand Sutterlüty call ‘qualitative judgments of otherness’ (qualitative Urteile der Andersartigkeit) targeting individuals and groups – that is to say, drawing symbolic lines of membership or exclusion.31 They produce and reproduce – in ways always intimately bound up with whatever news developments, media narratives and political agendas are circulating in the contemporary political conjuncture – entire modes of social valuation. And, ultimately, these words and concepts flow – mediated by culture – back into the social reservoir of knowledge. This collective reservoir of meanings is what all members of society then inevitably draw upon when forming their notions of ‘self’ and ‘other’: making ‘judgments of otherness’ and deciding who is entitled to what, what is collectively owed to whom, and who isn’t even worth our attention.

INTERROGATING DIFFERENCES

Critical thinking must always, for these reasons, ensure it is not participating in the ongoing, violent process the nineteenth-century philosopher Hedwig Dohm referred to as Versämtlichung (otherization) of the world. Versämtlichung describes the epistemic mechanism by which – irrespective of the cause or political banner under which it takes place – we construct, ossify and maintain imaginary others. To avoid it, we must constantly question – indeed, call into question – all evidence, superficial or otherwise, of non-negotiable identity-based differences wherever they arise. Differences, be they markers of sexual, gendered, cultural or ethnic variation, should not be taken for granted or regarded as indisputable. Rather, we should understand them as contingent realities that are the product of specific historically and institutionally situated struggles. Differences, in other words, are the result of specific discursive strategies, practices and modalities of power. They are always provisional, but this does not mean they are in any way ephemeral or fleeting.

For example, in statistical and bureaucratic settings, social traits are not only attributed to social groups, they inevitably also act as a post-hoc rationalization of inequality, contributing to the consolidation of uneven geographies, especially when these (as signifiers of difference) have coagulated into full-blown categories of essentialized identity.32 As the feminist social theorist Regina Becker-Schmidt contended some time ago, in order to really understand social inequality, we first have to understand the social force of attribution itself.33

To do that, it is just as vital that we learn how to liberate difference, not just from the rigid dyad of the universal versus the particular, but from all essentializing mystifications: the ‘eternal feminine’, ‘Africa, the dark continent’, ‘men who don’t listen and women who can’t read maps’, and so on. Hedwig Dohm was amazed at the ‘incomprehensible contradictions’ that characterized male judgments about women in the nineteenth century. She wrote:

Woman is a potpourri of antagonistic qualities, a kaleidoscope that can bring forth any given nuance of character or colour if one simply shakes it up and down. According to the critical mass, the basic ground of the feminine spirit seems to be a fog of sheer chaos, a primal mist whence the voice of Man’s Creator can simply call into being whatever properties Man so happens to desire.

It is thus crucial that we learn to decrypt all binaries, perceiving that they bind opposites to one another in the act of defining and separating them. This endeavour not only constitutes an end in itself (for example, this is the entirely legitimate form it takes in academia, notably in gender studies) but, further, helps disembed and make visible the mechanisms of real-life domination inherent in discursive dualism. It is not, in that sense, sufficient to grasp the process by which social actors get ‘classified’; we must go beyond that and interrogate the conditions under which classificatory distinctions are hatched. Instead of accepting a given identity as a premise when thinking about difference – that is, presupposing that that identity exists, thereby removing it from criticism – as we’ve suggested, we have to think in difference about difference, and learn to differentiate between differences. What matters most to us is recognizing that some differences are harmless, even joyful, while others hold in place the poles of a global matrix of domination, as Donna Haraway attests.34 So, it is not so much whether but, rather, the question of how differences are activated politically that spurred us on when writing this book.

RESPONSIBILITY, SITUATEDNESS, ‘FRIENDSHIP WITH THE WORLD’

Totalizing ways of seeing – ‘the Muslim’, ‘the woman wearing a head-scarf’, ‘the economic migrant’, not to mention ‘feminists’, ‘identity politics’, ‘Germans and Islam’, ‘women and men’, ‘whites and blacks’ – are, needless to say, simply not an option for us. Not only do they mask the internal heterogeneity of all things, they deny the partiality and positionality of every speaking position. And, ultimately, any view that is not considered ‘partial’ is always going to invoke ‘the’ unmarked category, the putatively white, male, cis, heterosexual, able-bodied subjectivity that history has enforced as a self-evident universal. The peculiar power of this unmarked position lies, paradoxically, in its structural limitations. That which is ‘us’, that which is ‘normal’ – imagined as universal – enjoys the relative lack of scrutiny afforded by its place in the shadow of the particular, the ‘marked’, and the divergent, which we force into the light. It is imperative to constantly ask, then, why what we see is what we see; where are we seeing from; and what are the limits on this seeing?

Once again: what we are describing here is a practice of critical, self-reflective positionality. By no means do we mean to vindicate, in this, a trivial relativism. At stake is our ability to see what is available for us to see, to perceive what we have been taught to perceive, and to know that something is missing. This means becoming willfully alert and curious with regard to that which is hidden (in part because we are hiding it). It means making things into matters of concern. Relativism, on the other hand, is a way of claiming to be nowhere and everywhere the same. According to Haraway, relativist accounts of the relation between identity and positionality are usually just a way of denying responsibility and of preventing us from critically responding to it.35

In contrast, Haraway’s theorization of situatedness insists on shared responsibility for the practices that give us power – the authors of this book, for example, are called to account for our responsibility as privileged workers and intellectuals. This isn’t about a ‘fundamentalism of positionality’ that seeks to derive an inescapable standing in the world from a given position occupied by the speaker within the space of the social.36 ‘Positionality’ does not imply that a particular social position – female, Jewish, lesbian, middle class, Catholic, working class, migrant, refugee, white, Bavarian – inevitably entails any particular opinions, attitudes or beliefs stemming somehow, ineluctably, from the position in question. It certainly does not define the experiences that can be lived by individuals positioned thus. Quite the reverse: we understand positionality to be all about recognizing that social positioning does things to us – things we cannot really help – in dynamic and complex ways. What we can do, however, is adopt an attitude vis-à-vis our positionality, cognizant of the fact that it is in our power to do things with it in return. In fact, it is probably impossible not to.

The alternative to, on the one hand, epistemic totalitarianisms that lump the world into opposites and, on the other, relativisms that do not care about it at all, can only be ‘partial, locatable, critical knowledges’.37 Solidarity is the name for this web of connection in politics; in the field of epistemology, it is called dialogue, conversation, debate. Our book is committed to it. We hope this will contribute to ‘a more adequate, richer, better account of a world’ but also a ‘critical, reflective relation to our own as well as others’ practices of domination and the unequal parts of privilege and oppression that make up all positions’, to quote Donna Haraway again.38 For us, this has as much to do with ethics and politics as it does with epistemology, knowledge or truth.

Regrettably, responsibility is widely thought instead ‘in terms of the obligation to answer for oneself, to be the guarantor of one’s own actions’, to quote Achille Mbembe’s critique.39 What we require is a different stance – seeking to think not so much about as with the world – namely, a stance of empathy qua intellectual orientation. This intellectual empathy embraces the influence of the world, neither grasping all random feeling willy-nilly nor attempting to defend itself against vulnerability, against touch. Nevertheless, it enacts ‘resistance to that which is forced upon it’, as Theodor Adorno writes in Negative Dialectics.40 It raises the question, posed by Judith Butler, of whether one can ‘lead a good life in a bad life’ – that is, a world in which ‘the good life is structurally or systematically foreclosed for so many’.41 It demands that we do ‘sciences from below’, making sense of the world through epistemic processes that centre the perspective of the most marginalized.42 One thing to centre, to give just one example, might be the phenomenon known as ‘household air pollution’, which, according to a World Health Organization (WHO) study, accounts for the premature death of some 4 million people annually, most of them women and children.43 Scientifically and politically, such forms of slow violence would certainly become public ‘things’, ‘matters of concern’, under a regime of radical empathy. Christina Thürmer-Rohr had a memorable name for the epistemic commitment we are talking about. She called it ‘friendship with the world’.44

DOUBT IN DOUBT

To espouse friendship with the world is to modulate how we act every bit as much as how we think (insofar as we would even wish to establish a difference between the two). It is to hesitate before passing judgment, but it is never indifference. It is to be sceptical of affective reactions without, however, cynically rejecting affect. Cynicism serves, in a sense, to augment its bearer, helping her gain a putative distinction vis-à-vis whatever it is othering. But it can offer nothing by way of justice to those who will suffer from the resultant loss of solidarity. The attitude to the world that we want to foster, in contrast, seeks to acknowledge what is known while, at the same time, defamiliarizing and alienating that knowledge – re-examining things from perspectives different from one’s own – and thereby expanding one’s perception of the world. This, in turn, demands that we challenge ourselves, as far as possible, always to spell out our reasoning, instead of relying on local and available repositories of common sense and general truths.

Hannah Arendt, following Immanuel Kant, referred to such a disposition, premised on the ability to take others’ perspectives into account, as an ‘expanded’ practice of thought.45 Instead of adding to the great number of urgent diagnoses people are producing at the moment – instead of generating value for the seemingly ever-intensifying ‘attention economy’46 – we trust ourselves, even at this troublesome juncture, to doubt. We are seeking to go against the grain of what Pierre Bourdieu calls ‘doxa’, that is, the ensemble of that which is taken for granted and unquestioned.47 Instead of inferring contexts for things, we think it more apt to ask: What is it that is brought into context for us, such that an emergency, an urgence (urgency) or ‘state of exception’,48 in Foucault’s terms, is created?

And what is the precise nature of this ‘emergency’ situation anyway, which is supposedly caused by excessive liberality around questions of identity, too much political correctness, too little attention to the social mainstream, too much consideration for the concerns of sexual, gender and racial minorities – all of which, so its proponents claim, is what made right-wing populism possible?49 What kind of ‘emergency’, when the challenges associated with immigration and integration have to be negotiated primarily as a matter of internal security to be tackled, among other things, by a garment police50 – and when the topics of terrorism, sexual wrongdoing and Islam must be treated as an indissoluble unity?51 Meanwhile, the right-wing violence that has long been endemic to the country, such as the murders committed by the neo-Nazi National Socialist Underground (NSU), are not regarded in this way.52 Rather, they are routinely treated as non–ideologically motivated acts by individuals.53 Why does the everyday, systematic dimension and massive scale of sexual violence against women, and of violence against refugees (their persons, shelters, dwellings) – including violence against people perceived as migrants – not constitute a ‘state of emergency’ in the same way as did the violent attacks in Cologne?

Should we agree that it is an ‘emergency’ that Germany is a divided country,54 a society in which, as Oliver Nachtwey contends, ‘collective fear of downward mobility seems to be universal’55 – driving citizens into the arms of the far-right Pegida and AfD? Or should we not first ask: Whose precariousness is visible and perceptible to us, and whose is not? Whose vulnerability do we take seriously and understand as our own? Is the embitterment of the alienated, predominantly white, heterosexual, ‘autochthonous’ German middle class the only form of resentment that counts?

And, finally, why should we entertain for a second the idea that an individual’s gender performance, deemed deviant in the eyes of the presumed majority, somehow leads to widespread insecurity, aggression and violence? If this were the case, would not lesbian, gay, bisexual, intersex, trans and genderqueer people, whose sexuality is relentlessly called into question and rendered permanently insecure, by the same logic, be especially violent and aggressive? And wouldn’t everybody then have to demonstrate the utmost understanding for that aggression? In short, then, is the dominant description of a current ‘state of emergency’ actually an accurate or useful description? That is to say, does it provide answers to the big questions concerning the society in which we actually live: What holds it together? What links exist between inequality, domination, integration and social conflict? And how might we (re)establish social bonds?

To be frank, we do not have answers to these questions either. Nevertheless, we believe that the question of what constitutes the exception – the sense of urgency justifying emergency measures – must be made far clearer than it has been previously. That being achieved, those of us who do not want to settle for a strategy of reductivism – or who have no desire to combat facts with affects, and statistics with feelings – would be hard-pressed to avoid treating matters of concern (that is, the things that concern us) with compassion, empathy and the determination to differentiate.

‘MORAL-SOCIAL SCIENCE’

Any good analysis of complex realities therefore requires of us an empirically oriented mode of thought – but one that is capable of appreciating the mutually contingent nature of various differences. It requires, in other words, ‘a moral-social science in which moral considerations are not suppressed and set aside, but systematically blended with analytical reasoning’, in the formula of Albert Hirschman.56 Of course, as Christina Thürmer-Rohr already advanced thirty years ago – in her analysis of the entanglements of femininity, feminism and patriarchal rule – categories like sensitivity, care, empathy, compassion and tenderness are neither context-free nor morally innocent.57

Rather, they are components of a relational morality which, albeit beautiful, is ultimately an abstraction. So even values like morality, dignity and respect must be critically unpicked, precisely because we cannot do without them as we go about the urgent task of reviving democracy. ‘In what social location’, we must ask, are empathy, concern and compassion to be found? How can they be tied to analyses that take us beyond mere fleeting affect? ‘Whom do they serve, whom do they benefit, who mobilizes them, whom do they fail, do they break, to whom do they turn to their opposite?’58

One way of summing this up is to stress, once again, the importance of understanding that our entire way of life is predicated on relations of subordination and its opposite, superordination: the fixing of things within endless hierarchies. These often subtle yet violent differentiations determine almost everything – actions, attitudes and feelings – for all of us. And, as we’ve stated, it is not the differences themselves that are the problem here, but the dominational logic of (de)humanization that subtends them and inflects the things they designate: man, African, victim, woman, human, queer, foreign, citizen, and so on.

DOMINATION CULTURE

Our book seeks to contribute to an understanding of the mechanism we call ‘othering and ruling’. We are convinced that difference is not, in and of itself, the problem: rather, the problem is the way differences are anchored, made meaningful and roped into everyday political life. And it is precisely for this reason that we feel it is crucial to understand the difference between at least two different kinds of differences. On the one hand, there are differences that are themselves committed to the knowledge that nothing on earth, especially not the human, is thinkable in the singular; as Hannah Arendt writes, ‘Not Man but men inhabit this planet.’59 On the other hand, differences are often conceived and motivated by domination. The latter kind of differentiation is best understood as driven by the will to misunderstand the many and ‘reduce them to quantity – to the number one’, in Christina Thürmer-Rohr’s formulation.60

We advance the notion of ‘othering and ruling’ so as to highlight a mechanism we take to be a core part of what the German theorist Birgit Rommelspacher calls ‘domination culture’.61 Rommelspacher’s framework designates a comprehensive social logic made up of an intricate web of mutually interacting dimensions of power. Above all, the term ‘domination culture’ focuses on the sphere of culture: the domain in which, today perhaps more than ever, the production and reproduction of difference, discrimination, segregation, vulnerability and danger are negotiated. And, finally, ‘domination culture’ sums up Rommelspacher’s contention, which we’ve already alluded to, that our entire way of life is couched in ‘categories of subordination and super-ordination’.62 This includes, of course, the way we create images of other people, and represents a tendency that has rapidly taken on an unprecedented virulence, what with the worldwide right-wing and populist-conservative capture of liberal democracy in recent years.

The French sociologist Michel Wieviorka, too, has long presented similar arguments, emphasizing the pre-eminence of culture. For Wieviorka, economic inequalities and social injustices aren’t just things that affect people; rather, as dimensions of discrimination and segregation, they define the most fragile and the most vulnerable in cultural terms that can then all too easily be expressed as natural characteristics (i.e., naturalized).63 Whenever we speak of ‘cultural differences’, we cannot, according to Wieviorka, remain silent for long on the subject of social hierarchy, inequality and exclusion. Questions of cultural right (or rights), moreover, simply cannot be discussed without involving social injustice in the debate.

Rommelspacher understands culture in a very broad sense as the ensemble of social practices and shared mediations through which the current constitution of a society and, in particular, its political-economic structures and its history, are expressed.64 Moreover, according to Rommelspacher, the dominant culture determines all behaviour – ‘the attitudes and feelings of all people who live in any given society’65 – and mediates between the individual and social structures. In Western societies, or so her book Dominanzkultur contends, this dominant culture is also a domination culture, which is to say, a culture ‘primarily characterized by different traditions of domination in all their different dimensions’.66 What we are scrutinizing, then, is these many and particular ‘forms and modes of domination’ which, as Beate Krais and Gunter Gebauer show, are encoded in our worldviews, constantly confirmed to us by our systems of reasoning, and transmitted to us via the social institutions that, in themselves, produce culture.67

Culture, then, is not a specific constellation of traditions, mores, myths and cuisines made up of various, alternately regional, religious or historical essentialisms. Culture is both the complex location and form of production of social knowledge and meaning. It is an unevenly available and authoritarian sphere that is productive of inequality – thus paradoxically not ‘merely cultural’,68 as Judith Butler says, but linked to all kinds of concrete material issues that determine access to resources. It is also, on the other hand, a place where societies and their members make sense of these circumstances, and thus provides the (only?) possibility of changing these conditions. Culture is form that is simultaneously indestructible and always in flux. Culture is the circulation of meaning and signification, which are constantly being limned and remade anew by that circulatory movement.

Prime among the relations of inequality culture reproduces (inequality of access, of participation and of interpretation) are: sexism and heteronormativity, racism, and class. These, however, are not to be understood as social divisions operating independently, but rather analyzed as a complex intersectional constellation. It does not make sense to categorize them, as many have unsuccessfully sought to do, in terms of ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ contradictions; nor to classify them, for example, as ‘vertical’ versus ‘horizontal’ axes of inequality; ‘ascriptive’ traits as opposed to socio-structural inequalities; or neatly partitioned struggles for ‘recognition’ on the one hand and ‘redistribution’ on the other. This is a decidedly erroneous approach that fails to recognize the extent to which visibility, recognition and representation are systematically connected to the flow of resources, power and opportunity.

For the aforementioned French sociologist Michel Wieviorka, the cultural and the social are always already ‘mixed’ to begin with when it comes to the contemporary formulation of the social.69 Power relations simply cannot be mapped according to a hierarchy in which the precise configuration of ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ contradictions can be precisely established. People are never simply one thing or the other, never ‘first’ a privileged researcher and only then female, lesbian or heterosexual, for example, with or without living children, with or without proletarian roots or ‘some kind of migration background’. Identities – understood as relations to the self, as the question ‘who am I?’ – are not constative things: they are neither given nor fixed. Rather, they are expressions of social relations. It’s up to us what we do with them.

NO BLUEPRINTS

For all these reasons, we strongly oppose any attempt to interpret a given social position as a blueprint for an identity, or even for attitudes. If you are white, for example, you may not necessarily think or act in racist ways, but you have to acknowledge that you benefit from the accrual of a racist dividend. This dividend will differ again, depending on your positioning along other axes such as age, physical appearance, religion, gender, sexual orientation, education level and citizenship. Again, those who belong to an educated elite do not necessarily have to ‘be’ elitist; the point is that they should acknowledge and strive to be accountable to the fact that they systematically benefit from these privileges, even where they are not consciously deployed. Institutional privileges do not function in the same way for everybody.

In a spirit of friendship with the world, we must recognize one thing – a necessary and often unmanageably complex-seeming characteristic of this ‘rotten present’ – namely, that one is always multiply situated within these constellations. That one exists within an educational elite does not, for example, simply negate one’s ‘migration background’ or a childhood spent among a majority-Catholic German rural proletariat; likewise, being a lesbian does not negate one’s whiteness. In keeping with this complexity, the conversation about difference must free itself once and for all from the ‘positional fundamentalism’ that is currently spreading its reach on both the Right and the Left. The question of the inter-imbrication of divergent, often equally intimate, sometimes contradictory divisions in contemporary society must finally be brought to the centre of the discussion.

Modes of scholarship dedicated to the use and development of the Marxian concept of ‘articulation’ strike us as particularly useful here. Given the enormous wealth of theoretical literature and empirical research premised on ‘articulation’, we will only gloss the concept very summarily. The important thing to note is that what we (in the German context) would call ‘articulation theory’ deals in conditions, relations and dynamics rather than categories and group identities. It inquires above all into the contingent social production of difference, for example, via race, nation, geography or gender.

Instead of beginning with a preconstituted category of female oppression, for example, articulation theory focuses on precise historical instantiations of that relation, pinpointing specific institutions, forms of knowledge, practices and norms that produce ‘woman’ as a racialized (and heterosexualized) category. The same goes for the category ‘race’. Racism, argues race theorist Avtar Brah, ‘is neither reducible to social class or gender, nor wholly autonomous. Racisms have variable historical origins but they articulate with patriarchal class structures in specific ways under given historical conditions.’70

Articulation refers to a practice: a practice of linking two or more ‘relational figurations’, for instance, gender, class or ethnicity. It is, to be precise, a form of connection-making that does not necessarily give rise to any unity; and if it does do so, that unity needs to be understood as neither essential nor determinate nor necessary nor permanent, as Stuart Hall shows.71 Articulation denotes, then, not so much a straightforward relation between given entities as a nexus transforming the identity of the linked elements.

Articulation itself is a transformative process. For example, when they become articulated, gender and race do not remain unchanged; they are never simply added together. Our social identities are not merely the sum of the social positions to which we belong, such that one might boil oneself down to an additive equation [white + female = me]. Rather, the ‘I’ of any subject is (re)produced as white within shifting parameters of femininity and masculinity, and rendered female within shifting parameters of race, sexuality and class.

Laclau and Mouffe emphasize another dimension of articulation we’ve already touched upon, that is, the construction of ‘nodal points’. The function of nodal points is, to fix meaning, to get the incessant movement of the social to stand still, to foster new differences and call up new subjectivities. Nodal points provide us with a reality, or rather a way of seeing. It is through nodal points that realities become reality. For Fredric Jameson, the articulation ‘is thus a punctual and sometimes even ephemeral totalization, in which the planes of race, gender, class, ethnicity, and sexuality intersect to form an operative structure’.72