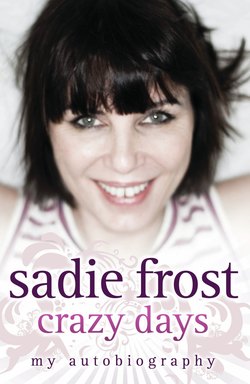

Читать книгу Sadie Frost - Crazy Days - Sadie Frost - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Mary and David Mary

ОглавлениеWith a finger, Mary wiped the bead of sweat from her forehead, tracing its journey down her temple. It was a useless task as no sooner had she brushed it away than more beads formed on her chest, her neck and even her arms. It was as if what was inside of her was pushing everything outwards. She repeated the words to herself, ‘If the contractions are two minutes apart you are entering the final stage of labo –’ She resisted the urge to shout out and forced herself to concentrate on the facts in the book, dog-eared and dirty, clutched to her chest like a bible. The childbirth manual that she’d found in a second-hand bookshop in Camden Town was her only source of knowledge. There was no one else she had been able to ask about her expanding stomach and all the complicated feelings that came with it.

After the cramping pain had subsided she tipped her head back and studied the anaemic little delivery room that they had shoved her into at the Whittington Hospital. The only sound, apart from her own breathing, was the ticking of the clock on the wall, which displayed the date in a little box within the face: 19 June 1965. So this was to be the day. She gripped the book to her breast and nursed her belly with the other hand, rubbing the material of the crème anglaise-coloured nightdress that she’d chosen with great care for the birth. She’d so desperately wanted the birth of her first baby to be special, but she was totally alone. No mother or father or sisters or friends. She’d resigned herself to that months ago. But I want him to be here. Him. Where is he? Where was he when she needed him? Even the nurses were too busy to sit and comfort her, and she felt ashamed. Of what, she didn’t know exactly.

She returned to the book and wondered if she would ever have got this far without it. All her friends back home were busy with homework or enjoying school discos. London was huge and unfriendly, and however much she adored him, he hadn’t been much help at all. A vast, shuddering pain interrupted her reading and the book slipped from her grasp as she reacted to the searing rip – as if someone was chopping her open from the inside. Her cry brought a nurse to the door, a stern woman with a time-worn face.

‘Nurse!’ said Mary, panting. ‘I think my baby’s coming.’

‘Just keep breathing, love,’ said the nurse, distracted by something that was happening outside the door. ‘We’ve just got something to deal with out here.’ And then she disappeared again. Through her pain Mary heard shouting in the corridor but instead concentrated on the cruel strip light on the ceiling as if it was a beacon showing her the way. The shouting became louder and she made out a man’s voice. She heard ‘Fuck you!’ and ‘Let me through, you bastards!’ and other swear words, but it meant nothing to her because of the pain. She couldn’t understand who was shouting and why. All she wanted right then was him beside her, holding her hand. She leaned her head to one side and a tear slipped down her cheek as she remembered the first time she’d ever set eyes on him, standing on that bridge in Ashton, over a year earlier.

She hadn’t really wanted to meet him but her mate Maureen had persuaded her.

‘Come on, Mary, what’s up with you? Don’t you want to meet a fit lad? He’s not from ’round here.’

‘Where’s he from then?’ she’d asked.

‘Ashton-under-Lyne,’ Maureen replied in a magical whisper, as if Ashton was the most exotic place in the world. Mind you, compared with Denton, where Mary had spent all her life, it was. Even a town five miles away offered excitement and new possibilities. ‘And he’s like 18 and he’s dead grown-up and he’s got this nose that’s like dead flat, like a shark. He’s been in loads of fights and he’s not like other lads round here. He’s right nice. And he knows stuff. Come on, Mary, come and meet him. He said that I could bring a friend and he’ll take us both out.’

Mary listened as she pushed her hair back into place, using the window of her parents’ sweet shop as a mirror. Maureen only wanted her to go along because she was too scared to go and meet him on her own. ‘OK then,’ she sighed, as if it were a big hardship. ‘If it makes all that much difference to you, I’ll come.’

She and Maureen were the adventurous ones at school, and Mary had always been up for a bit of excitement to ease the dull life that her parents wanted her to live. Mary dreamed of something other than the terraces of tiny, red-brick houses in Denton, a working-class hinterland a few miles from the heart of Manchester. She dreamed of anything else but her parents’ shop. Through the window she could see Tom Nolan, her father, serving a customer, his bald head shining, a healthy, sturdy man who loved his beautiful daughters. Of the three strong-willed, intelligent Nolan girls, Mary was the youngest and the most easily led. She didn’t want to work in the sweet shop or a bakery and had already got herself a part-time job as a magician’s assistant at the local theatre. At the tender age of 15 she was far too interested in the glamour of the stage and the adult world for her father’s liking.

‘Eh, brill,’ said Maureen, doing a little jump. ‘I’ll meet you tomorrow and we’ll get the bus to Ashton. We’re to meet him on the Guide Bridge at four o’ clock,’ she said, skipping off happily. Mary caught her father’s eye through the window and waved at him. For some reason, the description of the boy that Maureen had given her had piqued her interest more than usual. That night she conjured up a mental picture of him, which meant that as she approached the windy bridge the next afternoon with Maureen, she couldn’t help but be a little nervous. As they walked along, their smart, pointy shoes clacked against the pavement and their linked arms were tensed together in excitement. David stood alone on the middle of the bridge with his hands shoved in his pockets, braced against the wind, watching them. It was a chilly day, rain was drizzling and, from where Mary stood, Ashton seemed as depressing as Denton. As they got near, the boy took his hands out of his pockets, removed the cigarette from his mouth and blew smoke into their path before flicking the butt down into the river below.

‘All right?’ he said, and gave them a broad smile. ‘I’m David Vaughan. Or Dave the Rave, as people call me.’

Mary smiled cautiously and looked away. Something about him made her heart flutter. It wasn’t really the way he looked, which wasn’t exactly what she had imagined. He was dressed in tight corduroy trousers with the waist button missing, a windcheater and a shirt that was up-to-the-minute mod fashion but a bit grubby. His hair was messy and cut awkwardly around his face, which wasn’t handsome, but rather chiselled out of some rough stone and then maybe sand-blasted to leave smooth, round cheeks. His eyes seemed sad but were soft and kind at the same time and his nose – well, Maureen had got that part right. It was flat and crooked, as if it had been punched a fair few times and then some. Mary stole another look at him and summoned up the courage to speak.

‘I’m Mary. Mary Nolan.’

He wouldn’t stop looking at her for some time, and it was as if something was happening around her. Maureen chattered away happily enough as the three of them left the bridge and went to get a cup of tea, but Mary was thinking only about David. They went into a café and David entertained them both with stories of parties that he had been to, music he liked, his ideas and ambitions. He seemed to know everything and he was 18; he was so old. When Maureen went home for her tea, Mary stayed. She was too scared to look at him for too long, instead focusing on his hands, which were big and grubby with long fingernails that were full of paint. They seemed to tell a thousand stories. He told her that he was an artist. That he wanted to get out of Manchester and study at art school. He didn’t seem like any other man in the world. He had ambition. He explained to her that his mother had abandoned him when he was a baby and that his grandmother had brought him up.

‘Mum did come back once when I was about four or five,’ said David, sipping his tea, now dark with a skin that had formed in the time he’d spent chatting. ‘All I can remember is that she came back to get some clothes, she said, and I followed her up the stairs, then she came out of the room and instead of picking me up, she pushed me down the stairs and I fell. I couldn’t understand why she wanted to hurt me.’

‘At least you had your grandma to look after you,’ said Mary, trying to find a way through the pain she felt on his behalf.

‘My nan was as mad as a hatter,’ said Dave, staring deeply into his tea. ‘Instead of giving me dinner, she’d cut pictures of food out of magazines and put them on my plate.’

Mary bit her lip, trying to contain an overwhelming urge to touch him, to take away his pain. He didn’t know who his dad was, he said, and tried to not look particularly bothered about it either. But this vulnerability had made her even more attracted to him. Everything he did, whether it was stirring his tea or lighting a cigarette, was strong and certain, but his eyes told another story. David walked her to the bus stop, all the while never taking his eyes off her face.

‘I want to draw you,’ he said finally, as the bus came along.

‘Me?’ she said, staring at the pavement. ‘Why do you want to draw me?

‘Because you’re beautiful,’ he said, grabbing her face in his smoky, grubby fingers and staring even harder. As he did so her face caught the light of the streetlamp and showed off her huge, round, blue eyes – oval-shaped, elfin eyes which shone like a beacon. Eyes that might melt a thousand hearts. He let his gaze roll over her face, which to him was as pretty and delicate as any doll that could ever be crafted. He felt as if he’d seen all the girls that Manchester had to offer but Mary was something else. There was something about her petite beauty, the slim figure and doe eyes that had instantly driven him crazy. She wouldn’t have looked out of place among the models he’d seen in fancy London fashion magazines.

‘Go on then,’ she said, breaking free of his hand and mounting the bus. ‘I’ll meet you tomorrow if you like.’ As she watched him through the window, she felt butterflies and knew that she was in love.

The next day they met, and he was true to his word and had turned up with his charcoals to set about drawing her. She was impressed with his skill and tried to keep still and avoid the temptation to fiddle with her hair.

‘I’m gonna get out of here soon. I’m gonna go and live in Cornwall with other artists, then I’m gonna apply to art school in London and I want you to come away with me,’ he said in his thick north Manchester accent, and then he kissed her. They kissed for a long time with closed eyes and through the dream she brought his rugged face into view. His dusty-blond hair felt like straw but to her it was manly and impossible to resist.

Soon enough her parents started to get concerned that she was often out late and skipping her homework. One day, in the small front room of their neat, two-up two-down house, they confronted her.

‘So who is he? This new lad of yours.’ Tom stood by the window and looked out at the row of red-brick houses opposite, his blue eyes sparkling. Mary had got his eyes, and the prettiness of her mother, Betty, who sat next to her on the sofa. What she hadn’t inherited was their contentment with what they had.

‘He’s called David… Why, Dad?’

‘Because he’s standing over the road smoking,’ said Tom with a worried look at his daughter. ‘Why don’t you go and ask him to come in?’

Mary did as he said and soon David was drinking tea on their sofa, while her mum and dad stared at him.

‘So what’s your trade, lad?’ said her father after a few minutes of awkward silence.

‘I’m an artist.’

Mary winced inwardly as she knew that wasn’t the answer her father was after. She saw him bristle.

‘An artist? You need a proper job, lad.’

‘Why should I? Just so the bloody government can take it all in tax? Fuck that.’

David stood up, drained his tea and strode out of the door, leaving Mary shell-shocked and her mother twiddling her rosary and saying her Hail Marys. Her father went to the window and watched David retreat with an air of satisfaction.

‘You are not to see him again, Mary, you hear me?’ he said sternly. Tom had brought up his daughters to be spirited, taking them out on bicycles into the Pennines, but not so spirited that they disobeyed him. Mary grabbed her coat and marched towards the door. ‘Why not? Just ’cos he doesn’t have a job? That’s no reason to stop seeing someone,’ she shot back, angrily slammed the door and ran to catch up with David. Suddenly everything looked too small to Mary: her parents wanted her to be a good Catholic and go to church rather than live her life.

She continued to see David despite their disapproval, until one day Tom got the ammunition he needed to end his daughter’s relationship once and for all.

He brought it up the next day at dinnertime. She got in late and plonked herself down at the table, immediately noticing that her mother and father were not eating but staring straight at her. Tom cleared his throat.

‘This lad of yours. I told you to stop seeing him.’

‘You can’t make me stop seeing him just because you don’t like him,’ said Mary, defiantly popping a chip into her mouth which nearly fell out again as her father brought his fist down hard on the table.

‘You are to stop seeing him, because the lad is married. He’s only got a bloody wife, and she’s only got two kids by him as well.’

Mary stayed silent, looking fastidiously at the meat on her plate. She noticed that her mother, dressed neatly in a sweater and skirt, wasn’t eating either.

‘But he loves me,’ Mary said as she tried to absorb the news.

But Tom wasn’t going to back down. ‘You’re not even bloody 16 years old,’ he went on. ‘You should be concentrating on your education. You’ll stop seeing him or you’ll be sent away. You can go and live with your cousins in Torquay.’

She fled from the table to her room to cry and later on she snuck out to meet David and buried her head in his arms. It seemed as if they were the only two people in the world. She asked him about his wife, even though she didn’t care if he had a wife, or ten million children. All that mattered was the two of them.

‘I’m not with her no more,’ he explained, as Mary looked at him inquisitively. ‘It were a stupid mistake. I got married and had kids. I was too young, I’m still only 18, and I want to be with you.’

Mary looked up at him in despair. ‘They told me that if I see you again they’re going to send me away to Torquay,’ she said as she felt his strong heartbeat through his nicotine-stinking windcheater.

‘Good,’ he said defiantly. ‘Let them.’

The next week, as she was put on to a train at Manchester Piccadilly station, her mother gave her a final hug in the aisle of the carriage while Tom heaved her suitcase up on to the luggage rack. He looked at his daughter awkwardly before hugging her himself.

‘It’s for the best, love, you’ll see. Give us a ring when you get to Torquay. Your cousins will help you get some work as a waitress, OK?’

Mary nodded dutifully, hoping they didn’t look at her too closely and see what she was really thinking. As the train eased out of the station she waved one last time and then turned to watch Manchester slip away past the window. No sooner had the suburbs disappeared than the train pulled into Stockport station. Doors clanked open and new passengers bustled on board, accompanied by a burst of chilly air.

‘Come here often, love?’ said a familiar voice. David plonked himself down next to her and kissed her full on the lips. She smiled a smile of utter faith as he threw his bag on to the rack next to hers. ‘Next stop St Ives,’ he said, grinning devilishly. She didn’t understand why her parents hated him because the more powerful he seemed, the deeper she slipped into love with him. To her, David was a charming, kind, talented and exciting man. He made her life worth living.

She would soon find out that their fairy-tale elopement wasn’t going to be the idyll she had dreamed of. Once they reached St Ives, Mary phoned her parents and lied, telling them that she had arrived in Torquay safe and sound and that she would start to look for work as a waitress the next day. They didn’t need to know that in fact David had checked them into a boarding house as Mr and Mrs Vaughan and they would be living in blissful sin. Before long Mary did find herself a job as a waitress, at a seaside restaurant called the Captain’s Table. Her good looks meant people always wanted to employ her because she attracted custom in the right way. David started to paint and fit into the local artists’ community. But she soon found out that trouble had a habit of following David. He told her more about his eccentric grandmother and she got the feeling that he had been a wild kid, only saved by his talent for art and drawing, which he had been encouraged to pursue at school. His teachers had praised his talent, and for Mary it was this talent and those words ‘I want to draw you’ that gave David his charm.

It wasn’t long before their playing at Mr and Mrs in St Ives was interrupted, when Mary was spotted in the restaurant by a friend of her parents from back home in Denton. Mary knew this meant trouble and told David as much later that night, when they were in bed.

‘They’ll grass us up. I’ll have to go back to Denton. What are we going to do?’

‘Fuck ’em,’ said David in his usual careless tone. ‘We’ll just run away again.’

‘Where to?’ said Mary, having just starting to settle into life in Cornwall.

‘London, of course,’ said David, lighting a cigarette. ‘I’m bored here anyway.’

Soon enough they got the phone call from Mary’s parents telling her to leave David and come home immediately. Soon afterwards Mary and David were on the train to London.

After the picturesque, seagull-filled cobbled lanes of St Ives, getting off the train in scary, dirty London seemed as terrifying as it was exciting. In time they found a small bedsit above a shop on Tyndale Road, off Upper Street in Islington. It was September 1964 and David was full of enthusiasm, applying for a scholarship to the Slade School of Art on the advice of artists he’d met in St Ives who had seen his talent. He was accepted by the school, one of the most prestigious in the country. Mary used what little money they had from her waitressing and odd jobs to spruce up their single room. She idolised David’s style and copied the fashions and trends she saw about her on the London streets, experimenting with velvet and glitter and bits of fabric. It was the beginning of the Swinging Sixties and London was the centre of the universe. They were now bona fide grown-ups, sharing their first home together.

Soon, though, Mary missed a period. She realised that now they were going to be playing at being parents too. Not knowing what to do, and having no one to call, she’d found the self-help book on pregnancy and read it thoroughly, both scared and excited about telling David. Scared because she had realised that, along with his charm and talent, came temper and violence. The kind, lovely, handsome, rugged bloke she adored was tainted by the chaos of his strange upbringing. He was constantly getting into fights and often wouldn’t come home because he’d been in a drunken brawl and got himself arrested. By then she was scared too, because she’d cut all ties with her old world. After she hadn’t come home from St Ives, her father had told her that they were going to disown her. She couldn’t go home now, and she knew no one in London. Apart from the baby growing inside her, David was all she had. As much as she loved him, she had started to fear the stranger inside him. For all his tenderness and passion, there was a part of him that wasn’t her David.

Mary lifted her head from the pillow, disturbed by another agonising contraction. She couldn’t believe that so much had happened since that meeting on the bridge just over a year before, and now she was about to have a baby of her own. There were two or three nurses in the room, all busy staring up between her legs.

‘One more push, Mary, love! That’s it!’ one of them said and smiled at her.

All Mary could see was stars in front of her eyes as pain blurred her vision. A red mist flooded her head as blood and sweat mingled in her nose and mouth. Then suddenly she cried as she heard a high-pitched scream and her baby was plopped on to her chest.

‘It’s a girl!’ said the nurse excitedly, examining the scrawny little scrap. Mary stroked her baby and the relief from the agony brought forth more tears.

‘What are you going to call her?’ asked the nurse, cleaning the afterbirth from the puce-coloured little body. Mary stared at her child in rapture and wonder, full of the most weird feeling of belonging and peace. ‘I’m going to call her Sadie.’

The shouting in the corridor had started up again and two of the nurses left the delivery room. Mary began to recognise the man’s voice. It was David.

‘I just wanna see my fuckin’ daughter!’ he roared, then there was more scuffling.

‘You can’t go in there, sir. You’re not legally her husband. It’s against hospital rules. If you don’t leave now I’ll call the police and have you arrested,’ said the nurse.

‘I don’t care about the fuckin’ rules. I’m a bastard and so is my little girl.’

Suddenly the door to the room was flung open and David fell through it, followed by a nurse and a hospital porter who desperately tried to pull him out again. He broke free, stood up, stared at Mary and approached the bed nervously. She closed her eyes, not knowing whether to laugh or cry. She didn’t want any trouble but all the same he was all she had. As David leaned over and took a long look at his daughter, so small and perfect, his eyes hardened, making him look older than his 19 years, and he pulled back.

‘She’s not fuckin’ mine. Look at her,’ he said finally, turning away.

‘What? Course she’s yours,’ said Mary, confused. ‘Look at her again.’

David glanced once more at Sadie, who was covered in dark hair, almost black, so unlike his colouring. He just couldn’t accept that she wasn’t made in his image. This child, born of a beautiful mother, didn’t look anything like him. Baby Sadie was yellow with jaundice and she looked more like a little foreigner than he could take.

‘I don’t know who she looks like but it’s not me. She’s not mine,’ he said, walking out of the room. As he did so the nurses and the porter tried again to grab him but he shook them off. ‘It’s all right,’ he said. ‘I’m going and I won’t be back.’

He didn’t come back the next day, or over the next ten days, and the nurses, seeing Mary had no one else to care for her, let her stay as long as possible until eventually they needed the bed for someone else.

‘But where can I go? I haven’t got any money,’ Mary said as they explained that she’d have to leave the hospital. She knew she would have to go back to Tisdale Road, and on her own. As she packed her things around Sadie in a little Moses basket that the nurses had supplied, she knew she had to track David down. But first she needed clothes: she had only what she was standing in, and nothing for her baby. The hospital arranged for her to go to a charity shop for young mothers to get kitted out with second-hand babygrows. She picked out a few nice ones and, with Sadie safely installed in the basket, she boarded a number 19 bus outside the hospital.

It was 3.30 in the afternoon and the bus was crowded with schoolgirls eating crisps and swapping tales. Mary found a seat on the top deck and, with the basket on her lap, watched the chattering lasses all around her. It was strange to think that they were her age, and that just a year earlier the same preoccupations that they had, like who was kissing whom and what to wear for the school disco, had also been hers. Now she was worrying about other things, more serious things, like whether she had been abandoned by her lover and if she was alone in the world.

She entered their house and approached the bedsit fearfully, only to find that the door was locked and her key didn’t work. She sat on the stairs and waited, occasionally checking on her sleeping baby. Eventually a neighbour came in and started to climb the stairs.

‘Don’t suppose you’ve seen my Dave, have you?’ said Mary hopefully.

The neighbour stopped to get her breath and looked at her sorrowfully.

‘He moved out, love,’ said the woman. ‘But he left a forwarding address for post and that. I’ll fetch it for you, flower.’

Mary picked Sadie up and held her tightly. Her worst fears seemed to be confirmed. Didn’t Dave love her any more? She had to find him, and quickly. If she could just show him how pretty his daughter was… She made her way to the address written in scruffy handwriting on the scrap of paper: 110 Gloucester Avenue, just a few streets away. It was a room above a garage and on the other side of the road were some big, posh houses. The place was run-down, needing more than a lick of paint. She took a deep breath, picked up the Moses basket and went inside. It was ten days since Sadie had been born and she was unsure what kind of welcome she would get, but still Mary was determined to keep their little family together and make everything right with Dave.

Like the street door, the door to David’s flat was not locked, so she pushed it open. He was fast asleep in a single bed in the corner of the room. The single bed hurt her like a knife through the heart. She shut the door behind her and, taking Sadie in her arms, approached his sleeping form.

‘David, it’s us, your family. We’re back,’ she said, her heart thudding as he stirred. Instead of looking at her he simply rolled on to his other side.

‘All right,’ he said before drifting back to sleep. She breathed a sigh of relief and knew it was all going to be OK. He was just scared too, she told herself. It was all so confusing, but she hoped that before long he’d grow to love his daughter like she did.

And she was proved right, for soon things returned to the way they had been in St Ives. Now that Sadie had a more normal colour and David could see his daughter was a beautiful impish little creature, his heart melted. They got by on the few pounds that came in here and there. But, despite David’s devotion to Sadie, he remained erratic. His art kept him out until all hours, trying to make money or fighting or partying. Whatever he did, he did obsessively. To Mary’s regret, it seemed that he wasn’t able to be the David she loved all the time. There were demons inside him that she was too young to understand. He didn’t understand his demons either but now he had a new life in Camden Town, the epicentre of everything hip.

While pretending to themselves that all was well they were living separate lives, and Mary had no choice but to accept it. She missed her family back home and decided that perhaps the sight of their granddaughter would melt the ice and her parents would take her back into the fold. She convinced herself that taking Sadie and David up to Denton in a show of familial joy and harmony would make it clear to her father and mother that she was a responsible parent, not just a wayward teenager with a baby. So back up north they went, with little Sadie as a peace offering. At first things went to plan. Everyone behaved as David was offered tea and cake and Betty fussed around Mary and the baby, while Tom chatted awkwardly to the father of his granddaughter.

‘She’s beautiful,’ cooed Betty as Mary and David looked on proudly. More relatives arrived and Sadie was roundly admired.

‘She looks like a Nolan,’ said somebody. ‘A proper Nolan. She’s got the Nolan expression.’

David’s face turned cold and it was as if day had become night in his mind. His baby wasn’t a Nolan, she was a Vaughan. This family who had tried to ban him were taking ownership of the only thing he loved and he wasn’t going to stand for it. He stood up and the air about him seemed so thick with his enemies that he choked on it.

‘She doesn’t look like a fuckin’ Nolan,’ he said, grabbing a bottle of tomato ketchup that was on the table next to the food so carefully prepared to welcome him. ‘She looks like me.’ And with that he launched the bottle through the window, sending glass everywhere. He stormed out into the street and disappeared.

Inadvertently, Mary had given her parents all the fuel they needed to get her back. They swung into action, banning her from leaving the house and filing a request with a solicitor to make Mary a ward of court for her own protection. The full force of the Catholic religion was called upon too, and when the local priest appeared he was consulted in great depth. Sadie would be offered for adoption.

David was not seen again after the tomato ketchup incident. He returned to London and Mary knew that whatever happened she had to get back to him. Despite his violent outbursts, he was all she knew, and even though she was so alone, London was now her home. But more than anything, there was no way she was giving up her baby. Not ever. Soon afterwards, when Mary was back in her old bed in her old room in Denton, she decided enough was enough. So what if Vaughany was a lunatic? She and Sadie belonged with him. She got up, packed as quietly as she could, and with Sadie in her carry-cot, let herself out into the dark street.