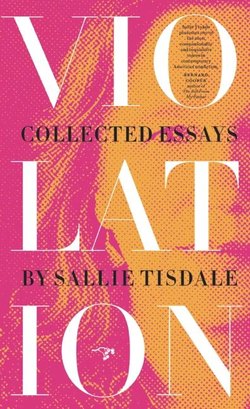

Читать книгу Violation: Collected Essays - Sallie Tisdale - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

WHEN I WAS SEVENTEEN AND A SOPHOMORE IN COLLEGE, I took any course that interested me. One semester, I signed up for Advanced Writing. (I had never taken a writing class, but I was a bit of a snob.) I bugged Dr. Ryberg constantly, haunting his office hours until he took pity, declared me his assistant, and set me to the filing. I gave him a lot of junk to read. Toward the end of the semester, I gave him a story with trembling hands. I was so proud of it; I thought it might win a few awards. He handed it back to me a few days later with entire pages crossed off in red ink. He had circled the last paragraph and written, “Start here.”

The following spring, I ran into him in the college bookstore. I was dropping out, I told him. Going north to test my theories of love and goodness.

“You’re a writer,” he said. “You’re already a better writer than me. What are you waiting for?”

I think I laughed. What an idea—that you could be a writer. But I wasn’t ready; I was consuming life like a gourmand just let out of jail. I went north and joined a communal household and a co-op and tested, with some success, several theories of love and goodness. I was still signing up for every subject that looked promising. But after a few years, when I had a new baby and hardly any money and decided at the last moment not to move into another commune in the mountains, I thought that instead I could be a writer. I hocked my piano and bought a typewriter and joined a writing support group. The leader told us to study Writer’s Market, so I sat in the reference room of the library and read about query letters and submission guidelines. I started writing essays about all kinds of things and sent them out more or less at random, with polite cover letters and self-addressed stamped envelopes.

Out they went and back they came. Sometimes there was a little note thanking me for my submission, but often not. I would type a fresh copy and send the story out again. The support group dissolved after a few months when the leader committed suicide. Others might have taken that as a sign, but I was young and ignorant and somehow immune to despair. I had decided to be a writer and so I wrote. I sent stories out, again and again. And then one didn’t come back.

The essays in this book are a selection of work spanning almost thirty years. I have never lost my fascination with the essay, and the stories here range across the continuum of the form. You don’t know what your voice sounds like until you speak. My writer’s voice chose itself. I recognize it here, but I’m not in charge. I used to wish I was a comic writer or a novelist or an investigative reporter. I tried to be a poet for a while. What I am is an essayist.

Certain themes recur as well; why should this ever surprise us? Life is just following a trail around a mountain. The path loops back to the same view time and again. Sometimes we see all the way across the plain and sometimes we’re lost in the woods, but the perspective is a little higher each time. So I return again and again to questions about the nature of the self, what it means to live in a body, why we are all lonely, how to use language to say what can’t be said. These are questions of intimacy and separation, and the answers are ambiguous at best. Long before I knew how to describe it, I liked ambivalence. Certainty has always seemed a bit dishonest to me.

Being a writer of the long personal essay is a little like being the village blacksmith. It takes decades of training, and there may not be much demand. I think I’m a good writer, but not a very good author—that is, I’m rather introverted and uncomfortable with self-promotion. As the noise level rises, I retreat a little more. Writers are increasingly expected to be multimedia performers, chasing the zeitgeist and molding their work to fit. I remember hearing the word midlist for the first time, decades ago. My editor was gently explaining her modest expectations for my book, but my first thought was, yes, that sounds about right. The midlist is disappearing now, and I could spend a few more years fretting about it. But the cure is to write.

To write—which is to say, solve the problem. I sometimes imagine the barren stretches, false starts, and breakthroughs that I experience with almost every story are kin to what any scientist or inventor feels. The essay is the problem and I seek the solution: a structure, a start, an end, a phrase. A word.

My basement is filled with failures—boxes of unfinished drafts, scribbled outlines, entire books collapsed into chaos. Countless dead ends. But it is as important for writers to fail as it is for any inventor. A year of not succeeding is a year without editors or deadlines. No other voices intrude. There is, finally, nothing to fear. If you don’t know what to do, and finally you don’t know so completely that the entire world seems to be the question—well, then anything is possible. When we don’t know the way, a thousand paths exist. All I have ever had to do to succeed as a writer was to fail, because not solving the problem means the solution lies ahead.

I write out of what really happened, a huge field in which to roam—but a bounded field nevertheless. I sometimes work with students who are struggling to write at all. I might ask them to draw a picture of their writer’s block. One young woman covered a page in black and wrote across it, “I will be found wanting and thrown out of the universe.” We are all imposters, never more so than when we try to tell the truth. To write the essay is to be haunted by our own lies. No story is the whole story. Everything we know is shadowed by what we’ve missed, forgotten, or been afraid to see. The title essay is my answer to a question that I have asked myself and been asked by others countless times: how do we know what is true? What is fair for me to say about others? What do I have the right to say, when I can never be sure about the truth?

I try to solve the problem.

Few things are worth writing down—that’s why there are so many boxes in my basement. But there is only one way to find out what those things are. Now and then, I have imagined not writing. What a different shape my life would have had. How much time! Mine has been a very indie, mezzanine, remainder table, 367-followers-on-Spotify type of career. What if I wasn’t writing or trying to write or avoiding writing all the time? What if I didn’t have this witness on my shoulder? What if I just … stopped.

Instead, I fall asleep to language bouncing around my skull. Words pour through my life like drops of water, running together into a stream, becoming—

Start here.