Читать книгу Last of the Independents - Sam Wiebe - Страница 7

II

ОглавлениеLast of the Independents

Pastor Titus Flaherty had fashionably cut hair, black with a white streak that ran temple to sideburn on his right side. His teeth were widely spaced and jutted at odd angles, and when he spoke he vivisected you with enormous, soulful John Coltrane eyes.

“Cliff Szabo is a difficult person to maintain a friendship with,” he said as we crossed the parking lot in the direction of the mission.

I drank some of my London Fog. “I’m not trying to marry into his family,” I said. “Long as he’s somewhat close to sanity, I can work with him.”

The rain had abated by the time we started back from the café. The Pastor had ordered a pumpkin soy latte and a whole grain fudge bar without a hint of shame. Vancouver. Water droplets from leaky awnings hit our shoulders as we walked along Cambie Street.

Over my shirt and jeans I was wearing a tan trench coat that had been liberated by an ex-girlfriend from the wardrobe department of a local television show. Due to a romance that ended with the girl abandoning her possessions and fleeing to the Maritimes, I’d inherited the coat of the show’s tough-as-nails, murder-solving coroner. Forget that in the real world coroners don’t usually solve murders — neither do private investigators. The coat had taken a beating over the years, and I’d lost the belt, causing it to billow out unglamorously as the Pastor and I walked into a strong wind.

“I didn’t mean to imply Cliff isn’t a good-hearted person,” Pastor Flaherty said. He rolled up his sleeve and tapped the face of a large-dialed, numberless watch that looked out of place on its simple leather band. “My father’s. When it was stolen Cliff tracked it down and paid for it out of a pawn shop window. He wouldn’t let me reimburse him.”

“Almost like giving to the poor,” I said. “If he called the cops he could’ve got it back for nothing.”

“That’s what I’m getting at. Cliff can be suspicious. Truculent. Especially with agents of authority. He will scorn your help. He will make this about anything other than the matter at hand. Just bear in mind, Michael, whatever he says comes from a man dealing with unfathomable heartbreak, pain, and guilt.”

“Guilt?”

“I’ll let him tell you, if he decides.”

The mission took up both floors of the leftmost building on a block of similar-looking grey rectangles. I stood under the canopy on a walkway of crushed stone while the Pastor went inside to find Mr. Szabo. I read the list of activity groups and meetings booked into the top-floor common room for the coming week: NarcAnon, AlAnon, Overeaters Anonymous. Coping Without a Loved One met Monday afternoons excluding holidays. I flung my tea bag into the rusted ashtray mounted by the door.

Szabo came out alone. A short man, bald, with a dark beard and thick dark eyebrows. He wore a light grey polo shirt and slate grey slacks, polished black shoes, and a cheap digital watch. He glared at me for a moment.

“Mr. Szabo,” I said. He nodded. “My name’s Michael Drayton. I’m a private investigator.”

He nodded again. We’ll see.

“I understand from Pastor Flaherty your son is missing and you’re thinking of hiring someone to look for him. I’ve a certain amount of experience in this.”

“In kidnappings?”

“Beg pardon?”

“Django James wouldn’t run away. He had to have been taken.” The earnest expression on his weathered face challenged me to disagree.

“By whom?” I asked.

“If I knew that, would we be talking?”

“How do you know?”

“I don’t know my own son?”

“You’re saying he was too obedient to run away?” I thought of adding, “Ever heard of puberty?”

“Django was waiting in the car,” he said, as if summoning every part of his will to remain calm. “When I came out of the pawn shop, the car was gone. You think I’m lying?”

“I don’t know you.”

Emphatic nods from Mr. Szabo. “Or my son. Just like the other vulture, Mr. McEachern, you don’t care. You’re here for your chance to pick the bones.”

“I don’t work like McEachern,” I said.

But he was on a roll now. “You smell blood in the water. You say you can help; only you need money first. You take the money and you ask questions. You get things wrong, you don’t listen. Then you don’t find him and you say, sorry, I have other ideas but they cost more money.”

He paused and lit an American cigarette. It smelled harsh and good in the morning air.

“Do you know what I do for a living, Mr. Drayton?”

I shook my head.

“I buy and sell. Gold, electronics, bicycles, anything. I buy for cheap, fix and clean, sell for more. I support my family on this. You think that’s easy?”

“Couldn’t be,” I said.

“Damn right. I pay attention and I have an eye for scams. I know the difference between gold and gold-plated, between an American Stratocaster and a Korean. I’ve seen every fraud. I even pulled off some, when I was younger.” He sucked on his smoke and stared at me through a yellow cloud. “But I never made money off a missing child.”

“Your mind’s made up,” I said. The cigarette smoke had awakened old urges. I downed the cold dregs of my drink and placed the cup in the ashtray.

“You people exploit grief for money. You sell false hope. I can’t believe I let Mr. McEachern convince me to trust him. You people are all smiles while the wallet is full.”

“I’ve heard about enough,” I said. “I didn’t take your kid and I’m not after your fortune. If you manage to swallow that wad of self-righteous bile lodged in your throat, you can find me in the corner office on Beckett and Hastings. Mira Das with the VPD will vouch for me.”

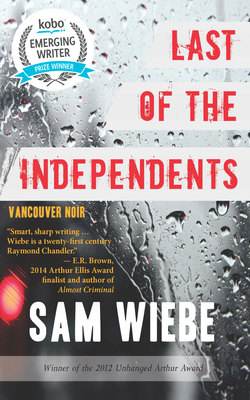

I took out one of my business cards and tried to hand it to him. He made no move to take it. I set it on the edge of the ashtray. The card gave my address and company name in bold, and in cursive the motto Last of the Independents. Katherine had insisted the old cards looked too plain. Szabo stared down at the card but didn’t move.

Before I left I added, “Whether I hear from you or not, I hope you find your son.”

I crossed the street, leaving him there, feeling bad about letting down the Pastor, but not that bad. There was nothing else to be done. Clifford Szabo needed angelic intervention, not a PI.

Instead of going to the office I went home. Self-employment has its privileges. I made a chicken sandwich and sat on the back porch, eating and reading and every so often tossing a grey tennis ball across the overgrown yard. My dog limped after the ball and dutifully retrieved it, less enthusiastic about the game than I was.

It had been two weeks since the diagnosis. Cancer of the lymph nodes. Before that she’d had laboured breathing and the odd rectal discharge. Physically, she looked deflated, as if someone had let a third of the air out of her. I had a talk with a very nice vet who recommended treatment to postpone the end. I said of course, how much? She quoted me a figure in the mid four digits. I told her I was twenty grand in debt already and was there any other option? She told me I’d have two months at best and that some time before that, “When you think it’s right,” I should make another, final appointment.

The dog had flawless bowel control before lymphoma. Now she rubbed her ass on the carpets compulsively, looking ashamed of herself as her body continued to betray her. In addition to ruining the rugs on the upstairs floor, a stool softener had to be inserted every morning. Dawn usually found me cradling her on the porch while one hand pushed a spongy red capsule of Anusol into her rectum. As vile as that chore was, I would’ve done it happily every day for the rest of my life.

“He’s right here,” my grandmother said, banging through the screen door to deposit the cordless phone into my hand.

“Drayton,” I said. My grandmother stood over me, arms crossed.

“Mr. Drayton? Gordon Laws. Talked to your secretary a couple minutes ago. Nice girl. Listen, just wanted to extend my thanks personally. My son and I, lot of water under the bridge, but on account of you we have a chance to go forward as a family. My wife is thrilled. Also wanted to tell you, check’s ready for pick up, and we decided to give you a nice little bonus.”

“That’s very generous. My assistant, Katherine, she’s the one who did the lion’s share of the work.”

“Well, make sure she hears that we’re happy.”

“Will do.”

“Take care.”

“Same to you.”

“All right.”

“All right then.”

“Christ,” I said, handing my grandmother back the phone.

“Something the matter?” she said.

“No, I just owe Ben a hundred dollars.”

She shrugged and pointed at the dog. “Looking a pretty sorry spectacle.”

“She still gets around the yard,” I said.

The only way my grandmother would coexist with a dying dog was a promise from me that once the cycle was over, I’d refinish the main floor in real hardwood. My grandfather and his brothers had built the house on Laurel Street. During renovations in the late seventies, on my grandmother’s whim, they installed pink shag carpeting in all the bedrooms. Her sinuses had had to live with that decision for almost forty years.

“You will never catch me letting someone put their hand up my bum,” my grandmother said. “I’d rather be dead than that.”

“If it was Antonio Banderas’s hand, you’d look forward to it all day.”

She scowled, shook her head, collapsed the phone’s antenna and took it back inside. I rolled the ball underhand along the shadow of the clothesline. The dog, resting on the lawn, raised her head and watched the ball roll past, as though deciding if it was worth the effort.

At the office I found Katherine and Ben in the midst of an argument over some film, Ben making the kind of sweeping statement that I doubt even he believed, but said to enrage others and make himself feel edgy.

Ben vacated my chair and moved to the other side of the table. His hands were busy slicing one of my old business cards into strips.

“How’d it go?” Katherine asked.

“Ever date someone who was on the rebound, and they try to hold against you everything their ex did to them? Well, Mr. Szabo hired Aries Investigations, and based on that, he’s decided not to pursue a relationship with us.”

“Poor guy,” she said.

“Settle this for us, okay?” Ben said to me. “Orson Welles: genius or fraud?”

“Genius,” I said, settling into my chair.

“Correct. But would you watch his movies?”

“Sure.”

“But do you watch his movies?”

“Once in a while I’ll put on Touch of Evil.” I turned to Katherine. “Why, who was he saying was better? He never makes one of those grand dismissals without an equally absurd replacement.”

“I don’t know the name,” she said. “The guy who directed Speed.”

“Not what I said, I said it was a better film than Citizen Kane.” Ben rolled the strip of cardboard into a makeshift filter and affixed it to a slim joint he produced from his pocket. I scanned my table carefully and found particles of bud, mostly stems and seeds.

“Go outside to do that.”

“Not till you hear me out on Speed,” he said. He began counting the virtues on his fingers. “It’s got at least as many fully-developed characters. It’s better paced. The effects are better. It’s got as many memorable lines of dialogue. It obeys the laws of Aristotelian unity. It’s better acted.”

“Better acted,” Katherine said. “Keanu Reeves?”

The buzzer saved me from responding. On the monitor I saw Cliff Szabo start up the steep stairs. “Troll somewhere else,” I told Ben. To Katherine I added, “The bonus for the Laws job is yours provided you pick up the check from him.”

“Why so generous?” she asked, as Ben ducked out of the room, pawing his pockets in search of his Zippo.

“You did the work.”

“That the only reason?”

“It’s not the highest paying job, I know.”

“How about fifty-fifty?”

“Where I come from we don’t turn away money.”

“You just did.”

Cliff Szabo stepped past her. Katherine shut the door as she left, shooting me a look that was equal parts “thank you” and “you’re insane.”

Szabo tested the bench before sitting down. “I overreact,” he said by way of apology.

“I’d like to help,” I said.

“I’m still not sure,” he said. “What can you do the cops can’t?”

“Nothing.”

“Nothing,” he repeated.

“That’s right. The police have resources and connections I can’t begin to compete with. They’re your best hope to get your son back. Any PI who’s not a fraud will tell you the same.”

“So why hire you?”

“Because, statistically speaking, the more people looking, the better. And because sometimes people get lucky.”

I gestured at the kettle. Szabo shook his head.

“Most missing persons the police find, or they come back on their own. Of the three I worked where that wasn’t the case, I found two. And both were due more to luck and patience than skill.”

“You said three.”

I nodded at the Loeb file on the corner of my table.

“I want you to understand,” I said. “The best I can do is work this efficiently and diligently. I can’t make your son appear. When you feel that what I’m doing isn’t helping, say so, but know going in that it’s expensive and time-consuming, and there are no guarantees.”

He stood up and walked to the table. He produced a thick roll of twenties, stretched the elastic around his wrist, and began counting out piles of five.

“You don’t have to pay up front,” I said.

He didn’t reply until there were six piles of five, fanned across the table like a poker hand.

“Six hundred is all the money I have,” he said.

We both looked at the money silently.

“I can also pay you ten percent.”

“Of what?”

“My business,” he said, his posture perfect, dignified.

I was going to object, because I didn’t want his money and because it wasn’t nearly enough. It was an insult to say anything either way. I nodded and created an empty file on the Mac.

“Tell me everything,” I said.

“Friday, March 6th was the day he went missing. I pulled Django James out of school to take with me. I had things to sell. An Ampex reel-to-reel, some coins, and a BMX bike. He was very fond of the bike. He helped me clean it, paint it, replace the chain. The previous owners hadn’t cared for it, even though it was a Schwinn Stingray, the Bicentennial model. I let Django choose the new colour. He chose blue.”

“The cleaning et cetera happened prior to that Friday?”

“Yes. We loaded the car in the morning. I sold the Ampex around ten to a music studio. Twelve hundred dollars. Cost me ten dollars fifty cents.”

“Name of the studio and address?”

“Enola Curious. Broadway near Cambie, a couple of blocks from the Skytrain station.”

“Who did you sell to?”

“Amelia Yates, she owns the studio.”

“Is that Yates with an A or Yeats with an E-A?”

“I’m not sure,” Szabo said. “She’s bought from me in the past. We finished about 10:45, then Django and I went to some coin shops Downtown, but I didn’t sell anything else.”

“Let me stop you for a second,” I said. “Why exactly did you pull your son out of class?”

“To show him.”

“Show him what, exactly?”

“How the world works.” He sat down, not on the bench, to the left of the desk in Katherine’s chair. I watched him flex his left knee several times.

“School is important, of course,” he said. “He has to get an education. But school doesn’t tell you how to make money. How to survive. They teach you Tigris and Euphrates. Tigris and Euphrates is good, but try and pay the Hydro with Tigris and Euphrates.”

“You pull him out often?”

“Once a month, usually. We go on holidays and Pro-D days as well.”

“After the coin shops?”

“Lunch,” he said. “We went to Little Mountain. He rode the bike around. He wanted to keep it. I told him we had to sell that bike, but we’d find another. Bikes are easy to find, but original BMX bikes are too valuable to keep.”

“And he was upset over this?”

“Not upset. He’s very well-behaved.”

“Disappointed? Bummed out?”

“Yes, a bit. When I went to the bike store he sat in the car.”

“What time was that?”

“One.”

“One,” I repeated, typing it into the file. “And after you sold the bike?”

“I didn’t sell it,” Mr. Szabo said. “The bike shop low-balled. Times are tough, he said. Not tough enough to give away a Stingray Bicentennial for chicken feed.”

He waved his hand in dismissal of the owner.

“After, we went to a pawn shop, and that’s where it happened: Django and I went into the store. I was talking to the owner. Django asked could he wait in the car. I gave him the keys. I made a deal with Mr. Ramsey who owns the shop. I came out and the car was gone.” Anticipating my question he said, “2:43 p.m.,” and repeated “Friday, March 6th.”

“The car was never recovered?”

“No, it wasn’t.”

“Make and model?”

“Brown Taurus wagon, 1994. Transmission not so good, few dents in the passenger’s side door. Previous owner practically gave it away.”

“What happened then?”

“I was in shock for some time. I checked my watch. I looked around to see if I had parked somewhere else and forgot. I went into the store. I told the owner and his daughter my son had been taken. They smirked like I was joking. I kept saying it until they saw I was serious. They called the police for me. I repeated to them what happened again and again. An officer named —” He dug through his wallet, shuffling through business cards and creased scraps of paper. “Sergeant Herbert Lam.” He offered me the card. I waved it away, aware of who Lam was.

“Any phone messages after?” I asked. “Any response to the news stories?”

“Someone said I should check a house on Fraser. Three tips said that, but it turned out to be the same person each time. Sergeant Lam said the woman had a problem with her neighbour and was trying to get the police to arrest her.”

“Sounds like my grandmother.”

I saved the file as Szabo-prelim.txt and sent it to the LaserJet.

“I’ll need all the missing persons data, including a full description of Django, what he was wearing, dental charts if you’ve got them, the plate and VIN numbers from the car.”

“I’ll bring them tomorrow.”

“Make it Monday,” I said. “Give me time to run some of this down.” I brought out the client and contract forms. “And I’ll need everything McEachern worked up.”

Mr. Szabo looked at the door. “I don’t have that,” he said.

“McEachern didn’t give you a copy?”

“He did, but I was angry. I threw it at him. I told you, I overreact.”

“I don’t blame you,” I said. “I’ll talk with him.”

We shook hands. On his way out Cliff Szabo turned back and said, “I love my son, Mr. Drayton.”

“Never doubted it.”

“They’ll tell you I didn’t,” he said. “I’m not good at sharing such things. But I do love him,” he reiterated, and was gone.

In my brief time on the job, I’d met few cops better than Herbert Lam. He’d been one of the legends of the VPD, up there with Kim Rossmo and Al Arsenault, Dave Dickson and Whistling Smith. Lam was probably responsible for half a dozen missing children ending up back in the arms of their loved ones. A legacy to be proud of.

One evening in July, Lam and his family were driving home from Spanish Banks. A semi-trailer crossed the median, flipping the car, killing Lam and injuring his wife and daughter. I found this out from the front desk of the Main Street station. The news floored me. I wasn’t Lam’s age and I hadn’t worked with him on the job, but I felt a sense of loss. In the movies the great detectives are obsessive geniuses. In real life, too often they’re hard-working family men and women who don’t deserve the ends they meet.

When Katherine came back at half past four I was on the phone trying to figure out who had taken over Lam’s workload. I’d negotiated through the VPD phone maze to Constable Gavin Fisk’s desk, only to get his voicemail. Fisk I knew. I’d gone through training with him. We’d once been friends.

Katherine read through the file while I waited for Fisk to pick up. He didn’t and the call went to message. “Gavin, this is Mike Drayton. Concerning the Szabo kid. You have my number.”

I hung up and tried Aries again, to no avail.

“He’s so precise about the time,” Katherine said.

“What does that tell you?”

“I guess it’s possible he looked at his watch just before he noticed Django was missing.” She studied my expression. “Is it possible he’s lying?”

“Is that ever impossible?” I hung up the phone. “Sometimes an abundance of details means you’re trying hard to convince someone something is true. More likely, though, after being grilled by the police several times, being interviewed by the press, not to mention McEachern, Szabo probably committed his best guess to memory and now repeats it as fact.”

“So what does that tell you?” Katherine countered.

“That he’s more concerned with emotional truth than empirical truth, as most of us are. Facts have to cohere into a story of some kind before we can deal with them.”

Katherine had placed an ATM envelope on the corner of the table, currency visible through the holes. “What’s that?”

“Five hundred dollars,” she said. “Half of Laws’s bonus. I couldn’t take it all once I saw how much it was.”

“It’s yours,” I said. “You earned it.”

“When I worked at White Spot, management took a portion of the tips. Take it. Or put it into the business. Upgrade some of this shitty furniture.”

I took the money. “What’s your schedule for this semester?”

“I’m yours Tuesdays and Fridays starting next week.”

“Drop out of school and come work for me.”

She laughed. “Seriously?”

“I need the help.”

“You want me to drop out and do this for the rest of my life? On what kind of wage?”

“You just got five hundred dollars.”

“Is that likely to happen again?”

“We can negotiate,” I said. “This isn’t about money, it’s about you fulfilling your calling.”

She smirked. “Which is what?”

“Every person has a purpose to serve. This —” I swept my arm majestically around the room, Charlton Heston style “— is yours.”

“And what’s your calling, Mike?”

“I’m here to make sure you don’t squander another three years on a bachelor’s degree, and then the rest of your life in government service. Smart as you are, why the fuck would you want to work for the Canadian government?”

“Money. Security. Benefits.”

“That’s the language of fear.”

“No, Mike, that’s the language of adults.”

I said, “Work here.”

She said, “I’ll think about it.”