Читать книгу The Education of an Idealist - Samantha Power, Samantha Power - Страница 12

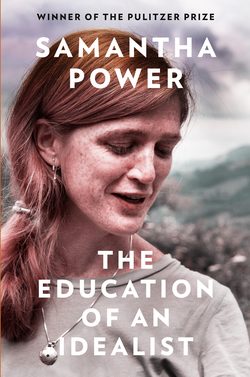

5 TANK MAN

ОглавлениеDuring the summer of 1989, I came home to Atlanta after my freshman year at Yale to intern in our local CBS affiliate’s sports department. After covering women’s basketball and volleyball for the college newspaper, I had decided to pursue a career as a sports journalist.

My print dispatches demonstrated little natural talent. My first published article in the Yale Daily News, appearing in September of 1988, had begun: “Volleyballs aren’t the only things high up in the air this week for the women’s volleyball team; so are expectations and spirits.” Another article had described how the campus a cappella group Something Extra had sung the national anthem before that weekend’s Yale–Cornell women’s basketball game. I then proceeded to observe that “the Blue were well aware that it would take ‘something extra,’ or rather, ‘something extra-ordinary’ for them to win.”

Broadcast journalism, I thought, might be a better fit. In the coming years I offered play-by-play and color commentary for the Yale men’s and women’s basketball teams and joined a rotating group of students on a nightly radio talk show called Sports Spotlight.

On June 3rd, I had been instructed by my supervisor at the Atlanta station, WAGA, to “shot-sheet”—or take notes on—a Braves baseball game against the San Francisco Giants. I had to mark down on my clipboard the precise time at which memorable events occurred—a home run, an error, an on-field brawl, a funny dance in the stands—in order to help assemble the sports highlights for the evening news. As I sat inside a glass booth, I was surrounded by other screens showing CBS video feeds from around the world.

On the feed from Beijing, where it was already the early morning of June 4th, I saw a startling scene playing out. Students in Tiananmen Square had been demonstrating for more than a month, urging the ruling Chinese Communist Party to make democratic reforms. The protesters had used Styrofoam and plaster to build a thirty-foot-high statue called the Goddess of Democracy, which bore a close resemblance to the Statue of Liberty. They had lined her up directly opposite the portrait of Mao Tse-tung, making it look as though she was staring down the founder of the repressive Chinese state. But the day I happened to be working in the video booth, the Chinese government was cracking down. I watched as the CBS camera crew on the ground filmed soldiers with assault rifles ripping apart the students’ sanctuaries. As tanks rolled toward Chinese protesters, young people used their bicycles to try to flee the scene and transport the wounded.

In the raw, unfiltered footage playing in front of me—much of which would not be broadcast—I could hear the CBS cameraperson arguing with the authorities as he was jostled. At a certain point, the monitor went black; the feed from China had been terminated. I sat in the booth, aghast at what I had seen. I found myself wondering what the US government would do in response, a question that had never before occurred to me.

That week, the front pages of all the major American newspapers printed a photograph of a man in Beijing who became known as “Tank Man.” The man wore a white shirt and dark pants, and carried a pair of plastic shopping bags. He was pictured standing in the middle of a ten-lane Chinese boulevard, stoically confronting the first tank in a column of dozens.

The stark image arrested my attention. That, I thought, was an assertion of dignity. The man was refusing to bow before the gargantuan power of the Chinese military. His quiet but powerful resistance reminded me of the images of the sanitation workers in Memphis whose strike Martin Luther King, Jr., had joined shortly before he was assassinated in 1968. They had carried signs that simply read “I AM A MAN.”

Although Tank Man’s subsequent actions received less attention, video footage showed him taking an even more remarkable risk: he climbed onto the tank’s turret and spoke with the soldiers inside. After he stepped down and the tank attempted to move past him, the man moved with it, daring the soldiers to run him over. A few minutes into this grim dance, men in civilian clothes dashed onto the road and hustled Tank Man away. The convoy barreled ahead; the man disappeared. He has never been identified. An untold number of Chinese students—likely thousands—were killed that summer in the government crackdown.

I did not respond to these events by suddenly proclaiming a newfound intention to learn Mandarin and become a human rights lawyer. But while I knew little about the protests before they started, or even about China itself, I could not shake my discomfort at having been contentedly taking notes on a Braves game while students my age were being mowed down by tanks.

For the first time, I reacted as though current events had something to do with me. I felt, in a way that I couldn’t have explained in the moment, that I had a stake in what happened to the lone man with his shopping bags.

Where did this reaction come from? Was it just the natural awakening of a political conscience—an inevitable progression after spending a year on a socially aware college campus? Maybe, but never before had I considered involving myself in the causes that consumed some of my classmates. If my political views were developing by osmosis, I had not been aware of the transformation.

My best friend from college, Miro Weinberger, happened to be visiting me in Atlanta that week. Since Mum and Eddie had moved to New York the previous fall and our Atlanta house was up for sale, I had rented a room in a shared apartment. Drinking beers on the stoop, I told my friend about the footage from China. Miro—who today is in his third term as mayor of Burlington, Vermont—was the son of anti–Vietnam War activists. Miro and I had bonded over our shared love of baseball, but unlike me, he had always been equally interested in the world around him. “What am I doing with my life?” I asked. When Miro looked puzzled, I explained, “It just feels like I should be doing something more useful than thinking about sports all the time.”

When I returned to Yale that fall, I became a history major, throwing myself into schoolwork and studying with far greater intensity than during my freshman year.

TWO MONTHS AFTER I RETURNED to campus, the Berlin Wall came down, ushering in the collapse of communist regimes across Eastern Europe. I had subscribed to USA Today, practicing what I called the “clip and shake” method—clipping the red sports section and shaking the rest of the paper into the recycling bin. Now I switched my subscription to the New York Times, eager to understand the monumental developments abroad.

The names, places, and events described in the Times were so obscure to me that I underlined key facts and figures, quizzing myself after I finished an article. With the fall of the Iron Curtain, commentators were reappraising the United Nations and wondering whether the dream of international cooperation might finally be realized. I took the train from New Haven to Manhattan for a guided group tour of UN Headquarters. I liked the concept: a single place where all the countries of the world sent representatives to try to resolve their differences without fighting.

Back at Yale, I still played sports more than I did anything else. After getting cut by the varsity basketball team, I tried my hand at every intramural sport known to humankind (from water polo and soccer to Ultimate Frisbee and touch football). Perhaps inspired by all the hours I had watched my mother play, I also picked up squash, eventually making the varsity squad. While other students received awards in a year-end ceremony, for being “Most Social” or “Most Likely to Succeed,” I was such a fierce competitor that my residential college classmates created a new category for me: “Most Likely to Come Back from the Intramural Fields with Bloody Knees.”

Nevertheless, reading the international news and taking political science and history classes had significantly broadened my interests by the time I finished my second year. Combining a gift from Mum and Eddie with money I had saved working in various restaurants, I was able to fund a summer-long trip to Europe.

John Schumann, whom I had started dating at the end of my freshman year, would be my traveling partner. Known as Schu, he had a mop of dark brown curly hair and an open and warm manner that made him a beloved figure on campus. A class above me, Schu had gone to high school in Cleveland and shared my preoccupation with sports. But unlike me, he was also a voracious reader of history, making him a ringer in Trivial Pursuit and a fascinating companion. We became so close that our identities seemed to merge into a single entity that our friends referred to as “Sam and Schu.”

The centerpiece of our trip would be newly democratic Eastern Europe, where mass protests and political transitions were capturing daily headlines in the United States. We loved the thought of exploring a part of the world that had not yet been overrun by Western tourists and where history was being made every day.

Before we departed, the always well-read Eddie thrust an article from a little-known publication called The National Interest into my hands. Authored by Francis Fukuyama, and titled “The End of History?,” the article argued that with fascism and communism soon destined to land in the dustbin of history, economic and political liberalism had won the ideological battle of the twentieth century. “The West,” Fukuyama concluded, had triumphed.

Although I vaguely recall my Irish hackles being raised by his tone toward small countries,[fn1] Fukuyama’s core claim that liberal democracy had proven the better model seemed convincing. The foreign policy commentators I had begun reading gave little hint that issues of tribe, class, religion, and race would storm back with a vengeance—starting in the Balkans, but decades later spreading to the heart of liberal democracies that had seemed largely immune.

In June of 1990, Schu and I set out to see firsthand the region where the demand for democratic accountability had helped bring an end to communist rule. But before venturing east, we traveled to Amsterdam, where we visited the Anne Frank House. I had read about the Holocaust in high school, but it was during my travels that summer that the horror of Hitler’s crimes hit me deeply. Just as observing Tank Man—a single protester—had helped me see the broader Chinese struggle for human rights, so too did visiting Anne Frank’s hiding place bring to life the enormity of the Nazi slaughter. I learned a lesson that stayed with me: concrete, lived experiences engraved themselves in my psyche far more than abstract historical events.

When I had read Anne Frank’s story the first time, I did not focus on the fact that she and her family had been deported on the last train from Holland to Auschwitz. Nor had I been aware of the stinginess of America’s refugee quotas, which prevented Anne’s father from getting the Frank family into the United States. Struck by these details in Amsterdam, I began keeping a list of the books I would read upon our return to the United States—specifically, books that focused on the question of what US officials knew about the Holocaust and what they could have done to save more Jews.

Next, Schu and I traveled to Germany, visiting the Dachau concentration camp, where Nazis had killed more than 28,000 Jews and political prisoners. The air around us felt heavy, as though the evil that had made mass murder possible still lurked nearby. Seeing the barracks, the crammed sleeping quarters, and the crematorium reduced us to silence for the first time in our relationship.

Although the museum exhibit at the camp made for an extremely bleak day of sightseeing, we lingered in the section that told the story of Dachau’s liberation by American troops in April of 1945. For all our criticisms of what the United States may have failed to do for European Jews, Schu and I wondered aloud how the modern world would look if President Roosevelt had not finally entered the war.

When we took the train to what was then Czechoslovakia, we happened to arrive just a few days before the country held its first free election. A college classmate connected us to a middle-aged woman named Tatjana who had joined the dissident movement in 1968, after Soviet-led forces crushed the Prague Spring. Tatjana invited us for tea and showed us the trove of opposition leaflets that she had circulated as a member of the underground. Then she brought us to accompany her to the neighborhood polling station. We watched as she asked her young daughter to place her first democratic ballot in the box. Tatjana choked up as she talked about the exhilaration she felt regarding her country’s political future. Again, I was struck by the importance of dignity as a historical force. “What was horrible about the communist rule,” Tatjana told us, “was that the man in front of you ordering you around was very stupid, and you had to listen to him.” Even amid jailings and torture, these smaller humiliations ground people down.

Schu and I then traveled north to Poland, which had experienced its first free election on the same day in June of 1989 as the Chinese crackdown in Tiananmen Square—a coincidence that would cause the landmark Polish vote to go almost unnoticed in the American media (a cold competition among world events that I would learn more about later on). Our most inspiring visit of the summer was to the Gdańsk Shipyard, where, in 1980, Lech Wałęsa had organized workers in a strike that would launch the Solidarity trade union. Solidarity turned into an opposition movement that eventually counted nearly a third of the country’s 35 million people among its members.

Yugoslavia, a country in southeastern Europe bordering the Adriatic Sea, was the one place that Schu and I did not warm to that summer. While we had been blessed to form new friendships in the other countries we visited, in Yugoslavia we struggled to make connections. The trains and buses were crowded and hot, and the Cyrillic alphabets in Serbia and Macedonia made finding our way more difficult. “It just seems there isn’t much laughter here,” I wrote in my journal.

Before we visited, Schu and I had thought of Yugoslavia as a single entity. But in Croatia, one of its six republics, the people we met expressed little allegiance to the confederation. Given that the country’s dictator, Josip Broz Tito, had died a decade before and that communism had now collapsed, it was not clear what or who would unite the country’s diverse inhabitants. “I wonder if the state will have a reason to exist,” I wrote to myself at the time. While fissures were evident even to an ill-informed tourist like me, I could never have imagined that the beach resorts where Schu and I swam would soon be subjected to intense bombardment by the Serb-led remnants of the Yugoslav Army. Indeed, the fall of the Iron Curtain had left us with the impression that the world was on its way to becoming more democratic, humane, and peaceful.

THE TRIP SCHU AND I TOOK to Europe cemented our relationship. But the closer we became, the more I worried about him. In the eight years since my father’s death, I had been trailed by a morbid fear that my loved ones would suddenly die. If Schu was even an hour late returning to our dorm, I was often in a full state of panic by the time he arrived.

I also began to suffer bouts of what Schu called “lungers.” Whether on campus or on our travels, every few weeks I would find myself struggling to breathe properly. I could identify nothing tangibly wrong, and I never rasped for breath or experienced asthma-like physical symptoms. I just felt, moment to moment, as though my lungs had constricted and I simply could not take in enough air.

Because I never experienced lungers when I was in a tense situation—playing for the team collegiate national championship in squash, or taking final exams, for instance—I dismissed Schu’s gentle suggestion that my breathing problems might be related to anxiety. After a few days during which I could think about little else, the feeling would usually pass. Instead of seeking professional counsel and delving more deeply into the roots of this occasional phenomenon, I began pushing away the person closest to me.

The summer after my junior year, I lived with Schu in Washington, DC, taking up an internship with the National Security Archive, a listing I came across at Yale’s career services office. As I read about the Archive, I momentarily thought it was a quasi-governmental outfit given that it shared an acronym with the National Security Agency. But far from being a cloak-and-dagger intelligence enterprise, the National Security Archive was, in fact, a progressive nongovernmental organization (NGO) whose scholars and activists spent their days submitting Freedom of Information Act requests to secure the declassification of US government records. They then used the previously classified information they unearthed to better understand US involvement in events like the 1973 coup against Salvador Allende in Chile.

The Archive’s senior researchers were skeptical about US conduct abroad and determined to hold American officials accountable by exposing their deliberations. I found it fascinating to wade through piles of declassified transcripts of government meetings and telephone calls and to study decision memos and talking points that US officials had relied on to carry out their business. Much of what I read was intensely bureaucratic. But I recognized that these sterile pages were the vehicles by which American policymakers made decisions that, in some cases, impacted the lives of millions of people.

As I grew more interested in US foreign policy, Schu was beginning to consider a career in medicine. Having been a history major at Yale, he returned after he graduated to his hometown of Cleveland to take the preparatory science classes he needed to apply to medical school. After three years together, we decided to go our separate ways, though at the time I felt sure that we would find our way back to each other.

As I looked ahead, I envied the clarity of Schu’s professional plan. He would have to break his back taking vexing science classes, but he knew the steps required to one day be able to treat patients. I was interested in trying to find a career that would allow me to work on issues related to US foreign policy. Although I would not have dared express my hopes aloud, I wanted to end up in a position to “do something” when people rose up against their repressive governments—or when children like Anne Frank found themselves dependent on the actions of strangers.

But I did not see a clear path ahead.