Читать книгу Trapped in Iran - Samieh Hezari - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE

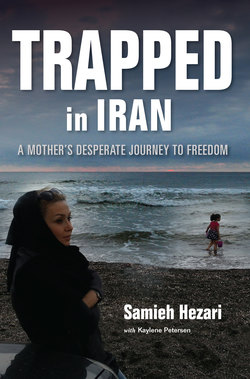

ОглавлениеFinding out that your partner wants to be with someone else is difficult. For me, at the age of thirty-four with a broken marriage behind me and now a failed two-year relationship, I struggled to cope. I was living in Dublin, where I thought my dreams had come true. In many ways, yes—Iran, where I had grown up, happy but with limited freedom after the revolution, was behind me, and I cherished the liberties of my new country. But I had grown apart from Jabbar, the husband I had left Iran with. We had filed for divorce in 2003, and the relationship I then entered into with an Irish man had also floundered. Too much Muslim for him, too little for my ex-husband. For a year I tried to pull myself together, but I found myself increasingly unable to focus on my work as a financial advisor and I had very little interest in life. I was immensely depressed, immersed in feelings of failure about who I was and where I was going. I no longer knew where I belonged: in the traditional and conservative culture my ex-husband and I had come from, or with the freer way of life I had discovered on my own in Ireland.

Lost and alone.

I didn’t know where to turn, so I did what many people do in hard times—I went back to my parents. I returned to Iran. I was granted a month’s leave from work and, with my six-year-old daughter, Saba, traveled to my homeland. She was excited at the prospect of a trip to see her grandparents. She had loved our last trip there and reveled in the attention my family lavished upon her.

It was so good to see my family again at our home in the city of Rasht, near the Caspian Sea in northwest Iran. I am the eldest of four children and the only girl. My brother Sina is two years younger than me, and I am seven years older than Salar. My youngest brother, Sasan, is sixteen years younger. I love him as if he were my own child. While I was growing up, my parents had worked long hours in their restaurant, and responsibility for Sasan had often fallen on my shoulders.

So many S names! It was traditional at the time of my birth for children to be named by the father, although these days it is usually a joint decision by both parents. It was also traditional for all of the children born to a couple to be given names starting with the same initial. This created great confusion for my madar-bozorg, my grandmother, because not only did she have to remember our four S names, but also one of my aunts had named her three daughters Susan, Simin, and Sepideh! We were always greatly amused watching Grandmother trying to remember the names of her grandchildren. She used to call out the wrong name or tell us stories about our earlier days and get our names mixed up, resulting in much laughter and cries of “That wasn’t me” or “I never did that!”

My grandmother was a beautiful woman with a wicked sense of humor. She had the brightest blue eyes I had ever seen, and I would often gaze into them longingly, silently wishing I had inherited them. She doted on me particularly, for I was always polite and respectful. I always made time to listen to the stories she told about my grandfather, my pedar-bozorg, that my brothers and cousins dismissed as boring. I could sit for hours listening to her talk about my grandfather, watching her blink back tears as she reminisced about her lost love, who died of a heart attack when I was just five. Even as a young girl, I wanted to meet a man I could love as deeply as she loved him.

I was glad I had taken the chance to come to Iran to rejuvenate in the hometown I loved. As a child, when anyone asked me where I was from, I would always grin broadly and proclaim with great pride: “I am from Rasht city!” Like Iran’s capital, Tehran, Rasht is considered a modern city. It is close to Russia, so it benefits from all the latest imports of electrical goods and furniture. Caviar production is a big industry in Rasht and it is exported all over the world—I never tried it, as it was only available in very upmarket restaurants and cafés.

Rasht is also the capital of the Gilan Province, known throughout Iran for many delicious types of rice and silver fish and the famous Lahijan tea. Iranians are big tea drinkers, and the tea from the town of Lahijan, which has a strong aroma and an even stronger taste, is a national favorite. There is nothing particularly remarkable about Rasht itself, with the exception of the huge Parke Shahr (City Park), but I loved it regardless and have many wonderful memories of growing up there. My school, Hefdahe Shahrivar or Foroogh High School, was one of the most reputable girls’ high schools in the city; year after year it achieved the highest university acceptance rate—something the school was understandably proud of.

Our family home stands right in the heart of Rasht near the food markets. When I lived there it had two big bedrooms, one belonging to my parents, where Sasan also slept, and the second shared by myself and Sina and Salar. The house had a large kitchen and a sitting room that doubled as a guest room. We knew the rules about the sitting room: do not mess it up under any circumstances, as back then people typically did not call before they visited, and my mother did not want to be embarrassed by our clutter. Over time, my father renovated our house, transforming it into three two-bedroom apartments, one of which was their modest home. My mother still took great pride in decorating. In years past, Iranian homes were furnished with Persian rugs and carpets, because people sat on the floor, but that was before my time. We did have a Persian rug in the middle of our sitting room, but that was just for decoration—we and everyone else I knew sat on a couch.

Like all the houses on our street, we had a big backyard. When we were children, my mother had been an enthusiastic gardener and our backyard was bursting with flowerpots holding geraniums, roses, and pansies. They were my mother’s pride and joy. Even now I can hear her fretful warning: “Stop running; you are going to break them!” Later, too old and tired to be gardening, she insisted on lots of artificial flowers, which did not require any attention and were strewn lovingly throughout the apartment.

My siblings and I had often asked my dad if we could move a bit farther out of town, where it was quieter and less busy, but he had inherited our house from his mother and the street held far too many memories for him to just up and leave. Despite being seventy-seven now, my father is healthy and fit. A night owl, he was always reading, and I took after him in that regard. Many people have said that I look like my dad. We have similar-shaped faces and eyes and, like me, my dad is small in stature.

Rasht is close to the Masouleh Mountains, home of the famous Masouleh step village, so called because the land is so steep that one house’s front yard is another house’s roof. Beyond that village you come to the most beautiful waterfalls. The narrow roads leading up the mountains are lined with village women dressed in traditional and colorful Gilaki tunics and scarves. Women in Iran are not allowed to show their hair and are expected to wear loose clothing in public. These women sell traditional homemade bread sweetened with honey, saffron, and vanilla and served hot. The scent is so inviting that no matter how hard I tried, I was never able to walk past the women without buying some sweet bread.

Only half an hour from Rasht lies the Caspian Sea. It stretches all along the north part of the Gilan Province and shares a border with Russia. Iranian summers are very hot, and in the summer months people flock to the beaches to cool down in the water or just sit on the sand and feel the sea breeze brush their skin.

Above all, the people of Rasht are renowned for their hospitality and love of entertaining, and my mother certainly fit this mold. Whenever we had someone come to visit, she would busy herself in the kitchen for hours, making colorful dishes that would give off the most delicious aromas.

The only thing I did not like about Rasht was the climate. It rains almost all year round and is dreadfully humid. I’m not the only person I know who sometimes took three or even four cool showers a day, as the heat and humidity make you sweat so much.

The humid climate of Rasht is particularly uncomfortable for women. Although males can wear short sleeves, by law young girls from the age of nine have to cover themselves up with long-sleeved tunics, shalwar (trousers), and roosari (scarves). When I was a child, I had constantly complained to my mother about this as I trudged around in heavy garments while my brothers ran around cool and carefree in their T-shirts.

“That is the law, Sami,” she always replied, the dutiful Shia Muslim, forever trying to raise her daughter properly.

Upon being told about this law in school I consumed myself with the injustice of it. Why should boys have the freedom to wear what they want and girls have to endure uncomfortable, heavy clothes in the hot, humid summers?

But of course there was an answer to that question. We were taught that if men see a woman’s flesh, it would make them stare and could cause “excitement.” At the time, I did not understand this “excitement.” I only knew that it was very dangerous and to be avoided at all costs.

This law about women’s clothing was one of many enforced by the Revolutionary Guards who patrolled the streets in Iranian cities. I cannot remember a time when I had not been aware of the Revolutionary Guards, even as a child. Those men and women in uniform came in after the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and still today are the military elite whose role is to protect the regime, by force if necessary. The revolution certainly brought changes, but not the kinds of changes the people I knew so desperately wanted. The wealthy took the opportunity to leave Iran, but most people did not have the money to escape and had to stay and anxiously await what the future would bring. No matter what people may have thought of the police under the regime of the shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Revolutionary Guards proved far more hostile and power-hungry. They did not tolerate resistance, and protesting against the new regime could, and often did, result in death.

The Shia clergy (Islamic priests educated in Islamic theology and law) were granted far more authority than they had ever had before, resulting in stricter rules being imposed on society. This included the way people dress, how they act, and whom they are seen with.

When I was growing up, alcohol was strictly forbidden, as was casual mingling of the sexes in public. Attending or hosting a party with both women and men and where music, dancing, and alcohol were present was considered a serious crime. If the Revolutionary Guards were not paid money to stay away—a cash payment could make a corrupt guard turn a blind eye to almost anything—they could show up unannounced and arrest people on the spot. Everyone was afraid of the Revolutionary Guards. Unless you had money or political connections, getting arrested—even for something minor such as listening to music in public—could result in a long prison stay. Sometimes women who were arrested and did not have money were given the option of having sex with a corrupt guard to avoid prison and a criminal record. A prison record almost guaranteed no chance of securing legitimate employment later on, so for many women allowing the guards to do what they wished with them was a price they paid reluctantly. Of course not all guards behaved this way, but the problem was you never knew what sort of guard was going to arrest you.

My brothers and I had little interaction with the Revolutionary Guards when we were children, as we were always with my parents, who were very careful to abide by the government’s rules and not draw attention to themselves. This changed when we became teenagers and were free to roam the city.

The Revolutionary Guards patrolled the cities in white Toyota Jeeps with a green band around it emblazoned with Ghast E Ershad, which means “Police of Islamic Guidance.” That always struck me as odd, because the Revolutionary Guards did not guide anyone—they enforced rules, and often very harshly. Even now I can recall the sheer terror that would rise in me when one of their Jeeps approached. Whoever spotted it first would call out “Gasht, Gasht!” as loudly as they could without being noticeable. Everyone would instinctively look to the ground, averting their gaze and desperately willing them to pass by without stopping to interrogate. Although the guards mostly traveled around the cities in their Jeeps, they also patrolled on foot.

One summer’s day when I was fourteen and out with my brother Sina in Parke Shahr, we were approached by a Revolutionary Guard. I remember suddenly looking up to see him standing there, his severe gaze bearing down on us. In his hand he held the standard baton wielded by all Revolutionary Guards, and his gun was clearly visible in its holster.

“What is your relationship with her?” he said to Sina harshly, nodding in my direction.

“She is my sister,” Sina replied immediately.

“Show me your ID cards,” the guard said, looking at Sina and then shifting his focus to me.

“Why do you need to see our ID cards?” I replied. “Can’t you see that we look alike?”

All Iranian citizens have to carry ID cards in case they are stopped by Revolutionary Guards, a practice that angered me even as a child. The government should not be controlling people’s lives.

The guard dismissed me by raising his voice and hitting the inside of his hand with his baton. “SHOW ME YOUR ID CARDS AT ONCE!” he barked.

I nervously dug my hands deep into my bag, searching for the ID card. Finding it, I pushed it forcefully into his open palm. As he read the card, I couldn’t help myself—I told him I would ask the next person who walked past if they thought Sina and I looked like we were related and I bet they would say yes.

Handing over his ID card, Sina glared at me. “Quiet, Sami. You can’t argue with them.”

“Don’t tell me what to do, Sina,” I snapped.

We continued to fight in front of the guard, who by now had checked our ID cards and realized we were bickering like brother and sister. He explained that he had to check ID cards because too many people were indulging in “inappropriate” relationships. I was enraged but could not say anything. Whom we chose to spend time with should be our own free choice!

My brother Salar, the most spirited of us siblings, suffered far more from the new regime during those years. Around the age of ten he started borrowing Hollywood movies from his friend for us to watch at home. Hollywood movies were illegal in Iran, but they were smuggled in, and if you knew the right person you could get hold of them relatively easily. My brothers and I loved watching the movies any chance we got. One movie was broadcast on television every Friday, but they were really old black-and-white comedies such as Laurel and Hardy and the Three Stooges, which I never found funny.

Salar, like my oldest brother, Sina, took classes in karate and loved Jackie Chan movies, so these were a prominent feature in our video-cassette player. I also remember watching Die Hard, Rocky, and The Exorcist. None of us could understand the words, because the films were in English and not subtitled, but we loved them regardless. The West was a strange, enticing world to us.

Our family looked forward to seeing which movie Salar would borrow from his friend each week. My mother always said she was too tired to watch the films, but my father would often join us. We would sit huddled around the small TV in our sitting room, stuffing our faces with nuts and sunflower seeds, my brothers carefully watching the karate moves, and me collapsing in hysterics.

Salar’s journey to his friend’s house and back usually only took about ten minutes, but one evening Salar didn’t return. We waited almost an hour until the worry got too much for us and we went out in the streets searching for him.

Eventually a man admitted he had seen Salar being dragged off by Revolutionary Guards. My dad became frightened, frantically contacting his friends and eventually managing to locate Salar. He had been beaten black and blue by the guards for being in possession of non-Islamic material. They had tied his feet together with rope and beat him with sticks. My father brought him home, and upon seeing Salar my mother and I had burst into tears. I was so angry but there was nothing I could do. Salar was in terrible pain and unable to walk for a week.

Now, many years later, on this trip back to a repressive country that was so different from my adopted Ireland, I vowed to show Saba the real, enduring beauty of the country of my birth, taking her to all the places I had loved in the cheerful innocence of childhood. Despite its current government, Iran is a beautiful country and I love every corner of it. I took her to the Lahijan Mountains and introduced her to my favorite restaurants and traditional food, like the delicious chelo kebab—the national dish of Iran—which is made with ground beef, lamb, or other meat infused with aromatic saffron and served on skewers with Persian rice.

I hired a small boat to take us out to the Anzali Swamp, which lies parallel to the Caspian Sea and is covered in water lilies. The water was so clear that we could see the fish swimming below. “Look, Mummy,” Saba squealed, pointing. My eyes followed her outstretched arm to a beautiful silver fish that glided toward us and quickly disappeared under our boat. It was such a beautiful, peaceful place, and in that moment, with my daughter so happy beside me, I was glad to have taken the chance to come back to the hometown I loved.

As I peered over the edge of the boat, I saw my reflection staring back. I almost didn’t recognize the woman who held my gaze and looked so tormented, her self-esteem in tatters. So weak, vulnerable. What had happened to the vibrant, defiant young woman who had left Iran with so many great hopes and dreams?

I dropped my hand into the water, and ripples shattered my reflection. I could not bear to look at that woman any longer.