Читать книгу First Wilderness, Revised Edition - Sam Keith - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

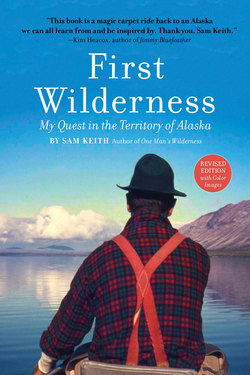

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Buried Treasure

BY BRIAN LIES

This is a book that almost didn’t happen.

Sam Keith, the author of the award-winning book One Man’s Wilderness, passed away in 2003. Four years later, his widow, Jane, moved from their retirement home in Anderson, South Carolina, back to Massachusetts, where Sam and Jane had lived for many years. Jane’s new apartment didn’t have much storage space, so during the move, a dozen archive boxes of Sam’s—filled with letters, journals, unpublished manuscripts, photographs, and slides—went instead to a garage … our garage.

You see, I’m married to his beloved daughter, Laurel.

Laurel and her father were kindred spirits. For years after his death, the boxes sat untouched on steel shelves at the back of our garage. Opening them was just too painful.

The boxes collected dust until the winter of 2013, when thoughts about their contents started to nag me—I knew there were stories in there that Sam had written, but never published. A junior-high-school English teacher for twenty-six years, he routinely came home after school, napped in his favorite chair, then wrote. He kept a journal almost every day of his life.

Sam had written One Man’s Wilderness in 1972, recounting the story of his longtime friend, Dick Proenneke, who’d chosen to build a log cabin in remote Alaska and live a subsistence lifestyle. Using interviews, notes, and Dick’s journals, Sam had written a best-seller. Now, forty years after the book’s initial release, and long after it was reissued in paperback, sales were still strong.

Standing in our garage, I looked at the shelved boxes and wondered, What if there’s another publishable manuscript in there?

Pushing past our snow thrower and Christmas decorations, I began to pull the boxes from the shelves. Inside one, I found a smaller cardboard box. On its lid were the words Raw Quest written in Sam’s distinctive handwriting. I lifted the lid to find a thick stack of onionskin paper, a typed manuscript. A quick look told me that this was Sam’s autobiographical account of his first trip to Alaska, during which he met and shared many adventures with Dick Proenneke, as well as other remarkable men whom he befriended. Wow, I thought. This could be it.

I started reading the pages, hoping that there was a real story there, rather than just journal entries. Soon I realized I was no longer reading because the author was my father-in-law, whom I’d respected and loved. I was reading because this man’s adventures in the Territory of Alaska were at turns harrowing, funny, and fascinating—a letter home from a different time, and from the one remaining wilderness in North America. I couldn’t wait to tell Laurel what I’d found.

When she read it, she discovered a facet of her father that she’d never known. Laurel agreed—this story needed to see daylight.

Sam’s life before the events in this book was already marked by adventures. He was born in Plainsfield, New Hampshire, in 1921 and raised by loving parents with his younger sister, Anna, whom he adored. Sam’s father, Merle Vincent Keith, was a talented wildlife artist who never found the success he yearned for, and who worked a variety of manual jobs to try to support his family. The family moved frequently, from New Hampshire to Massachusetts and then to Bayside, on Long Island, New York, where Merle felt his proximity to the New York publishing world would offer more opportunities for success.

But the Great Depression hit them hard, and the publishing work never materialized. The family’s financial difficulties left lasting marks on Sam—personal scars from being forced to accept government aid as a boy, and feelings of obligation to family—which stayed with him throughout his life. To the end of his days, he was extremely humble, downplaying his own skills and talents, and poking fun at his own mistakes.

Merle Keith taught Sam and Anna about hunting, nature, and outdoor skills. Nature was a release from the hardships of life, a place both real and imagined in which a person could survive and even flourish, given the right skills and mind-set. Nature was a sacred thing, to be honored and conserved. It would play an important role in his writing. He hoped one day to write a story that his father would illustrate, and the two would find success together.

On graduation from high school in 1940, Sam joined the Civilian Conservation Corps, and spent a year building fire suppression roads in Elgin, Oregon. Then he returned to Long Island to work as a landscaper before enlisting in the Marines in May 1942. He would serve as a radio gunner in the “Billy Mitchell” Marine bombing squadron the Flying Nightmares, and survive being shot down over the Pacific Ocean. Later, he was awarded several decorations for his military service.

After the war, Sam attended Cornell University on the G.I. Bill, earning a degree in English Literature in 1950. He filled countless journals with his observations about nature, people, and life—the stuff that might later become stories.

But after graduation, a sense of duty drew him back to help out at home. His mother had passed away while he was in college, and his father remarried. The household now included Merle, his new wife, Molly, and mother-in-law, Mrs. Millet. Instead of striking out and pursuing his dream, Sam took a job in a machine shop. He began to chafe. He wanted more. He needed an adventure, a purifying experience in which he could find out what he was really made of. The territory of Alaska had always called to him, and at last, he made up his mind to go.

The following adventure stories from Alaska begin in 1952, and in them you’ll meet that man in search of adventure and acceptance. You’ll read about how he met Dick Proenneke and how their lifelong friendship began. And you’ll meet a number of colorful characters who inhabited the place that would, in 1959, become the forty-ninth state.

Sam wrote this manuscript in his after-school hours of 1974. Neither his wife nor his daughter was aware that he’d written another book. In preparing it for publication, Laurel and I, working with our insightful editor, Tricia Brown, have changed as little as possible. Occasionally, we found that his letters or journal entries about a particular event were fresher or more vivid than the manuscript version and would be more interesting to a modern audience. So we’ve tucked them in. We’ve included excerpts of his letters home, shedding additional light on his thoughts or actions. And we’ve also pared away some small bits—overly long descriptions or observations—that got in the way of telling the story.

The following is Dad’s distinctive voice, already familiar to the many thousands who have read One Man’s Wilderness.

So—please meet Sam Keith, at last telling his own story, in First Wilderness.