Читать книгу Einstein Intersection - Samuel R. Delany - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

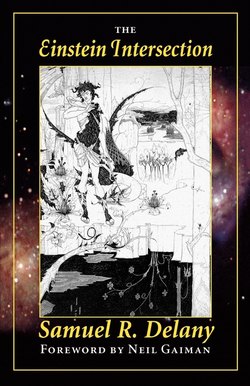

Foreword

ОглавлениеBY NEIL GAIMAN

Two misconceptions are widely held about written science fiction.

The initial misconception is that SF (at the time Delany wrote The Einstein Intersection many editors and writers were arguing that Speculative Fiction might be a better use of the initials, but that battle was lost a long time back) is about the future, that it is, fundamentally, predictive. Thus 1984 is read as Orwell’s attempt to predict the world of 1984, as Heinlein’s Revolt in 2100 is seen as an attempted prediction of life in 2100. But those who point to the rise of any version of Big Brother, or the many current incarnations of the Anti-Sex League, or the mushrooming power of Christian fundamentalism as evidence that Heinlein or Orwell was engaged in forecasting Things To Come are missing the point.

The second misconception, a kind of second-stage misconception, easy to make once one has traveled past the “SF is about predicting the future” conceit, is this: SF is about the vanished present. Specifically SF is solely about the time when it was written. Thus, Alfred Bester’s Demolished Man and Tiger! Tiger! (better known in the United States as The Stars My Destination) are about the 1950s, just as William Gibson’s Neuromancer is about the 1984 we lived through in reality. Now this is true, as far as it goes, but is no more true for SF than for any other practice of writing: our tales are always the fruit of our times. SF, as with all other art, is the product of its era, reflecting or reacting against or illuminating the prejudices, fears, and assumptions of the period in which it was written. But there is more to SF than this: one does not only read Bester to decode and reconstruct the 1950s.

What is important in good SF, and what makes SF that lasts, is how it talks to us of our present. What does it tell us now? And, even more important, what will it always tell us? For the point where SF becomes a rich and significant practice of writing is the point where it is about something bigger and more important than Zeitgeist, whether the author intended it to be or not.

The Einstein Intersection (a pulp title imposed on this book from without—Delany’s original title for it was A Fabulous, Formless Darkness) is a novel that is set in a time after the people like us have left the Earth and others have moved into our world, like squatters into a furnished house, wearing our lives and myths and dreams uncomfortably but conscientiously. As the novel progresses, Delany weaves myth, consciously and un-self-consciously: Lobey, our narrator, is Orpheus, or plays Orpheus, as other members of the cast will find themselves playing Jesus and Judas, Jean Harlow (out of Candy Darling) and Billy the Kid. They inhabit our legends awkwardly: they do not fit them.

The late Kathy Acker has discussed Orpheus at length, and Samuel R. Delany’s role as an Orphic prophet, in her introduction to the Wesleyan Press edition of Trouble on Triton. All that she said there is true, and I commend it to the reader. Delany is an Orphic bard, and The Einstein Intersection, as will become immediately apparent, is Orphic Fiction.

In the oldest versions we have of the story of Orpheus it appears to have been simply a myth of the seasons: Orpheus went into the Underworld to find his Euridice, and he brought her safely out into the light of the sun again. But we lost the happy ending a long time ago. Delany’s Lobey, however, is not simply Orpheus.

The Einstein Intersection is a brilliant book, self-consciously suspicious of its own brilliance, framing its chapters with quotes from authors ranging from Sade to Yeats (are these the owners of the house into which the squatters have moved?) and with extracts from the author’s own notebooks kept while writing the book and wandering the Greek Islands. It was written by a young author in the milieu he has described in The Motion of Light in Water and Heavenly Breakfast, his two autobiographical works, and here he is writing about music and love, growing up, and the value of stories as only a young man can.

One can see this book as a portrait of a generation that dreamed that new drugs and free sex would bring about a fresh dawn and the rise of homo superior, wandering the world of the generation before them like magical children walking through an abandoned city—through the ruins of Rome, or Athens, or New York: that the book is inhabiting and reinterpreting the myths of the people who came to be known as the hippies. But if that were all the book was, it would be a poor sort of tale, with little resonance for now. Instead, it continues to resonate.

So, having established what The Einstein Intersection is not, what is it?

I see it as an examination of myths, and of why we need them, and why we tell them, and what they do to us, whether we understand them, or not. Each generation replaces the one that came before. Each generation newly discovers the tales and truths that came before, threshes them, discovering for itself what is wheat and what is chaff, never knowing or caring or even understanding that the generation who will come after them will discover that some of their new timeless truths were little more than the vagaries of fashion.

The Einstein Intersection is a young man’s book, in every way: it is the book of a young author, and it is the story of a young man going into the big city, learning a few home truths about love, growing up, and deciding to go home (somewhat in the manner of Fritz Leiber’s protagonist from Gonna Roll the Bones, who takes the long way home, around the world).

These were the things that I learned from the book the first time I read it, as a child: I learned that writing could, in and of itself, be beautiful. I learned that sometimes what you do not understand, what remains beyond your grasp in a book, is as magical as what you can take from it. I learned that we have the right, or the obligation, to tell old stories in our own ways, because they are our stories, and they must be told.

These were the things I learned from the book when I read it again, in my late teens: I learned that my favorite SF author was black, and understood now who the various characters were based upon, and, from the extracts from the author’s notebooks, I learned that fiction was mutable—there was something dangerous and exciting about the idea that a black-haired character would gain red hair and pale skin in a second draft (I also learned there could be second drafts). I discovered that the idea of a book and the book itself were two different things. I also enjoyed and appreciated how much the author doesn’t tell you: it’s in the place that readers bring themselves to the book that the magic occurs.

I had by then begun to see The Einstein Intersection in context as part of Delany’s body of work. It would be followed by Nova and Dhalgren, each book a quantum leap in tone and ambition beyond its predecessor, each an examination of mythic structures and the nature of writing. In The Einstein Intersection we encounter ideas that could break cover as SF in a way they were only beginning to do in the real world, particularly in the portrait of the nature of sex and sexuality that the book draws for us: we are given, very literally, a third, transitional sex, just as we are given a culture ambivalently obsessed with generation.

Rereading the book recently as an adult I found it still as beautiful, still as strange; I discovered passages—particularly toward the twisty end—that had once been opaque were now quite clear. Truth to tell, I now found Lo Lobey an unconvincing heterosexual: while the book is certainly a love story, I found myself reading it as the story of Lobey’s courtship by Kid Death, and wondering about Lobey’s relationships with various other members of the cast. He is an honest narrator, reliable to a point, but he has been to the city after all, and it has left its mark on the narrative. And I found myself grateful, once again, for the brilliance of Delany and the narrative urge that drove him to write. It is good SF, and even if, as some have maintained (including, particularly, Samuel R. Delany), literary values and SF values are not necessarily the same, and the criteria—the entire critical apparatus—we use to judge them are different, this is still fine literature, for it is the skilled writing of dreams, and of stories, and of myths. That it is good SF, whatever that is, is beyond question. That it is a beautiful book, uncannily written, prefiguring much fiction that followed, and too long neglected, will be apparent to the readers who are coming to it freshly with this new edition.

I remember, as a teen, encountering Brian Aldiss’s remark on the fiction of Samuel R. Delany in his original critical history of SF, Billion Year Spree: quoting C. S. Lewis, Aldiss commented that Delany’s telling of how odd things affected odd people was an oddity too much. And that puzzled me, then and now, because I found, and still find, nothing odd or strange about Delany’s characters. They are fundamentally human; or, more to the point, they are, fundamentally, us.

And that is what fiction is for.

October 1997