Читать книгу Children of Hope - Sandra Rowoldt Shell - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

The Family Structure of the Oromo Captives

There is a general lacuna in the slave trade literature of the Horn of Africa and elsewhere in Africa relating to the family structure of those who were captured and enslaved. Fred Morton’s examination of a small body of narratives by East African child slaves offers some insights.1 The sixty-four personal first-passage narratives of the Oromo children in Children of Hope illuminate slavery and family structure as few sources have done to date. Each of the narratives opens with the child’s name, age, parents’ names, orphanhood, number of siblings, total family composition, and kinship structures.

Inevitably, all the Oromo children would experience the impact of what the economic historian Mike Davis has described as “a truly biblical conjugation of natural and man-made plagues”2 at some stage of their enslavement and to one degree or another.

For example, Bisho Jarsa, who had two brothers, was fourteen years of age when first sold into slavery. Both her parents were dead by the time she was first taken away from her own country. Her explanation of their deaths goes some way toward explaining the high rate of orphanhood among the Oromo children and their enslavement. According to Bisho’s narrative, her mother and father “both died at the same time, during the prevalence of a sickness which carried away a great many people. The cattle also died in large numbers. . . . A famine was all over the land at the time” (appendix B; narrative 48).

Bisho was captured in the middle of May 1889, when the “cruel days” (referred to by the Oromo as the bara beelaa or bâraa balliyyaa) of famine and the onset of human diseases had begun to creep in on the coattails of drought and failing crops. As early as 1888, starvation, bubonic plague, cholera, typhoid, smallpox, dysentery, and a host of other diseases had begun to make inroads. Bisho’s parents succumbed to one of these.3

As indicated in the excerpt from her narrative cited above, Bisho also alluded to the rinderpest, introduced into Ethiopia in November 1887. Some reports posit that by the time the disease had run its course, as many as 90–95 percent of the Ethiopian cattle population had succumbed to the disease (see discussion on page 27). Cattle were central to the lives and livelihood of the Oromo farmers. They were their primary source of meat and milk, oxen were essential for pulling their plows, and the size of their herds constituted an important indicator of wealth and status. Bulls in particular represented wealth and feature prominently in Oromo memorial grave art depicting the principal accomplishments of the deceased.4

Bisho was sent with a man to buy food in a neighboring county called Gobu, today the administrative center of the Goba administrative region renowned for its thriving marketplace. No sooner had they arrived than she was told that she was to be sold for corn. Given the severity of the drought, the value of all food, including corn, was hugely inflated. People were starving throughout the land. Bartering children for food became a desperate means of survival.

Family, Kinship, and Slavery

Suzanne Miers, a historian, and Igor Kopytoff, an anthropologist, suggest that Western notions of slavery—that the slave was “first and foremost a commodity, to be bought and sold and inherited”—were, at best, questionable in the context of traditional African societies. They contend that in the common “Western” image, the slave was simply chattel possessed totally by another, with no control over his own life or destiny. This chattel status allowed the slave to be inherited, transferred, or sold at will. Ill-treatment, even to the point of death, was legal. Slave status was intergenerational; slaves occupied the lowest rung of the social ladder and stayed there.5 Miers and Kopytoff emphasize the need to consider the influence of “rights-in-persons” within African social and kinship relationships. These rights, which Miers and Kopytoff aver are “usually mutual but seldom equal,” are present in virtually every social relationship. In terms of these rights, children can expect to be cared for and protected by their parents, husbands have certain rights over their wives, and parents have rights over their children.6 Transactions in terms of these rights-in-persons, say Miers and Kopytoff, are fundamental to African kinship and marriage systems and distinguish African from other slave systems.

The analyses of the data documenting the composition of the children’s families and the conditions of their enslavement suggest a reexamination of the concepts of kinship and slavery in the context of this study. Paul Bohannan, an anthropologist, suggests that in precolonial Africa, slave owners exchanged slaves for other slaves, never for money. In his article on the Tiv people of Nigeria, Bohannan emphasizes the unique exchangeable values of rights in human beings, particularly of dependent women and children, expressed in terms of kinship and marriage.7 This notion is consistent with the Africanist suggestion that owners did not buy slaves in precolonial Africa for money, but rather incorporated them into their families. On the other hand, Ned Alpers, a historian focusing on the political economy of the Indian Ocean slave trade, alludes to Yao male relatives selling their children “for what was very likely the simple acquisition of trading goods.”8 According to Richard Allen, a historian of the slave trade of the Indian Ocean, the sale of children by their parents or relatives was a “common mechanism” in southern Asia. The catalyst for such sales was often indigence or want in the wake of droughts, floods, and other natural calamities. “Human life,” Allen writes, “became exceedingly cheap during these periods of severe economic hardship.”9 Families selling their children is neither a new nor an uncommon phenomenon.

Within kin groups, where “rights-in-persons” prevail across a range of relationships, the acquisition or absorption of kin could be used to increase the size of a kin group and thereby to augment a kin group’s influence, wealth, and power.10 Miers and Kopytoff describe the concept of the “slavery-to-kinship” continuum wherein the status of slave and kin member merge and where neat definitions become blurred and slavery itself becomes ambiguous. Kin, in Africa, whether adopted, dependent, client, or slave, stood side by side and could meld and merge in the way that tenants, serfs, and slaves did in feudal Europe.11 The most marginalized in African societies could occupy a form of chattel status, but the chattel nonetheless remained along a “continuum of marginality whose progressive reduction led in the direction of quasi kinship and, finally, kinship.” The overlap and blending of slavery and kinship, in the view of Miers and Kopytoff, occurs in the latter portion of the continuum, “and it is here that the redefinitions of relationships we have described took place.”12 They believe that the singular stamp of African “slavery” is the existence of this slavery-to-kinship continuum.

Much of what Miers and Kopytoff address applies to the Oromo family structure. For example, the Oromo have a long-established tradition of adoption, or guddifachaa. Mekuria Bulcha, in dealing with the centrality of the Oromo kinship system to Oromo history and sociology, confirms what Miers and Kopytoff claim, explaining the guddifachaa as a system through which the Oromo could adopt individuals who would thereafter be regarded as members of the household’s putative descent group, or gosa. Further, through gosa membership, they were integrated into the larger collective of the community and, ultimately, of the nation.13 Guddifachaa not only accords with Miers and Kopytoff’s concept, but the practice goes further, penetrating the realm of the wider Oromo society.

Ayalew Duressa, a social anthropologist, observes that most scholars have ascribed the practice of guddifachaa among the Oromo to their love of children, maintenance of the family line, and as a means of acquiring labor power and access to an economic resource at both household and community levels. He notes further that some historians consider it a mechanism used by the Oromo people to incorporate (or assimilate) non-Oromo ethnic groups in the vicinity or as a means of alliance creation. However, few such studies have taken into account the influences of kinship, the economy of the people, family size, and household structure on its practice—nor, conversely, the impact that guddifachaa might have had on these issues.14 One such study is that of Dessalegn Negeri, an Oromo social work scholar, who has also explored the societal impact of the guddifachaa system among the Oromo, noting, inter alia, its role in the creation of social bonds and building up resources where additional children were regarded as potential material assets.15 The Oromo sociocultural system of guddifachaa has its roots in the Oromo gadaa system of democratic governance and, as such, both endorses and transcends the individual Oromo family structure, impacting and shaping Oromo society at community and national levels.

Evidence emerging from the narratives of the Oromo children suggests substantive deviations from the kinship continuum model as well as from either the Bohannan or the Africanist notion of internal African slavery as outlined above. Nor can the guddifachaa system incorporate the diverse experiences of many if not most of the children in the group.

These considerations of family incorporation are key as we explore the age and family structure of the Oromo children.

Age Structure

As with the differential in the sex ratio between the Atlantic and the Horn of Africa slave trade,16 age is particularly significant in any study of the local slave trade (see the full discussion of the sex ratio of the Oromo children on page 209–210). Unlike the Atlantic trade from West Africa to the North American, Brazilian, or Caribbean territories, the most sought-after slaves were not young men intended directly for the plantation. Mekuria Bulcha, alluding to the reports of nineteenth-century travelers, maintains that the majority of captives exported across the Red Sea were young girls between the ages of seven and fourteen years, with a general ratio of two females to one male. There were virtually no slaves over thirty years old.17 Bulcha underscores this point further, using data derived from observations made at the ports of Massawa and Tadjoura, by stating that “a large proportion of captives exported from the Red Sea ports during the nineteenth-century were children and adolescents. Young girls between the ages of seven and 14 years represented the largest group.” He goes on to cite figures given by Belgian diplomat Edouard Blondeel van Cuelebroeck in the report of his sojourn in Ethiopia between 1840 and 1842. According to Bulcha, Blondeel quoted official figures that excluded numbers gained through smuggling, reflecting that about “600 captives, mainly Oromo, including 300 girls (most 12 or 13 years old), 200 boys and 100 eunuchs were exported from Massawa in 1839.”18 In the Horn of Africa, the trade was manifestly a trade in children.

When the missionaries and their Afaan Oromoo–speaking colleagues interviewed the Oromo children at Sheikh Othman, not all of the children were able to tell the missionaries their date of birth. Instead, the missionaries had to rely on visual observation, physical attributes (including height and developmental level), and the knowledge and assumptions of the children and their peers. The missionaries accordingly assigned each child an approximate age at the time of their interviews in 1890.

The following box and whisker plots (graph 2.1) show the different age ranges of the boys and girls. The chart demonstrates that the boys were generally younger than the girls with an age range of 10 to 18 years, a mean age of 14.33 years, and a median of 14 years. Ten-year-old Katshi Wolamo was the youngest in the group. Six boys were age 18 when interviewed.

The girls, on the other hand, were overall about a year older than the boys. Their ages ranged from 11 to 19 years, with a slightly higher average age of 14.73 years and a median age of 15 years.

GRAPH 2.1. Ages of boys and girls when interviewed (source: Sandra Rowoldt Shell).

The children’s narratives both confirm the general consensus on the youthfulness of the slave trade in the Horn of Africa and provide the sort of specific age detail not found elsewhere. To know what the children experienced in respect to the family-slavery continuum, we must first know more about the family structure.

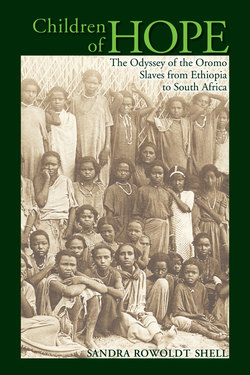

The Oromo children were well documented in photographs. From this view of the children at the mission house in Sheikh Othman (see fig. 2.1), there can be no doubt as to their young ages. Half the girls (pictured on the upper floor) can barely peek over a standard balcony railing. Below them, the majority of the boys range from waist to shoulder height of the adult accompanying them—a portrait of mass vulnerability.

Family Composition

The travelers’ accounts of this area and era indicate that youth characterizes the export slave trade of the Red Sea region. This was primarily a trade in children—and of Oromo children in particular. This meant that the tender years of this group of Oromo children undoubtedly contributed to their vulnerability. But there were other factors impinging on their personal security as well. For example, Fred Morton, in his exploration of the narratives of thirty-nine East African slave children, found that most had been separated from their parents by the time they were taken captive.19 How does this compare with the Oromo families in the present study? Did the Oromo child have the protection of a secure family environment?

FIGURE 2.1. Oromo children shortly after their arrival at the Keith-Falconer Mission (source: Acc. 10023/417 [packet 3], Foreign Mission Records of the Church of Scotland, World Mission, National Library of Scotland).

A solid 15.1 percent of the Oromo children were sold into slavery by members of their families or by neighbors. Of these, slightly more than half (53.8 percent) were paternal, maternal, or full orphans. As has been evident from the experiences recounted above, the children’s narratives reflect that when one or both parents of a child or children died, it was not uncommon for an uncle or other relative to step in to take over the late parent’s (or parents’) children and property as part of the guddifachaa system. Despite this initial gesture of kinship solidarity and sense of familial responsibility, these relatives often sold the child to a slave trader. Timothy Fernyhough, an economic historian, suggests some mitigating factors. Extreme poverty and crime, suggests Fernyhough, could result in a drop in social status to servitude, while natural disasters like drought and famine led to tougher times for those who lived off the land (see graph 2.2). This in turn led to an increase in enslavement as families found they could no longer survive independently. In these circumstances, wrote Fernyhough, “the famished offered their offspring to merchants who would feed them.”20

It would be natural to assume from this that the pressures on parents, relatives, and neighbors to sell the children entrusted to their care for gain would have increased incrementally as the effects of what is known as Ethiopia’s great drought and famine began to take hold in the southwestern regions after the summer rains failed in 1887.21

Fernyhough confirms the peak period of the famine as being 1890–1891, a year or two after the liberation of the Oromo children. Further, a cross-tabulation of the instances where a relative or neighbor sold a child indicates that more than two-thirds (69.2 percent) of the children who were sold were among those rescued off the Osprey in September 1888 when the drought and famine had begun to take their toll but had not yet peaked.

GRAPH 2.2. Years of capture showing onset of drought, famine, and rinderpest (source: Sandra Rowoldt Shell).

Only 30.8 percent of the children were from the later dhows. This second tranche of children were rescued and liberated in the summer of 1889, by which time the drought and famine had the territories to the south and southwest of Ethiopia firmly in its grip. The chart above (see graph 2.2) depicts the years in which the children were enslaved, the dates of their liberation, and the relative concurrence of external factors such as the drought, famine, and rinderpest. The bulk of the kinship sales, then, were in the early days of the drought and famine and cannot have been a precipitating cause for any reversal of the Oromo adoption system.

For example, Hawe Sukute was one of the children who had been rescued and liberated aboard the HMS Osprey. When her parents both died, she and her two brothers went to stay with their maternal uncle. However, another uncle, this time on her father’s side, “claimed them as his property and took them to his house where they worked for him” (appendix B; narrative 56). As Miers and Kopytoff point out, it was not simply a matter of a relative taking initial responsibility for the children—effectively adopting them—when they were orphaned or when the family had fallen on hard times. What happened thereafter was significant, shifting the focus away from the mode of kin acquisition to mundane and pecuniary outcomes.22 Hawe reported that her paternal uncle was in debt to the Garjeja king, so he sold her to pay the debt. Here, familial solidarity did not hold sway.

Other Osprey children experienced the profound trauma of being “disposed of” by relatives, sometimes by their own fathers. Liban Bultum’s (see appendix B; narrative 27) father was clearly wealthy, owning a large piece of land, a number of oxen, sheep, and goats, and two horses. So Liban was perplexed and distressed to discover that when a group of Sidama came to collect their tribute money, his father inexplicably refused to pay what he owed. Instead, his father, Bultum, stood by while the Sidama seized his son in lieu of the tribute debt, carrying him off to a nearby slave market and selling him to the “Nagadi,” a group of established slave traders and merchants.

While “Sidama” could refer to the neighboring people in the area south of old Abyssinia, the term is more likely to refer to the Abyssinians. In later life, Liban Bultum returned to the newly constituted and expanded Ethiopia and assisted missionary and lexicologist Edwin C. Foot in the compilation of the second Afaan Oromoo–English/English–Afaan Oromoo dictionary ever published. Given Liban’s own identification of the Sidama as “Abyssinian” in his dictionary (indicating he was only too aware of their identity), it would seem inappropriate to assume that the people who seized him in lieu of taxes were the neighboring southern Sidama people—who were as vulnerable as the Oromo: “They [the Sidama] share many similarities in terms of language, culture, values, and psychological make-up with their Cushitic neighbors. They also share the common history of conquest by the army of Menelik of Shawa in the late nineteenth-century which is by far the most critical and perverse event in Sidama history.”23

Not only family members took advantage of the more vulnerable of the children. Fayissa Murki (see appendix B; narrative 14), another child rescued off the later dhows, started off in a normal and secure family environment, living with his parents and two sisters. His father owned a small piece of land, about twenty head of cattle, and some goats in the village of Alle in the country of Danno. However, this familial stability was nonetheless fragile. While playing near his home one afternoon, a neighbor approached and asked Fayissa to accompany him to his home nearby. Fayissa complied, but once there, he must have been terrified when the neighbor detained him in his house. That night, the neighbor took Fayissa to a nearby slave market and sold him to a group of Atari merchants, who, in turn, took him to a place called Dalotti in Tigre country, where he became entrapped in the remorseless slave traffic destined for the Red Sea ports. We can presume the neighbor knew that the newly enslaved person would never be seen again.

Establishing household size, including the average family size among the general Oromo population in 1888 or 1889, is a challenging task, and estimates of the average number of children per family in sub-Saharan Africa during precolonial times have a broad range. Economic historian Gwyn Campbell, in his article on the precolonial historical demography of Madagascar, cites an average of “between 4.9 and 5.25 children per household estimated for sub-Saharan Africa in general during pre-colonial and recent times.”24 While scholars like Elisée Reclus have provided approximate population totals for the region in general and for the Oromo population in particular for 1885 (see map 1.2 and discussion on page 19),25 detailed demographic data for the Oromo in the late nineteenth century are elusive. Geographer R. T. Jackson, in his research on the influence of population size on market size and density in southern Ethiopia, estimated an average family size of five among the inhabitants of this region bordering present-day Oromia.26 This figure at least gives a rough yardstick by which to suggest a regional estimate of trends relating to family size. The average number of children per Oromo family in this study is snugly commensurate with this figure.

GRAPH 2.3. Family sizes of boys and girls (source: Sandra Rowoldt Shell).

The histogram above shows the family sizes of all the Oromo children (see graph 2.3). Gender differences in family size patterns were minor.27 Most of the boys and girls (80.2 percent) lived in families of between three and nine family members. A small proportion of children (3.5 percent) either had no memory of any other family members (Gilo Kashe, Faraja Jimma, and Galgalli Shangalla; see appendix B; narratives 19, 12, and 54, respectively) or were full orphans with no siblings (Meshinge Salban and Isho Karabe; see appendix B; narratives 59 and 23, respectively). These are included as single-member families.

At the upper end of the scale, 15.1 percent of the children had families of between ten and fourteen family members. However, even the Oromo families with larger than the average number of siblings in the home did not provide the sort of protection to an individual child that might have been imagined. Safety in numbers carried little weight against the forces that were driving the internal and export slave trade.

Orphanhood

UNICEF defines an orphan as “a child who has lost one or both parents,” so those Oromo children who lost either their father or their mother were ranked as orphans.28 Nearly one-fifth (19.77 percent) of the children (11.63 percent girls and 8.14 percent boys) either could not remember one or both of their parents or did not mention them in giving details of their family composition. These figures tell their own story. Of the majority 81.2 percent who could supply these details, as many as 12.8 percent of the children were full or double orphans when they were captured—with boys accounting for 3.5 percent of that total and girls nearly three times that proportion at 9.3 percent.29

These figures compare negatively when ranked against comparable statistics from twenty-first-century Ethiopia, Oromia, or even South Africa, where the death toll of men and women between the ages of nineteen and forty-four—many of them victims of the massive HIV/AIDS pandemic—is distressingly high. Graph 2.4 shows the clear discrepancy between the percentage of orphans among our group of Oromo children and the prevalence of orphanhood in any of the regions selected for comparative purposes.

A total of 12.8 percent of the Oromo slave children were full orphans, 17.4 percent were paternal orphans, and 1.2 percent were maternal orphans. In aggregate, 31.4 percent of the children had lost either one or both parents. This figure falls just short of three times the aggregated national Ethiopian orphan prevalence percentage of 11.9 percent in 2005, more than three times the aggregated national Ethiopian orphanhood total in 2007, and 3.27 times the aggregated orphanhood total in Oromia in the same year. The prevalence of orphanhood among the sixty-four Oromo children is therefore significantly higher than might be anticipated.30

Fred Morton believes that the deaths or absence of the parents of the East African slave children of his study certainly rendered them unprotected and at greater risk.31 Raiders probably regarded orphaned Oromo children as easier quarry without the usual protection of a full family-unit complement. They may also have regarded orphans as generally more acquiescent and less likely to run away, given that they had no families to which they could return.

Orphanhood in Ethiopia is an old and still-growing phenomenon. Laura Camfield, a social anthropologist, has written recently that parental mortality, more specifically maternal mortality, is increasing in Ethiopia. She ascribes this not only to the growth in the incidence of HIV/AIDS, but also to high maternal mortality, acute illness, and the effects of drought, famine, displacement, migration, and conflict.32 The conditions experienced by the Oromo children in the late 1880s were not dissimilar—acute illness, drought, famine, displacement, migration, and conflict.

Of the fifty children rescued aboard the Osprey in September 1888, 28.4 percent were orphans. This figure contrasts starkly with the 47.4 percent of orphans aboard the dhows who were rescued and liberated eleven months later on 5 August 1889. While it is not possible to draw a straight line of causality, the considerably higher prevalence of parental mortality in the later, non-Osprey group could be considered consistent with the increased impact of the drought and famine by the end of 1888.

GRAPH 2.4. Orphanhood of the Oromo children vs. children in South Africa, Ethiopia, and Oromia (source: Sandra Rowoldt Shell).

Were children also at risk if they lived with their mother but there was no father in the household? According to Abbi Kedir and Lul Admasachew, “There is a great degree of stigma attached to children who are raised without a father figure” in Ethiopia.33 Without the paterfamilias, the children were clearly vulnerable. There was only one example of maternal orphanhood. That all other Oromo orphans were paternal or full suggests the significance of the presence of the father for the protection of the family. Nearly one-fifth (17.4 percent) of all the Oromo children were paternal orphans, a total that was distributed more or less evenly between the boys (8.1 percent) and the girls (9.3 percent). Male relatives (uncles and elder brothers) were again quick to intervene following the deaths of the fathers of six of these paternal orphans, five boys (Badassa Nonno, Bayan Liliso, Fayissa Umbe, Rufo Gangila, and Wakinne Nagesso) and one girl (Galani Warabu). (See appendix B; narratives 5, 9, 15, 32, 39, and 53, respectively.) The intentions of these appear to have been relatively benign, in most cases assuming the care of the family and working the properties. Galani Warabu’s uncle laid claim to all the family’s assets, that is, all his brother’s cattle and property, and took care of the family until the Sidama (i.e., Abyssinians) raided the country, killing the two eldest of Galani’s five brothers. Galani and her sisters successfully evaded capture by hiding from the Sidama, and, after the raiders left, the siblings returned home. Their restored sense of security was short-lived. Soon after their return, a “cousin” came to visit and took Galani back to his home. However, one day she told him she wanted to go home, prompting him to take her to the market in Macharro, situated in West Hararge in the modern Oromia region, where he sold her to a group of slave traders.

Fayissi Gemo (see appendix B; narrative 52), who was a young girl approximately twelve years of age when captured, was the daughter of Gemo and Yarachi. Gemo, her father, had been a secure landowner in a village called Upa in the Kaffa country. He owned several oxen, sheep, and goats, but he had died before Fayissi was abducted. After her father’s death, Yarachi supported the family, employing laborers to plow the land. However, the family was no longer secure. While Yarachi was away visiting her homeland, the chief of their village of Upa took the opportunity to abduct Fayissi—and promptly sold her to some passing merchants, leaving her mother and sisters behind.

Jifari Roba (see appendix B; narrative 57) was a little Oromo girl of about eleven when she was sold into slavery. Her father, Roba, her mother, Dongoshe, and her three brothers and four sisters lived in Galani, a village in the Sayo country. When Roba died, Dongoshe sought work reaping for others in the fields. In what seemed to be a compassionate gesture, a neighbor offered to look after Jifari. Immediately after taking Jifari into her home, the woman sold her to a passing group of “Nagadi” (slave traders) for ten pieces of salt (amole).

The only maternal orphan, a young boy named Galgal Dikko, was very young when he left home but was nonetheless able to remember that his mother (Hudo) was dead and that he had five brothers and one sister. He recalled:

A party of men on horseback, with guns, coming down upon his village, and, after a fierce fight, carrying himself and one of his brothers away. He became very ill as they were taking him away, and he was left by them on the wayside, near a place called Gobbu. Here he was found by a man who took him to his house. The chief of the country hearing the circumstances of this man’s finding Galgal, claimed him as his property, and promised to allow him to return to his own country when he grew up. (appendix B; narrative 17)

However, during another battle the Sidama (Abyssinians) raided the village and seized all the guns they could find. Galgal thought he was safe, but the Sidama soon returned, this time seeking slaves rather than guns, and they carried him off to a place called Tibbe, in modern Oromia.

One family member selling another is widely regarded as repugnant. One of the most familiar instances is the biblical story of Joseph.34 This practice has a long history and universality. That it was practiced in Ethiopia should therefore come as no surprise.

Given the exceptionally high prevalence of orphanhood, the incidence of parental mortality seems to have played a role in leaving the children more vulnerable than if both parents had been alive and present at the time of enslavement. From the evidence of the children’s narratives, there is a sense that the loss of a parent was likely to trigger the intervention of relatives or neighbors. In terms of the assumption of family incorporation held by African historian Suzanne Miers and anthropologist Igor Kopytoff, this intervention should have led to a continuance of familial protection as a manifestation of the kinship continuum.35 The reality, regrettably, was that these children found themselves caught in the slave trade sweep to the Red Sea coast, often directly through the actions of their kin. Whatever it meant to some, familial incorporation did not protect all the children.

Only the broadest brushstrokes have depicted what is known about the slaves and their family backgrounds in the Red Sea slave trade. Contemporary accounts and later scholarly studies of the trade concur that this was a trade in children. The Oromo children’s narratives ipso facto support this interpretation but also provide much more intimate detail. Details of Oromo family structure and kinship patterns emerge that both partially align with and significantly depart from the concept of the slavery-to-kinship continuum espoused by Miers and Kopytoff. On the one hand, there were well-established Oromo traditions of familial solidarity, namely the Oromo adoption (or guddifachaa) system. In the Miers and Kopytoff model, kin would be expected to assume responsibility for a deceased relative’s children. One cannot know about the “good” relatives, who may have looked after their wards and kept them from the slave trade. However, on the other hand, we know from the children that relatives sold many of the Oromo children to slave traders. Such sales for monetary gain or barter diverged from that kinship model. Some of these sales may be regarded as distressed sales, resulting from the drought and famine of 1887–1892. But such sales also occurred before the “cruel days” had fully caught hold. Notable among the new information emanating from the narratives was the high proportion of orphans among children traded as slaves. Orphans were potentially easier targets than those embedded in secure, full family units. Paternal orphans were perhaps the most vulnerable. Orphans could be expected to be more docile and acquiescent slaves as they had a lower motivation for escape without a family to return to. One may also speculate that orphans made perfect candidates for what psychologists have termed the Stockholm syndrome. These new considerations suggest new avenues for exploration in this underresearched area of the African slave trade.