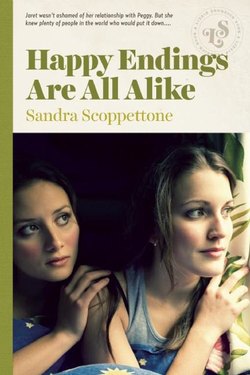

Читать книгу Happy Endings Are All Alike - Sandra Scoppettone - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Peggy Danziger’s mother was dead. She had died in December, three days before Christmas. Dr. Thomas Danziger, Peggy’s father, refused to go to the funeral and locked himself in his room for nine days. On the tenth his sister, Paula, sat in the hall on the floor for two and a half hours and talked to him through the closed door. Finally he came out, looking terrible. He had a scraggly beard and he hadn’t bathed or changed his clothes, so you could smell him when he walked by. Paula led him into the bathroom, stripped him down to his shorts, turned on the shower and ordered him into it, closing the door behind her. When he emerged from the bathroom he was shaved, dressed in a neat, clean outfit and, though he’d lost weight, he was still rather round. From then on he made an effort, although anyone who looked closely could see that a light had gone out of his eyes.

Claire had never gotten along with her mother, but often said she had “great respect for her even though I cannot agree with her ideologically.” When Mrs. Danziger died Claire was in her junior year at college. She insisted on leaving school until Peggy graduated, even though her father could easily have afforded a housekeeper. And even though Peggy was almost eighteen.

Claire had a dim view of herself. She was very intelligent but she was definitely not pretty. She had been a shock to friends and relatives, particularly when they saw her beside Peggy. They would say things like:

“Oh, what a beautiful little girl you are, Peggy. Just look at that gorgeous blond hair and those big green eyes.” Then: “And this must be Claire.”

The truth was that Claire was quite homely. But not in her mother’s eyes. Never. And she always tried to make Claire feel lovely. Claire, not buying the “inner beauty” pitch, resented her mother for the effort and for her own good looks. It was a world where “pretty” counted; in commercials, print ads, the movies, television, looks were everything. And no matter what her mother, the Women’s Movement, or Ms.magazine told her, Claire still felt homely and hopeless. No man, she was convinced, would ever want her, and although she believed that there were other things in life, having love, husband, children, was tops in her book.

Her parents tried to explain that what came from inside her was what kept boys and men away, not how she looked. She did not believe them. So when her mother died Claire took the opportunity to be mistress of a household. She would have nine months of running the house on Prospect Street, of being in charge, playing Mother, even Wife. She might never have the chance again and she’d be damned if she’d miss it!

Peggy and her mother had been extremely close, adoring each other, enjoying the same things. People seeing them together often thought they were sisters. They exchanged ideas, gossiped, laughed. When Erica died Peggy was struck numb. And then she developed mononucleosis. Everyone said it was psychosomatic. Even so, the tests said she had it and she had to stay home from school. Claire was elated.

“You see, Daddy, you see. It’s a good thing I left school. I would have had to anyway, wouldn’t I?”

“Yes, Claire.”

“I mean, who would take care of her if I were at school? I ask you, who would be here to take care of her if I hadn’t left school? I was right all along, wasn’t I?”

“Yes, Claire.”

Peggy was depressed by her mother’s absence and Claire’s presence. If Claire hadn’t been there Peggy felt she probably would have been able to deal with her grief. But Claire wouldn’t allow it.

“Come on now, upward and onward. You can’t sulk forever.”

“I’m not sulking, Claire.”

“Well, we can’t have depression. Put a smile on that pretty face.”

“I don’t feel like smiling.”

“Well, why not?”

“My mother died.”

“Oh, honestly.”

When Peggy became ill in February, Claire changed her tactics, but not for the better.

“Now you just take it easy, Baby, and I’ll take care of everything. I’m not going to let anything happen to my pretty, precious baby sister.”

“Nothing is going to happen, Claire. I just have to rest and I’ll get rid of this gazinga.”

“I’ll just plump up these pillows for you, Baby, and make the darling more comfy.”

“The pillows are fine.”

“Would you like some juice, honey? Got to drink your juice, you know.”

“I don’t have to push fluids, Claire—this isn’t a cold or a flu.”

“How about some nice hot tea?”

“How about shutting up?”

“You little ingrate.”

When Bianca Chambers first suggested bringing Jaret Tyler over, Peggy said no.

Bianca threw back her head and spread her arms as though nailed to a cross. “But why not, my dar-ling? Why not, I ask? Jaret is a fun person. Why do you persist in this way? It cuts me to the quick.”

“I’m sorry about your quick but I just don’t like her.”

“You’ll be the death of me,” she said and threw herself into a wing chair, moving it at least three inches. Bianca was very big, almost six feet tall, and her body was literally shaped like a pear. The worst thing was that her head was much too small for her body, so she’d taken to wearing her frizzy light-brown hair au naturel, which meant that it stood straight out at all angles. But at least it gave the impression that her head matched her body. She had a very nice face: beautiful blue eyes and a good straight nose. Perfect for film, she often said. Bianca intended to be an actress and to this end she directed everything.

“Pourquoi? Tell your dearest friend why you don’t like this person.”

“She gives me a pain in the gazinga.”

“You sound like an illiterate. Do you know you use that word for everything?” Bianca shoved a cigarette in her black holder.

“It’s a good word.”

“It tells me ab-so-lute-ly nothing.”

Absently, Peggy started braiding her hair. “You remember when you tried to get us together about three years ago? Well, it didn’t work.”

“Jaret was a child then—we all were, my dear. Now we’ve matured, become . . . WOMEN.”

“I guess,” Peggy said. “But why is it I feel like a kid most of the time?”

“That’s because you’re sick and full of burning.”

“What burning?”

“Never mind. Back to our little problem. You see, my dear,” Bianca said, letting the smoke trail from her nostrils, “the whole thing is simply too weird for words. You are my best friend, yes, cherie? And Jaret is also my best friend. So why wouldn’t you naturally adore one another? It stands to reason, yes?”

“It stands to reason, no.”

“But why not?” Bianca asked, one arm bent at the elbow, the hand flung out.

“Well, for one thing she runs around with that humungus crowd, and our crowd’s, you know, very low profile.”

“So low you can barely see it. I suppose what you mean by ‘our crowd’ is you, me, Mary Lou and Betsy?”

“And what’s wrong with that? Who says you have to go around in packs of hundreds?”

“Hundreds?”

“Well, that Murchison-Auerbacher crowd seems like they have hundreds.” Peggy let the braid unravel. When she had first gone to Gardener’s Point High she had wanted to be a part of that crowd, but it hadn’t worked out. Peggy found them silly, immature, and they didn’t take to her either. She had naturally gravitated toward girls with more interests and ideas. “They’re too heavy for me.”

“Jaret doesn’t like them much either, dear heart.”

“Then why does she hang out with them?”

“Nobody else to hang out with. After all, what was she supposed to do when the big crowd from last year graduated?”

Most of Jaret’s friends had been a year ahead of her and when they graduated she was left behind. Then when school started again, and Ann Murchison and Nancy Auerbacher invited her to a party, she began to go around with them.

“Well, I don’t know, Bianca. She just turns me off. I’m not into all that stuff, you know.”

“And what, dear heart, do you mean?” She stubbed out her cigarette, ceremoniously blew the last puff of smoke from her holder and dropped it into her shirt pocket.

“Dope and booze and stuff.”

Bianca gave a long trilling laugh as though she were practicing scales. “Don’t make me laugh.”

“Seems I already did.”

“Jaret doesn’t even smoke cigarettes.” She punctuated this with a bob of her head.

“I still don’t dig her.”

Bianca rose grandly, swept around the room, gesturing wildly. “All right, all right, say no more. I will not bring her here. She’ll be relieved.”

“What do you mean?” Peggy narrowed her eyes, insulted.

“Well, if you must have the truth she had no desire to come. She feels the same way about you but she was going to do it as a favor to me.”

“Well,” Peggy said, scrunching up on the couch where a makeshift bed was arranged, “what a humungus nerve!”

“You are simply absurd. Why on earth do you care?” Bianca returned to the chair, trying for an elegant position: one arm over the back of the wing, legs crossed, work-booted foot dangling.

“You see, that’s just what I thought. Jaret Tyler thinks she’s queen of the gazinga or something.”

“No, she doesn’t. She thinks you think you are.”

“Me?”

“That is correct.”

“Me?” Peggy said again, appalled. “I’m the most down-to-earth person you’d ever want to meet.”

“Well, so is Jaret.”

“I’ll bet!”

“You want to?” Bianca patted her frizz.

“Want to what?”

“Bet.”

“What are you talking about?”

“You know, sometimes I doubt that high I.Q. of yours. Would you like to bet that you find Jaret Tyler a very down-to-earth, fabulous person?”

“How much?”

“A Cher record.”

“I hate Cher, Bianca. I think she’s revolting.”

“Yes, I know. You can choose who you want. I suppose you want the Beatles. So ancient.”

“I have all their records. You can buy me a book when I win. The complete Edna St. Vincent Millay.”

Bianca grinned.

“What’s so funny?”

“She’s Jaret’s favorite poet too. You have a lot in common, Peggy. You’ll see.”

“I’ll see nothing.”

“Oh, you are trying. Anyway, I won’t be able to come around as much after Monday, you know, so it would be practical to like her.”

“I guess I’m supposed to ask what happens on Monday, huh?”

Bianca looked hurt. “You’ve forgotten. Oh well, I suppose you have other things on your mind. We begin rehearsals for The Little Foxes. I’m playing Regina, of course.”

“Of course.” Peggy kidded Bianca about her acting but she also admired her and thought she was very good.

“I must fly now, dear girl. Tomorrow I’ll return with Jaret and you will owe me a Cher record. You’ll adore each other. You’ll see. Ta-ta.”

Bianca won her Cher record. Within ten minutes Jaret and Peggy were laughing and talking. It was true. They had many, many things in common. They were so enjoying each other, in fact, that Bianca, who sat silent on the other side of the room, experienced a momentary twinge of jealousy. But then she realized she was pleased that her two dearest friends in the world would now be best friends themselves.