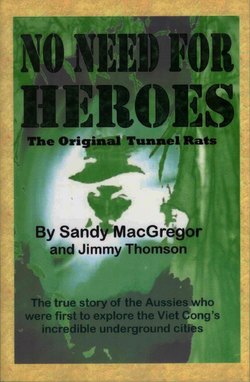

Читать книгу No Need for Heroes - Sandy MacGregor - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеIt is well that war is so terrible;

else we would grow too fond of it.

General Robert E Lee

It's not that I always wanted to be a soldier, it's more that I never thought I would ever be anything else. And the day I was awarded a rifle for being the top Army Cadet at my school, was the greatest of my 14yearold life. It did not set my life on the course it later followed, it merely confirmed in my young mind that the Army would want me as much as I wanted it.

Three years later, when I joined the army, I chose the engineers. Or maybe they chose me. For I was drawn to them by a fascination for these men who live double lives. They are soldiers in the sense that they carry arms and know how to use them. But they are much more than that: they create as well as destroy and engineers are everywhere.

Ubique, – means everywhere, and is our official motto; Facimus et Frangimus – "We make and we break" – is our preferred slogan.

Like other soldiers, engineers can kill and they can die. But when the killing stops, they pick up their tools and work. Engineers have no time to be heroes, they're too busy for that.

But comes the hour, comes the man. And if you must have heroics, try crawling through a tunnel that's too narrow to turn around in, when the only sound is your own heartbeat pounding in your ears, not knowing if the next corner will bring you face to face with any one of a dozen kinds of death. Try to imagine feeling around in a rice bag for the slender length of fishing line that is attached to a pin, which is attached to a bomb which someone has put there with the sole intention of killing you and your mates.

It's a different kind of death that you face as a sapper, and it's one you cannot turn and run from, or hide until it goes away. It is your ingenuity against your enemy's, your brain willing your fingers not to fumble, your pores not to sweat, your heart to slow down.

P/A

The unofficial badge of the Royal Australian Engineers.

It's time it was official – most soldiers believe

it expresses best what we do.

And if you get it wrong you're just as dead as if you'd charged into a hundred blazing guns.

Every soldier thinks his regiment is special, but engineers, or sappers as they're known, have qualities no others possess. When, like other soldiers, they lay down their arms at the end of their patrol, engineers pick up their tools and build and dig and create and repair. What's more, the work engineers do in peacetime is often the same as what they do at war.

They are different. They are special.

And I'm going to take that one stage further and say that the engineers of 3 Field Troop, the first unit of Australian Engineers to serve in Vietnam – and the only one on "our" side made up entirely of regular volunteers – had different qualities again. Better? Perhaps. Special? Of that there is no doubt. All conscripts that went to Vietnam volunteered. The difference was we didn't have conscripts or national servicemen, and the other troops of regulars weren't volunteers.

I came away from Vietnam with a Military Cross, one of Australia's highest honours, as reward for what we achieved there. But more valuable than that, I returned home with memories of a small slice of history: a time when ordinary Aussie blokes became extraordinary; when boys became men; when those I led became leaders themselves.

Like so many other Australians, I wear my medals on Anzac Day with pride, but perhaps the greatest honour I've ever had was to be chosen to lead the first Tunnel Rats – the men of 3 Field Troop.

I suppose we were the right men in the right place. But at the time it seemed nothing could have been further from the truth. On the other hand, there's nowhere I would rather have been ...

* * *

I am from a military family – the Army was my history and my destiny. I was born in 1940 in India when my father was in the Indian Army. I guess when he gave me his name, Alexander Hugh, he also passed on a taste for life in uniform.

Dad had joined the British Army Engineers as a bugle boy when he was 15, then went back and forth between India and England until he finally returned to spend his last days of service under Indian colours. Dad was a fantastic sportsman representing the army in India in every major sport.

I don't remember my grandparents at all, but both my grandfathers were in the Army. My mother's father was a major in the British Army and Dad's father, Christopher Duncan MacGregor, was in the Corps of Engineers.

I wish I had known him because the family stories about him were fantastic. He served in India and under Kitchener in Omdurman and Khartoum. He was also very inventive and, as is so often the case with Army Engineers, made a considerable mark without any great credit.

Apparently, on one of Kitchener's operations they needed a moveable heavy gun, so he invented a mortar mounted on a trailer – the first of its kind in the world.

Another idea of his, back in 191418, was barrage balloons, big balloons full of hydrogen on the end of long ropes or wires. They were put up above cities in the First World War so that Zeppelins and lowflying planes would be blown up if they hit them. They were used even more in the Second World War, so much so that they are almost a symbol of London during the Battle of Britain.

He was also a very good shot with a rifle and was the champion shot of all India. One year, in the AllIndia combined services shoot, he was doing much better than anyone else on a very windy day. Two Navy officers came up behind Grandad and they could see him fiddling around with the rear sight of his Lee Enfield rifle.

They asked him what he was doing and he showed them the adjustable back sight he had made for himself. The homemade sight not only compensated for distance, but moved from side to side so he could adjust for the wind.

Before too long every 303 rifle in the British forces was fitted with this adjustable sight to aim off for wind – with the patent owned by the two naval officers.

My father rose through the ranks and reached Major by the time the war ended and India gained her independence. He wrote back to his brother Bob in England to ask what conditions were like there. The news was not good. Uncle Bob reported back that the UK hadn't much to offer at the time – and especially not for children – but Australia looked like the land of milk and honey and he strongly recommended that Dad should bring us here.

So, trading on his organisational experience, he took a job running the stores for International Canners in Ulverstone in Tasmania. He later moved on to a better job with Australian Pulp and Paper Mills in Burnie.

It must have been March, 1948, when we first set foot in Australia, because I had just turned eight. It was an exciting time for me and a challenging period for my father as this was his first ever civilian job. But it must have been a real culture shock for my Mum.

My mother, Beryl, was nine years younger than Dad so she can barely have been 30 when she arrived in Australia. But it wasn't just a change of country for her, it was a complete change of lifestyle. As an Army daughter then Army wife, she would have been used to a different kind of life to her contemporaries anyway. But having spent most of her married life in India, at a time when Army life represented the last remnants of the Raj, the change could not have been greater.

Living as an officer and a gentleman in India was a very, very privileged existence. We must have had four or five servants, including a cook, an ayah to look after the children, a gardener and a bearer who was in charge of all the others. So Mum's life in India was one of not having to do any work whatsoever, apart from looking after us. When we left India, my sister Margaret was 5 and my brother Chris was 3.

So when Mum arrived in this new country – in both senses of the phrase – if she knew how to sew it would only be because she'd been taught at school. If she knew how to cook it was still something she hadn't done for 10 years. In short, she went from being a rather pampered Memsahib to being a housewife with 3 kids, and with no friends to offer advice or support.

I can say all that with the benefit of hindsight, but at the time it was fine for us kids. And despite the dramatic changes in lifestyle, it was a loving household. Mum and Dad were always there when we needed them.

I went to school in Ulverstone and Devonport. I was a member of the Cadets at both schools and it was in my last year in Ulverstone that I won the award for being the Most Efficient Cadet. My name should still be on the honour board, the second one down. My prize was a .22 automatic rifle, which, apart from being my first military honour, was very useful for rabbits.

But despite the family history and my own penchant for soldiering, the idea of a military career was never pushed down my throat. My father encouraged education in general, and he realised I had an aptitude for building work. So, if my father didn't try to push me towards the Army, he definitely encouraged me in engineering.

It was only as a result of being in Cadets that I found out I was naturally good at that stuff. Then the local Regular Army Warrant Officer said that he'd like me to look at a film on Duntroon, the Royal Military College which was in Canberra. I was so impressed I applied to go there, went through the selection board and was told that I'd passed, subject to my matriculation exam results.

I studied flat out for my exams and, realising I only needed to pass three subjects out of the four, I concentrated on the easiest three (for me) and got them. A few weeks before my 17th birthday, I left Tasmania for the Royal Military College, Duntroon, in Canberra, to begin my life in the Army.

It was only much later that I discovered how pleased and proud Dad was that I had chosen a career in the Engineers. But he had made a point of not pushing me toward a military career because he wanted me to have as many choices as possible. He was the fairest man I have ever known.

Four years at Duntroon – learning to be a soldier as well as an engineer – was the equivalent of the first two years at university. Six of us passed our exams to go on to get engineering degrees at university and I remember thinking how much easier it was at Sydney University.

For a start, the discipline was comparatively nonexistent, and there were women. But the biggest thrill for me was realising that I wasn't a dummy. I had always been in a class with three really bright guys, who would leave the rest of us struggling in their wake. When we got to university I realised that, yes, they were a lot smarter than me, but I was a lot smarter than many of the other students too.

My self-esteem increased quite a bit as a result of passing my exams and realising that ultimately these other three, Rayner, Fisher and Gordon, were really bright. In fact, John Gordon was the top student at the University of New South Wales and Gary Rayner won the University Medal at Sydney.

I met my first wife Bev at the graduation ceremony at Duntroon, when she was there with another bloke. We met again at another party after that, and we started going out about six months later.

Bev was my first girlfriend. We didn't have much to do with girls while we were at Duntroon, and to be honest I didn't know much about them. We got engaged when I was at university and got married in January 1963, a month after I got my final results from Sydney Uni.

P/B

The official Royal Australian Engineers hat badge.

Then I went to the School of Military Engineering for a sixmonth course and got my first posting into 17 Construction Squadron. By the end of that year we were in Papua New Guinea and I – a bright eyed young lieutenant – was literally up to my neck in it.

17 Construction's base was at Wewak and the squadron was there to build a road to Lumi. I was a lieutenant in charge of 10 Troop, a unit of about 40 men. Everyone else was sent forward into the jungle, but we stayed back at base.

The troop's main task was to maintain the road, but they also had a major project at Wom Point Bridge. A point of interest is that this is where Lt-Gen Hatazo Adachi of the Japanese Army surrendered in the Second World War by handing over his sword to Maj-Gen H Robertson of the 6th Australian Division – I have a photo of the obelisk erected to commemorate this.

Indonesian incursions into East Timor and western New Guinea were raising fears that Jakarta might not be satisfied with what is now Irian Jaya, and try to take the whole of the island. It was decided to extend the airport at Wewak, making it a major air base from which to fight off any invasion that might ensue.

It was fundamentally a civil engineering job. We had the men and the equipment but we lacked a basic necessity: huge amounts of gravel. However, it just so happened that Wom Point – a virtual mountain of the stuff was only a short way offshore. My task was to pull down the old bridge, which had fallen into disrepair, build a new one across to the point and make a road through the swamp so that trucks could take the gravel to the airport.

The whole operation meant living on the beach and working in swamp often up to our waists. It was tough, difficult and demanding. But it was fantastic, just to be working as an engineer. It was here that the Engineers of the Strategic Reserve – 21 Construction Regiment came to do their 14 day camp and complete the building of the bridge.

Later on I had to take some of the troop to Vanimo, near the northern border with Irian Jaya, to build a 300 tonne shipping wharf. It was great.

Now, I would be the first to admit that's not as exciting as men in balaclavas abseiling from helicopters and crashing through windows. It's not as glamorous as jumping out of aeroplanes with a parachute and landing behind enemy lines. But in peacetime, the SAS spend a lot of time and expend a lot of energy chasing their own shadows. And there are no enemy lines for paratroopers to land behind – just a theoretical front in a hypothetical battle.

Even though this was essentially peacetime, what my men and I were doing, was real. Firing blanks is a bit like playing soldiers, but a bridge is still a bridge. That's one of the things that makes sappers special.

Another is that they may be a little bit smarter than your average footsloggers. There are many reasons why young men volunteer to join the armed forces. It could be the opportunity to travel, the appeal of comradeship or perhaps a simple lack of options; the army being preferable to the dole. In my case, I came from a family with a long military tradition. The Army was a serious career option and, in fact, was the only thing I wanted to do. But for a young man who's never going to rise above buck private, it's a shortterm solution with few longterm benefits.

Unless he's a sapper.

Anyone who joined the Engineers did so knowing they were going to learn a trade or perfect a skill they already possessed. They could have been carpenters, plumbers, truck drivers or electricians. It didn't matter – they would all have something that would stand them in good stead when they left the forces. There isn't much demand for tank drivers and artillery gunners in civvy street. So maybe that spark of ambition, that practical streak, is another vital element in the sapper's makeup.

Whatever the reason, I was glad to be able to command them in peace time, and, when it came, seized the chance to lead them to war.