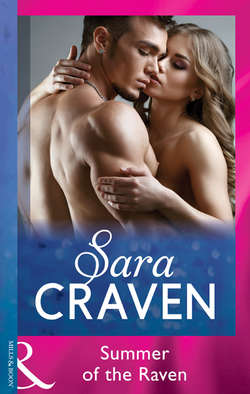

Читать книгу Summer Of The Raven - Сара Крейвен, Sara Craven - Страница 5

CHAPTER ONE

ОглавлениеROWAN transferred the weight of the shopping bag wearily to her other hand, and paused to catch her breath before mounting the remaining stairs to the flat. Just for a moment, she thought nostalgically of the lift which had operated so smoothly between floors in the previous luxury block they had lived in, but it was the only thing she did regret. She had never liked that flat, and never regarded it as home. Now, as she looked around her at the chipped paint and peeling wallpaper, then down at the worn lino covering the stairs, her lips twitched in spite of herself.

‘So this is home?’ she asked herself with a kind of desperate gaiety.

And the answer to that was – yes. It was the only home she had now. The cottage in Surrey which contained all her happiest memories had been sold to buy the Knightsbridge flat, and now that had gone too.

She sighed and hoped very much that Antonia would have a cup of coffee at least waiting for her, but it was doubtful in the extreme. Antonia had spent most of her life in an environment where cups of coffee and meals appeared as long as there was a service bell within convenient reach. Antonia had been born to be a rich man’s wife, and Rowan’s father, Victor Winslow, had filled the bill admirably as a doting and indulgent husband.

Rowan had always taken the background of money very much for granted too, until two years ago when the plane that was carrying her father to New York had crashed without survivors, and a series of long and ultimately embarrassing interviews with solicitors and accountants had revealed how very little money there was after all.

There was some money left in trust for Rowan when she was twenty-one from her late mother’s estate, and there was a small income for Antonia and herself, dependent on certain conditions. And the main one was that she and Antonia should live under the same roof until she, Rowan, was twenty-one or until she married, or Antonia married again, whichever came first.

It wasn’t a condition which had held much appeal for either of them and Rowan had been quite willing to renounce her allowance and seek her independence, but when she had suggested this, Antonia had become almost hysterical.

Before she had married Victor Winslow, Antonia had enjoyed a marginally successful career as an actress. She’d done some television work and a few minor stage roles – it was at an after-the-show party that she had met Rowan’s father – and Rowan had assumed that Antonia would resume her career. But this, she soon discovered, was the last thing her stepmother had in mind. At thirty-seven, Antonia Winslow was an outstandingly beautiful woman with auburn hair and enormous violet eyes. She could have knocked half a dozen years or more off her age without causing anyone to raise a sceptical eyebrow. But the life of a pampered wife of a tycoon suited her far better than the rat-race of acting. Antonia had no wish to have to sell herself in the market place all over again. She was quite content to accept the allowance, and Rowan was made to see that any attempt to carve out a life for herself and thus deprive both of them of this income would be arrant selfishness.

‘Your father obviously wanted you to stay in my care,’ she had declared tearfully. ‘They were his last wishes, Rowan, and you can’t ignore them. Even you wouldn’t be so heartless.’

Rowan accepted the implication that she was a cold fish without comment. There was, she supposed, a certain amount of truth in what Antonia had said, but what she could not understand was why her father had imposed such a condition, knowing as he must have done that all too often a state of armed neutrality existed between his second wife and his daughter.

When he had married Antonia, Rowan had been twelve, a slender gawky girl with her light brown hair, pale skin and wide hazel eyes. She had a brace on her front teeth and she bit her nails, and no one could have described her as a pretty child.

Antonia could possibly have enjoyed a pretty child, someone to dress up and take around with her, and reflect her own charms, although there would probably have been friction of a different kind in the years ahead. There was no friction with Rowan of this nature. If Antonia had ever asked ‘Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the fairest of them all?’ the mirror would have given her the answer she wanted.

But from the first, she simply hadn’t been interested in Rowan, and had made it perfectly plain, and Rowan had looked back at her with clear scornful eyes that seemed to see that beneath the expensive clothes and flawless complexion there was a mean, rather spoiled little mind.

Now, at nineteen, Rowan was a little more tolerant. She had few illusions about her stepmother. She recognised that Antonia was lazy and selfish, and lived consistently beyond both their means, but at the same time there could be a curiously helpless and childlike quality about her.

Antonia, Rowan thought cynically, always has to have someone to look after her. First it was Daddy, and now it’s me, and I have to do it for Daddy’s sake. It wasn’t, she realised, that Victor Winslow wanted her to remain in Antonia’s care for a few more years. It was the other way round, and it came to her rather sadly, that in his own way Victor Winslow had also been rather selfish.

She had managed a little independence for herself. She had been forced to abandon her ‘A’ level course at boarding school, because the money that was available wouldn’t cover the remaining fees, but she had enrolled at a local college of further education and was in the throes of a two-year course there. If she was successful, it had occurred to her that she might try for a degree on the Social Sciences side at one of the Polytechnics.

Life was by no means perfect, but there seemed to be a certain order and pattern emerging from the frank chaos that her father’s sudden death had left. Money was always in short supply, largely thanks to Antonia’s ideas of budgeting. This was why Rowan did the shopping herself now, on the way home from her classes. She did a lot of the cleaning too, and most of the cooking, and tried to fit her studies in as best she could.

Every so often, Antonia would bestir herself and announce that she was going to get a job. She had done a little demonstrating at various exhibitions, and some clothes modelling in the restaurant of a West End department store, relying heavily for these breaks on contacts she had known in her acting days, but she was not reliable and the offers of work were rarely repeated.

She had even managed at one stage to become a partner in a boutique which was about to open. Rowan had been frankly appalled. Where, she had wanted to know heatedly, had Antonia got the money to invest in this chancy venture? Boutiques came and went like April showers, and often their erstwhile owners found themselves facing the Official Receiver.

But Antonia had waved her objections irritably aside. They had backers, she said, people who were not afraid to risk their money on possible success. She was so evasive on the subject that Rowan guessed this unknown backer had to be a man, but she was neither shocked nor disturbed by the knowledge. Her father had been dead for two years now, and Antonia was a man’s woman in every sense of the word.

Rowan herself was still thin rather than fashionably slender, and her brown hair remained as straight as rainwater, and about as interesting, she thought detachedly. Her teeth were straight now, but she still bit her nails on occasion. The chances, she decided objectively, of her getting married before she was twenty-one were remote in the extreme. Her only hope was that Antonia would beat her to it, preferably with someone who could keep her in the style to which she had been accustomed.

This mysterious backer, whoever he was, seemed hopeful. And he must have money to burn if he was prepared to risk it on the prospect of Antonia undergoing some kind of sea-change into a successful businesswoman.

She had waited resignedly for the inevitable crash. Neither Antonia nor her partner, another ex-actress called Alix Clayton, had any real working knowledge of the exigencies of the rag trade. They assumed blandly that they would get by because of their eye for style and colour, and that their friends would flock to support them. As it was, they lasted a bare three months before the sad ‘Closing Down Sale’ notices went up in the window, alongside the announcement that the lease was available again.

Rowan had wondered uneasily how much liability Antonia would have to bear for the failure of the business, but nothing had ever been mentioned on this score. The boyfriend, she decided drily, must be besotted as well as rich if he was prepared to write off that kind of loss. Or maybe he was doing it for tax reasons.

Anyway, Rowan thought as she pushed her key into the door, she’d heard nothing more on the subject, and at least Antonia had been fairly subdued since, with no more wildcat schemes for making her fortune in the offing.

The air in the small living room was thick with cigarette smoke when she entered, and Antonia was lying on the sofa in the act of lighting another from the previous butt.

‘Chain smoking, yet?’ Rowan dumped the heavy shopping bag down on the table.

Antonia surveyed it sourly. ‘What have you got there?’

‘Nothing very exciting,’ Rowan said lightly. She ticked the items off on her fingers. ‘Mince, stewing steak, carrots, onions, potatoes, spring greens …’

‘God!’ Antonia shuddered. ‘You should get a job catering for some kind of works canteen. Well, have fun with your nice mince, sweetie, because I shan’t be here for dinner tonight, thank heaven. I’m going out.’

Rowan sighed. ‘You could have told me,’ she observed with resignation.

‘I couldn’t tell you because I didn’t know myself until an hour ago,’ Antonia returned. ‘And I shall probably be late, so don’t bother to wait up for me,’ she added with evident satisfaction.

Rowan went into the tiny cramped kitchenette and began stowing the meat away in the ancient refrigerator, and piling the vegetables into the rack that stood beside the sink unit. She would make do with a poached egg later, she decided. She did the odd bits of washing up that had been left for her, then made herself a cup of instant coffee and carried it back into the living room. She set the cup down on the table and took her college file out of the bag, together with the reference books she had brought from the library that day.

‘More work?’ Antonia queried without interest. ‘You know what they say – all work and no play …’

‘Makes Jill a dull girl,’ Rowan concluded for her rather bleakly. She’d heard it all before. And she also knew that if she never lifted another finger as long as she lived, it would make her no less dull to Antonia.

‘You ought to get out more – enjoy yourself a little,’ Antonia declared. ‘You could look quite reasonable if you just took a little trouble with your appearance. As it is, no one would dream that you were nineteen.’

Rowan opened one of her books and studied the index with minute interest.

‘I’m not really concerned about appearing in other people’s dreams at any age,’ she remarked rather shortly. She was used to Antonia’s sniping by now, and didn’t let it disturb her particularly. Besides, she knew quite well that Antonia was quite satisfied that she appeared to be much younger than she actually was. It wouldn’t have suited her book at all to have a grown-up stepdaughter; she would have considered it ageing. When they had first moved to this particular flat, Rowan was quite aware that Antonia had informed some of the neighbours that she was her younger sister, and she had never bothered to correct this impression. If that was what Antonia wished people to think, then it was all right with her.

Antonia got up from the sofa and wandered across to look in the long mirror what was fixed to the wall.

‘I’m putting on weight,’ she complained, turning sideways to study herself. ‘It’s all this starchy food we eat. I shall have to go on a salad diet for a while.’

‘Do you realise what salads cost at this time of year?’ Rowan frowned as she tried to concentrate on her reading. It would be more sensible, she thought, to forget about trying to write an essay until Antonia had gone out, but on the other hand, Antonia was clearly in one of her difficult moods and Rowan wanted to avoid an overt row if possible. She shrank from scenes and raised voices, and always had done. Usually if she buried herself deeply enough in a book at times like this, Antonia contented herself with a few shrewish observations on her intellectual abilities and then relapsed into sulky silence.

‘That’s all you seem to think about – the cost of things!’

‘Well, someone has to,’ Rowan said temperately. ‘If we’re careful, we can manage, but …’

‘I’m sick of being careful – sick of managing!’ Antonia’s face was flushed with temper and her eyes were stormy. ‘Cooped up in this damned hole, day in, day out! At least you have that college of yours to go to.’

Rowan had to smile. ‘Well, you could always enrol for a course yourself if you wanted. And you do get out. You go anywhere you want, and you know it. You play bridge each week with Celia Maxwell and that gang and …’

‘I haven’t played with them for weeks.’ Antonia passed her hands over her hips, smoothing away the non-existent surplus.

‘I didn’t know that.’ Rowan gave her a surprised look. Bridge had always been one of Antonia’s passions.

Her stepmother’s lips tightened sullenly. ‘There’s a lot you don’t know. It’s all very well for Celia. When she loses at bridge, all she has to do is stretch her hand out to good old Tom and he’ll pay up without a murmur. She doesn’t realise it isn’t that simple for all of us.’

Rowan laid her pen down and regarded Antonia with startled eyes and parted lips.

‘Toni, do you owe Celia Maxwell money?’

‘Yes, I do as a matter of fact. Quite a hell of a lot, if you must know. I went on playing because I thought my luck was bound to change, only it didn’t. It just got worse.’ Antonia’s tone was bitter. ‘And if you don’t pay your debts in that circle, you’re soon persona non grata.’ Her voice sharpened. ‘And don’t look like that, for heaven’s sake. You must have known I played for money.’

‘I suppose so.’ Rowan pressed a hand to her head. ‘It just never occurred to me before. What are you going to do – ask Mr Tomlinson to advance you some of next quarter’s allowance?’

‘I asked him already,’ Antonia snapped, ‘and the answer was no. Instead I got a sermon on extravagance. My God, he’d never have dared when your father was alive!’

‘Maybe it would have been better for both of us if he had done,’ Rowan said soberly. ‘Will – will Mrs Maxwell insist on your paying?’

‘I don’t know what she’s planning. We’re not exactly on close terms at the moment.’ Antonia sounded petulant. ‘But I’ll find the money somehow. I’ll have to. Celia could make things damned uncomfortable for me if she wanted to.’

‘I wish you’d told me before,’ Rowan said unhappily.

Antonia’s brows rose. ‘Why? What good would it have done? What good has it done now?’ she asked. ‘Now I have you looking down your nose at me as well as old Tomlinson. Well, just don’t imagine I’ll stand a lecture from you. I’ll manage without any help from you.’

‘Is it this man?’ Rowan bit her lip as she met Antonia’s inimical stare. ‘The one you’re going out with tonight, I mean. Is he the one who advanced the money for the boutique?’

‘Yes, it is – if it’s any affair of yours.’ Antonia flounced back to the sofa and sat down, lighting another cigarette.

Rowan hesitated. ‘Do you think it’s wise – to put yourself so much in his power, I mean?’

‘My God!’ Antonia gave her a look full of derision. ‘You sound like the heroine of some Victorian novelette! Miss Puritan herself. This is the 1980s, sweetie, and the permissive society has been here for quite some time, although I can see it may have escaped your notice,’ she added with a curl of her lip. ‘You should give up writing essays and start on moral tracts. Everything in this world has to be paid for, my dear, even marriage with your estimable father.’

‘That’s a vulgar, hateful thing to say!’ Rowan said passionately.

Antonia was not offended, she appeared instead almost amused. ‘But the truth, sweetie, often is vulgar and hateful, as you’ll probably find out before you’re much older. I was younger than you when I realised what life was all about.’

‘I hope I never do, if that’s the case.’

‘That’s rather a forlorn hope.’ Antonia’s voice was bored. ‘You not only look like a child, Rowan, you are a child. But even you will have to grow up some time. And now I’d better do something about my nails. I wish to God I could afford a decent manicure.’ She got up, flicking ash casually on to the carpet, and wandered off towards her bedroom.

Rowan sat staring down at the table feeling utterly wretched. She supposed that ultimately it was none of her business what Antonia did. Her stepmother had her own life to lead, and her own values to lead it by, and she had not the least right to interfere. But at the same time, she felt that if she had kept silent she would in some strange way be letting her father down.

By the time she was ready to go out Antonia had recovered her good humour. She looked striking in swirling chiffon patterned in jade, peacock, lilac and gold, and she wore long gold ear-rings, and a collection of bracelets on one wrist.

‘Goodbye, sweetie.’ She tapped Rowan carelessly on the shoulder as she went towards the door. ‘Don’t read too much or you’ll get wrinkles and damage your eyesight. See you later.’

Rowan watched her go, and then on an impulse got up and went over to the window. The April sky was fading into twilight, but she could see quite clearly that there was a car parked just outside the front door of the flats. It was long and low and sleek, in some dark colour, but she could not catch a glimpse of the driver. No doubt he would be dark and sleek too, she thought with a grimace of distaste. She moved back as Antonia came into sight, and returned to the table and her studies. Pride forbade that her stepmother should glance up at the window and catch her peering out at them like a gossipy neighbour. But at the same time her ears were pricked for the sound of the car drawing away, even though common sense told her that those kind of engines rarely made any sound.

She found herself wondering where they would go. Out to dinner, of course, as Antonia had said – to some restaurant where the lights were low and the prices correspondingly high. And where did people go after that? Perhaps to some fashionable night-spot like Annabel’s, or even to one of the gaming clubs where Victor Winslow used to take his wife. Antonia had a passion for all games of chance.

Rowan stifled a sigh and pushed her books to one side. She could not concentrate tonight. She got up and walked across the room and stood studying herself in the mirror, much as Antonia had done, but without the same satisfaction. Antonia was right, she thought soberly; she did look like a child. In sudden dissatisfaction, she lifted the long straight fall of hair and piled it on top of her head experimentally. Other girls wore this style and managed to look graceful and careless; she looked merely untidy. She pulled a face at herself and let her hair fall back around her shoulders again.

She was too thin. Her top half was all collarbones and shoulder blades, and her breasts were too small. Her lower half looked good in the denim jeans she usually wore, because her hips were slim and she had long legs. Taken all in all, she thought, she looked totally colourless.

She remembered with painful vividness a remark she had overheard Antonia making to one of her cronies in the early days of her marriage. ‘Oh, the child is no bother. Darling, she’s so quiet, she’s practically non-existent.’

That’s me, Rowan told herself ironically, Miss Nonentity, and she made herself a small mocking bow.

She cooked herself the promised poached egg and ate it without appetite while she watched an old film on television. Then she switched off the single bar of the electric fire that she had been using, emptied the ashtrays, switched off the lights and went to bed with a glass of hot milk.

Their flat occupied the top floor of a large Edwardian house, and had been attics and servants’ rooms. As well as the living room, and the kitchenette which had been divided off from it, there was a large bedroom, occupied by Antonia, and a smaller room which had been divided into a minute bathroom and a boxroom. It was this latter that Rowan slept in. She had barely room to move round, but at least she had privacy. She would have hated having to share a room with Antonia.

She undressed and got into bed, then felt under the pillow, extracting a notebook and a ballpoint pen. This was her own time, and Antonia was not the only one to have a secret. Rowan wrote short stories. She had begun at school, encouraged by her English teacher, and she tried to write a little bit each evening before she went to sleep. She had always kept it from Antonia because she knew she would laugh at her. Of course, she was used to Antonia laughing at her really, but she didn’t think she could bear to have scorn poured on this. She had no idea whether what she wrote was any good. In fact, she rather doubted it. One day she would acquire a secondhand typewriter and send some of her work out to magazines, but not yet. If there was going to be a sad awakening for her, she did not want it to be quite so soon.

She was quite satisfied with her evening’s endeavours when she closed the book and slipped it under her pillow again. She switched off her bedside lamp and was soon dreamlessly asleep.

She did not know what woke her. She only knew that she was sitting up in the darkness, her heart thumping, listening intently. Then she realised what she was hearing. Someone was moving round in the living room. She sighed and her whole tense body relaxed in relief. It was only Antonia.

Yet Antonia did not have so heavy a tread, she thought with sudden unease. Nor did she normally bump into the furniture. Then she heard an unmistakably masculine expletive, and without considering the wisdom of her action, she pushed back the covers and jumped out of bed.

She flung open her door and took a step forward into the living room. She saw him at once. He was tall and lean, with tawny hair springing back from his forehead and curling slightly on to his neck. As Rowan entered, he turned to look at her and she saw that he was very tanned, as if he spent a lot of time abroad, and that in contrast his grey eyes were almost silver. He wore a dark green velvet dinner jacket and a frilled and ruffled shirt with a casual elegance that was in no way effete.

She had the craziest feeling that she knew him, that she’d seen him somewhere – perhaps in a newspaper or a magazine, but his name eluded her and the reason he had been photographed.

Then she looked beyond him and with a little cry of alarm she saw Antonia lying on the sofa, very white. The man had been bending over her, and there was a glass in his hand.

Rowan started forward. ‘What have you done to her?’

He stood very still and looked at her, a long hard stare encompassing her from the soles of her bare feet to the top of her head, and she blushed to the roots of her hair, realising what a spectacle she must make in her schoolgirlish gingham nightdress. It was a good job it was opaque, she thought, as she hadn’t bothered to throw her dressing gown on over it.

‘Who the devil are you?’ His voice was low and resonant with the faintest drawl.

‘I’m Rowan Winslow.’ Her voice faltered as she stared anxiously at Antonia.

‘Rowan?’ He frowned. ‘Oh, yes, the child. I’d forgotten …’

Antonia stirred slightly and muttered something and he turned back to her.

‘What’s happened to her?’ Rowan took a further step into the room, her hands tightly clasped in front of her. ‘Is she ill? Did she faint?’

His mouth twisted. For the first time she noticed a slight scar on his face near the corner of his mouth.

‘That’s a delicate way of describing her condition,’ he said sardonically. “‘Passed out” is the more usual phrase.’

‘What?’ Rowan’s eyes went disbelievingly from his face to Antonia’s unconscious form. ‘You can’t mean that – you’re saying that she’s …’

He nodded. ‘As a newt,’ he said pleasantly. ‘If you’ll indicate which is her room, I’ll put her to bed. And you’d better get back to your own before you catch your death of cold.’

Rowan was not listening. ‘You took Antonia out and got her drunk,’ she accused hotly. ‘That’s a swinish thing to do!’

He gave her another more searching look. ‘I took her out, yes.’ His voice was cool. ‘But I can assure you that her over-indulgence in alcohol was all her own idea.’

He bent and lifted Antonia into his arms. She was no lightweight, but he held her as easily as if she were a doll. There was something vaguely obscene about her helplessly dangling legs and the way her head lolled back against his arm, and Rowan swallowed uncomfortably.

‘Her room’s through there.’ She pointed. ‘If – if you’ll just put her down on the bed, I’ll do what’s necessary.’

His brows rose. ‘Aren’t you a little young to be coping with this sort of thing?’ he demanded. ‘Or is it quite a normal occurrence?’

She was just about to give an indignant negative to both his questions, when it occurred to her that perhaps it was no bad thing in the circumstances that he thought she was much younger than she actually was. If Antonia had been drinking to that extent, he could hardly be stone cold sober himself, and it was very late, and they were practically alone together.

‘It isn’t at all a normal occurrence,’ she assured him rather bleakly. ‘If you’ll wait a moment, I’ll fetch my dressing gown.’

It was a warm, unglamorous garment in royal blue wool which had seen service during her boarding school days, and she felt oddly secure once its voluminous folds had enwrapped her.

When she got to Antonia’s room her stepmother was already lying on the bed. The man was standing beside the bed, looking down at her, his face sombre and rather brooding.

‘Do you want me to help you with her dress?’ he enquired as Rowan came in. ‘Your wrists are like sparrows’ legs and you might have difficulty turning her over.’

‘I shall leave her as she is, thank you,’ she replied with dignity, resisting an urge to tuck the offending wrists out of sight in the sleeves of her dressing gown.

‘As you wish,’ he sounded totally indifferent. ‘But if she’s – er – ill in the night and ruins an expensive model gown, she’s unlikely to thank you.’

‘It’s really quite all right.’ She sounded like a prim old maid, Rowan thought despairingly. ‘You don’t need to stay. I’m quite capable of looking after her.’

He smiled suddenly, and she felt her mind reel under the sudden, devastating impact of his charm. Suddenly he was no longer an intruder – the stranger who happened to have brought Antonia home. He was very much a man to be reckoned with in his own right. Absurdly she found herself wondering how old he was. Possibly Antonia’s age, she thought, judging the hard, incisive lines of his face. Perhaps a year or so younger.

‘Do you know,’ he said slowly, ‘I almost believe you are. The question is – who looks after you?’

She was blushing again, and the disturbing thing was she didn’t really understand why.

She gave him a formal smile. ‘We really can manage now.’ She looked down rather uncertainly at Antonia. ‘I –I’m very sorry about all this,’ she ventured, then wondered vexedly why she should have said such a thing.

‘I’ll tell you one thing,’ he said softly. ‘Antonia will be a damned sight sorrier when she wakes up. She’s going to have a head like a ruptured belfry when she eventually opens her eyes, so I’d keep out of her way if I were you.’

He nodded to her and walked out of the bedroom. Rowan padded after him to the living room door, where he turned and subjected her to another of those lingering head to toe appraisals.

Then, ‘See you,’ he said lightly, and went out.

‘Not if I see you first,’ she thought as she secured the latch and shot the bolt at the top of the door. And then she realised with frank dismay that she didn’t actually mean that at all. In fact, she didn’t know quite what she did mean, and her mind seemed to be whirling in total confusion, although that could be because she had been startled out of her sleep.

She leaned against the door for a moment and took a long, steadying breath. It was then she remembered that she had never found out who he was.

She went slowly back to Antonia’s room and stood looking down at her. It was true, it was a lovely dress, and sleeping in it would do it no good at all. It was a struggle, but eventually she got Antonia out of the dress, and hung it up carefully in the wardrobe. Then she pulled the covers up over her stepmother’s half-clothed body, flushing a little as she remembered the stranger’s half-mocking offer of assistance. He was probably adept at getting women out of their dresses, whether they were conscious or unconscious, she told herself scornfully.

At least he’d had the decency to bring Antonia home, she argued with herself as she switched out the light. But then, returned a small cold voice inside her, what other course was open to him? Antonia’s condition had ruined the natural conclusion of the evening for them both.

Usually Rowan slept like a baby, but when she got back into her chilly bed, sleep was oddly elusive and she lay tossing and turning. In the end, she sat up in bed and said fiercely, ‘This is ridiculous!’ and gave her pillow an almighty thump as she did so.

She had met an attractive man; that was all that had happened. She had met others in the past, she thought, her mouth trembling into a rueful smile, and they hadn’t noticed her either. Nothing had changed, least of all herself. He was very adult, and very male with that tanned skin and those pale mocking eyes, and he had looked her over and seen what there was to see, and he had called her a child.

‘Perhaps that’s what I am.’ She squinted sightlessly through the darkness towards the window where a paler light was beginning to be perceptible through the thin curtains. ‘A case of arrested development, small breasts, chewed nails and all.’ The thought made her smile, but it did not lift her heart, and when she fell asleep she dreamed the small unpleasant dreams that cannot be recalled to mind the next day, yet hang about like an incipient headache.

The next day was Saturday, so there were no lectures, but she had to go to the library to exchange an armful of books, and there was the weekend shopping to be done. She breakfasted quickly on toast and coffee and looked round Antonia’s door to see if she wanted anything before she departed, but Antonia was still sleeping like the dead.

Rowen bought vegetables and fruit from a street stall at the corner on her way home from the library and agreed with the vendor that winter really did seem to be over at last, wriggling her shoulders in the pale warmth of the sunlight.

She felt almost cheerful as she walked in at the front door and came face to face with Fawcett, their landlord. He was making his weekly rent round, and she said smilingly, ‘Good morning. Did Mrs Winslow hear you knock? If not, I can …’

‘I have the rent,’ he said rather dourly. ‘I’m very sorry to hear that you’re leaving us. You’ve been good quiet tenants. I could hardly have wished for better.’

Rowan stared at him. She said at last, ‘I don’t quite follow—are you giving us notice?’

He looked quite shocked. ‘On the contrary, Miss Winslow. Your stepmother told me herself that you would be leaving at the end of the month.’

‘Oh, no, there must be some mistake.’ Rowan drew a long breath. She said urgently. ‘Please, Mr Fawcett, don’t advertise the flat yet. My—my stepmother hasn’t been well lately and …’

‘She certainly didn’t look very well.’ His lined face was suddenly austere with disapproval. ‘But I hardly feel there’s any mistake. Mrs Winslow handed me her notice in writing. Perhaps it’s a matter you should discuss with her rather than myself.’

Rowan was breathless by the time she reached their front door. She pushed the key into the latch and twisted it, and the door gave instantly. Antonia was on her knees at the sideboard and she looked round as Rowan marched in.

‘I’m looking for old Fawcett’s inventory,’ she said without preamble. ‘It must be around somewhere, and I’m damned if I’m leaving anything of ours for the next tenants.’

‘So it’s true.’ Rowan dropped limply into one of the chairs beside the dining table. ‘What have you done? I know it’s not Knightsbridge, but it’s clean and quiet and cheap and he doesn’t bother us.’

Antonia got up from her knees. ‘You don’t have to sing its praises to me,’ she said shortly. ‘I’m quite aware of all its dubious advantages, including the low rent. Unfortunately even that is more than we can afford just at present.’

‘Since when?’ Rowan began to feel as if the world was tottering in pieces all around her.

‘Since last night.’ Antonia came over and sat down on the opposite side of the table, facing her. She was very pale, and her eyes were narrowed as if the light was hurting them. She looked across at Rowan’s suddenly bleak face and gave a small rather malicious smile. ‘But don’t worry, sweetie, we won’t be sleeping on the Embankment just yet. We do have another hole to go to.’

‘One that we can afford?’ Rowan moved her stiff lips.

‘Rent-free, my dear, in return for services rendered. Only not, I fear, in London.’

‘Not in London?’ Rowan repeated helplessly. ‘But Antonia, I can’t leave London—you know I can’t!’

‘I had no idea you were so devoted to the place,’ Antonia retorted. ‘I always had the feeling you preferred that place in Surrey.’

‘Well, so I did,’ Rowan stared at her with sudden hope. ‘Is that where we’re going—Surrey? Oh, that won’t be too bad. I can easily …’

Antonia shook her head. ‘So sorry to disappoint you, but our destination is several hundred miles from Surrey,’ she said rather harshly. ‘We’re going to the Lake District, to a place called Ravensmere. I don’t suppose you’ve heard of it and I understand it’s too small to have appeared on any but the most detailed of maps,’ she added with a faint curl of her lips.

Rowan listened to her in stunned silence, then moistening her lips, she said, ‘I—I don’t believe it! You even hated the place in Surrey. You said it was too remote, and now you’re actually considering going to the other end of England.’

‘I’m not considering anything,’ Antonia said flatly. ‘I’m going, and you’re going with me.’

Rowan shook her head. ‘No way,’ she said steadily. ‘I have a course to finish and exams to take, in case you’d forgotten.’

‘I’ve forgotten nothing.’ Antonia drew her pack of cigarettes towards her and lit one irritably. ‘Perhaps you’ve forgotten that all-important clause about our sharing the same roof until you’re twenty-one.’

‘Indeed I haven’t. We’ll just have to tell Daddy’s solicitors that we found it—impossible to comply with.’

‘We’ll do no such thing,’ Antonia returned inimically. ‘That money is a lifeline as far as I’m concerned, and you won’t find it so easy to make out as you seem to think once it’s gone.’

‘I’ll manage.’ Rowan lifted her chin stubbornly. ‘And if it means that much to you, you could manage too. We can catch Mr Fawcett and tell him you’ve changed your mind about leaving and …’

Antonia’s hand shot across the table and gripped Rowan’s arm. She had been on the point of rising, but she hesitated now, almost pinned to her seat.

‘Unfortunately, it’s not as easy as that.’ Antonia paused. ‘You remember all the trouble that Alix and I had over the boutique’s closure?’

‘Not particularly,’ Rowan said drily. ‘It seemed to me at the time that the pair of you had emerged virtually unscathed.’

‘But not quite,’ said Antonia with a little snap. ‘I’d arranged all the financing, as you know, and I believed that my—backer was prepared to write the whole thing off as a loss.’ She paused again. ‘But I was wrong. He’s demanding payment in full.’

Rowan gasped. ‘But when did you discover this?’

‘Last night.’ Antonia stubbed out her half-smoked cigarette in the saucer of a used coffee cup. ‘By the way, just as a matter of interest, who put me to bed?’

‘I did, of course.’

‘There’s no “of course” about it.’ Antonia sounded almost amused. ‘It wouldn’t have been the first time Carne had seen me without my dress, you know. I presume he did bring me back, and didn’t just abandon me to the mercies of some taxi driver?’

‘There was a man here.’ Rowan felt a betraying blush rise in her face and mentally kicked herself.

‘Was there?’ Antonia nodded gently, her eyes absorbing Rowan’s overt embarrassment. ‘I’ve known him for years, of course. His mother and mine were some sort of distant cousins—hundreds of times removed, of course, and too boringly complicated to explain or even remember. But Carne and I did see a lot of each other at one time. We even nearly got engaged. He was hopelessly in love with me,’ she added.

In spite of herself, Rowan found she was visualising that dark, proud face with its cool, sensual mouth, and trying to imagine its owner in a state of hopeless love with anyone. It was not easy.

Without thinking what she was saying, she asked, ‘How did he get that scar?’

‘My word, we were observant,’ Antonia mocked. ‘I’ve no idea, actually. I expect one of his women bit him. But don’t get any ideas, sweetie. He eats little girls like you for breakfast.’

‘How desperately unconventional,’ said Rowan, trying for lightness. ‘Has he got something against cornflakes?’

Antonia was not amused. ‘You know what I mean,’ she said petulantly. ‘He is out—but out of your league, ducky, and don’t you forget it.

‘I’m not likely to.’ Rowan felt suddenly listless. ‘Anyway, it’s unlikely that we’ll ever meet again, so let’s drop the subject.’

Antonia sighed abruptly and her shoulders seemed to sag. ‘Would that we could,’ she said. ‘But that’s what I’ve been trying to tell you. It’s dear Cousin Carne to whom I owe all this money, and as I can’t repay him in cash he’s insisting that it has to be in kind. He has this house at Ravensmere which an old aunt looks after for him. But she’s got arthritis now, or some crippling thing, so the idea is that I go there for a while and act as his housekeeper in her place.’

There was a long silence as Rowan stared at her in utter disbelief. Then, ‘Oh, God give me strength,’ she said, half under her breath. ‘Is he serious?’

‘Of course he’s serious. That’s the deal. I go up to this mountain hellhole of his for as long as it takes while I—purge my contempt, I suppose.’ Antonia’s lips thinned. ‘He’s also offered to pay off any other debts I may have, including Celia’s, so I can’t accuse him of being ungenerous.’

‘It’s not a question of that.’ Rowan shook her head. ‘You don’t even know how to keep house. Does he know that?’

Antonia shrugged. ‘The subject wasn’t raised. He knows I ran the Surrey house and the other flat without any problems. Naturally, he wasn’t a frequent visitor because your father, to speak plainly, sweetie, was jealous of him.’ She gave a little knowing smile that made Rowan feel sick. ‘Not altogether without cause, I may say.’

Rowan pushed back her chair and got to her feet. ‘That being the case,’ she said quietly, ‘the last thing you’ll want is my presence in the house. I’m sorry you’re in this mess, Antonia, but it’s of your own making, and there’s nothing I can do about it. From now on we go our separate ways.’

‘Oh, but we don’t.’ Antonia’s eyes glittered as she stared up at her stepdaughter. ‘I have no intention of serving my term and then finding myself without a penny. I do have—plans, naturally, but I also intend to keep all my other options open, and I’m not seeing your father’s allowance just whistled down the wind. Besides, the deal includes you. I told Carne about Victor’s will, and he was most understanding.’

‘How good of him!’ Rowan’s eyes flashed. ‘But I would prefer not to be carted round Britain like so much excess baggage. I can manage to support myself for the next two years. There are grants and …’

‘And what about me?’ To her horror, Rowan saw enormous tears welling up in Antonia’s eyes. ‘Your father wanted us to stay together, you know he did. You’re all of his that I’ve got left. You can’t leave me, Rowan!’

Rowan was aghast. ‘That’s cheap blackmail, and you know it,’ she began roundly, but Antonia was crying now in real earnest.

‘Rowan, you’ve got to come with me. It will only be for six months or so at the most. You can go on with your course afterwards—do what you like. If you don’t come with me, then the whole arrangement is cancelled and Carne is going to make me bankrupt. He threatened to last night. Why do you think I drank so much?’

‘But he hardly knows of my existence …’

‘Of course he does. And there’s another thing.’ Antonia bent her head over her wedding ring, twisting it aimlessly on her finger. ‘I—I let him think you were younger than you actually are. You don’t look your age, Rowan, you know you don’t. It wouldn’t be any hardship to pretend—just for a little while.’

‘How old?’ Rowan said baldly.

Antonia concentrated on her wedding ring. ‘Sixteen,’ she returned after a pause.

‘Sixteen?’ Rowan sank back on to her chair, her legs threatening to give way beneath her. ‘Antonia, you are unbelievable! You can’t do this to me.’

‘And you can’t do it to me,’ Antonia retorted sullenly. ‘They take everything from you when you’re bankrupt. There was talk of an investigation after your father died, but it was smoothed over. If Carne bankrupts me, the whole thing could start again. Do you want to see the Winslow name dragged through the financial mud?’

‘No,’ Rowan acknowledged. ‘But I don’t think it will come to that.’

‘Oh, yes, it will,’ Antonia said softly. ‘For one thing, Carne has never forgiven me for marrying Victor. When he offered to back me in the boutique, I thought it was an olive branch, but I realise now that he just wanted to have a hold over me. It was as if he knew the boutique was going to fail.’

‘Well, he wouldn’t have needed much business acumen to tell him that,’ Rowan said drily. ‘What is he? Something in the City? I thought I knew his face from somewhere.’

Antonia grimaced. ‘Well, it’s more likely to have been the gossip columns than the financial pages. You’ve heard of him, of course—I’m surprised his name didn’t ring a bell. He’s Carne Maitland.’

‘The painter?’ Rowan could hardly believe her ears. The most surprising element in the story was that Antonia should be even distantly related to one of the most famous portrait paiters in Britain and have failed to mention it.

‘The very same.’ Antonia smiled lazily, her tears forgotten. ‘Did you notice his tan? He’s been out in one of the oil states, painting a sheik. They’re about the only people in the world who can afford his prices these days. Of course, he doesn’t need the money. His parents each left him a fortune, and he still has the controlling voice in the family business. Painting was always his hobby when he was a child, but everyone was amazed when he went to art college and began to work at it seriously. Who says you need to starve in a garret to be a success?’

Certainly, Rowan thought, not the critics, whose laudatory remarks had greeted every new canvas in recent years. He had had some dazzling commissions of late, including the obligatory Royal portrait, and had fulfilled them brilliantly. And he was Antonia’s distant cousin, and a former lover, to judge by her words.

She got up and went over to the window, gazing down into the busy street outside with eyes that saw nothing.

‘So I can tell him it’s all right?’ From behind her, Antonia’s voice sounded anxious. ‘I can tell him to expect us both?’

Rowan moved her shoulders in a slight shrug. ‘Tell him what you like. That’s what you’ve done up to now, isn’t it? I’ll come with you, but for Daddy’s sake, Antonia, not yours.’

And not mine either, she thought, as she began the weary task of locating the missing inventory. Because the last thing she needed was to find herself in Carne Maitland’s orbit again. She could still feel the lingering scrutiny of those silver eyes, and the memory disturbed her more than she cared to acknowledge, even to herself.

Not that she had anything to worry about, she told herself ruefully, as she caught a glimpse of her reflection in the long mirror. The beautiful, the rich and the elegant—those were the type of women with whom his name was most often linked, and she didn’t qualify under any of those headings. Quite apart from the fact that he regarded her as a child, she had no doubt at all that he found her looks and personality about as fascinating as a—stewed prune.

And that was meant to be a joke, so why was she finding it so hard to smile? Rowan sighed, thankful that the tenor of her thoughts was known only to herself.

This could prove to be the most difficult summer of her life. And she thought, ‘I’m going to have to be careful. Very careful.’