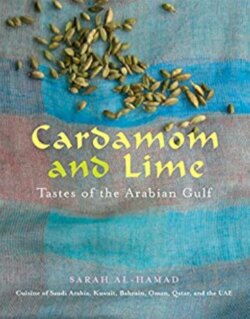

Читать книгу Cardamom and Lime - Sarah Al-Hamad - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe ARABIAN GULF: Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, a cluster of countries dotting the Arabian Sea coast, collectively they are al-Khaleej. This is a book about the food of the Arabian Gulf.

For hundreds of years the deserts and ports of the Arabian peninsula were inhabited by disparate tribes. Originally the bedouin roaming the deserts relied heavily on a diet of dates and dairy products, rarely meat. Life was difficult and there was little by way of natural resources.

In the pre-oil days, the Gulf’s main sources of livelihood were pearling and trade. Later the merchants’ travels brought a wide array of imported food items and methods of cooking. Arabia has long been a centre of trade. Its position on the trade route from Africa to India was fortuitous, and it was on the dhows (traditional Arab sailing vessels) from India that the first spices and ingredients entered the region. Fragrant cardamom pods, cloves, saffron threads, cumin seeds, chilli and curry powder – and long-grain basmati rice. The food of the Gulf is largely a combination of Indian, Persian and Turkish cuisine.

Cultures living by the sea (al-bahar) inevitably develop a closeness to it. Wherever you go in the Gulf – most khaleeji cities are built up along their coastlines – the sea is ever-present and a source of beauty. One of my favourite films is the Kuwaiti Bas ya bahar (1971), a sensitive yet cheerless rendering of life in the days when pearling was the common man’s fate; the film beautifully illustrates this give and take with the sea and its dominance in everyday affairs. Pearling is obsolete today but the sea remains a strong symbol of the past. It is still vital to the economies of the area; sea-sports and fishing are also popular.

Alleyway in Muharraq, Bahrain

The Gulf went from relative poverty to astonishing prosperity in the span of a half a century. It now has one of the highest birth rates in the world. Seen as a land of opportunity, the region started attracting South Asians in the 1960s. This phenomenon affected people’s dietary habits. While researching this book, most of the cooks I met were from India or Bangladesh. These migrant workers may live and work for decades in the Gulf, integrating into the families they join. A cook’s training involves learning traditional recipes as well as continental dishes like pasta, fancy salads and desserts. A source of pride and envy, cooks are regularly ‘loaned out’ to friends to teach other cooks a special dish or train newcomers. It is common for households to have a cook, even if the homemaker is a good one herself; families are large and food sharing is central to local life.

Old dhows and fishermen in Fahaheel, Kuwait

To understand food-sharing is to get at the core of the role food plays in mediating social relations in the Gulf. In the olden days, communities were small. Neighbourhoods consisted of houses clustered together and socialising took place mostly among men in an open courtyard, where they gathered and strangers were easily identified. A woman’s place was firmly in the home, her social affairs confined to relatives and neighbours. Homemaking and childrearing would have been her primary roles. The housewife would cook every day, but always making a little extra to share with neighbours or surprise guests.

In much the same way nowadays, lunch or dinner is offered at happy occasions but also at times of bereavement; relatives and neighbours still engage in food exchanges that can last for years and dishes periodically travelling between homes. Wealthier households with large social networks have a quasidedicated catering system complete with hotel-style stainlesssteel boxes and transport van.

Food also tops the list of gifts to bring back from trips abroad. I remember crates of Alfonso mangos appearing every year at the same time, beautifully ripe and sweet, sent from India by one of my father’s friends, or sacks of pistachios brought back from Iran, honey from Yemen, wonderful sesame-covered biscuits from Syria and Lebanon and dates sent over from Saudi Arabia – each country renowned for a special food.

A venue where food makes a strong appearance is the diwan or diwaniyya (also known as the majlis in some countries), that most important of informal social institutions. The diwaniyya is typically a male social space where friends and relatives gather, usually in the evenings, to catch up, talk business or politics, or to gossip. It can be a simple room attached to a person’s house, or a lavish hall where weddings and other rites are held. Diwaniyyas are family-specific. In Kuwait, the institution is especially strong and most local families will have one – it is a mark of status and prestige. Tea, coffee and fresh juices are a fixture at these gatherings, finger snacks like sambousa (samosas) and batata chab (potato ‘chops’) are sometimes offered and dinner is served when the gathering thins out to family members.

No dish typifies Gulf cuisine better than the machbous. Inspired by the magnificent Persian and Indian biryanis, the machbous derives its name from the Arabic for compressed, kabs. It is a cooking method which re-uses the spiced water used to cook meat or fish to suffuse the rice, marrying the ingredients and spices together. The resulting dish is a celebration of robust perfumes and ingredients, scented with cardamom, cloves and cinnamon. There are many types of machbous (pl. michabees) – lamb, chicken, prawn and fish machbous are weekly menu fixtures, while truffle machbous and duck machbous are seasonal delicacies. Once learned machbous-making can be adapted to include a variety of ingredients.

The Arabic for rice is riz/ruz, but in the Gulf it is ‘aish – or Living – evidence of its elevated status. Here lunch is the main meal of the day. Because of the heat, the working day starts early, usually around 7am, and ends at about 2pm. People lunch late and heartily and dinner is a meagre affair by comparison. In our home and wherever I have lunched over the years, it is inconceivable for lunch to be served without rice. The same applies to practically every household in the Gulf; rice is bought by the sackful.

Rice may be the unrivalled staple food today but it wasn’t always so. Before trade introduced it to the peoples of the coast and at times of scarcity, locally farmed grains like barley, jareesh (coarse wheat) and lentils were used. These would be cooked with whatever vegetables were in season (rarer still with meat) for several hours, then beaten to a savoury porridge that was nutritious and filling. Wholesome grain-based dishes are still very popular, especially at Ramadhan and in winter.

Combining sweet and savoury is also characteristic of Gulf cuisine. Raisins and crispy onions are sprinkled over rice and savoury porridges, fish is served with date-sweetened rice, eggs accompany some puddings and desserts. Eating dates throughout the meal, in between morsels of machbous or rice is common; bowls of dates always accompany the main meal.

The most important regional food – and my great weakness – is the date fruit, tamr. Its value as a cultural player transcends its significant culinary worth. As a child I would hear my father say that a man could live on dates and yoghurt alone, so complete and nutritious is the combination. Date palms are highly prized, their ownership a source of pride and prestige; I have never seen an unkempt, neglected palm tree – the mere idea seems subversive, even unreligious (date palms are the most frequently mentioned fruit-bearing tree in the Quran). Each year the palms are pollinated and pruned. Only female trees bear fruit (the male ones pollinate), their fruits patiently awaited. The yield is stored for eating and cooking and any extra divided up among family and friends. The best-known kinds are the khlass and the birhi, but there are myriad varieties, each with a distinctive shape, sweetness, texture and colour. Most of the dessert dishes in this book are made with dates, their high-energy, nourishing flesh perfectly suited to the region’s arid, austere climate.

In addition to its valuable fruit, the palm’s juice (dibs) is used for baking and cooking and its branches for weaving baskets and mats.

Another important local produce is the dried lime, lumi, widely used to add sourness to stews and soups. Also popular in Persian cooking but originally from Oman, along with dates they are the two locally cultivated ingredients.

Probably because alcohol is forbidden and mostly avoided in the Gulf, food is Big. It occupies a central position in local life and culture. It is a means of communication and a social marker, a peace-offering, a way of demonstrating largesse and hospitality to friends and family, a form of one-upmanship, an everyday conversation starter, a boredom buster and an arena for female competitiveness. Recipes are coveted and secretly exchanged; specialities are shown off at gatherings – cooking and eating are a big part of everyday life.

What astounds is the sheer expanse of the food industry, in evidence everywhere – the heaving, crumbling old souks rubbing shoulders with gleaming megamarkets, price-controlled local cooperatives and neighbourhood corner shops; fastfood giants like McDonald’s and Pizza Hut wooing customers with scintillating highway billboards; smaller, Middle-Eastern shawarma and kushari kiosks and the speciality restaurants catering to migrant workers from the Philippines, India and Egypt; the sweet factories, flour mills, fruit and vegetable wholesalers, livestock importers, date merchants, fish markets, spice shops, and the plethora of stylish, high-end, world-food restaurants.

When I embarked on this project I had no idea what treasures awaited me. Not only how much fun I would have recording these recipes, photographing streetfood and souks and cooks at work, and savouring the results, but the people I would meet: fishermen fresh off the dhows, effervescent housewives, Indian and Bangladeshi cooks and pastry chefs fluent in Khaleeji Arabic, tea-sipping grocers, butchers, caterers, shawarma carvers, date and spice merchants, bakers, and legions of eaters.

A colourful kiosk in Muharraq, Bahrain

Giant pots used for cooking rice and stews in the Gulf

The bulk of recipes in this book I collected from family and friends and friends of family and friends of friends. One cook led me to another and wherever I went there was great generosity in discussions about food and sharing of culinary titbits and recipes. I did not encounter ambivalent foodies; over-whelmingly, I found food associated with good things – pleasure, companionship and tradition. In conceiving this book, my intention had been to introduce the Arabian Gulf through its cuisine and the diverse culinary traditions that have shaped it; I also wanted to preserve, in words and images, the ‘traditional’ markets and foods of the Gulf vis-à-vis an encroaching fastfood culture.

The recipes in this book were recorded while each dish was being cooked. My camera transformed kitchens into studios and cooks into chefs and at the end of every day we all gathered around my laptop screen. Months later and thousands of miles away, the images would jog my memory when gaps appeared in the notes. Once the recipes were on paper I tested them on eager friends. That was fun, and enabled me to understand the characteristic nature of Gulf cuisine, how varied and individual it is, and that the proof is in the spicing – how much is used and which spices with which foods is where the difference lies. There are as many ways of spicing a dal soup as there are dal recipes (and there are a few!). Invariably, the distinction lies with the cooks, their culinary background and each household’s preferences. The recipes were somewhat modified to suit my taste; you should adapt them to yours. The quantities of spices used are guidelines only. Gulf cuisine is rarely available at restaurants (I know of only two restaurants in the world) because every household has a set of signature dishes and its own way of making flavoursome food. I have tried to collect the recipes most common to all six Gulf countries, and by and large these are. But no region is monolithic and cultural differences are what add spice to life, the stuff of enriching and complex experiences – culinary and other.

Shomali Sweets Factory in Shuweikh, Kuwait City