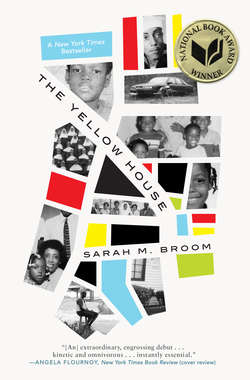

Читать книгу The Yellow House - Sarah M. Broom - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

IV Simon Broom

ОглавлениеFour years later, in the spring of 1964, Sarah McCutcheon died.

That summer, Mother married Father in the backyard of 4803 Wilson Avenue in New Orleans East.

Carl, Ivory Mae’s first child with Simon, was not yet a year old. During the wedding he sat perched on Mom’s right hip, his foot kicking against her pregnant belly, knowing nothing of the scene taking place right in front of his eyes. Karen, Mom’s fifth child, would be born that fall and come home to this rented three-bedroom brick house.

Reverend Ross, who worked with Simon Broom at NASA, officiated. The nice neighbor living in the other half of the double house, who was also the landlord, had made for the reception white-bread finger sandwiches with the brown edges cut off the way Mom liked them.

Auntie Elaine, my mother’s sister, who was grown up now and had started wearing her signature flaming red hair, stood there as witness. It wasn’t a big deal. It wasn’t no event. That seems a long time ago now, and Mom closes down passageways to memory when something doesn’t make sense or when the thing or person no longer exists, which is possibly the same thing.

It was never just the two of them, Ivory and Simon, not even at the beginning of their story. They each came to the relationship with children and with spouses. According to Mom, she first saw Dad in the late fifties at his cousin’s hole-in-the-wall bar somewhere in the vicinity of Roman Street, where he had come to play a card game. Auntie says they first met at her marriage to Webb’s cousin Roosevelt. One of Dad’s brothers said they met at a restaurant where he and Simon were working as busboys. Wherever it was, they first laid eyes on each other while Ivory was still married to Webb, before she had any idea how that would end. Simon had a wife, too, but they were separated, he told Ivory in so many words. He was, in still other words, skirting the truth. Anyway, this was not about practicalities yet but about what flourished between them, those delirious feelings.

Simon Broom was six feet, two inches and dark skinned with keen features, the handsomest man I ever seen. Opposite Webb in looks and style, he physically overwhelmed her. Projecting an ease that Ivory Mae loved, he seemed a man in possession of himself, if not things. Nineteen years her elder, he had massive hands, gray-stained from years of work, which meant, Ivory Mae reasoned, that he could fix whatever in his and her world was broken. Plus, his diction. He had a proud talk. Like the Kennedy brothers. When he spoke, I felt like I just needed to be listening. His booming voice seduced Ivory, scared some, and led others to want to fight.

One thing was certain: Simon had not simply happened to her, as had Webb. Simon Broom felt like a choice. She took him on.

He was born to Beaulah Richard and Willie Broom in Raceland, Louisiana. Beaulah was a Creole-speaking, pipe-smoking woman. They built their own farm in Raceland on a nameless edge of town near a street now called Broom. Simon was the third youngest of eleven children, only three of whom were girls. By the time thirty-eight-year-old Simon met Ivory Mae when she was nineteen, he had already lived several lives. He had spent his childhood working on the family farm. School, held in the local black church, consisted of several classes taught simultaneously in one large room with no walls. Most days were chaos, but Simon finished fourth grade.

When he was sixteen, cousins brought him to New Orleans, an hour—a whole universe—away from Raceland. People say family friends taught him how to act citified then, and that is how he came to speak proper, learn to dress sharp, and have the high-class bearing that my mother fell for. But this sounds like a story city people tell other city people about country people. In 1943, at nineteen years old, Simon claimed he was two years older in order to join the navy, as had most of his brothers before him. When he enlisted, Ivory Mae was still toddling around Sarah McCutcheon’s house in the Irish Channel, making dolls out of Coke bottles. He served in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater, in what in America is called the Philippine Liberation and elsewhere the Battle of Manila, the brutal fight that helped end World War II. He earned five stars fighting on behalf of a country that listed his name on a roll-call docket as: Simon Broom (n), the (n) for negro or negroid or nigger.

After the war, Simon Broom was handed a check for $167.36 and set free to make a life for himself. Asked, on discharge papers, about his ideal job, he wrote: “Assistant Manager (half owner) of moving van.” Years after his military release, when Ivory Mae was seven years old, Simon married Carrie Howard, whose large family had come from Hahnville and New Sarpy, tiny towns thirty miles from New Orleans. In 1949, when Carrie and Simon’s first child, Simon Broom Jr., was born in Charity Hospital, Simon the father was already working as a longshoreman. Carrie worked, too, first as a secretary at the naval base and then as a clerk at the Orleans Parish School Board. She was not the type to suffer fools. She was an organist in church, believed deeply in education, and bore for Simon two more children, named Deborah and Valeria, to whom she preached her convictions.

When Simon and Ivory Mae met all those years later, his age and experience were precisely what drew her. When Simon danced close to Ivory and she looked up at him, her hips rowing the air, he told her about how he had never—as a middle-aged man—had a woman so much younger, not in his lifetime, almost but not yet. He knew how to put the right words together.

But Simon wasn’t no dating type of man. He wasn’t no going to the movies kind of man, either. He mostly worked. His mantra was “I’ll sleep when I’m dead.” Like his father, Willie, he played the trombone or sometimes the banjo or the tuba in Doc Paulin’s Brass Band, and he would often take Ivory Mae along with him, the two of them alone together, for once without the children, riding to gigs in his near-to-broken-down car, the instruments between them.

Simon’s eldest boy would never live with his father and stepmother the way his sisters would. After his mother, Carrie, died in the summer of 1963—two weeks before Carl was born—Simon Jr. stayed in the same high school, living with his grandmother Beaulah Richard in rural Raceland, surrounded by the cousins and classmates he knew. He’d won a scholarship to Johnson C. Smith College. Simon Broom Sr. put him on a Greyhound bus to Charlotte, North Carolina. He has been there ever since.

Simon and Carrie Howard Broom’s daughters, Deborah and Valeria, ten and eight years old, were still reeling from their mother’s sudden death when they moved into the rented brick house on Wilson after the wedding. Valeria seemed numb, but Deborah, who was older, fought out her rejection of this new arrangement. She was direct and loudmouthed, striving to upend, it could seem, this imposed, unnatural order of things. She asked questions. She spoke her wants and wishes.

She had already seen what silence brought. The entire summer when they were away in Raceland at Grandmother Beaulah’s house, surrounded by kin, their mother was back in the city, battling leukemia, dying. “I didn’t know what the heck was going on because nobody was telling us details,” Deborah says.

Deborah first learned about her new family while living with Grandmother Beaulah in Raceland shortly after her mother died. A neighbor was combing Deborah’s hair; she was on her way to be baptized. “She started rolling out this scenario. These are gonna be your brothers,” the woman said to her, describing Eddie, Michael, Darryl, and Carl.

“No they not,” Deborah returned. “I don’t even know these people.” She considered it awhile longer, then asked again: “Who are these people?” “But it wasn’t up to me,” she says now.

Eventually, the girls were taken to meet the strangers. Deborah screamed and hollered, “ ‘Where is my mom?’ I kept saying I don’t want to go meet these people. That first year after my mom died, I went crazy. I was in a shell-shocked state almost.”

On a winter morning, Simon Broom drove Deborah and Valeria from Raceland to meet Ivory Mae and her four children for the first time. Simon left them there until sometime before night. He was the kind of man who always had another place where he urgently needed to be.

When the sisters arrived, they saw Eddie, Michael, and Darryl, “three beady-eyed boys,” says Valeria, staring back at them. And Ivory Mae, their father’s new woman, thin everywhere except for in the stomach (she was pregnant with Karen) and light skinned. The new woman, as Deborah and Valeria saw her, walked quietly around with little expression; they remember her as mostly silent with exploring, sometimes critical eyes. She looked and behaved nothing like their mother, Carrie, who was tall with a booming talking voice and a deep tenor singing one. “I’m Miss Ivory,” Mom said to Deborah and Valeria. They would call her Miss Ivory for the rest of their lives.

The girls later moved into that rented brick house on Wilson. Four-year-old Eddie, firstborn of Ivory Mae’s biological children, was suddenly younger than his new sisters. Deborah, who had been a middle child, was now the second eldest and Valeria the third, ranking above Eddie, who, before the girls arrived, had been the serious older brother to Michael and Darryl. Eddie was practical and special feeling, surrounded by doting aunts—Webb’s sisters—and Mrs. Mildred who needed him to stay alive the way his dead father had not. Eddie would fight to keep hold of his original position as eldest of Mom’s children for the rest of his life, seeing the new rearrangement as an unlawful jerking away of his familial standing.