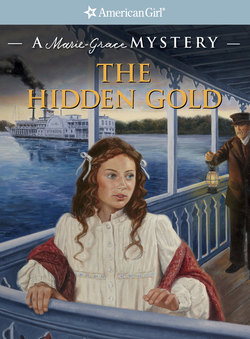

Читать книгу The Hidden Gold - Sarah Masters Buckey - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

An Unexpected Traveler

In her tiny stateroom aboard the steamboat Liberty, Marie-Grace Gardner carefully set her inkwell on the table beside her bed. Then she dipped her pen in the ink and wrote,

Monday, March 13, 1854

Dear Cécile

My papa and I came aboard this morning. The crew is still loading cargo on the boat, but Papa says we’ll be leaving New Orleans soon. The Liberty is the biggest steamboat I’ve ever seen. The main cabin is as fancy as the ballrooms at the Grand Théâtre.

As she dipped her pen again, Marie-Grace smiled to herself. She was sure that Cécile would remember the elegant building where they’d had their first adventure together.

There’s a little girl named Annabelle Rumsford on board. Her mama asked if I’d play with her this morning. While Annabelle and I were on deck, I saw an artist painting pictures of the river. It reminded me of your brother Armand. I hope

Marie-Grace stopped in mid-sentence as the door to her stateroom swung open.

“I found you, Marie-Grace!” a little girl with blonde curls declared triumphantly. Holding her rag doll, Priscilla, close by her side, Annabelle rushed into the room and plopped herself down on the bed, right next to Marie-Grace.

Oh dear, thought Marie-Grace. Annabelle was a cheerful little girl, full of energy and eager to play. Marie-Grace was happy to spend time with her, but right now she wanted to finish her letter.

“Hello, Annabelle,” Marie-Grace greeted her. “Are you finished with your nap already?”

“I wasn’t tired at all, so Mama said I could get up.” She leaned over the letter that Marie-Grace was writing, and her elbow smudged the fresh ink. “What are you doing?”

“Writing a letter,” Marie-Grace said, moving the paper out of Annabelle’s reach.

“I want to write a letter, too!” said Annabelle, swinging her legs from the edge of the bed. “May I use your pen? Please?”

Marie-Grace hesitated. Her stateroom wasn’t much bigger than a large closet, but it was freshly painted and very pretty. There were two narrow beds set into the wall, one on top of the other. Both berths had white embroidered covers, and there was a delicate white cloth on the bedside table. Marie-Grace had already noticed that Annabelle was apt to get into mischief. So far this morning, the little girl had accidentally knocked over a bucket of water on the deck, and then, when she was running to tell her mother, she had slipped and fallen in the puddle she had made.

If Annabelle spills ink in here, I’ll never be able to clean it up, thought Marie-Grace. “I’ll finish my letter later,” she told Annabelle. Marie-Grace put the cork back into the ink bottle and tucked it inside her trunk, along with the letter.

For a moment, Annabelle’s blue eyes clouded with disappointment. Then she brightened. “Let’s go out on the deck again and throw bread.”

Marie-Grace and Annabelle had fed the gulls earlier, and Marie-Grace still had one thick crust of bread left. “All right,” she agreed as the steamboat’s bell clanged. “We’ll be sailing soon, and then there won’t be as many birds.”

Annabelle grinned and hurried to the open door. “Mama!” she called. “Marie-Grace said she’ll take me to feed the birds again.”

“I’ll be there in a moment, too, dear,” Mrs. Rumsford answered from the room next door.

Marie-Grace could hear Annabelle’s baby sister crying. She guessed that Mrs. Rumsford was glad to have help with Annabelle. “Let’s go,” said Marie-Grace, holding out her hand to the little girl.

Each stateroom on the Liberty had two doors. One led into the main cabin of the steamboat. The other door opened onto one of the galleries that ran along the outside of the boat like long balconies, overlooking the river. Marie-Grace opened the door to the gallery, and the girls stepped outside.

The Liberty was one of many boats docked along the busy, noisy New Orleans levee. Other steamboats were already sailing on the river, along with rafts, small fishing boats, and some old-fashioned flatboats loaded with cargo. Soon we’ll be on our way, too, thought Marie-Grace with a thrill of anticipation.

She’d been on the Mississippi River before, when she had traveled with Uncle Luc and Aunt Océane to visit family. That had been a wonderful trip, but they had sailed only a short way. On this trip, Marie-Grace and her father were going to travel all the way from New Orleans to Cairo, Illinois. From Cairo, they would take another steamboat up the Ohio River to Pennsylvania, where they would visit old friends of Papa’s before returning to New Orleans.

When Marie-Grace had told Cécile about the trip, her friend had made her promise to write as often as she could. “Tell me all about your adventures!” she’d urged Marie-Grace.

Marie-Grace had hesitated. “What if nothing exciting happens?”

“Oh, something will!” Cécile had insisted with her usual confidence. “Just don’t forget to write me about it.”

Now as she and Annabelle walked toward the open promenade area at the front of the steamboat, Marie-Grace decided that she would tell her friend all about the Liberty. I bet Cécile’s never been on a boat this big either, she thought.

The steam engines on the Liberty powered two huge paddle wheels, one on the starboard or right side of the boat, the other on the port or left side. The magnificent boat was painted white with blue trim. It had three full decks and a pair of tall smokestacks that rose high into the sky.

When she and Papa had arrived on the Liberty, Marie-Grace had seen that each of the steamboat’s decks was very different. The first or main deck was crowded with cargo. Lots of people were on this deck, too. Some were crew members who were busy hauling crates and sacks and barrels on board. Others were passengers who traveled on the main deck, even though there were no staterooms or sleeping berths on this level. The main-deck passengers were able to get cheap tickets because they slept amid the cargo or on the open deck during the entire trip.

The middle deck was called the boiler deck, and it was much fancier. Passengers paid more for their tickets, but they had private staterooms with comfortable beds. There were carved guardrails along the outside of the boiler deck, and passengers could sit or stroll along the galleries. Stateroom passengers, like Marie-Grace and her father, also enjoyed meals in the steamboat’s elegant main cabin.

The boat’s captain, two pilots, and other officers had their living quarters on the hurricane deck, which was above the boiler deck. Perched at the top of the Liberty was the pilothouse, where the steamboat’s pilots steered the huge boat.

This afternoon, Captain Obadiah Smith was standing with a dozen or so passengers on the boiler deck, watching the cargo being loaded on the main deck below. Mr. Stevenson, one of the pilots, was on the deck, too, along with Marie-Grace’s father, Dr. Thaddeus Gardner. Mr. Stevenson was a friend of Papa’s. Last summer, Dr. Gardner had taken care of Mr. Stevenson’s son when the boy had become sick with yellow fever, the terrible disease that had killed so many people in New Orleans.

Papa had worked long hours during the yellow fever epidemic, and he had often treated patients at Charity Hospital. Two nuns who were traveling on the Liberty had worked at the hospital, too, and they greeted Papa as an old friend. Sister Catherine was a tiny, talkative woman, and Sister Frederica was tall and quiet.

While the grown-ups chatted, Marie-Grace and Annabelle took up positions at the front deck rail. Marie-Grace handed Annabelle several small chunks of bread. “When I say ‘three,’ throw the bread as far as you can!” Marie-Grace reminded her. “One, two, THREE!”

Both girls tossed their bread to the birds. Squawking, the birds eagerly dived for the chunks. Annabelle giggled. “Let’s do that again!”

Mrs. Rumsford, with her baby in her arms, came out on deck as the gulls snapped up the last crumbs of bread. Mrs. Rumsford gave Marie-Grace a smile of thanks. Then she called, “Come, Annabelle. We’ll walk the baby out here for a bit.”

As Annabelle ran to join her mother, Marie-Grace looked out over the railing toward New Orleans. She could see the spires of St. Louis Cathedral, and even though she was excited about the trip, she felt a pang of sadness at leaving the city. She knew that in the weeks she would be away, she would miss her home, her dog Argos, and all her friends, especially Cécile.

An early spring breeze was blowing as Marie-Grace watched the crowds of people on the shore. Men in dark suits and ladies in bright dresses were hurrying along the levee, rushing to catch boats. Street vendors were crying out the goods they had for sale, and carriage drivers were calling to their horses. Laborers were shouting as they carried cargo to and from the boats. Newly arrived immigrants were clustered along the levee, too, many talking in foreign languages.

Above all the noise came the sound of an old man’s voice. He was standing by the Liberty’s gangplank, arguing with two crew members. A girl in a brown dress stood near the man, and behind her, porters carried two large trunks. I wonder what’s happening? Marie-Grace thought as the steamboat’s bell clanged again.

The elderly man called up to the captain in French-accented English. “May I have a word with you, sir?”

Captain Smith, a tall man with steel-gray hair and thick gray eyebrows, was smoking a pipe. He nodded to the two men at the gangplank, and the crew members stepped aside to allow the new arrivals aboard.

As Marie-Grace and the other passengers looked on curiously, the elderly man came puffing up the stairs from the main deck, followed by the girl and the porters. The man had white hair and a kind face. He introduced himself to Captain Smith as Monsieur LaPlante, owner of a small hotel on Canal Street.

Monsieur LaPlante gestured to the girl. “This young lady is Wilhelmina Newman. Her father was staying at my hotel but, very sadly, he died a few days ago. Now she must travel back to her grandmother in New Madrid, Missouri. Your steamboat will stop there, won’t it?”

“Yes,” Captain Smith said. He tapped his pipe on the railing. “Does she have a ticket for a stateroom?”

Monsieur LaPlante looked concerned. “Well, the child came to New Orleans as a deck passenger.” He gestured to the main deck below. “Could she not travel back on your deck? She has very little money, but she must get back to her home as soon as it can be arranged.”

“The deck is no place for a child traveling alone,” said the captain. “Besides, most of those passengers have just come from Europe and hardly speak English.” Captain Smith shook his head. “If the girl does not have family or friends with her, she’ll need a ticket for a stateroom.”

“Ah, what a shame!” said Monsieur LaPlante, his shoulders slumping in defeat. “She has no one to take her home. I was told that you were a charitable man and might help the child.”

Wilhelmina stepped out from behind Monsieur LaPlante. She was very thin, with red hair and pale skin. She looked tired, but she spoke out boldly. “My ma was German, and I speak a bit of German, too. I could manage all right on the deck.”

She said her mother was German, Marie-Grace realized. So both of her parents have passed away. Marie-Grace’s own mother had died several years ago, and her heart went out to the girl. What would it be like for Wilhelmina to travel all by herself? Marie-Grace wondered. Wilhelmina was wearing a faded brown calico dress with only a light shawl. Surely she’d be cold on deck. If only there was another place for her to sleep…

With a start, Marie-Grace remembered the extra bed in her tiny stateroom. For a moment, she hesitated. She was shy, and this girl didn’t seem very friendly. But how would I feel if I was in her place? Marie-Grace wondered. She decided to take a chance. “Wilhelmina can stay with me,” she offered quietly.

Captain Smith turned to Marie-Grace. “What did you say?”

Suddenly, everyone was looking at Marie-Grace. She felt her face blush bright red, but forced herself to speak louder this time. “Wilhelmina could share my stateroom,” she told the captain. “I wouldn’t mind at all.”

“What a good idea!” exclaimed one of the passengers. She was a plump woman in a cranberry-colored dress, and she looked at Wilhelmina pityingly. “The child would be much better off in a stateroom.”

“It would be an act of charity to take her back to her family,” added Sister Catherine, and Sister Frederica nodded in agreement.

Wilhelmina scowled at them. “I’m not a child,” she said, lifting her chin. “I turned eleven last month. And I don’t want charity—just passage home.”

She’s my age, thought Marie-Grace. It would be nice to have someone besides Annabelle to talk to. “It wouldn’t be charity. I’d like company,” Marie-Grace said quickly. “There’s an extra bed in my stateroom, too.”

Captain Smith tapped his pipe again. “We can find a place for your trunks down on the main deck,” he told Wilhelmina. “And if Miss Gardner is willing to share her stateroom, you can travel for free.”

Wilhelmina’s eyes widened. “I need to have both my trunks with me.”

“Her father left those trunks for her,” Monsieur LaPlante explained.

The captain frowned at the pair of trunks. One was old and caked with dirt. The other was smaller and had shiny brass fittings and a bright brass lock. “There isn’t room for both those trunks in the stateroom,” he said flatly. He pointed to the smaller one. “You can keep that one, and we’ll put the other one with the cargo. We’re leaving in a few minutes, so decide whether you want to stay here or come with us.”

Dr. Gardner looked at Wilhelmina with concern. “I urge you to accept Captain Smith’s offer,” he said.

“Indeed, it’s a generous offer, child. You could travel back in comfort,” Monsieur LaPlante said. “And if you don’t leave now, we’ll have to find someone else to take you back to your family.” The old man wiped his brow. “I don’t know how long that will take.”

“But I have to get home now!” Wilhelmina protested. She looked even paler than before, and she seemed unsteady on her feet.

“Are you feeling ill?” Marie-Grace asked, reaching out a hand to her.

“I’m fine,” declared Wilhelmina. She brushed Marie-Grace’s hand away. “I guess I’ll come with you, but…” She closed her eyes and rubbed her forehead. “I, um…” Wilhelmina’s face turned a sickly shade of white. Then she collapsed in a heap onto the deck.