Читать книгу Entanglement - Sarah Nuttall - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

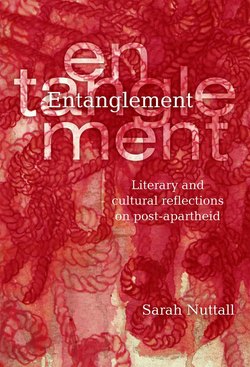

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Entanglement is a condition of being twisted together or entwined, involved with; it speaks of an intimacy gained, even if it was resisted, or ignored or uninvited. It is a term which may gesture towards a relationship or set of social relationships that is complicated, ensnaring, in a tangle, but which also implies a human foldedness.1 It works with difference and sameness but also with their limits, their predicaments, their moments of complication. It is a concept I find deeply suggestive for the kinds of arguments I want to make in relation to the post-apartheid present, in particular its literary and cultural formations. So often the story of post-apartheid has been told within the register of difference – frequently for good reason, but often, too, ignoring the intricate overlaps that mark the present and, at times, and in important ways, the past, as well.

Entanglement is an idea that has been explored by scholars in anthropology, history, sociology and literary studies, although always briefly and in passing rather than as a structuring concept in their work. I want to draw it from the wings and place it where we can see it more clearly, and consider that it might speak with a tongue more fertile than we had imagined, with nuances often uncaught or left latent in what may constitute a critical underneath, or sub-terrain. In the South African context which I will examine here, the term carries perhaps its most profound possibilities in relation to race – racial entanglement – but it brings with it, too, other registers, ways of being, modes of identity-making and of material life.

Below I outline six ways in which the term has been interpreted, explicitly or implicitly, by others. I spend some time on this, since these are complex ideas, ideas which signal a number of important intellectual pathways forged in recent years in African studies and beyond. Thereafter, I explain how I think of the term, bringing to it my own inflections, and explaining why it is an appropriate structuring idea for the book as a whole.

The first rubric under which the term has been used is in relation to a process of historical entanglement. As early as 1957 the liberal historian, C W de Kiewiet (1957), suggested that the deepest truth of South African history, and one often elided by later historians, is that the more dispossession occurred the more blacks and whites depended on each other. There was an intricate entanglement on the earliest colonial frontiers: accompanying whites’ search for land was the process of acquiring labour and, in this process, whites became dependent on blacks, and blacks on whites. Precisely as this dependency grew, so whites tried to preserve their difference through ideology – racism. The implications of De Kiewiet’s argument (p 48) that ‘the conflict of black and white was fed more by their similarities than by their differences’ is that the emergence and articulation of racial difference was, in this context, a symptom of loss (loss of independence through increasing dependence on black labour) – but a loss that most whites on the early frontier refused to embrace.

Much more recently, Carolyn Hamilton (1998) has argued that categories and institutions forged under colonial rule should not be viewed as the wholesale creation of white authorities but as the result of ‘the complex historical entanglement of indigenous and colonial concepts’ (pp 3-4). By focusing on how disparate concerns were drawn together and, over time, became entangled, this approach enables us to elucidate the diverse and shifting interests that fuelled colonial politics, and to reveal that it was never simply about colonial subjugation and anti-colonial resistance. Rather, it entailed the uneven mixing and reformulation of local and imperial concerns. Lynn Thomas’s (2003) work is part of a growing literature, mainly focused on medicine and domesticity, that analyses the history of the body in Africa as a story of wide-ranging struggles over wealth, health and power – and how such struggles connected and combined the material and the moral, the indigenous and the imperial, the intimate and the global. Thomas’s work on reproduction and the politics of the womb in Kenya emphasises entanglement as against two earlier approaches to the topic: the first, she shows, is the ‘breakdown of tradition’ approach, which sees colonialism as a clash of two radically different worldviews, one African and one European, resulting in the ultimate triumph of the latter (such arguments resonate with social scientific theories of ‘modernisation’). The second emphasises the power of colonial discourses and categories, largely at the expense of exploring the impact of colonialism on its subjects, and the perspectives and experiences of colonial subjects (pp 17-19).

Isabel Hofmeyr (2004), in her work on the history of the book, argues that rigid distinctions between ‘metropole’ and ‘colony’ are increasingly misleading. Unravelling the simplifying dualisms of ‘centre/periphery’ and ‘colonised/coloniser’ Hofmeyr weaves, instead, an imaginary structured by circuits, layering, webs, overlapping fields and transnational networks. Texts, like identities, do not, she argues (p 30), travel one way – from centre to periphery, for instance – but in ‘bits and pieces’ and through many media, transforming in many settings and places, and convening numerous different publics at different points in what Appadurai (1986) has referred to as their ‘social lives’.

Hofmeyr is interested in diasporic histories, moving between Africa, the Caribbean, Europe and the United States, and her work constitutes a web versus an avowedly national intellectual formation. Hofmeyr’s web, carrying with it the notion of interlacing, an intricacy of pattern or circumstance, a membrane that connects, is an entanglement of historical space and time. If she looks at shared fields of discourse and exchange, at ‘intellectual convergences’ (p 17), she also considers the conditions under which such formations are rejected, terminated or evaporate, becoming ‘meaningless or unintelligible’ (p 15). In this case, modes of translatability and entanglement become short-lived, spectral.

The second major rubric invoking the term is temporal. Achille Mbembe (2001, p 14) has written about the time of entanglement, arguing that, as an age, the postcolony ‘encloses multiple durées made up of discontinuities, reversals, inertias, and swings that overlay one another, interpenetrate one another: an entanglement’. Mbembe argues that there is no way to give a plausible account of the time of entanglement without asserting three postulates: firstly, that this time is ‘not a series but an interlocking of presents, pasts and futures that retain their depths of other presents, pasts and futures, each age bearing, altering and maintaining the previous ones’. Secondly, that it is made up of ‘disturbances, of a bundle of unforeseen events’. Thirdly, that close attention to ‘its real patterns of ebbs and flows shows that this time is not irreversible’ (and thus calls into question the hypothesis of stability and rupture underpinning social theory) (p 16).

To focus on the time of entanglement, Mbembe shows, is to repudiate not only linear models but the ignorance that they maintain and the extremism to which they have repeatedly given rise. Research on Africa has ‘assimilated all non-linearity to chaos’ and ‘underestimated the fact that one characteristic of African societies over the long durée has been that they follow a great variety of temporal trajectories and a wide range of swings only reducible to an analysis in terms of convergent or divergent evolution at the cost of an extraordinary impoverishment of reality’ (p 17)2.

Jennifer Wenzel’s work (2009) also contributes to a theory of entanglement in its temporal dimensions. She traces the afterlives of anti-colonial millenarian movements as they are revived and revised in later nationalist struggles, with a particular focus on the Xhosa cattle-killing in South Africa. In seeking to understand literary and cultural texts as sites in which the unrealised visions of anti-colonial projects continue to assert their power, she rethinks the notion of failure by working with ideas of ‘unfailure’ to examine the tension between hope and despair, the refusal ‘to forget what has never been’ of which these movements speak. Wenzel explores ways of thinking about failure other than falsity, fraudulence or finality – that is, in terms of historical logics other than decisive failure as a dead end. Failure, she suggests, might involve a more complex temporality, and the afterlife of failed prophecy might take forms other than a representation of failure. It may be read, for instance, in terms of a ‘utopian surplus’ that sees in failed prophecy unrealised dreams that might aid in the imagining of contemporary desires for liberation. Thus Wenzel proposes an ethics of retrospection that would maintain a radical openness to the past and its visions of the future.

Literary scholars have attended to a rubric of entanglement in terms of two formulations in particular: ideas of the seam, and of complicity. Leon de Kock (2004) proposes that we read the South African cultural field according to a configuration of ‘the seam’. He takes the notion of the ‘seam’ initially from Noel Mostert, author of Frontiers (1993), who writes that ‘if there is a hemispheric seam to the world, between Occident and Orient, then it must lie along the eastern seaboard of Africa’ (p xv). While the seam remains embedded in the topos of the frontier, De Kock draws it into his analysis to mark ‘the representational dimension of cross-border contact’ (p 12). For De Kock the seam is the place where difference and sameness are hitched together – where they are brought to self-awareness, denied, or displaced into third terms: ‘a place of simultaneous convergence and divergence, the seam is the paradox qualifying any attempt to imagine organicism or unity’ (p 12).

De Kock gives a poststructuralist spin to Mostert’s historical account, grounding its tropes within the discourse of postcolonial theory. He does so to mount a reading of race and difference in South Africa – especially the deconstruction of a system of white superiority as a political and epistemological ground. The configuration of the seam remains, in his reading, embedded in the idea of the frontier, as do contemporary race relations in South Africa. Suggesting that the post-apartheid present is engaged in an attempt to suppress difference, he professes an ‘ingrained weariness’ with ‘unitary representation’ (p 20). It is striking that the greatest subtlety of De Kock’s analysis is reserved for the past (such as his reading of Sol Plaatje’s simulation of sameness within the colonial project in order to achieve the objective of political equality, in a terrain he well understood to be riven with difference), and his bibliography attests to only a minimal engagement with the sources of the ‘now’. What De Kock characterises as the recurrent ‘crisis of inscription’ that defines South African writing, Michael Titlestad (2004a) wants to consider as improvising at the seam. Titlestad writes about the ways in which jazz music and reportage have been used in South Africa to construct identities that diverge from the fixed subjectivities constructed in terms of apartheid fantasies of social hierarchy. Jazz, because of both its history and its cultural associations, writes Titlestad, is persistently ‘a music at the seam’ (p 111).

The theoretical import of the notion of ‘complicity’ as a means of approaching the South African cultural archive has been given powerful expression by Mark Sanders (2002). Sanders argues that apartheid and its aftermath occasion the question of complicity, both in terms of glaring instances of collaboration or accommodation – in which he is less interested – and via a conception of resistance and collaboration as interrelated, as problems worth exploring without either simply ‘accusing or excusing’ the parties involved (p x). Sanders works from the premise that both apartheid’s opponents and its dissenting adherents found themselves implicated in its thinking and practices. He therefore argues that we cannot understand apartheid and its aftermath by focusing on apartness alone, we must also track interventions, marked by degrees of affirmation and disavowal, in a continuum of what he calls ‘human foldedness’. The South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) stages the question of complicity, he shows, by employing a vocabulary that generalises ethico-political responsibility (referring, for instance, to the ‘little perpetrator’ in each of us). Literature, too, he argues, stages the drama of the ‘little perpetrator’ in the self, calling upon a reader to assume responsibility for an other in the name of a generalised ‘foldedness in human-being’ (p 210).

Sanders employs a reading strategy which calls upon the reader to ‘acknowledge one’s occupation by the other, in its more and less aversive forms’ (p 210) – a strategy which draws out what is both most ‘troubling’ and most ‘enabling’ about human being(s) (p 18). Sanders argues that this manner of reading applies equally to texts we are accustomed to thinking of as ‘black resistance texts’. The question of complicity as a context for assuming responsibility is integral to black intellectual life and to the tasks that have faced black intellectuals, he argues, a point he goes on to demonstrate in readings of the work of Sol Plaatje, Bloke Modisane, A C Jordan and others. Such a reading strategy is one that is profoundly consonant with Sanders’s overall argument, in that it refuses in itself the stance of being ‘merely oppositional’. It has no choice but to project itself ‘beyond apartheid’. Sanders suggests a theory and a practice which are beyond apartness as such.

Sanders’s work draws on a complex interleaving of post-TRC debates in South Africa and debates in international scholarship about a reconstituted ethics. The TRC gave rise to, and publicly brought into being, the relation of self to other as an ethical basis for the post-apartheid polity. The focus globally on ethics in literary studies and other disciplines has been reinvigorated by Foucault’s revaluation of the category of the self, conceiving of the care of the self as an ethical project, combined with the emergence of Emmanuel Levinas as a model for literary-ethical inquiry. Whereas previously ethics was seen as a ‘master discourse’ that presumed a universal humanism and an ideal, autonomous and sovereign subject, and became a target of critique (the critique of humanism was the exposé of ethics), work drawing on Foucault and Levinas attempts to do ethics ‘otherwise’ (Garber et al 2000).3 Such work nevertheless leaves us with further questions about who accords a greater humanity, or ethical sensitivity, to whom, and the limits of that gesture. Sanders’s notion of complicity in its wide (rather than punitive) sense enables us to begin the work of thinking at the limits of apartness.

The fourth rubric I want to consider is an entanglement of people and things. Although Tim Burke (1996) does not use this particular term he argues that Marx’s definition of commodity fetishism does not leave sufficient room for the complexity of relations between things and people, nor for the imaginative possibilities and unexpected consequences of commodification, or the intricate emotional and intellectual investments made by individuals within commodity culture. Bill Brown (2003) has argued that cultural theory and literary criticism require a comparably new idiom, beginning with the effort to think with or through the physical object world, the effort to establish a genuine sense of things that comprise the stage on which human action, including the action of thought, unfolds. He concedes a new historicist desire to ‘make contact with the real’4 but more than this, he wishes to locate an approach which reads ‘like a grittier, materialist phenomenology of everyday life, a result that might somehow arrest language’s wish, as described by Michael Serrès (1987, p 111), that “the whole world … derive from language”’.5 Brown tells a tale of possession – of being possessed by possessions – and suggests that this amounts to ‘something stranger’ (p 5) than the history of a culture of consumption. It is not just a case of the way commodity relations come to saturate everyday life but the human investment in the physical object world and the mutual constitution, or entanglement, of human subject and inanimate object. He aims to sacrifice the clarity of thinking about things as objects of consumption in order to see how our relation to things cannot be explained by the cultural logic of capitalism. He makes the case for a kind of possession that is irreducible to ownership (p 13). This is a relatively new field of work that has only just begun to surface, but one I want to bear in mind in relation to several of the chapters which follow.

While each of the four rubrics of entanglement explored above takes us a considerable way towards a critique of an over-emphasis on difference in much of the scholarship produced within African and postcolonial studies in recent decades, none of them considers the new frontier of DNA research. The fifth rubric worth consideration here has to do with the implications of the DNA signature. New attention has been paid globally and in post-apartheid South Africa to the fact that tracing the ‘maternal’ and ‘paternal’ genetic lines visible on each individual’s X and Y chromosomes allows scientists to generate ‘ancestral maps’ charting the geographical location of ancestors closer to us in time. Identities suggested by ancestral DNA signatures undercut the rigid conceptions of racial identity in which both colonial rule and apartheid were based.

Kerry Bystrom (2007) has reported in her work how renowned satirist Pieter-Dirk Uys, classified as white under apartheid, learned that he had a maternal line African gene. His response was: ‘That’s really nice. So I’m an African. No people with black skin can point a finger at me.’ With his typically sharp sense of irony and wit, Uys, as Bystrom points out, ‘puts his finger on what is simultaneously wonderful and troubling about the ways in which “African” identity can be expanded through genetic and familial mapping’. This new version of the evolutionary family story both provides biological legitimation for racial equality and opens up ways to conceptualise a non-racial South African identity. On the other hand, as Bystrom points out, there is a way in which, as Uys’s comment forces us to consider, the project of defining a broadly inclusive genetic South African identity risks effacing the divisions entrenched, and legislated for, by apartheid. Entanglement, as suggested within this discourse, is both productive and reductive. The DNA debate does the work of de-familiarisation: it has the ability, as Bystrom writes, to ‘render the familiar strange and the strange familiar’.

This brings me to the final rubric I want to consider here, one which has been implicit in some of what has been discussed above but which requires explicit elucidation, and that is the notion of racial entanglement. In the late 1970s Eduard Glissant, reflecting on the issue of race, identity and belonging in the Caribbean (1992), used the term entanglement to refer to the ‘point of difficulty’ of creolised beginnings. ‘We must return,’ he wrote, ‘to the point from which we started, not a return to the longing for origins, to some immutable state of Being, but a return to the point of entanglement, from which we were forcefully turned away; that is where we must ultimately put to work the forces of creolization, or perish (p 26).6

Globally the 1990s gave rise to a new focus on race and ethnicity, falling largely within two contending lines of thought. The first strand, widely known as critical race studies, paid renewed attention to racism and identity. It focused on ‘hidden, invisible forms of racist expression and well-established patterns of racist exclusion that remain unaddressed and uncompensated for, structurally marking opportunities and access, patterns of income and wealth, privilege and relative power’ (Essed & Goldberg 2002, p 4). ‘Critical race studies’ finds institutional racism, patterns of racial exclusion, and structurally marked patterns of access as prevalent as before, if not more so. Such work draws on the writings of Du Bois, Fanon, Carmichael, Gramsci, Davis, Carby and Roediger, among many others, to articulate the nature of racial hegemony in the contemporary world, but especially in the United States.

A second, contrasting, strand of race studies approached the contemporary question of race in a manner which takes us closer to the idea of entanglement. For Paul Gilroy (2000) racial markers are not immutable in time and space. Gilroy, like a number of writers before him, including Fanon and Said, has argued for a humanism conceived explicitly as a response to the sufferings that racism and ‘race thinking’ have wrought. He argues that in the 21st century race politics and anti-racist laws have not created an equal society and that what is needed in response is a re-articulation of an anti-racist vision – as a politics in itself. In his view, the most valuable resources for the elaboration of such a humanism derive from ‘a principled, cross-cultural approach to the history and literature of extreme situations in which the boundaries of what it means to be human were being negotiated and tested minute by minute, day by day’ (p 87).

In more recent work, Gilroy (2004) has drawn on the resources of a vibrant and complex ‘multiculture’ in both Britain and the United States to reveal an alternative discourse of race already at work in contemporary life. In their work on whiteness, Vron Ware and Les Back challenge a discourse of ‘separate worlds’, which, in their view, structures so much contemporary thinking about race (especially in the United States), finding it to be a ‘bleak formula’, a prepackaged view of the world which suggests that ‘how you look largely determines how you see’ (p 17). What difference does it make, they ask, when people in societies structured according to racial dominance turn away from the privilege inherent in whiteness? Or when the anti-race act is performed, by whom, and in whose company?

John Hartigan (1999) argues that public debate and scholarly discussion on the subject of race are burdened by allegorical tendencies (he writes about the United States, but much of what he says refers directly to South Africa too). Abstract racial figures, he writes, ‘dominate our thinking, each condensing the specificities of peoples’ lives into strictly delimited categories – “whites and blacks” to name the most obvious’.

Given the national stage on which the dramas of race unfold, certain broad readings of racial groups across the country are warranted, Hartigan concedes. But as such spectacles ‘come to represent the meaning of race relations, they obscure the many complex encounters, exchanges and avoidances that constitute the persistent significance of race in the United States’ (p 3). On the one hand, social researchers grapple with the enduring effect of racism and rely on the figures of ‘whites’ and ‘blacks’ to do this; on the other, they argue, unconvincingly, it seems, that races are mere social constructs. ‘How are we to effect a change in Americans’ tendency to view social life through a lens of “black and white” when we rely upon and reproduce the same categories in our analyses and critiques of the way race matters in this country?,’ he asks (p 3). The argument here is that we can loosen the powerful hold of the cultural figures of ‘whites’ and ‘blacks’ by challenging the economy of meaning they maintain. That is, by grasping the instances and situations in which the significance of race spills out of the routinised confines of these absolute figures, we can begin to rethink the institutionalisation of racial difference and similarity.

In South African literary and cultural scholarship there has been, since the mid-1990s, a departure from earlier work in which race was largely left unproblematised and was treated as a given category in which difference was essentialised. Such work had focused, like the anti-apartheid movement itself, on fighting legalised and institutionalised racism rather than on analysing the making of racial identity per se. In more recent work, however, there has been an insistence on race in order to deconstruct it (Steyn 2001; Distiller & Steyn 2004; Erasmus 2001; Ebrahim-Vally 2001). Thus Distiller & Steyn, in their book Under Construction: ‘Race’ and Identity in South Africa Today, aim to address the ‘need for a vocabulary of race in South Africa today’ (p 2) and to ‘challenge the artificiality of “whiteness” and “blackness” and to explore the implications of an insistence on policing their boundaries and borders’ (p 7). Significantly, the first South African academic conference dedicated to the issue of race took place only in 2001, co-hosted by the newly formed Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WISER) and the Wits History Workshop, and entitled ‘The Burden of Race’.

These, then, are some of the ways in which the term entanglement has been used by scholars, or indirectly suggested in their work. I draw strongly on them in the chapters that follow. Although I frame them in my own analytical grammar, each carries traces of the above articulation by other scholars. Entanglement offers, for me, a rubric in terms of which we can begin to meet the challenge of the ‘after apartheid’. It is a means by which to draw into our analyses those sites in which what was once thought of as separate – identities, spaces, histories – come together or find points of intersection in unexpected ways. It is an idea which signals largely unexplored terrains of mutuality, wrought from a common, though often coercive and confrontational, experience. It enables a complex temporality of past, present and future; one which points away from a time of resistance towards a more ambivalent moment in which the time of potential, both latent and actively surfacing in South Africa, exists in complex tandem with new kinds of closure and opposition. It also signals a move away from an apartheid optic and temporal lens towards one which reifies neither the past nor the exceptionality of South African life.

A focus on entanglement in part speaks to the need for a utopian horizon, while always being profoundly mindful of what is actually going on. Such a horizon carries particular weight in societies which confront the precariousness of life, crime, poverty, AIDS and violence on a daily basis; it suggests the importance, too, of holding ‘heretical conversations’ in order to question and even, at times, dislodge or supersede the tropes and analytical foci which quickly harden into conventions of how we read the ‘now’. So, too, reading through entanglement makes it necessary to find registers for writing about South Africa that enable properly trans-national conversations.

Entanglement, as I use it in the chapters which follow, enables us to work with the idea that the more racial boundaries are erected and legislated the more we have to look for the transgressions without which everyday life for oppressor and oppressed would have been impossible. It helps us, too, to find a method of reading which is about a set of relations, some of them conscious but many of them unconscious, which occur between people who most of the time try to define themselves as different.

Entanglement, furthermore, returns us to a concept of the human where we do not necessarily expect to find it. It enables an interrogation, imperatively, of the counter-racist and the work of desegregation. Since the chapters which follow take up these issues from the vantage point of South Africa they enable a conversation with preoccupations in contemporary humanities scholarship elsewhere, and reveal aspects of what South Africa can contribute to global debates about identity, power and race. Entanglement provides a suggestive way to draw together these theoretical threads. It is an idea I draw on throughout the book, without underestimating, I hope, what makes people different, how they think they are different (even when they might not be), and how difference has a charged and volatile history in this country.

The first chapter seeks a defamiliarising way of reading the historical and contemporary South African cultural archive by employing a lens of entanglement. One of the aspects the chapter explores is the possibilities and limits of an Anglicised and Africanised category of the creole. Within the larger rubric of entanglement it places a specific emphasis on how to come to terms with a legacy of violence in a society based on inequality, drawing on creolisation’s own origins within the historical experience of slavery and its aftermath. It goes on to re-examine, in the light of this initial discussion, regional variations and the implications for how we read race and class in South Africa.

The chapter moves away from what Hofmeyr (2005) has referred to as the ‘hydraulic models of domination and resistance’ traversing neo-Marxist and nationalist accounts towards a project of making ‘the ambiguous networks and trajectories of the postcolonial state legible’ (p 130). It looks for analytical formations which increasingly inscribe South African life into a body of work done elsewhere on the continent, especially Mbembe’s (1993) idea that oppressor and oppressed do not inhabit incommensurate spheres: rather, that they share the same episteme. It moves across disciplines, searching for disturbances, fluctuations, oscillations in conventional accounts, looking for configurations of space, identity, race and class usually left unexpressed, and dormant.

In Chapter Two, entitled ‘Literary City’, I write about ways in which Johannesburg is emerging in recent city fiction. I explore, that is, notions of entanglement from the vantage point of city life and city forms, of the making of citiness in writing. ‘Citiness’ refers to modes of being and acting in the city as city and it encompasses histories of violence, loss and xenophobia as well as those of experimentation and desegregation.

My aim in the chapter is to explore the modes of metropolitan life – the ‘infrastructures’ – which come to light in contemporary fiction of the city. These infrastructures include the street, the café, the suburb and the campus – assemblages of citiness in which fictional life worlds intersect with the actual, material rebuilding of the post-apartheid city. I explore some of the figures to which these urban infrastructures give rise: the stranger, the aging white man, the suburban socialite, the hustler.

Of particular interest is what the metropolitan form can offer, via its fictional texts, in relation to the remaking of race. To what kinds of separation and connectedness does it give rise? In what ways, if at all, does it exceed the metaphors of race and the binaries to which it gives rise and how, as Helgesson (2006) puts it, do characters move through and across long-established representational regimes? Citiness in Johannesburg, I argue, is an intricate entanglement of éclat and sombreness, light and darkness, comprehension and bewilderment, polis and necropolis, desegregation and resegregation.

In Chapter Three I focus on autobiographies and related narratives of the self written by whites from the mid-1990s onwards, a period which, in my view, marks a major shift in the ways in which whiteness began to be looked at as the embeddedness of race in the legal and political fabric of South Africa started to crack.

The chapter, entitled ‘Secrets and Lies’, develops a set of arguments around, on the one hand, looking and watching, modes which appear to inhabit certain versions of ‘unofficial’ whiteness (the act of watching others watching the self, for instance) but on the other, and more predominantly, around the secrets and sometimes the lies, which inhabit the negotiation of whiteness. In almost all the bodies of work considered confronting one’s whiteness is also confronting one’s secret life, including the untruths – latent, blatant, imminent, potent – that inhabit the white self.

The chapter aims to offer an alternative route through the South African archive of whiteness by attending to what I have called its ‘unofficial’ versions, within a context of long-held racist assumptions and practices. Thus it considers some of the resources available in South African society to crack open the discourses of whiteness, and therefore blackness, in the context of ‘the now’. It also aims to show the complexity of these unofficial versions, revealing their largely under-researched duplicity, uncertainty, vulnerability: their secret life.

Chapter Four, ‘Surface and Underneath’, is written in two parts. It takes as its defining idea the notion of Johannesburg as a city with a surface and an underneath. The early part of the chapter explores this concept, suggesting its historical, psychic and hermeneutic dimensions. In broad terms, we might consider this a city in which the ‘surfaces’ of a highly developed industrialised capitalist economy and its attendant set of media cultures are entangled with a subliminal memory of life below the surface – a history of labour repression based on a racial hierarchy; of alienation, but also of insurrection.

If the surface and underneath are part of the historical and psychic life of the city they also finds expression in its literary and cultural formations. The first section focuses on Ivan Vladislavič’s account of living in Johannesburg, Portrait with Keys (2006), and then on two texts by young black South African writers, both published in 2007, which both focus on the concept of the ‘coconut’. The ‘coconut’, a pervasive shorthand for a person who is ‘black on the outside but white on the inside’, also relies on the metaphor of a surface and an underneath and tells us something important about current framings of cross-racial life in the city. In the second part I consider a series of paintings by Johannesburg artist Penny Siopis, known as the Pinky Pinky series. While her work has been read almost exclusively within the register of trauma, I argue that the series reveals a new capaciousness in her figuring of urban life and the desires it produces. Siopis turns her attention to the surface as a painterly and analytical space, and the series suggests the emergence, if tentative, of a more horizontal or spliced mode of reading.

Chapter Five tries to capture something of the immense coincidence, so tangible in Johannesburg at present, between the end of apartheid and the rise of new media culture and cultures of consumption. The chapter, called ‘Self-Styling’, aims to show how we might take the surface more seriously in our analyses of contemporary cultural form even where contemporary youth media cultural forms in Johannesburg still signal to and cite the underneath of an apartheid past. In the first part I explore the rise of a youth cultural form widely known as ‘Y Culture’. Y Culture, also known as loxion kulcha, is an emergent youth culture in Johannesburg which moves across various media forms and generates a ‘compositional remixing’ that signals an emergent politics of style, shifting the emphasis away from an earlier era’s resistance politics. It is a culture of the hip bucolic which works across a series of surfaces in order to produce enigmatic and divergent styles of self-making. In the second part I consider a recent set of advertisements that have appeared on billboards and in magazines in the wake of Y Culture, showing how they simultaneously engage with and push in unexpected directions one of the most striking aspects of Y/ loxion culture, an attempt to reread race in the city. In analysing the advertisements I consider ways in which commodity images, and the market itself, produce re-imaginings of race in the city. How to read these commodified versions of entanglement (which are embedded in a much longer history of consumption and its media forms in this country) and what they can tell us about the remaking, or otherwise, of race in the city, is a question the chapter works with in its concluding section.

Chapter Six – ‘Girl Bodies’ – turns to issues of sexuality, and, in particular, to child rape. The chapter draws on an anecdote of a kind: an image, accompanied by a short text in a newspaper, to consider a subject left largely aside in earlier chapters: the question of gender and sexuality in the making of South Africa’s political transition, and of the violence which has emerged, somewhat spectacularly, into the post-apartheid public sphere.7

My account, which is written in the first person, focuses on the manufacture of anti-rape devices for girls and women – new technologies of the sexualised body. Through the telling of a story I explore how technology itself assigns changing meanings to the domains of the public and the private. I draw out, in the chapter, common interest – and trust in technology – among women from different race and ethnic groups – black and white, Tswana and Afrikaner. I explore sets of fantasies about technological solutions in relation to the body which are currently circulating globally but which take on radically local inflections. The chapter considers forms of re-segregation in a wider context of desegregation, and how re-segregation can be based on cross-racial complicities of a kind in a ‘post-racist’ context. In this chapter I subject a notion of entanglement to its limits, while also examining its most disturbing connotations. Examining the concept from the perspective of its outer edges helps to strengthen our understanding of how it works, where it can be useful, and what aporias we need to be alert to.

The chapters draw on a range of critical and writerly vocabularies. They include that which lies dormant in our analysis most of the time, that which offers a singular versus a general view, and the force of the anecdotal, a register of the unexpected in critical orthodoxies. In doing so, they capture something, I hope, of the complex trajectories of change in South Africa, at the level of content but also of form. In what follows I have wanted to speak about the politics of change as well as the ideas and experiences of self which underlie the social; the potential of metropolitan life as well as its foreclosures; the life of the body as well as the mind; cultures of the city as well as feudal imaginaries of the heartland; legacies, as well as contemporary practices, of racial and sexual violence. Put differently, this book explores ways we find of living together, of occupying the city, secrets we keep or tell, the life of the body, our desire for things, the darkness of sex.