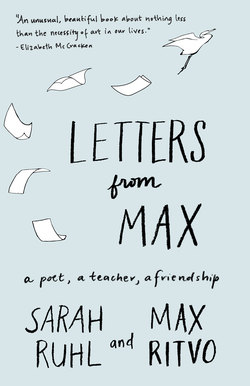

Читать книгу Letters from Max - Sarah Ruhl - Страница 57

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThat fall, Max moved to New York and entered Columbia’s MFA program in poetry. He wrote poems like water while undergoing chemotherapy.

Our letters now take on the familiar quality of spontaneous logistical wrangling because we saw each other more often—they are more in the vein of:

From me: “I know you like Halloween. We are having a Halloween party if you want to hang out with kids and see spooky movies.” And from Max: “OooOOO Halloween party.” Then small missives about my kids: “Spent Halloween with my William and his best pal Annabel, both dressed as Peter Pan, shouting: ‘Pixie dust away!’ And running down the street.” There would be invitations, like “Do you want tickets to my play?” And from Max: “Read a poem with me at my poetry reading on Thirteenth Street?” Or, from me: “Want to eat this weird mushroom soup that is supposed to help with lung cancer? I’ll go to Chinatown and buy the mushrooms and cook it.” Or: “Send me poems! I’m driving around in a minivan with three kids so need poems like water.” Or, from Max: “What is a hinky-pinky for Infinite-Rainbow Guitar Pick?” “Spectrum Plectrum.” (Hinky-Pinky is a rhyming game I played when I was little.) Or, quite often, from me: “The kids all have strep, I have to reschedule.”

I was busy, in and out of rehearsals for various projects. Conversations with Max were more often in real time over a meal and not in letters. They went something like this, over a slice of pizza:

SARAH:

How did it go to read your poetry out loud last night?

MAX:

It was good, it was nice, it was good of them to ask me. One poet read a poem and I said, “It’s funny, I can’t quite hear what you’re trying to get across because of the static in your poem.” And she said, “I’m not trying to get anything across, I don’t want you to get anything.”

SARAH:

I think that is sad.

MAX:

Yes, it is sad. She is trying to make language revert in on itself so it doesn’t communicate anything. Wittgenstein said the only thing that is left is silence and I think what he left out is that the only thing left is love.

SARAH:

Do you think love is silence?

MAX:

No, I don’t think so, I think love is relational and I think to understand the concept of love we always understand the idea that the person we love is trying to love us, so we understand intention. So I think there is this relational pocket of love that Wittgenstein is missing.

SARAH:

Like if you dropped Martin Buber’s I-Thou inside postmodernism—

MAX:

Yes—but I don’t know if you can put Buber inside of Wittgenstein.

SARAH:

When I was your age I walked into my professor’s office and said, “I don’t believe in postmodernism or deconstruction,” and she said, “Hmm, what all have you read about it?” and I said, “Hmm, maybe one book or two.” Terrible. Arrogant. But I still don’t believe in postmodernism.

MAX:

You don’t?

SARAH:

Do you?

MAX:

I do! Postmodernism devours everything, it eats everything, it acknowledges the void—

SARAH:

It has an appetite but no stomach!

MAX:

Yes, true—but it is the digestion of the fox and not the hedgehog—it can be playful and loving—for example, it can say, here is a coin from behind my ear, here is a pine cone from behind my ear, not HERE IS A DIALECTIC—

SARAH:

Okay, so it’s a victory of smallness against self-importance—

MAX:

Yes—

SARAH:

—but it’s so self-important!

MAX:

It can be.

SARAH:

You’re saying it’s against the totalizing impulse, it’s against Casaubon’s key to all the mysteries in Middlemarch.

MAX:

I haven’t read Middlemarch, I’m illiterate.

SARAH:

You’re hardly illiterate. My friend thought Middlemarch was about bunnies.

MAX:

That’s Watership Down, yes?

SARAH:

Anyway, I think the vision of postmodernism you describe is a new thing, it’s to be invented, it’s not postmodernism because it’s small and humble and loving, it could be called “loving postmodernism” or something—LPM—

MAX:

Yes, LPM—what is LPM?

SARAH:

It’s small incursions of meaning into the void—it has to do with smallness—

MAX:

Yes, and with luminous priorities—

SARAH:

Except I don’t even want postmodernism in the title because it only defines itself in the negative up against modernism, and I find that inherently nihilistic—

MAX:

It all goes back to the Holocaust and how can we deal with the void and still be a joyous mammal, what can we affirm in the face of the void—

SARAH:

Yes, but postmodernism is not affirmative, and the problem is that Heidegger and his cronies were Nazi sympathizers so they can void out history and that’s very convenient.

MAX:

But how do we deal with the void and meaninglessness? My two favorite songs are Nat King Cole’s “Smile” as in “smile while your heart’s breaking” and “Girls Just Want to Have Fun.”

SARAH:

Do you think “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” is a sad song or a happy song?

MAX:

Exactly.

Sometimes Max would text me to distract me from nervousness before I gave a public reading (I am a reluctant public speaker) or to enliven my commute to New Haven. These dialogues would go something like this:

SARAH:

I’m on the Amtrak quiet car, it’s like my fairy godmother.

MAX:

Is it godmotherish because it transforms into a magically civilized place? Maybe death is an Amtrak quiet car, then we’d both be right in a way.

SARAH:

Yes. But would we know anyone on the car? And who is the conductor?

MAX:

No, I think you don’t know anyone, but there are familiar dinner rolls.

SARAH:

That sounds sad. Are there books?

MAX:

And the conductor is a reticent beautiful Steve Jobs.

SARAH:

That made me laugh.

MAX:

Good.

I think when you die, you are a book so you can’t read any other books. Give me some brutal feedback on my new poem; it’s new so I’m afraid it isn’t any good.

SARAH:

Because I’m so brutal.

MAX:

You’re not brutal.

SARAH:

You haven’t seen me play ping-pong.

MAX:

Good Lord your dark side.

At my forty-first birthday party at Risotteria Melotti in the East Village, there was a large group of friends and family. Max came and we played the Noel Coward adverb game. It’s a game in which one person has to leave the room and the others decide on an adverb they will act out and have that person guess. Max had us all in stitches. Max gave me a tea mug with two fish on it. There was a lot of jollity that year. Max’s illness seemed at an arm’s length.

We sometimes had lunches on the Upper East Side. I would joke that the only good reasons to come to the Upper East Side from Brooklyn were biopsies, getting highlights, or lunch with Max. I sometimes wrote at the New York Society Library, not far from Max’s apartment. I would bury my nose in those old stacks until I disappeared enough to write a play. And sometimes I would emerge into the light and have lunch with Max.