Читать книгу The Prince Who Would Be King: The Life and Death of Henry Stuart - Sarah Fraser, Sarah Fraser - Страница 27

Henry’s Anglo-Scottish Family

ОглавлениеNONSUCH

James set up his son’s first permanent English home at Nonsuch Palace in Surrey. Built by Henry VIII for his son, the future Edward VI, Henry VIII demanded it rival the greatest French Renaissance palaces: there would be none such anywhere in the world. Six hundred and ninety-five carved stucco-duro panels decorated the facades and inner court of the palace. They extended over 850 feet long, rising from sixteen to nearly sixty feet high in places. Gods and goddesses lolled and chased each other across the walls. Soldiers in classical uniforms battled for their lives, frozen for ever in their moment of triumph or death.

The panels overlooking the gardens featured depictions from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Stucco-duro polished easily to a high marble-like sheen: Nonsuch dazzled in sunlight. Other scenes illustrated to the heir the duties of a Christian prince. One panel showed Henry VIII and Edward seated among gods and mythical heroes. Divinities watched over them, blessing the Tudor dynasty. All in all, it was the ‘single greatest work of artistic propaganda ever created in England’. James instinctively knew it was the right setting in which to nurture the first ever Prince of Wales of the united kingdoms. The king had given Nonsuch to the queen, as one of her royal palaces.

Topping the massed bulk of the octagonal towers at each corner of the southern facade, enormous white stone lions bore Prince Henry’s standard in their paws. Mouths frozen in a snarl, their fierce eyes followed Henry and his friends as they hunted, practised feats of arms on foot and horseback, readying themselves to defend, attack, defeat, rule. The boys chased each other through gardens laid out by the keeper of Nonsuch, Lord Lumley, around fountains where water squirted out of the goddess Diana’s nipples, and past tall marble obelisks with black onyx falcons perched on top. Amongst all the treasures, Lumley’s most prized possessions were his books. He had built up the greatest private library in England and now offered an unparalleled collection of teaching materials to Henry’s circle.

The king confirmed Adam Newton in his post as Henry’s principal tutor, and Walter Quin to assist. Newton prevailed on the prince to ask the king to give the vacant, lucrative post of the deanery of Durham to him. (Newton was establishing himself at court by marrying into the Puckerings, an important Elizabethan political family.) Henry did so, writing to his father, the prince said, not because I think ‘your Majesty is unmindful of the promise he made at Hampton Court’ that the Dean’s position would go to Newton in due time, but because I want to ‘show the desire I have to do good to my master’. Henry’s bookish father wanted his son to esteem his tutor. Henry’s letter jogged his father’s memory. Newton got the post of Dean of Durham.

In his domestic sphere, David Foulis retained his place as cofferer in charge of Henry’s wardrobe. David Murray became the prince’s Gentleman of the Purse, and remained in the bedchamber as Groom of the Stool. The affectionate, constant presence of men such as Newton, Foulis and Murray helped give Henry’s new life in England stability. His parents came and went, but these men abided continuously, and seemed to love and honour each other.

They bickered like a family too. Newton and Murray ‘did give [the prince] liberty of jesting pleasantly with’ them, initiating banter. Playing shuffleboard, Newton saw Henry swapping his coins to see if a different one gave him an edge. He told Henry he ‘did ill to change them so oft’. Taking a coin in hand, he told Henry to watch. Newton would ‘play well enough without changing’. He shoved his penny – and lost.

‘Well thrown master,’ Henry crowed.

Newton pushed himself back from the table. He ‘would not strive with a Prince at shuffleboard’, he said.

‘You Gown men,’ Henry countered, ‘should be best at such exercises, being not meet for those that are more stirring’ – such as archery, or artillery practice, or preparing to lead men into war.

‘Yes,’ Newton said, ‘I am. Fit for whipping of boys.’

‘You need not vaunt of that which a ploughman … can do better than you,’ Henry laughed.

‘Yet can I do more,’ Newton eyed him. ‘I can govern foolish children.’

Henry looked up ‘smiling’, and acknowledged that a man ‘had need be a wise man that would do that’.

The king and Privy Council extended Henry’s ‘Scottish family’ to reflect the prince’s enlarged British identity. James appointed an Englishman, Sir Thomas Chaloner, to replace the Earl of Mar and run Henry’s household. Determined to maintain her connection with Henry, the queen gave Nonsuch and all her private estates over to Chaloner’s management. As governor, after the king and council, Chaloner had the last word on who came and went and lived at Nonsuch. Before 1603, Cecil had trusted him to carry Elizabeth’s pension to James in Scotland, and Cecil’s own secret correspondence about the succession. Awarding Chaloner this high office, the king expressed his confidence in him, rewarding Sir Thomas for those long, perilous journeys.

Chaloner had grown up with Cecil at the intellectual, godly college set up by Cecil’s father, the great statesman Lord Burghley. Cecil knew what a great house should look like, and how it should run. Chaloner shared the contemporary obsession with alchemy and chemistry; he maintained a good friendship with the magus John Dee, and corresponded with the Dutch inventor, Cornelius Drebbel, encouraging him to come to England and have Henry patronise him. Chaloner’s scientific endeavours would lead to the discovery of alum on his estate in Yorkshire. He obtained a licence to exploit the mineral, which was widely used in shaving, to treat sores and halitosis, to make glues, and in the purification of water.

Chaloner married Elizabeth, daughter of the late William Fleetwood, Queen Elizabeth’s Recorder of London. Chaloner’s father-in-law had been a Puritan-inclined MP. A committed royalist, Fleetwood nevertheless upheld the place of Parliament against Crown encroachments on its powers, citing Magna Carta to prove his case. Like his Fleetwood in-laws, Chaloner inclined to a more godly Protestantism than James would have liked. He understood the chance fortune had just handed the Chaloners, to build up a base among those jockeying for a place around the heir. He persuaded the king and Cecil to appoint his brother-in-law, Thomas Fleetwood, into Henry’s service as the prince’s solicitor. He encouraged Henry’s cofferer, David Foulis to marry Cordelia, another Fleetwood daughter.

Before he entered royal service, Chaloner had fought in France under Leicester, the ‘Captain-General of the Puritans’. He had tutored Leicester’s illegitimate son, Robert Dudley, and worked as an agent in France and Italy for the 2nd Earl of Essex. Chaloner brought all this experience to his new job.

Something about the prince’s first British entourage recalled the heyday of Elizabethan Protestant internationalism in the 1580s and ’90s, under Leicester, Sidney and Essex, with the group’s ‘militarised ideal of active citizenship … which emphasised the rewards of honour through virtuous service’ to the monarch and commonwealth. It seemed that Henry would soon be drinking in the heady brew of an honour cult of old blood, ceremony and magnificence, blended with humanism, Puritan-leaning religious and political values, and a pronounced martial bent. This was always likely given the character of Henry’s Scottish household, and the Scots who had accompanied him to England.

Time would tell. In the first instance though, Nonsuch was a boys’ home. The prince needed a clutch of new friends to grow up with, the best advancing him to help him rule in God’s good time. On his way south from Scotland, James had embraced Robert Devereux, son of the executed Essex, greeting him as ‘the eternal companion of our son’, and restoring the Essex title to him. The young earl had carried James’s sword during the official entry to London and was now sent to live with Henry. The king confirmed Cecil’s son, William Cecil’s, place here. Newton’s new young brother-in-law, Thomas Puckering, also gained admission.

Two of Chaloner’s five boys, William and Edward, stayed. Two other Chaloners, Thomas and James, came and went continually, joining in the hunts, martial exercises, the equestrian training and dancing. Lord Treasurer Dorset’s grandson, Thomas Glenham, came with Dorset’s nephew, Edward Sackville, arriving shortly after. Thomas Wenman appeared with his luggage trunks and tutor (Wenman’s uncle, Sir George Fermor, a veteran of Cádiz 1596, had hosted the king a few months earlier at Easton Neston). The aristocratic and the more favoured boys were educated with Henry. Others became retainers, halfway between servant and friend.

Queen Anne managed to insert into the prince’s household the relatives of her favourite ladies-in-waiting, Lucy Bedford and Penelope Rich. Lady Rich was the 3rd Earl of Essex’s aunt. Lucy Bedford’s brother, John Harington, son of Princess Elizabeth’s guardians, was sent to Henry. Against the king’s wishes, the queen appointed the nephew and heir of the late Earl of Leicester, Sir Robert Sidney, to be her Lord High Chamberlain and Surveyor General. Robert Sidney’s late brother was the poet and Puritan soldier, Sir Philip Sidney. Robert Sidney’s son came to live with Henry. Sidney and young Essex were cousins by marriage. (The 2nd Earl of Essex had married Philip Sidney’s widow.) Though Henry’s new family contained many different surnames, a dense mesh of blood, religion, and politics connected them beneath the skin.

Through these boys, Anne acquired a constant stream of news and contact with her son when she desired it. Since Henry’s household communicated continually with the king, Anne could also tap into the real heart of power: her husband’s court at Whitehall. Henry went ‘often to visit’ his mother, to ‘show his humble and loving duty towards Her Majesty’. Sometimes the queen might be busy and not admit him: he would wait ‘a long time, in vain’, before returning disappointed to his palace.

At other times, mother and son spent weeks at a time in each other’s company. In the summer of 1605, Anne and Henry stopped at Oxford on a summer progress in order to meet with the king and enrol Henry at Magdalen College. Anne and Henry watched plays and listened to music together. At the university Henry attended debates on a bewildering range of subjects, including: ‘Whether saints and angels know the thoughts of the heart’; and the political problem of ‘Whether a stranger and enemy, being detained in a hostile port by adverse winds, contrary to what had been before stipulated in a truce, may be justly killed by the inhabitants of that place’. Students and academics debated ‘Whether gold can be made by art?’ – touching on the alchemical question. Another day, the psychologically curious issue of ‘whether the imagination can produce real effects’ was discussed in its relationship to mind over matter, fantasies, and questions about the real power of magic, charms, spells, and dreams.

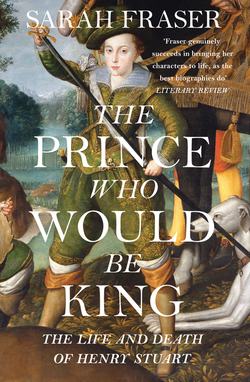

In the early days of Henry’s new life in England, a painting appeared that captured its general ambience. It is a hunting picture. Henry stands centre canvas, a friend kneels by him, with the prince caught in the act of drawing his sword from his scabbard. A stag lies by Henry’s feet, neck exposed for the crisis of the kill. The artist, Robert Peake, made two versions. It was the first ever painting to give a glimpse of a royal in action. In one version, John Harington looks up at Henry. In the other, it is young Essex. The king was devoted to the hunt, so he would have liked the ostensible subject. Yet, the boys’ clothes are the green-and-white livery colours of the Tudors, not the red-and-white of the Stuarts. In the centre of the painting, Henry’s St George Garter badge dangles at his chest, capturing the prince as a Protestant knight, prepared to kill for his cause. By contrast, his father’s portraits showed a regal, peaceful sovereign. James never liked to be immortalised in arms.

Many of Henry’s new friends arrived with their own private tutors. Dr Gurrey accompanied Essex; James Cleland, Scotsman and friend of Adam Newton, taught John Harington; Mr Bird tutored young Sidney, until Sidney stabbed his tutor, and both had to leave – the boy’s father apologising profusely to the king and queen. Thomas Wenman’s tutor was the poet William Basse. Huguenot immigrant, friend of Ben Jonson and Francis Beaumont, Basse collaborated with Shakespeare. They came across each other during their attendance on prince and king, as well as in the greater world outside palace walls.

In the schoolroom, Chaloner employed Peter Bales to give Henry a neat hand. Bales taught Henry for nearly two years before he dared petition Cecil for remuneration. A former Essexian, his unpaid service worked his passage back into favour. The Earl of Rutland introduced Robert Dallington as another unpaid tutor, who might be given a wage if he made himself useful for long enough. A brilliant scholar, Dallington had been imprisoned by Elizabeth I, along with Rutland and Bales, in 1601 when they rose with Essex. These floating tutors, along with various senior aristocrats, would be able to educate Henry’s whole person about his role and his history.

From the other side of the religious divide, the crypto-Catholic Howards, led by the earls of Suffolk and Northampton, generated a connection to Nonsuch through boys like Rowland Cotton, now admitted to serve Henry. Rowland’s father, Sir Robert Cotton, MP and the most eminent antiquary in England, was Northampton’s friend and client.

The other high-placed Howard, Lord High Admiral Nottingham, had no children to place around Henry. Instead he commissioned a model ship, twenty-five feet long, as a gift. He told shipwright Phineas Pett to sail it up to Limehouse and anchor it ‘right against the King’s lodgings’. After lunch on Thursday, 22 March 1604, Nottingham led Henry and his friends on board. Pett ordered the little ship to weigh anchor, ‘under both topsails and foresail’, and they sailed downriver as far as St Paul’s Wharf.

It was love at first sight. The speed and power of a ship moving under him, and the freedom out on the water, thrilled Henry. He took a great silver bowl of wine in his hands, named his first ship the Disdain (how fighting men and ships reacted to danger) and drank to her. All his young friends drank after him. Then Henry walked over to the side of the vessel, leaned out and poured the rest of the wine into the Thames as a libation, tossing the bowl in after it.

Northampton lavished flattery on Henry, as he did the king. The prince was a Renaissance prodigy, he said, matching ‘Mercury with Diana … study with exercise’.