Читать книгу Harry and Hope - Sarah Lean, Sarah Lean - Страница 7

Оглавление

It must have snowed on the mountain in the night.

“Have you seen it yet, Frank?” I shouted downstairs.

“You mean did I hear?”

“I know, funny, isn’t it? The snow’s so quiet but it’s making all the animals noisy.”

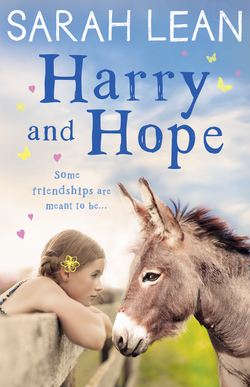

We didn’t normally see snow on Canigou in May, and it made the village dogs bark in that crazy way dogs do when something is out of place. Harry, Frank’s donkey, was down in his shed, chin up on the half open door, calling like a creaky violin.

Frank came up to the roof terrace where I’d been sleeping in the hammock. He leaned over the red tiles next to me and we looked at Canigou, sparkling at the top like a jewellery shop.

And it’s the kind of thing that is hard to describe, when snow is what you can see while the sun is warming your skin. How did it feel? To see one thing and feel the complete opposite? I only knew that other things didn’t seem to fit together properly at the moment either; that my mother and Frank seemed as far apart as the snow and the sun.

“Frank, at school Madame was telling us that the things we do affect the environment, you know, like leaving lights on, things like that,” I said. “Well, I left the lights on in the girls’ loo.”

Frank smiled. Frank was my mother’s boyfriend, but that won’t tell you what he meant to me at all. He’d lived in our guesthouse next door for three years and he wouldn’t ever say the things to me that Madame had said when I forgot to turn the lights off. In fact, what he did was leave a soft friendly silence, so I knew I could ask what I wanted to ask, because I wasn’t sure about the whole environment thing.

“Did I make it snow on Canigou?”

“Leave the light on and see if it snows again,” he whispered, grinning.

He made the world seem real simple, like a little light switch right under my fingertips. But there were other complicated things.

“Remember when the cherry blossom fell a few weeks ago?” I said.

He nodded.

“How many people do you think have seen pink snow?”

“Only people who see the world like you.”

“And you.”

I looked out from all four corners of the terrace.

South was the meadow, and then the Massimos’ vineyards that belonged to my best friend Peter’s family – lines and lines of vines curving over the steep mountainside, making long lazy shadows across the red soil paths. I thought of the vines with their new green leaves twirling along the gnarly arms, reaching out to curl around each other, like they needed to know they weren’t alone; that they’d be strong enough together to grow their grapes.

North were the gigantic plane trees with big roots and trunks that cracked the roads and pavements around the village.

East was the village, the roofs of the houses stacked on the mountainside like giant orangey coloured books left open and abandoned halfway through a story.

West were the cherry fields, and Canigou, the highest peak that we could see in the French Pyrenees. It soared over the village and the vineyards, high above us.

I touched the things I kept in the curve of the roof tiles, the wooden things Frank had carved for me. I whispered their names and picked them up, familiar, warm and softly smooth in my hands: humming bird, the letter H, mermaid, donkey, cherries, and the latest one – the olive tree knot made into a walking-stick handle that Frank said I might need to lean on to go around the vineyards with Peter when we’re ninety-nine. Always in that order. The order that Frank made them.

“What you thinking about, Frank?”

“The world,” he said quietly. “And cherry blossom.”

When you’re twelve, it takes a long time for the different sounds and words you’ve heard and the things you’ve seen to end up some place deep inside of you where you can make sense of them. It was that morning when I worked out what my feelings had been trying to tell me; when I saw Frank looking at our mountain like he was remembering something he missed; when I saw the passport sticking out of his pocket.

It felt like even the crazy dogs had known before me, as if even the mountain had been listening and watching and trying to tell me.

Frank looked over.

“Spill,” he said, which is what he always said when he knew there were words swirling inside me that I couldn’t seem to get out.

“Why did you travel all around the world, Frank? I mean, you went to loads of different countries for twenty years before you came here, and that’s, like, a really, really long time to be travelling.”

“Something in me,” he said.

“But you don’t need to go travelling again, do you?”

For three whole years my mother and I had been more than the rest of the world to him.

He looked down at his pocket, knew what I had seen. Tilted his leather hat forward to shade his eyes.

“What I mean is…” I didn’t know exactly how to explain. A boyfriend was somebody for my mother. For me, it used to be a person who picked me up and swirled me around and bought me soft toys which, after a while, I binned because the person who bought them always left. But that wasn’t what Frank did. There wasn’t a word for what Frank was to me. I mean, how can you explain something when there isn’t even a word for it? I just wanted to ask: if he was thinking about leaving, what about me? How would we still fit together?

“What I mean is…” I tried again. “Say you like cherries, which I do, and then you eat them with almonds, which I also like a lot… you get something else, right? Something that makes the cherries more cherry-ish and the almonds more kind of almond-y.”

“Like tomatoes and basil?” Frank said. His favourite.

Down below us, Harry kicked at his door. And Harry… well, you couldn’t have Frank without Harry. They were definitely as good together as yoghurt and honey.

“Yes, like that,” I said. “But also you and Harry, Mum and you, you know, there’s these kinds of pairs of us.”

“You and Peter?”

“Yeah, us too. These pairs you made of us.” I picked the little wooden donkey up, turned it in my hands. “I feel kind of smoother, and sort of… more, when we’re together.” That’s what I felt about me and Frank. “I’m kind of more me when you’re around.”

“Hope Malone,” he said. “You have your own things that are just you.”

I said, “But I’d be just half of me without you.”

Frank pushed his passport deeper into his pocket.

“Are you planning on going somewhere, Frank?”

“We’ll talk later,” he said as Harry’s hoof clattered against his shed again. “I’d better let that donkey out before he kicks the door down.”