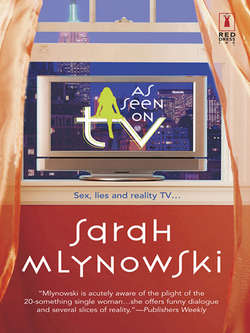

Читать книгу As Seen On Tv - Sarah Mlynowski - Страница 12

3 Wonder Woman

ОглавлениеShould you be concerned if your boyfriend lies about you?

We’re lying on the grass at Union Square Park. My head is on his stomach and every time I move, I scrape my ear against his belt buckle. I shift so that the ants don’t crawl up my skirt while Steve tells me about when he was a junior in college and his mother found a crushed cigarette in his jean pocket.

“Why was your mother still doing your laundry?” I ask. “You were twenty-one, right?”

“Not everyone has her own house when she’s sixteen.”

A cloud covers the sun and the sky looks like one of its lightbulbs has burst. “My father flew in once a month for a weekend,” I answer.

“If I were your father, I never would have let you live by yourself,” he says, puffing up his chest.

“He asked me to come with him. I said no.” Even though I am looking down at Steve’s feet, I can tell that he is shaking his head. Is he wearing two different socks? Yes, he is wearing two different socks.

“I wouldn’t have given you a choice. There’s no way I’d leave my sixteen-year-old daughter by herself. Especially after what you’ve been through.”

He says “been through” with dread and awe, like a nine-year-old girl asking her older sister what getting her period feels like. Dana called it the Double D effect. Divorce and Death. “First that, and now this,” mothers of friends would whisper, not wanting to look us in the eye for fear the bad luck would spread through the room like cancer. Snapping the shoulder straps of our bras would be our secret signal, our “they’re feeling sorry for us” or “they don’t know what we know” sign.

Sometimes Dana makes fun of these people, behind their backs or to their faces. “It must be so hard for your father,” one of her co-counselors said, a co-counselor who was new to camp. Dana couldn’t stand her, thought she was an airhead. “Not so hard,” Dana replied. “He left her three years before she died, and he’d been fooling around since the day he married her. At least he doesn’t have to pay alimony anymore.”

When my friend Millie’s parents separated in high school and she lost ten pounds from “not being hungry,” I tried to patiently coax her to have a slice of pizza, to get over it, but eventually I snapped. “For God’s sake, at least they’re not dead,” I yelled at her and then felt cruel and horrible and spent the next week apologizing.

Any kind of loss is painful. But after your mother dies, divorce seems like a sprained wrist, compared to an amputated hand.

Dana and I divide people into those who know what we know and those who don’t. A secret club with loss as our badge.

Steve doesn’t know. He looks into the murky and bottomless future and sees something sparkling and blue. I love it that he doesn’t know, but constantly worry about the day he will. Sooner or later everyone does.

His grandmother died last June. It was sad for him, she was his last remaining grandparent, but it didn’t exactly rock his world. He still laughed at the Letterman’s Top Ten list that night.

I think the funeral was harder for me than it was for him. I hate funerals. I don’t breathe well and the walls start to contract.

I met his grandmother a few times before she died. Steve brought me to see her whenever he came to visit me. We sat politely with her at her retirement home while she fed us stale chocolate and tea. She liked me right away, I don’t know why, but she kept grabbing on tight to my wrist. “I want to dance at your wedding,” she said and we blushed. “You have to do it soon, I don’t have that much time,” she’d say.

We’d wave her comment away (“don’t be silly, you have lots of time”) but what are you supposed to say to an eighty-seven-year-old?

“You can have this,” she said and pointed to the engagement ring she still wore. It was beautiful, platinum band, a large round diamond, two baguettes. We kept blushing and she kept insisting.

I wonder what happened to the ring.

Back to my validation.

“Dana was doing her master’s, the first one, so she was only an hour away from my dad’s house,” I say. “She made the drive at least once a week to keep an eye out for me.” Dana had reveled in the pop-by—she’d claim to be drowning at the library and then sneak into the house to make sure tattooed men and acid tablets weren’t decorating the furniture.

My dad had invited me to move with him to New York. What was he supposed to do, not take the promotion? I told him there was no chance I was going. No way. Have a good time. Enjoy. I’d visit. Tobias, the guy I had been in love with since the first day of my freshman year in high school had finally realized what I had been telepathically telling him for twelve months—that we were meant to hold hands and laugh and sneak kisses between classes. There was no way, no way, I was moving now that we were finally a couple.

The idea of senior year, of trips to the shopping center’s food court where we’d hog tables and not buy anything, of destination-less drives of where-should-we-go-I-don’t-know-where-do-you-want-to-go taking place in my absence made me feel claustrophobic and abandoned, as if I’d been waiting in the back of the storage cupboard between the winter coats, not knowing that hide-and-seek was long over.

I told my dad that after all I’d “been through” it would be too traumatizing to have to leave behind the final memories of my mother.

When I was eleven at summer camp, I found out a boy I liked didn’t want to go to the social with me. Humiliated, I locked myself in the wooden bathroom stall at the back of my cabin and sobbed and sobbed until Carrie, my father’s now girlfriend, and my then-counselor, knocked on the door and begged me to tell her what was wrong. I told her I missed my mother.

Unlike Carrie, my father should have known that excuse was full of crap.

Before my parents separated, we all lived in Fort Lauderdale. When I was three, my mother started receiving a plethora of silent, heavy-breathing phone calls (Dana was ten so she remembers these things), which led to the discovery that my father was sleeping with his secretary. Very original, Dad. Anyway, when confronted, instead of begging for forgiveness, buying jewelry and taking large amounts of Depo-Provera, or whatever today’s chemical castration drug of choice is, my father decided that marriage, like last winter’s coat, no longer suited him. We stayed in the house we had grown up in and my dad bought a condo in Palm Beach. When we’d visit for a weekend, we’d transform the living room couch into our bed (“Sunny, doll, be careful with Daddy’s things please.”). “Fa-ther,” Dana would say, she always said his name like that, in two syllables, until she was older and started referring to him as The Jackass, “we’re here for two days, do you think you could make a little room for us?”

“It’s okay,” I’d say quickly hoping to placate them both.

Once every few months he would take us to Walt Disney World. “Sunny,” he’d say. “Do you want to go on ‘It’s a Small World’ again?” He tended to address questions to me, or to “You Kids” instead of directly to Dana. She was always watching him with her best Andy Rooney I-Know-What-You’re-Up-To look, full of mistrust and loathing. I’d walk between them holding their hands, trying to bridge the gap.

When I was six and my mother died, my dad bought a bigger house in Palm Beach. We got our own rooms. Mine was upstairs and Dana’s was in the basement.

My father viewed us as goldfish. Feed three times a day, or at least make sure housekeeper prepares meals. Drop three hundred dollars into jacket pockets weekly to cover transportation, entertainment and clothing costs. Occasionally, press face against glass bowl to make sure children are still swimming.

As a strategy consultant he spent most weekdays in other cities and most weekends in the company of various women we were only occasionally allowed to meet. Growing up we had various housekeepers/baby-sitters who lived with us until Dana was eighteen and I was twelve. After that they came Monday to Friday during the day only. Dana decided to stay in Palm Beach with me for college instead of going away to school, so I was never on my own. She only moved out when she was twenty-two and got into her first master’s program in Miami.

When she told me the news, we were eating chicken wings from our favorite Florida restaurant chain, Clucks, while lying on the white couch. I knew we wouldn’t drop anything, we’d been eating like this since we’d moved in whenever no one was around to tell us not to.

“Forget it, I won’t go,” she said.

“Yes, you will,” I told her. “It’s an hour away. I’ll be fine. It’s not like I’m living alone—I live with my father. I’ll only be alone for a few nights at a time, tops.”

Two months later, he took the job in New York.

When I went to visit Dana in Miami for the day, and told her that our father was moving, she was furious. “That Jackass wants to play bachelor in the city. What kind of a father leaves a sixteen-year-old to live in a house by herself?” I begged her not to complain, not to ruin it. I was mature, I could do it.

“Sunny,” Steve says, mercifully interrupting my train of thought. I love listening to him say my name.

I roll over so I can see his beautiful face. “Yes, Steven?”

“I have to tell you something.” He sounds so serious, like a college recruiter asking me about my plans for the future.

Uh-oh. He’s changed his mind. Now? He changed his mind now? A week after he asks me to move in? Why did he change his mind? Bastard.

Maybe it’s worse. You don’t say, “I have to tell you something,” unless you’re unleashing appalling news. He cheated on me. He’s already married. He’s a woman.

“I…” He plucks a blade of grass from the ground instead of continuing.

Hello? I prefer the quick-motion Band-Aid removal rather than the taunting millimeter-by-cruel-millimeter torture. “Yeeeees?” I say, attempting to stretch the word into a multisyllable confession prompter.

“You’re so going to think I’m lame when I tell you this.”

He’s getting lamer by the second by not coming out with it already. “I won’t.”

“It’s just that…” His voice trails off again.

“What? I will not get mad, I promise, just tell me.” You have to act like you won’t get mad, otherwise they’ll never tell.

He sighs. “I can’t put your name on the answering machine. I don’t want to tell my parents that we live together. They’ll freak out.”

Is that all? I almost laugh out loud. Why should I care what he tells or doesn’t tell his parents? I put on my best I’m-the-most-even-tempered-girlfriend-in-the-universe smile. “Tell your parents whatever you want,” I say, my voice full of peppered reassurance.

“Really?” he asks, and his chest droops back to its deflated state. “I thought you’d be insulted.”

Insulted? Why would I be insulted? Unless what he said was intended to be a snub. Was it a snub? Was he cunningly letting me know that his parents don’t approve of me and will never accept me in their family? Because my mom converted to Judaism and wasn’t born Jewish? Am I not good enough? I met them a few times and they smiled and joked with me and invited us for dinner every time Steve was in town. The first few times he stayed with them, but eventually he told them he was staying at my place. Is Steve embarrassed of me? Is he never planning on telling them? Ever? Is he keeping me in the closet? I storm into a sitting position, jutting his stomach with my elbow. “Are you going to lie to your friends, too? Am I some dirty little secret that you think will parade around the bedroom in slinky lingerie but whom you’ll never take out in public?” Who does this guy think he is?

He turns the color of smoked salmon. “Of course, my friends know you’re moving in. What kind of person do you think I am? I’ve never been more excited about anything in my life. It’s just that you know my parents are religious. My mom would freak out if she knew we were living together without being married. It’s not like I’ll have to hide any of your stuff ever, they live in Miami. It’s not forever.”

“What do you mean it’s not forever?” I turn to glare at him. “So you think I move in with all the guys I date? That we’re living together until you find something better?”

He wraps his arms around my shoulders, pulls me back to his stomach and pinches my nose with his fingers. Normally, when he pinches, he says, “Honk,” which is one of his favorite and most embarrassing games to play in public places. “What I meant, Psycho, is that eventually we’ll get engaged.”

Oops. “I see,” I say, for lack of coming up with anything more clever.

“If it bothers you, I’ll tell them. Be truthful. Do you care?”

How can I be mad at him after an “eventually we’ll get engaged” comment? Is he planning on proposing? How long are we supposed to live together before we get engaged? Are we pre-engaged? Do his parents not approve of me? “I don’t care. Honest.”

Eden’s is loud, busy and green. The walls are covered in leaves. Pots of sunflowers stem up beside various tables. The waitresses are wearing skirts made of petals and sunflower-patterned bikini tops. My dad and Carrie are waiting at the bar. I can’t believe he made it. Hah! I told Dana he’d show.

As I approach, Carrie waves her Fendi bag at me with one hand and a martini glass with the other. I know it’s a Fendi bag because it has the FF logo trampled all over it, as if one medium-sized FF isn’t obnoxious enough.

My father’s arm is wrapped around her tanned, bare shoulders. “Hi,” I say, approaching them.

“Sunny!” she shrieks, and covers her mouth with both her hands. “Look at you! You are so gorgeous. Look how gorgeous you are! You got so big!”

She hasn’t seen me since I was twelve and she was my counselor, so I won’t be insulted. “Thanks,” I say. “I think.”

“Last time I saw you, you had braces and hair down to your waist! Adam, isn’t she gorgeous?” She waves her hands at the word gorgeous as if she’s Moses thanking God for the Ten Commandments.

My father nods. “Gorgeous, doll, gorgeous.” Am I the doll or is Carrie the doll? I haven’t seen him in about six months, since I met him for dinner at China Grill on South Beach when he was in Miami meeting a client. He only had the night free because he was meeting “a friend” in the Keys. It’s strange that I hadn’t seen him in so long, considering that lately I’d been coming to New York every few weeks. The last few times I was here, he wasn’t, which was fine with me, because it’s not like I came to NewYork to see him.

“Stop making excuses for The Jackass,” Dana says inside my head.

Two months ago he was supposed to meet Steve and me at Manna, but he didn’t show. “You surprised?” Dana asked later.

My sister hasn’t spoken to my father in three years. “He’s like tobacco,” my sister once told me. “Toxic. You’ll feel better about yourself if you cut him out of your life.”

Dana sees us as two orphans against the world. She’s either been reading too much Dave Eggers or watching too many reruns of Party of Five.

Tomorrow, I’ll definitely call.

You know how when you see someone daily, you don’t notice him getting older, but when you don’t see him for a few months, you’re shocked by the change? Like when you pick up People once a year and see a picture of Harrison Ford and you can’t believe how gray Han Solo got? Well, that doesn’t happen with my father. His looks never seem to change—he’s six feet, wide-shouldered, with a full head of chocolate-brown hair, wide blue eyes framed by dark spidery lashes, and a Tom Cruise smile that takes up half his face. Whenever he decided to show up on Parents’ Day at camp, all the female counselors would flock to him as if he were a free chocolate sampler at the supermarket. “Oh, Mr. Langstein. How are you? It’s wonderful to see you, Mr. Langstein.”

“Call me Adam,” he’d say, resting his hands on their seventeen-year-old shoulders.

I guess that’s when he first noticed Carrie.

My ex-counselor continues to review my outfit. “I love that dress. Did you get it here?”

I’m wearing Dana’s white V-neck cashmere sweater dress, one of the many items she bought but still had the tag attached when she handed it down to me. “Get good use of it, it’s Nicole Miller and cost three hundred dollars,” she told me. As if that would impress me. Tell me something, can anyone tell the difference between a three-hundred-dollar dress and a thirty-dollar dress? And would anyone who could tell the difference think less of me if I were wearing the thirty-dollar dress instead of the three-hundred-dollar dress? And if anyone would think less of me, is she really the type of person whose opinion of me matters?

The dress is really soft. I thought my dad would like it. It’s so girly.

“And your hair looks gorgeous.” All right, she’s made her point. I put it back in a low bun, because my father has always nagged me to “pull your hair back and show off that pretty face. Why are you hiding it with all that hair?”

Okay, Carrie, that’s enough sucking up for today. The occasional batting-eyed hopefuls I was allowed to meet have always held the mistaken idea that a nod from Dana or me would high-speed them from “we hang out on Saturday nights” to “look at the Harry Winston rock on my finger” status. As a teenager I was bombarded with tickets to see Michael Jackson (“Let’s do the moonwalk together, Sunny!”), Cabbage Patch Kid dolls (“Let’s change her diaper! Maybe one day we’ll have a real baby to change!”) and subscriptions to Teen Beat (“Isn’t your father as handsome as Tom Cruise, and by the way, do other women come over to the house, Sunny?”).

Sometimes I actually liked these women. Of course, as soon as my father moved on, I was expected to move on, too.

On my twelfth birthday, one of his ex-girlfriends sent me a card, wishing me a good year and telling me to call her if I ever needed anything.

“Throw that out,” my father said. “She’s only using you to get to me. Besides, it’s not appropriate for you to still see her socially.”

I threw it out.

Carrie always looked very—Vogue. Now her hair has that three-hundred-dollar blond highlighted, blow-dried straight then attacked with a curling iron look. She’s wearing black boot-cut pants, a tight silver strapless shirt and a black cashmere pashmina draped behind her back and over her arms. She looks shorter than she used to, despite her three-inch stiletto boots—ouch—but I think that’s because the last time I saw her I was only four feet tall. Now she looks about my height, five foot six. My brown patent leather pumps only add an inch. I don’t normally wear shoes like these out, they’re my suit shoes, my interview shoes. According to Dana, they’re called Mary Janes, meaning they’re pumps with a strap. They’re the only shoes I have that match with this dress. I’m not a fashion connoisseur, but I didn’t think my sneakers would go.

The hostess shows us to our table while batting her eyes, swooshing her petal skirt and thrusting her sunflower bikinied breasts at my dad. Carrie notices and wraps her fingers around his wrist like a jaywalking mother clinging to her daughter. Thankfully the waiter in our section is male. For some reason only the female staff members are dressed in garden-appropriate costumes. Maybe no one wants waiters clothed in fig leaves handling their shrimps. Carrie and my dad claim the seats in the corner, facing outward, and I slide into the art deco highly uncomfortable metal chair across from my father and an ivy-covered wall.

Carrie passes me her drink. “Their apple martinis are to die for,” she says. “Try mine.”

I take a careful sip, not wanting to touch her red lipstick marks. “Pretty good.”

“Do you want one?” my dad asks me. He looks at Carrie. “You want another one, doll?” That answers my previous unanswered question. She’s Doll tonight.

Alcohol will surely increase this evening’s enjoyment factor. “Why not?” I answer before Doll has a chance to speak.

Carrie raises her hand and waves over our waiter. “She would like an apple martini, please. Can I have another one, too? Thanks.”

We order appetizers and the main course after listening to Carrie’s endorsements. (“The crab cakes are heavenly, trust me. Do you like ostrich? It’s fabulous here. Try it. The shrimps in black bean sauce are also to die for.”) Eating ostrich sounds mildly grotesque, so I decide on the shrimp. Once we’ve ordered, my dad asks me about my job search.

“I have interviews set up all day on Monday,” I say. “Hopefully some sort of job offer will come out of it.”

“All you need is one, right?” Carrie asks. “Just like a man.” She smiles at my dad. I want to tell her she shouldn’t get her hopes up.

I wonder what she does for a living. What’s the etiquette for asking? People always strike me as crass when they inquire about my work. It’s as if they’re trying to sneak a peek at my paycheck. And what if she doesn’t work? She might be one of those Manhattan socialites. Maybe she’s never set a pedicured toe into a job since summer camp.

Oh, hell. “So what do you do, Carrie?”

She finishes the rest of the martini and swishes it around her mouth like mouthwash. “I’m an associate at Character Casting. It’s a talent agency.”

“Cool. You find actors for movies and commercials?”

“Basically. Lately we’ve been doing a lot of reality TV.”

“I thought reality TV used real people.”

“They do use real people,” she declares. “The reality shows all have open casting, but they also rely on agencies to find people with unique abilities and diverse backgrounds. We cast most of the singles for DreamDates. Have you ever seen it?”

“You watch those reality TV shows?” my father asks me.

“Not really,” I say. “I’m not a huge TV watcher. I watch the news, and Letterman. I used to watch a ton of TV when I was in high school.”

When I lived on my own, there wasn’t much else to do when all my friends were having dinner with their families.

“Honestly, I haven’t gotten into the reality TV trend thing. I watched a DreamDates episode once, and it was kind of funny.” If you consider witnessing someone else’s complete humiliation funny. Ex-boyfriends were there, background music was blasting, people were crying. I was surprised when I read an article reporting the show was incredibly popular.

“They’re everywhere,” Carrie whispers, leaning in like a conspirator. “The networks are premiering dozens more this season. They love them—they don’t have to pay the writers or the actors. Even stodgy cable networks like TRS are launching them. These days it’s the only surefire way to get into the eighteen-to thirty-four market. In the past year we’ve casted for Freshman Year, The Model’s Life, Party Girls, and get this one—Call Girls. Yup. It’s a reality show about a Vegas whorehouse. Unreal, huh?”

I shake my head, incredulous. Don’t individuals have enough problems without wanting to burden themselves with other people’s exaggerated ones? “How did you cast for that? Answer the Village Voice ads?”

“You don’t want to know.” Our drinks and appetizers arrive and Carrie continues between bites of crab cake. “We’re swamped these days. You know what—if none of your interviews work out, we could definitely use a temp at Character.” She looks over at my father, as though seeking approval in the form of a nod or pat on the knee.

My dad says, “That’s a great idea.”

If Carrie were a Labrador, her tail would wag.

Flipping through pictures of anorexic wanna-be actresses all day? Thanks, but no thanks.

A tall brown-haired man wearing a Hawaiian-patterned shirt, black pants, shiny leather loafers, a square goatee and tiny John Lennon glasses approaches our table and lays his hands palms down on our table. “Carrie! What’s up?” he says, his glance glossing over my father and me.

Carrie straightens up in her chair. “Howard, hello. You know my boyfriend, Adam.” He shakes my dad’s hand. “And this is his daughter, Sunny. Sunny, Howard Brown.”

“It’s a pleasure,” he says to me. I lift my hand to shake his, and he kisses the back of it. His lips feel oily and he reminds me of a counselor I knew at Abina, Mark Ryman, who had thought he was the camp’s Danny Zukoe. He would buy the fifteen-year-old counselors-in-training shots of tequila to get them drunk enough to sit on his lap.

Carrie looks around the room. “Who are you here with?”

He rubs his hands together as if he’s trying to warm them up. “My wife. She’s getting us another table. I don’t like where they sat us.” He motions across the room at a blonde in a fur-collared white sweater.

Carrie waves but the wife doesn’t wave back. “Tell her I say hello,” Carrie says.

As soon as he walks away, Carrie hunches toward me and whispers, “That was the executive producer for the show Party Girls I was telling you about. His wife is a complete bitch. A jealous freak. She’s convinced he’s screwing half the women in New York.”

“Why?”

“Because he’s screwing half the women in New York.”

“He has the slime vibe,” I say.

“Yeah, but he’s a genius. He created the show, too. He’s even the one who sold the idea to TRS, which is miraculous, considering that the network is so conservative. Since I cast two of the girls for his show, he’s considering hiring me as a liaison. You know, to make sure they stay gorgeous and do their job.”

“So what are these brilliant producers going to do next? Tape people going to the bathroom?” my dad asks, nipping back into the conversation at the word gorgeous. Maybe Carrie should start peppering her everyday conversation with sexy adjectives. Sizzling weather. Spicy clients.

“You’re so funny, honey.” Carrie giggles a little-girl laugh.

“What does a producer do exactly?” I ask. I’ve never understood what that job title entails.

“Not much,” my father says.

“Very funny, Adam, that’s not true. They plan everything, hire everyone, manage the money, make sure everything is on schedule, premiere the show.”

Sounds like what I do, but with TV shows instead of carbonated fruit juices.

“This concept is very original. It follows four girls at different bars on Saturday nights.”

Aren’t there a million shows like that? “Very original,” I say.

Carrie nods, either missing or ignoring my sarcasm. “The camera only follows the girls on Saturday nights. The unique part is that the show airs the next night. We call it ALR taping, Almost Live Reality. An incredibly quick taping-to-broadcasting turnaround.” Her voice switches into sell-mode. I imagine her shaking hands with prospective spicy clients, nodding profusely. “No one knows what’s going to happen next week, not even Howard. Also, this show is going to be far more accurate in terms of the scene than other Real TV shows. Usually these shows are taped in their entirety, then edited, then broadcasted. But even though a club is sizzling hot during the summer, it could easily be out by winter. With ALR, Party Girls will be a lot more immediate. Much more now. Much more real.”

Much more ridiculous? How could anyone be real when she’s being stalked by a camera? I can’t even be natural taking a passport photo. “So how do you pick the girls who are on the show?” I ask.

She rolls her eyes. “You would not believe the process. Applicants had to fill out forms and send in sample tapes, then we did a round of interviews, then we finally chose four girls.” Carrie looks over at my father to make sure he’s listening, but realizes that he’s busy watching the waitresses in their garden outfits. I can tell she’s contemplating what she can say to break him out of his two-timing reverie. Doesn’t she know it’s never going to happen? “Why four?” I ask.

She seems to be searching her stock answers for an appropriate response. “Women are normally friends in groups of four.”

I laugh. “And has that happened since Sex and the City became a huge success?” I don’t have HBO, but both Millie and Dana do and they’ve made me watch enough episodes. Not my life (the Mr. Bigs, the Cosmopolitans, the Manolo Blahnik obsession), but I still laughed. Is that show even on anymore? I take another sip of my martini.

She searches for a stock answer for that, too, but appears to come up blank. She nods. “I suppose so. I need another drink,” she says, motioning to the waiter.

Two martinis later, there’s a commotion behind me.

Carrie strains her neck to see what’s going on. “Yikes, something is going down over there.” She points multiple fingers over my head. I turn to take a look.

A blond woman in a tweed Newsboy cap is standing in front of her chair, clutching her neck. A flushed man beside her is frantically trying to convince her to drink a glass of water. “Take it! Karen? Kar? Are you choking?”

I doubt the bluish tint to her face means no. She’s fine, thank you very much, and why don’t you sit down and finish your black beans and shrimp?

Apparently, Carrie was right. The dish is to die for.

Is it too late to change my order?

Silence creeps through Eden’s like frost. Karen, the choking woman, motions to her neck and throws the water on the floor. The glass splinters around her.

The man spears his eyes around the restaurant. “I need a doctor!” he yells. Our waiter howls. The hostess starts to cry.

No one stands up.

“Oh my. Oh my,” Carrie says. “She’s choking. She’s choking.” She giggles and her hands respond by waving. “Oh my. What do we do? Adam? What do we do?”

Karen heaves silently, without emitting a single sound. Is she going to pass out? Is she going to die? Are we about to witness a woman die over a plate of shrimp?

Way back when, in the days before Hotmail, DVDs and Britney Spears, to get my lifeguard certification I had to practice doing a stomach thrust. Unfortunately I’ve never actually performed this activity on anything except a mannequin.

There must be a doctor somewhere in this restaurant. I look for someone exploding into action with a stethoscope around his neck, or a prescription pad in hand. Someone must be more qualified than a has-been summer-camp lifeguard. I don’t even think my certification is still valid. I’m barely qualified to throw her a lifejacket.

I coached children on the front crawl. I blew a whistle during free swim. Once every summer we’d pretend a kid had lost his buddy and we’d hold hands, sweep the water. Since we knew the kid was hiding in the flutter-board shed reading an Archie comic, that’s not saying much for my emergency skills.

The woman is the same color as the curaçao in her martini glass. “Can’t anyone help?” the man begs.

Shit.

My head feels light and I wish I hadn’t had that second cocktail, but I jump to my feet and sprint toward the air-challenged woman. “I’m going to do the Heimlich on you, okay?” Are you supposed to ask permission? Or does that scare them? Too late.

I stand behind her, make a fist with my right hand and place it, thumb toward the woman, between her rib cage and waist. Her stomach feels squishy and hot. I put my other hand on top of the fist. Okay. So far, so good. I’m already congratulating myself and I haven’t done anything yet. All right, it’s outward and inward. No, inward and upward. That’s it. I thrust my hand inward and upward. Nothing. Inward and upward. Again. Inward and upward. Fuck. How many times am I supposed to do this? She can’t die while I’m touching her, can she? There should be some kind of rule—someone can’t die in a stranger’s arms.

A chunk of shrimp soars out of the woman’s mouth, landing in her glass and splashing blue liquid onto the white tablecloth. She coughs. She breathes. She turns around. She throws up.

The restaurant claps.

“Are you okay, Kar?” her husband/date/male friend asks her.

She inhales again and nods. I hand her the cloth napkin that was on the floor. I assume it’s hers.

Dazed, she sits down and says, “Thank you.”

You’re welcome! Everyone is looking at me, pointing. Wow. I can’t believe I just did that. Pretty impressive. I’d love to see what that looked like. Any chance anyone got that on videotape? “How do you feel?” I ask.

“Light-headed,” she says, “but all right.” A waiter hands her a glass of water and she downs it.

People are still clapping. I look at my table in the corner—Carrie is honoring me with a standing ovation, her hands gesturing all over the place. My father has his glass raised to me in a toast. A toast. My father is toasting me!

I do one of those shy I-do-what-I-can smiles. I might be a superhero. I saved a person’s life. Aren’t there customs where she’s supposed to become my slave?

The maitre d’comes over and thanks me. Maxwell the chef tells me I’m a star. Karen and her husband start to cry and tell me they can’t thank me enough. Karen then hands me her business card and a hundred-dollar bill. I decline the bill but take the business card. Why not? It says Karen Dansk, VP Programming, Women’s Network. Who knows? Maybe I can get Dana a job as a Manhattan reporter.

Ten minutes and thousands of accolades later I head back to my table. My father motions to his mouth and then to his chest.

“What?” I ask. He’s so proud he’s speechless? I’ve touched his heart? I’ve rekindled his hope in the human spirit?

“Wipe your sweater,” he says.

I look down. Dana’s three-hundred-dollar cashmere dress is covered in shrimp and black bean remnants.

I wonder if I can ask Maxwell to make me the ostrich instead.