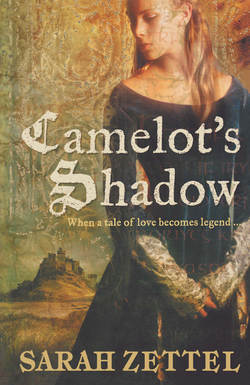

Читать книгу Camelot’s Shadow - Sarah Zettel - Страница 10

FIVE

ОглавлениеThe day was clear as crystal and at least as cold. Rhian was glad Sir Gawain kept the pace brisk, for although the wind stung her cheeks, Thetis’s motion helped keep her warm and distracted her somewhat from the lack of food.

And she needed every distraction she could get. They were still in the wooded country, with the great trees gathering close to the road, waving their branches in salute to the morning’s wind. This was not a well-travelled section of the road, and the ruts and holes had become puddles the size of young lakes. Twice they had to dismount and lead the horses through the trees to avoid burgeoning bogs. Sunlight and shadow shifted, spread and scattered like foam on the sea. The world filled with the rush and creak of the trees’ song, a constant accompaniment to the calls of birds and the hundred nameless noises of the newly wakened forest dwellers, all of them seeking shelter somewhere away from the disturbance made by three horses and two human beings. It took all Rhian’s strength to keep from starting at shadows ahead that might be a dark man with heavy-lidded eyes, or from turning constantly to see behind. Were the only hoofbeats she heard truly from the three horses of their party? Or were there others? Their tracks were plain in the mud and the soft earth along many long stretches where the stones the Romans had laid down were broken and gone. Anyone, certainly any of father’s men, would only have to look to know where they had passed. How much more would a sorcerer be able to do?

It did not help at all that the words from one dark ballad had begun to beat their time through her mind again and again and would not be shifted.

‘Light down, light down, Lady Isobel,’ said he,

‘For we are come to the place where you are to die.’

That all ended well enough for the lady in that tale gave her no comfort. Her mind could not reach that far.

For we are come to the place where you are to die.

‘I see my lady favours a bow.’

Rhian nearly jumped out of her skin. Thetis whickered and broke stride. Rhian had to pat the horse’s neck and prod her to continue before she could look up at Gawain, whose face was all casual inquiry.

‘I do, yes,’ she answered, trying to warm to the idea of polite conversation. What was that in the trees? Was it only a bird?

‘Do you hunt?’ he went on.

‘When I can.’ How many sets of hooves drummed on the road? Mud muffled and confused sound, turning steady drumming into wet and uneven plodding. The way ahead rose steeply. They were leaving the lowlands for the hills, with their dells and valleys and deep folds in the land, where anyone might conceal themselves. She could see next to nothing. She could not hear properly.

‘Lady Rhian.’

Again, Rhian jumped. Again Thetis complained of it and had to be soothed. When she was able to look up at Gawain, his fine face was all sympathy.

‘Take heart, Lady Rhian,’ he said. ‘We are alone on this road.’

Rhian dropped her gaze. ‘I know it, Sir,’ she said. ‘It’s just that…if I…if…’

At her stammering, Gawain gave a small smile and Rhian felt a blush blossom across her entire face. ‘Lady Rhian,’ he said again, as gently as he had before. ‘Last night I said you were under my protection. I will not permit any harm to come to you. If an oath is necessary to make you believe this, then I swear it.’

‘Sir, please believe that I do not doubt your word. But if my father…’

‘Your father is the king’s man and needs must obey the king’s word. Until the king himself appears, that word comes from me, and I say you are going to Camelot.’

Rhian looked away, trying not to scan the budding underbrush for movement. ‘Would ‘twer that simple.’

‘It is that simple, Lady Rhian. It is law.’

He spoke the words so plainly. Did he not understand? Churlishness rose in Rhian and would not be dismissed. Before she could guard her tongue she said, ‘You have slain dragons, my lord. The rest of us know rather less of such legendary battles.’

Sir Gawain stared at her blankly for a moment. ‘God in Heaven,’ he said at last. ‘Is that what they say of me now?’

‘Every year at the feast of Christ’s Mass.’ I’ve told it myself, she added in her mind, but decided not say so aloud.

A spasm crossed the knight’s face, as if he was not certain whether he wished to laugh or curse.

Laughter won out. ‘Well then, my lady, if you can believe I have slain dragons, it should be a matter of no moment to believe I can stand up to your father!’

Much to her surprise, an answering laugh bubbled out of Rhian. It felt surprisingly fine, like a spring morning, and Gawain’s smile had returned in truth, turning his face again to that picture of a man’s beauty she had seen so briefly before, even with the dark stubble dusting his chin.

After a moment, his face grew thoughtful again, studying hers. Rhian fixed her gaze on the rising narrow way ahead, on the shifting patterns of light and shadow from the branches waving in the spring wind. Thetis did not like uneven ground and was growing nervy, so that Rhian had to concentrate on keeping her seat and on guiding her mare, which was just as well. She needed to think of something else but Sir Gawain’s eyes studying her so closely.

‘It is good to see you smile, Lady Rhian.’

It is good to believe I will smile again, thought Rhian, but that was hardly a thing she could say to this man. She concentrated instead on keeping the reins loose in her fingers. It would not do to have Thetis betraying her moods.

Perhaps in my next flight into the wilderness I should go on foot.

Gawain was not content to let her keep her peace, however. ‘May I ask your thought?’

‘Oh, it is nothing of importance, Sir.’

At this, Gawain reined his palfrey back, bringing himself as close beside Thetis as the broken road permitted so that he could look her directly in the eyes. ‘Lady, you asked this morning that I speak plainly to you. Grant me the courtesy of doing the same for me. We are not, after all, in your father’s hall, nor my uncle’s. Out here, I am only a knight errant and you are the daughter of a liegeman. Shall we then be Gawain and Rhian, you and I?’

Rhian felt her tongue freeze to the roof of her mouth. It was too presumptuous. She was not sure she could do such a thing. Yet, at the same time, she longed to.

Mother Mary, I’m becoming a stuttering fool. ‘I will try.’

‘I can ask for nothing better.’ He was smiling again, that smile that lit and filled the world and suffocated sense and senses. Part of Rhian knew she had better take hold of those same senses, or she was in severe danger of making far worse than a fool out of herself, be this man ever so refined and politic in his manner. Part of her did not care and only wanted to see him smile again. During the few heartbeats she was basking in the light of that smile, she no longer had to be afraid of what followed her, and she felt no nightmares resting on her shoulders. She greatly yearned for that relief.

‘So, Rhian,’ he stressed her name and the smile flickered about his lips as he did so. ‘If you will not tell me your thoughts, what shall we talk about instead?’

Curiosity itched at Rhian’s mind, and she decided to dare his disapproval. ‘Can mmm…’ deeply ingrained habit made her tongue stumble. ‘…you tell me what brought you to the borders of my father’s land?’

Gawain looked at her carefully, weighing and judging some quality Rhian could not guess at, and he made his decision. ‘The Saxons plan to start the wars again,’ he said. ‘I am carrying that warning to the High King.’

His words at once dropped fear into Rhian’s heart, making it beat slow and heavy and filling her with the sharp and sudden longing for the stone walls of her father’s hall. All her life, she had heard tales of the Saxon invaders, of the raids and rapes, sackings and burnings. She had also heard, and told, how High King Arthur had broken the invading forces, sending them scurrying back to Gaul, or leaving them clinging to the eastern coasts muttering to themselves in their dark fortresses behind wicker fences.

That they would come again…that they would be here…In the light of day it was comparatively easy to shake off the immediacy of magic and sorcerers, but the spear, the knife and the torch – those were far more solid things. In an instant, the trees were once again the home of terrors, and Rhian had to swallow hard against her fears.

‘How close are they?’ the words came before she had time to worry about discretion.

‘Two days’ ride.’ Gawain looked to the distance. They had topped the rise and ahead the wood seemed to be thinning, but Rhian was no longer sure of her bearings, though Gawain seemed to be. How much time has been lost already? she could practically hear him thinking.

Rhian bit her lip. ‘Is there any way to get word to my father? He should know.’

Gawain looked genuinely shocked. ‘After what he has done to you, you would care?’

‘Does my mother deserve to suffer for what my father has done?’ snapped Rhian. ‘The men and women of our holding?’

Gawain looked quickly away. ‘Forgive me, that was an unworthy thing that I said.’ The apology was smooth and courtly, as perfect as all his other manners, but there was something more underneath it, a trace of some old wound or faded nightmare of a memory. Whatever it was, Gawain shook it quickly off. ‘It would not do to let the invaders know yet that we have word of their plans. As soon as I have taken counsel with the king, I am certain he will send out messengers to his liegemen to stand in readiness.’

But will that be soon enough? It was all Rhian could do not to look back down the twilit road again.

‘I do not seem to be succeeding in reassuring you, Lady Rhian,’ Gawain said wryly.

It was indeed lighter ahead. She should concentrate on that, see it as a sign, behave properly and forget her curiosity. ‘If I want reassurance, perhaps I should simply stop asking questions.’

‘I think that such silence would ill become you.’ Was he simply being polite once more, or did he truly mean that? His face had softened, particularly around his eyes. ‘It might make the road more smooth.’

That brought him out of reverie into philosophy. ‘And where is the glory in the smooth road?’

I wonder, Sir, if you’ve forgotten who you are speaking with. ‘I have been told glory is not for ladies.’

‘I know of at least one lady who would argue that point.’ Gawain’s eyes took on a knowing glint.

Rhian drew her shoulders back and set her face in a fussy imitation of Aeldra. ‘What lady might this be to say such an unladylike thing?’

‘The High Queen, Guinevere,’ replied Gawain matter-of-factly.

Rhian found she was not ready for that answer. She concentrated on keeping seat and hands steady while Thetis picked her careful way down the slope between the stones, gouges and damp drifts of leaves. The day had warmed and clouds of midges swarmed around Thetis’s ears. Perspiration prickled Rhian’s scalp under her veil and the lack of food was beginning to have an effect on her. She wondered if Gawain had any bread in his bags that they might stop and share. The last swallow of watered wine seemed a long time ago.

‘What is she like, Queen Guinevere?’ she asked instead, not wanting to complain or slow their progress. ‘I have never been to court.’

Gawain smiled then, and for a single heartbeat, Rhian thought he looked more like a man thinking of his lady-love than one thinking of his aunt. But as he spoke, she told herself firmly that she was most mistaken.

‘A more loyal and virtuous lady is not to be found. She is wise in her counsel both public and private, and generous to those in need. Her appearance is noble in all aspects, and her grey eyes are justly famous.’

Grey-eyed Guinevere, she

who rode at the king’s left hand

the fairest flower of womanhood

e’er seen in Christom’s vasty lands.

The words rang unbidden through Rhian’s memory. She wondered if Gawain knew that particular poem. He certainly seemed ready to confirm its praises. She should have felt reassured by this. She was certainly in need, and she could think of nothing she had done to deserve what she had come to, but she could not bring herself to take heart.

‘She is learned, as well,’ Gawain was saying, warming to his theme. ‘Schooled in Greek and Latin, and familiar with poets and writings in both languages. She is perfectly matched with her husband in this respect. Arthur seeks to rule with learning and follow the Roman traditions of laws and letters. It is a good way. It is a better way…’ but his words trailed off and all at once, the road ahead seemed to take all his concentration. They had come to level ground again, and the trees here were younger and thinner. Patches of meadow grass sprang up between the gnarled trunks and the bird calls grew softer and at last, they broke the treeline, emerging, blinking into the sunlight of a marshy meadow land dotted with white and yellow flowers and smelling of damp grass and warmth.

Rhian opened her mouth to ask Gawain to continue, but then he reined his palfrey back, causing Gringolet to check his step. Rhian pulled Thetis up as well, and she followed Gawain’s gaze. Ahead, where the trees began again, there rose a thick column of dark smoke, dispersing to a black mist on the faint breeze.

‘What is it?’ she asked, seeing how Gawain’s face had grown suddenly grave.

‘That smoke is too heavy for a camp or a charcoal burner,’ he said. The palfrey danced impatiently under him, and Gawain patted it automatically, but he did not look away from the smoke. ‘There is no village or town in that direction. I do not like it.’

Without another word, Gawain urged the palfrey forward, leaving the road for the muddy meadow and taking his direction from the smoke plume. Gringolet lifted his hooves high and fastidiously to follow. Rhian and Thetis had little choice but to do the same.

The trees soon closed in around them once more, making it impossible to ride, and they both dismounted to lead their horses, pushing aside whip-like branches and directing their paths around decaying logs and pools of standing water. Rhian could not see the smoke now, but she could smell it, strong and acrid, and wrong somehow. It did not smell like a friendly hearthfire, nor did it carry the tang of the forge or the kiln. The birds overhead had all gone silent, and the only noise was the squelch and crackle of their passage.

No. Something else.

Rhian strained her ears, and heard a vague and distant crackling noise that should have been familiar, but that she could not make her mind identify.

They came to a narrow and rutted track, an offshoot of the main road, so little used that the forest plants were already beginning to sprout along its length. Gawain held up his hand, signalling her to halt. The scent of smoke had grown stronger, and the crackling, Rhian realized, must be the sound of the fire that made that smoke.

Gawain peered through the trees across the track. Rhian could see little through the greening branches, only some dark shapes that could have been anything from standing stones to an overgrown Roman fortress.

‘Wait with the horses, lady.’ Gawain did not look back at her as he spoke. He did, however, loosen his sword in its sheath.

With the smell of smoke and the sound of fire in the wind, and the knowledge that the Saxons were planning to begin their wars once again. Rhian did not want to walk forward to find out what was burned in these woods, but neither did she want to stand here alone.

She covered her fear in bravado. ‘You urge me to follow the example of Queen Guinevere. Would she remain behind at such a time?’

He turned to stare at her. She made herself look determined, although inside she was beginning to feel ill.

But her countenance must have been strong enough. ‘Agravain is ever reminding me to guard my tongue more closely,’ Gawain muttered. ‘Did you bring a spare bowstring?’

‘I did.’

‘Then restring your bow, Lady Rhian, and come.’

Quiver and bow slung over her shoulders, Rhian followed Gawain through the trees. They had left the horses tethered by the track. Gawain moved cautiously, like a man hunting, peering through the trees and scanning the ground before he took his next step, and she copied his gait and demeanour. The day was now far too warm, and far too quiet. The smoke took on the sweet smell of cooking meat, and the tang of fresh blood. Rhian’s mouth went dry. Behind her, the trees seemed to whisper uneasily. Ahead, the fire crackled and hissed.

Gawain pushed back a final screen of brambles and froze. Through the leaves Rhian saw what made the foully-scented smoke.

It had been a croft. There were countless such on the fringes of the woods. Several families had raised pigs here, perhaps some sheep. They had cleared some little land to put under the plough. If they prospered, more families would join them and perhaps in time they would become a village.

Or they would have, if fate had blessed them. Instead here was a scene of havoc. The cots and outbuildings had collapsed into ash and char. Coals still glowed among the black and shattered timbers. A piebald sow lay sprawled on the churned ground, slit from throat to belly so that its entrails spilled out into the ash among the shards of smashed pots and buckets. There would be worse under the timbers, Rhian knew that in the pit of her heart.

Without a word, Gawain walked forward into the chaos. The cleared ground had been churned into a sea of mud. Lumps of char and streaks of ash and blood were trampled deeply into it. This had been the work of men with horses. The marks of hooves as well as sandals and boots showed clearly on the ravaged ground. Despite the sound of the smouldering fires, the place seemed strangely silent. There should be more noise, Rhian thought, absurdly. There should be echoes of the screaming that had surely happened here, of the shouting and the pleas. There should be something of the life, of the voices, to remain, not just silent patterns in the earth and wisps of smoke to be blown away on the wind.

Gawain picked his way through the smouldering ruin to the wreck that had once been a cottage. His back stiffened and he spoke quietly, but Rhian heard every word.

‘They did not spare the children.’

Rhian crossed herself automatically. Mother Mary pray for us…

Gawain still cast about the ruins. Overhead a raven croaked. Fear took Rhian, although she could not say why. The horror here was done.

But movement flickered in the trees and the wind blew. Rhian’s eyes stung as the fresh ash touched them and through the tears she saw a shape standing at the edge of the clearing, great and green, a giant man leaning on the haft of a battle-axe nearly as tall as Gawain’s shoulder. She saw another man, this one pale as milk and bright as brass, carrying a sword smeared red and black from its work, and that man crept out of the ruined cottage, and slipped up behind Gawain and raised his blade high.

Gawain straightened up and the ghostly sword slashed at his torso. A second ghost fell, clutching its belly, and that ghost was Gawain.

Rhian’s hand flew to her mouth, but the vision was gone, and there was only Gawain, and the noises of the forest. A bird whistled overhead. A coal fell from a roof-timber to the ground. Both the Green Man and the raven were gone.

Gawain was staring at her.

‘I saw…’ she croaked. ‘I thought…’

‘Rhian,’ murmured Gawain. ‘Get to the road and free the horses. Do not look back.’

Rhian nodded and tried to comply. Behind her, she heard the rasp as he pulled his sword from its sheath and fear shot through her. She did not look back, but concentrated on the way forward, trying to remember her woodcraft and slip through the trees, but her fright made her clumsy. She tried not to think of the Green Man. Why should she see him again? Why now in this ruin? What was that ghost that had felled Gawain? Was it a warning from the Holy Mother, or was it the work of the Devil?

Collect yourself Rhian, you’re useless this way.

She reminded herself how to step softly, how to avoid branches rather than plough into them. It was then that she heard the bird call again, and this time she could hear it was not a true bird.

‘Run!’ shouted Gawain.

Rhian hiked up her skirts and obeyed. She crashed through the sea of branches and bracken, every twig becoming a claw clutching at sleeves and hems to hold her back. Behind her, the world exploded into noise such as only humans could make – the hoarse cries of men’s voices among the crash of branches.

The clash of metal.

Rhian looked back without thinking. Three men burst from the forest, short swords in their hands and caps of leather and bronze on their heads. One of them looked at her and his pale eyes glittered as he charged.

‘Run!’ bellowed Gawain again, and he flung himself against the marauders.

The Saxons were not expecting such a fierce attack. They fell back before Gawain’s longer sword and reach. But that advantage would not last, not in the trees. Gawain slashed like a madman, driving the Saxons back before him, not truly landing any blows, just keeping them busy.

Keeping them busy so she could get away.

Get to the horses, get to the horses! she cried in her mind, demanding her feet to flee, despite what she saw. Gawain was fighting to keep her free, and if she stood there, she would not remain so. When he broke free (and he will break free, he must break free), she needed to have the horses untied and ready so they could outrun the surviving Saxons.

Unless…

Metal glinted through the trees ahead of her and the sound of a horse’s angry scream cut through the air. Rhian’s madly beating heart filled her throat.

Unless they had already found the horses.

Instinct took over all conscious thought, and Rhian measured her length in a patch of unfolding ferns. Sheltered by the bracken, she pressed her hands over her mouth, trying to stifle the harsh sound of her breathing. The noise of the battle behind gave her some cover as did the screaming and thrashing of a maddened horse before her. She stared out through the screen of delicate leaves and stems and tried to quell her rising panic.

The Saxons had found the horses, and had put three men to guard them. The guards were greedy though. Goods from the saddlebags were strewn on the ground. One of them also apparently had tried to ride or handle Gringolet, and now the charger was doing his best to bedevil them. He bucked and reared, flailing out with his hooves, while two of the men tried in vain to catch his swinging reins and a third shouted and cursed in their harsh tongue. He had his sword out and was staring into the trees, trying to see through to the melee near the croft, to see if the wrong person had broken free of it.

In that chaos, Rhian saw her chance. She unslung her bow and reached for an arrow. Moving slowly, she pushed herself up onto one knee. Her own soft noises were masked by Gringolet’s outrage, the Saxon’s cursing and the clash of metal and splintering of wood as she pulled an arrow from her quiver, and nocked it into her string.

The Saxon with his sword drawn stood near the treeline. She shifted a little to get a clear line of sight.

It is just like a deer. It is just like a quail. Breathe slowly.

It is a deer. It is not a man. I am not about to kill a man.

Rhian drew the string back to her ear. She sighted along the shaft. Thetis, answering Gringolet’s distress, backed and swung her head, trying to free her reins from the branch where she was tethered. The palfrey whickered, the men shouted at one another. Gringolet reared again. In the woods, Gawain’s voice rang out.

The Saxon turned broad towards her, and Rhian loosed her arrow. It flew straight and true, without a sound, and plunged into the Saxon’s belly. He looked down, surprised to see this unnatural limb that had somehow sprouted from his body. Rhian, breathing now as if she had run a mile, drew another arrow. The Saxon she had shot toppled to the ground, screaming as the pain took him. Rhian nocked the fresh arrow. One of the remaining Saxons shouted to the other. Abandoning the harried and harrying Gringolet, he sprinted to his comrade’s side. Rhian drew back her bowstring and waited. The Saxon’s sword was in his hand and he turned his back to the trees, just for an instant, to shout to the other to leave the maddened horse and come to see. Rhian took her aim again, and again let go the string. She had meant the shot to take him between the shoulder blades, but as the arrow flew, he turned, and it was only luck that he was just a little too slow. The arrow drove itself through his arm and into his side. He dropped instantly, rolling and clawing at the wooden shaft. The third man saw his companion fall and stared at the woods. Gringolet reared again, pawing the air. The Saxon had wit enough to jump back. Rhian fitted a third arrow to the string.

She did not have a chance to fire. The man fled into the trees on the opposite side of the road, not even bothering to draw his sword. With the last Saxon gone, Gringolet calmed down, stamping and whickering but no longer so wide-eyed. His ears tipped forward again, alert, not laid back in fury. His calm eased Thetis and the palfrey and they quieted, easing their stamping and their calls.

At their feet, the men Rhian had shot screamed, their cries growing hoarse and choked with tears.

Rhian lowered her bow, letting the unshot arrow drop from the string. Her hands shook and despite the heat of the day, she felt cold. It was not until then that she realized the noise of the fight behind her had ceased, and footsteps now rustled leaves and undergrowth as they approached.

Rhian flattened herself against the ground again. She could not see clearly into the depth of the wood, she could not take aim, even if she could steady her hands again. The screams of the wounded men confused her mind. She could only huddle in the mud and pray for steadiness and silence. It would be Gawain, it must be Gawain, because if it wasn’t Gawain, she was lost.

The footsteps broke through the bracken and settled into the mud. Rhian dared at last to lift her head. In front of her, Gawain stepped from the woods to the track, his sword in his hand. He looked down at her handiwork, and with two swift strokes, brought the silence Rhian had craved but a moment before.

Rhian pressed her face against her sleeve, shuddering, until she could remember that what Gawain had just done was merciful. Those men were already dead; now they were out of pain.