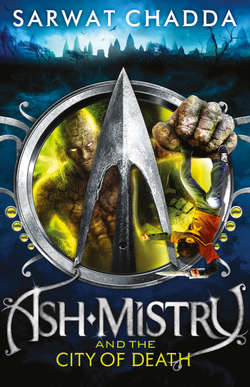

Читать книгу Ash Mistry and the City of Death - Sarwat Chadda - Страница 16

Оглавление

shoka gazes down the hill. A few fires still burn within the village, edging out the cold desert night. Somewhere in the darkness a bullock grunts and a baby cries.

A dozen or so squat mud-brick dwellings. A fenced-off corral for the cattle. Chickens squawking within the sheds. Fields with dried-out gullies and meagre crops. To the north squat the domed grain stores. How many such villages has he visited? How many fires has he lit? How many cries has he silenced?

Not enough. Not yet.

His band swells with each passing victory. Soon it will be an army. For Ashoka has dreams beyond village raids. This is how kingdoms begin.

He thinks about his father, a king, and his older brothers. They have grand palaces and dine off gold plates while he haunts the desert, eating with his band of brigands. His father laughed when Ashoka demanded his crown. How often was he laughed at, dismissed? Now they laugh no longer. They scream. If he cannot have their respect and love, he will have their fear.

Soon, the old palace will echo with wailing women, he thinks. That crown, and others, will be mine. He wonders how the old man sleeps, knowing his son is out here, carving out a kingdom of his own.

His men wait impatiently, like dogs eager for the hunt. They check their weapons, adjust their armour, ensuring helmets are fixed and there are no loose straps. But Ashoka expects little resistance. This will not be a battle – not against unarmed, unsuspecting villagers. This will be a slaughter.

His horse whinnies and stomps its hoof; it senses the coming bloodletting. Ashoka pats its thick neck. He himself wears a mail coat over his silk tunic and heavy cotton pantaloons. His boots, stiff leather, creak in the stirrups. A bright red sash lies across his waist, a jewelled dagger tucked into the cloth. Hanging from his saddle is his sword, a single-edged talwar with a gold-bound hilt. Which chieftain, which prince, did he slay to possess it? He cannot remember; there have been so many.

The jangle of reins and the snort of another steed snaps his attention back to his men.

A sleek mare with a high arching neck and white mane bound with silver and silk trots up beside him. The rider is clad in scales, and the sabre on her hip is sheathed in green crocodile skin. She doffs her helmet, and her emerald eyes shine in the moonlight.

“The men are ready,” she says.

Ashoka observes her. She leans over the pommel, waiting in anticipation, her forked tongue flicking along her fangs. Her cobra’s eyes do not lower; she defies where others would bow and kneel. Perhaps that is why she has risen so rapidly in his command. And why should she bow? Is she not royalty herself? Was not her father a great king?

“You have done well,” he says.

“My lord.” She bows, almost. “I am but your servant.”

“Ha! Servant? I doubt anyone could command you. You are terror made flesh, Parvati.”

She smiles, a rare thing, then looks down the slope. “Why this particular village?”

“Their landlord defies me. He refuses to pay tribute and so must be punished.”

“Shall I send a detachment to raid the stores?” She points towards the row of round huts some distance away. “They will be full of grain this time of year.”

“No. Burn them. The message will be clear. Defy me and you will be annihilated.”

“And the captives?”

“What captives?” Ashoka draws his own sword. “I want no survivors.”

“Slaves could be sold, my lord.”

Ashoka stands up in his stirrups and turns to his warriors. “Listen to me,” he shouts. He sweeps the blade down towards the village. “You are my jackals. We feed on blood and the dead. No survivors. Kill them all!”

Howls fill the night. Then the line of horsemen descends the slope, drawing their weapons, and suddenly the night is filled with the thunder of hooves and battle cries. The moon shines on swords and spears and axes, each one sharp and notched with heavy use. Chariots – light wicker contraptions drawn by pairs of steeds – rattle and bounce over the uneven, rocky terrain. A driver weaves his team through a gap between two sandstone boulders as his passenger nocks an arrow. The cavalry formation fragments as each man races his companion, eager to be the first to kill. Ashoka whips his horse and it froths at the bit, neighing with savage delight. He grins and his heart soars, a passion too primitive for words, so he merely howls as the wind rushes in his ears.

The village stirs. Men stumble from their doors, bewildered and still half asleep. A dog races up to him, but is crushed under the hooves of his horse. The steed vaults over the low defensive wall and Ashoka catches the open-mouthed shock of a villager’s face before he drives the tip of his sword into it. He twists his wrist and the sword tears free. He does not even turn to look back.

Women run out, clutching screaming children and babies in their arms. They flee into the darkness. They will not escape. With a nod, three of his horsemen break off in pursuit.

He sees Parvati leap from her steed as it takes a spear in its chest. She turns in the air and her sword flashes. A head leaps off a pair of shoulders, trailing a ribbon of blood. She has not yet touched the ground. Her eyes burn with demonic light. Men fall beneath her blade like wheat beneath a reaper’s scythe. She does what she does best: end men’s lives.

Ashoka drops from his horse and sweeps his weapon across a man’s throat without pause. He rams his shield into the face of another as he charges into the melee.

A hammer slams into his wrist knocking his sword away. He spins and sees a huge, oak-chested man wielding a heavy wooden mattock. The man is covered in minor cuts, but swings the hammer with bone-shattering power. A soldier runs to Ashoka’s defence, then collapses as a single blow flattens his skull.

Ashoka discards his shield and leaps at the villager. Both fall and scrabble in the blood-soaked dust. He digs his fingers into the man’s neck, squeezing—

“Ash!”

Ash squeezes the throat of his enemy as other soldiers grab his arms to try and haul him back. The big, fat villager’s face turns red and his eyes bulge.

“Ash!” a girl screamed as she hung on to his arm. She wept and screamed again. Is she the man’s daughter? She is nothing. She is—

“Lucky?”

Ash dropped his grip and his dad gasped. There was a bruise over his cheek and he lay there, coughing and clutching his ribs. Had Ash punched him?

“Oh God, Dad, I’m so sorry.”

His mum switched on the light. Ash’s bedroom was wrecked. His books had been thrown everywhere, the chair legs were snapped, and there was a fist-sized hole in the cupboard door.

Had he done that in his sleep? Ash stumbled back on to his bed. “I’m so sorry.”

But no one listened. Mum was kneeling with Lucky beside Dad as his father struggled to breathe. Purple finger marks surrounded his neck.

Ash stared at his family and met Lucky’s gaze. She stared back at him with horror and disgust. Her eyes were red with tears, but her face was hard and pale. All she could do was shake her head.

He couldn’t bear to look. Instead he covered his face with his hands and sank down with a groan. What was happening to him?