Читать книгу Contested Bodies - Sasha Turner - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction: Transforming Bodies

Suspended midair by one arm tied to a rope draped over a pulley, an unnamed African captive faced her last torment. For three weeks in the month of December 1791, she was flogged repeatedly for refusing to dance for the amusement of her captors. For about half an hour, the young girl, who was about fifteen years old, hung from her limbs, bruised and naked. Repeatedly she was whipped, hoisted, and released, her head falling inches from the ground. Her captors watched, mocked, and laughed. Several times during her ordeal, her tormentors changed her position, hanging her by each wrist, then by both hands, followed by each ankle, and finally by both wrists again. After her punishers satisfied their appetites for cruelty, they released her and instructed her to return to her quarters. From her weakened, terrified state, she collapsed, never to rise again. For three days, the unnamed girl writhed in pain as her now disfigured hands, swollen legs, and battered body trembled.1

The story of this unnamed fifteen-year-old girl was one of several accounts William Wilberforce recounted in his numerous speeches before the British Parliament persuading it to abolish the slave trade. Unlike many of the other cases Wilberforce brought to the attention of the House of Commons, this one drew national interest. Wilberforce narrated a truncated version of the brutal fate of the fifteen-year-old before the Commons on Monday, 2 April 1792, and by Tuesday, several British newspapers published the tale of the girl’s suffering. Almost two months later, on 7 June, Captain John Kimber of Bristol, the orchestrator of the girl’s punishment, faced trial for murder. The court hearing and subsequent not guilty verdict sensationalized the case, drawing further attention to the cruelty of the slave trade and the lack of justice for captive Africans.2

In the version he rendered before Parliament, Wilberforce detailed not just the manner in which the youngster was punished but also the reasons for the sentence she received and what he imagined were her feelings after the ordeal. According to Wilberforce, the young girl suffered from a disorder, which he refused to name. (Court testimonies suggested it was gonorrhea.) “Out of modesty,” he explained, she stooped down and tried to conceal her naked, infirmed body. The girl’s actions enraged Kimber, who exacted revenge by ordering her to be tied up naked as he whipped her. From Wilberforce’s account, the humiliation she endured was greater than the physical inflictions she sustained. From “the shame she suffered, she fell into convulsions, and died within three days.”3

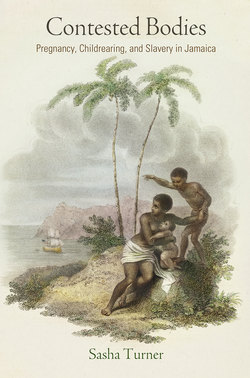

In addition to the inhumanity demonstrated by Captain Kimber and his crew, Wilberforce found this case compelling because of the gender and age of the victim. His emphasis on her efforts to conceal her naked body, and that she died from shame rather than from her physical injuries, were keystones in his argument. He used such details to argue that African females embodied feminine virtues, which he and other late eighteenth-century British reformers promoted as necessary for the unfree inhabitants of the West Indian colonies to possess in order to transition from slavery to freedom. The reproductive bodies of female slaves were the vessels through which abolitionists articulated the pathway to freedom. Modesty and shame became the recurring descriptors that newspaper writers used to describe the unnamed victim. The Evening Mail speculated, for example, that she tried covering a body that was maturing from girlhood to womanhood. The newspaper intimated that she was at the beginning of her menstrual cycle, when it described her as suffering from a condition “incident to women about that age.” Additionally, in an abolitionist cartoon painted by Isaac Cruikshank, the artist extended the portrayal of the girl as a virgin. The running title of his painting, reproduced in Figure 1, described her as being ill treated for her “virjen [sic] modesty.” In both pro- and anti-Kimber accounts of the trial, witnesses, including Thomas Dowling, the surgeon of the ship who brought the case to Wilberforce’s attention, testified that she suffered from gonorrhea.4 Wilberforce did not disclose what affliction plagued the girl. Exposing a gonorrhea diagnosis could betray his efforts to call attention to slavery’s assault on black women’s virtue and purity. Abolitionists like Wilberforce wanted to prove how slavery assaulted the body and undermined the morals of captive women, with the result that they became barriers to the natural reproduction of West Indian slaves.

The victim’s age and sexual innocence were therefore of strategic interest to Wilberforce and fellow campaigners, whose proposals for abolition focused on the reproductive potential of captive women as a means through which colonial improvement and eventual freedom could be secured. Descriptions, such as those published by the General Evening Post that focused on her “innocent simplicity,” aimed to do more than elicit sympathy from Parliament or the masses. They were a central pillar in the arguments forwarded by British reformers on how to end slavery. Petitioners who spoke in the parliamentary debates that continued on 23 April 1792 centered their appeals on strategies for abolition. Henry Dundas, secretary of the Committee to Consider Measures for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, stressed the need for gradual, not immediate emancipation. In consideration of the potential financial ruin to West Indian merchants and planters due to the loss of labor, Dundas and other members of his committee argued that time should be given to raise self-reproducing laboring populations to carry on the work of the sugar plantations. This plan could succeed only if Parliament allowed the trade to continue for a predetermined period, while stipulating and regulating the age and gender of captive Africans. Importing young females within their childbearing years would generate self-sustaining populations, and over time, it would render the slave trade unnecessary. Dundas’s proposal to extend what he described as a vicious, inhumane system of trade contradicted the humanitarian grounds of abolitionism. Yet Dundas had the support of several members of the committee, including William Wilberforce, who in his writings and speeches offered a similar plan to manage the reproductive lives of captive women as a route to freedom.5

Figure 1. Isaac Cruickshank, The Abolition of the Slave Trade; Or, The Inhumanity of dealers in human flesh exemplified in Captn. Kimber’s treatment of a Young Negro girl of 15 for her Virjen Modesty (London, 1792). Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs.

The paradox of abolitionists’ quest to save the hapless victims of the slave trade but not without ensuring that the sugar plantations maintained their productivity is one of the enigmas Contested Bodies examines. Using the body as its conceptual frame, this book explores how abolitionists perceived and represented young, black female bodies, and in particular, how they legitimized and sought to extend colonial rule and the benefits it generated to the mother country by controlling these women’s reproductive lives. By insisting that the imperial government and West Indian planters reform the working and material conditions of female slaves to enable them to reproduce the laboring populations, abolitionists tied abolition to women’s reproductive ability. Boosting slave population growth would not only end colonial dependence on an immoral and inhuman trade. More important, it would also produce children whose undeveloped minds and bodies could be fashioned into subjects that embodied the industriousness needed for the continued success of the colonial economies. In other words, these reforms would make slavery obsolete but improve the moral fiber of the colonies without jeopardizing British colonial goals or the fortunes of its investors. Stimulating population growth was therefore not just about ending slavery; when viewed in the context of British colonialism it was also about cultivating moral and industrious subjects. In following this strategy, abolitionists linked abolition and colonial reform to the reproductive lives of enslaved women.

Examining how Europeans used African-descended women to secure their interests is not new to studies of sugar and slavery in the colonial Caribbean. Beginning in the 1970s with the pioneering work of Lucille Mathurin Mair and continuing throughout the 1980s and 1990s historians debated the roles and responsibilities of women during Caribbean slavery. These historians have taught us much about the importance of sexual difference in determining the divergent demands and experiences of labor, punishment, resistance, sexual relations, family life, rewards, and privileges during slavery. In this body of work, gendered experiences were rooted in a person’s anatomical sex, but were distinguished further by color, race, and class.6

Although these approaches have revealed much about the divergent experiences of enslavement, the category woman as an analytical framework has not allowed for sufficient consideration of how the perceived abilities and prescribed treatment of the body determined how enslaved subjects were discoursed upon, labored, and disciplined and how they resisted. Thinking of enslaved people as having bodies that could be adorned, experience pain and pleasure, reproduce, and express desire, for example, allows us to access alternative experiences of slavery, even among members of the same sex. Dressing the body, styling the hair, and dancing communicated gender difference that complicated sexual difference.7 Examining slavery through reproductive bodies reveals not only how the lives of women differed from men’s. We also learn about the divergent experiences among women. Most obviously, conceiving and bearing children placed demands on and allowed childbearing women to care for their bodies in ways that infertile women could not. The reproductive body was essential to differences in intimate experiences among enslaved women.

In investigating abolitionist insistence that sugar planters promote and manage biological reproduction among their slaves, this book places the body at the center of its analysis. Using the body as the main investigative frame requires probing the representations and competing meanings given to the body and its capacities, the social relations and cultural ideals and expressions people created around the body, and how the body’s abilities and disabilities disrupt assumptions and restructure lives and beliefs. A body-centered approach explores prescriptions made about the body and its functions, its uses, treatment, and care and who benefits from its abilities. It requires recognition that the material body exists as an entity susceptible to illness, infertility, and death, despite human intervention and independent of meanings given to it. A body-centered approach is also concerned with understanding how ideas about the body determined people’s lived experiences.8

More concretely, Contested Bodies examines how abolitionist activists portrayed the bodies of enslaved women and children, and how such representations gave meanings to the body, and created a blueprint for what constituted proper treatment for young black women. As conduits for abolition, reform, and black citizenship, the laboring and reproductive bodies of enslaved women and their offspring were vulnerable to new labor and punishment regimes as well as care and medical interventions. In the abolitionist era, fertility and age, in addition to sex, determined the treatment and uses of bodies. On Jamaican sugar plantations where planters implemented “reproductive interventions” or ways of manipulating women’s fertility, the lives of mothers and their children were transformed.9 Transformations in the intimate and working lives of the enslaved, particularly women and children, constitute a second key theme that runs through this book. These transformations were punctuated, however, by conflicts between abolitionists, on one hand, who claimed authority to define the treatment of female slaves and prescribe the uses of their procreative abilities, and slave owners, on the other, whose ownership of slaves invested them with rights to wield power over women’s bodies.10

Abolitionists were only one group among many who were interested in the bodies of enslaved women and their children. Others included the imperial government, the local government in Jamaica, planters, doctors, and enslaved people themselves. A third task of this book, then, is to investigate how abolitionist representations and prescriptions for the reproductive enslaved body conflicted with those of other parties who owned female slaves and were financially invested in fertility and child-rearing practices. Contestations over the portrayals of enslaved women’s bodies, as the book’s title suggests, emerged between Jamaican slaveholders and abolitionists. Abolitionists had humanitarian and colonial concerns, while planters were interested in continued returns on their investments.

Representations of the capabilities of black and female bodies further diverged from what estate managers did on a daily basis to manage young enslaved women. Slaveholders depicted female slaves as robust and fertile, and argued that population decline resulted from women’s promiscuity and imbalanced sex ratios instead of overwork and brutal punishment. While these depictions were obstacles to reforming the medical care extended to women and how they were disciplined, masters at times tailored the management of their female workers around the physical manifestations and medical complications of pregnancy and childbirth. Planters revisited their labor practices and methods of disciplining workers because of abolitionist pressure and imperial mandates; but they implemented reforms according to the needs and interests of their property.11 The division of labor observed on the plantations was not simply one between males and females, or between African born, Creoles, and coloreds. Rather, workers toiled according to bodily assessments, including reproductive ability and disability as well as physical development, size, shape, and weight.

A conceptual approach that focuses on the body is useful in challenging generalizations about the sexual division of labor because it requires us to examine the organization of enslaved people’s lives and labor according to specific bodily functions and the meanings given to them. Examining the womb as vital to the wealth and power of Jamaican slaveholders and future productivity of the sugar estates extends the conversations beyond sexual difference. Viewed from this perspective, the assumption that during the abolitionist era, circa 1780–1834, that women were no more sheltered from hard labor or cruel punishment than their predecessors were, is not self-evident. Rather, field and factory workers labored according to the subjective assessments planters made of female body mass and stages of pregnancy, as well as the physical and mental maturity of young people. Studying slavery through differently abled bodies counters previous conclusions that, with the exception of skilled and elite workers, such as drivers and housekeepers, labor roles were “gender blind.”12 Concerns for biological reproduction during the abolitionist era transformed both planter assessments and women’s experiences of plantation work.

In using a body approach, this book builds on the work of historians Deborah Gray White, Marie Jenkins Schwartz, Jennifer Morgan, Stephanie Camp, and Deirdre Cooper Owens that explores female biological life cycles as well as the construction and use of the female body as a source and site of pleasure, medical experimentation, and disease during slavery.13 Showing how women’s childbearing ability was essential for creating gendered racial differences under slavery, Morgan’s work has been especially generative of the questions at the center of this study. How and with what outcome did abolitionists use the reproductive and maturing body to construct and legitimize a gradual path to ending slavery? How were these bodies used to determine the position and future of the enslaved within the colonies and the British Empire? How did the links abolitionists made between the reproductive body, abolition, reform, and citizenship shape the intimate and working lives of enslaved women and children as well as their parental, family, and community relationships?

In answering these questions, this study draws upon theories and perspectives from anthropology, material feminism, and gender studies.14 Studies on the reproductive lives of women and concomitant medical interventions and political and labor imperatives of modern Europe help to frame efforts to regulate and control black women’s childbearing ability and practices as part of a widespread conflict between doctors and midwives and childbearing women and workplace managers throughout the Atlantic world. From London and Paris to New York and Boston man midwives gradually displaced women attendants in the birth chambers of the city-dwelling elites. Driven partly by Enlightenment science, the advent of man midwives as the scientific authority over childbirth entangled reproductive concerns with articulations of national identities, gender order, and empire building. Eighteenth-century shifts away from viewing bodily difference between male and female as one of degree rather than absolutes required new theories. Male scientific authority over reproduction cleared a path for defining those differences and articulating them in ways befitting political and cultural needs. The ability of British men of science to explain the mysteries of the female body and reproduction reinforced gender hierarchies of male superiority that had hitherto exerted physical and moral power over women through virginity requirements, whipping for fornication, and limited legal protection for rape and domestic violence. Control over reproduction was another frontier in the quest for male domination over women’s bodies. Unlocking the secrets of women’s bodies also imbued national rhetoric of British progress, pointing out that scientific advances distinguished the practices of modern Britons from crude and superstitious practices of a bygone era and other cultures. Applying these frames to the colonial and slavery context affirms how reproduction was enmeshed in working out power and identity but also raises questions about how reproduction was complicated by the moral imperatives of abolitionism, the proprietary claims of slave ownership, and the resistance of the enslaved.

A closer look at benevolent reforms in other colonial settings also teaches us that, despite the criticisms and dissent of reformers, their medical interventions in the treatment of epidemic diseases like leprosy and cholera, for example, were not divorced from colonialism’s preoccupation with bringing subjugated populations culturally in line with the metropole, or refashioning them into workers and bureaucrats suited to fulfill the economic and political goals of the colonies. The colonial state intervened in the representation, regulation, and care of bodies it considered vital for the economic prosperity, political power, and ideological legitimation of colonialism. When applied to British slave colonies like Jamaica, abolitionist representation of enslaved women as degenerative people whose sexual perversions and gender aberrations, imputed by slavery, disqualified African captives from immediate freedom and subject citizenship and necessitated long-term reforms and gradual emancipation. Abolitionists envisioned that blacks would become culturally like metropolitan whites: Christian, married, industrious, independent, and responsible. Only then could their men become eligible to become subject-citizens.

British abolitionists grounded their campaigns on behalf of reproductive and growing bodies as fundamental for recasting the status of African-descended people from slave to free. But despite the humanitarian impulse of their campaigns, abolitionist pronatal interventions created new ways of subjugating the unfree inhabitants of the West Indian colonies. Returning to the unnamed girl in William Wilberforce’s speech, abolitionists found the story useful not only because it illustrated quite graphically the inhumanity of the slave trade but because it also allowed them to argue that modifications in gender roles and gender relations could set in motion political and economic transformations that could better serve British imperial ambitions. Preserving the sexual innocence of enslaved girls, socializing them to become wives, mothers, and homemakers as well as training boys to become fathers, heads of households, and industrious workers who were obedient to colonial authority had the power to transform debased, inefficient slave colonies into productive, well-ordered, and moral ones. According to abolitionist logic, balancing sex ratios, sheltering women from the brunt of field work, protecting pregnancy, improving maternal and neonatal care, and promoting Christian conversion and marriages were the necessary first steps for generating future colonial subjects, albeit in the very distant future. At the abstract level, reproduction was a powerful symbol of the creation of something new. Abolitionists aimed to tap into the transformative power of procreation. Exploring metropolitan goals expressed through their pronatal concerns and proposed interventions in intimate relations, health and healing, reproductive labor management, and child-rearing practices, Contested Bodies argues that the bodies of women and children were important sites of political struggles over slavery, abolition, and colonial reform.

At the same time, the conflicting visions of the slave body held by planters and enslaved people shattered the metropole’s romanticized ideals of women as wives, mothers, and homemakers and children as malleable clay, moldable into docile laborers and future subject-citizens. This study is not just interested in uncovering how abolitionists and planters projected their moral and economic ambitions onto the bodies of enslaved women and children; it is also concerned with how enslaved people contested the medical, gendered, and parental ideals foisted upon them. Reproductive concerns were not only essential to the social and cultural lives of the enslaved. By controlling childbearing practices, enslaved women had brief and informal access to power that temporarily inverted slavery’s white- and maledominated gender order.

Although enslaved people’s interests in healthy pregnancies and babies aligned with those of the slaving class, enslaved mothers, healers, family, and community members distrusted white medicine and benevolence. Rather, enslaved people insisted on practicing their own birth, healing, and childcare rituals that featured herbal medicine, fostered alliances between new mothers and self-selected caregivers, and preserved the authority of enslaved midwives and healers. The authority, social bonds, and cultural practices created around reproductive health and childbirth countered the imperialist and capitalist purposes abolitionists and slaveholders gave to birthing and raising children. By examining the struggles for the control of biological reproduction, this book illustrates how central pregnancy, childbirth, and child-rearing were to the abolition of slavery, the reorganization of plantation work, the discipline and care of slaves, and the fashioning of resistance, social life, and culture among the enslaved.

Contested Bodies therefore centers pregnancy, childbirth, and child-rearing practices as zones of conflict, in which abolitionists, slaveholders, doctors, the imperial and Jamaican governments, and enslaved people competed to control and regulate biological reproduction and determine who benefited from its rewards. Taking the 1780s era of abolitionism as a transformative moment in the lives of enslaved women and their children, the book examines reproductive interventions proposed by abolitionists and how they transformed, conflicted with, and shaped social customs, medical practices, labor, and punishment, as well as the relationships parents had with their children. The divergent claims on enslaved women’s ability to procreate defined the power struggles in the closing decades of slavery in Jamaica.

To understand why the 1780s marked such a major turning point in the lives of enslaved women and children, some knowledge of the earlier practices and material conditions of slavery is necessary. In framing laws that governed slave societies, slaveholding legislatures discontinued European practices of linking the status of children to their fathers and transferred it to mothers. Even though all children born to a female slave became her owner’s property, partus sequitur ventrem, slaveholders remained ambivalent about importing women and their attentiveness to childbearing. Over time, men and boys outnumbered women and girls in the transatlantic slave trade. Although scholars disagree on the reasons for and the extent of such fluctuations, most agree that the greater value planters placed on male workers played an important role.

Many planters were hostile, ambivalent, and indifferent toward pregnancy and childbirth among slaves because they feared it was a distracting, expensive, and uncertain method of replenishing worn-out and dead workers. Slave owners and plantation managers generally believed it was more cost effective to buy adult males imported via the transatlantic slave trade. Labor shortages and profit-loss calculations made planters reluctant to lose women’s labor during pregnancy and childbirth as well as the ten to sixteen years needed to raise children into capable workers. High infant mortality rates, in which less than half of Jamaica’s enslaved children survived into adulthood, also made investing in biological reproduction a gamble.

As a consequence of this unprecedented mortality, and well before the 1807 prohibition of legal slave trading, many Jamaican properties suffered from acute labor shortages. Workers were scarce because warfare and political instability sometimes made West African supplies difficult to procure. Precarious weather and Europe’s intercontinental wars also delayed the arrival of ships in West Indian harbors. Detained ships suffered from increased outbreak of illnesses and death among their already diseased, malnourished, and abused cargo. These trade complications negated gender preferences expressed by planters. Slim pickings also made those appearing healthy more expensive.

Scholars estimate that approximately 15 percent of cargo died before they arrived in the Americas. Among the dead captives not accounted for were those who perished during capture, or while traveling from their point of capture to the coast. Others died while they awaited sale and the boarding of slaving ships. At least 5 percent of those surviving the Middle Passage perished shortly after landing in the New World. Living for weeks in cramped quarters, soaked in blood, urine, feces, and pus and fed meagre, nutritionally deficient rations, many African captives arrived in the Americas diseased or debilitated.15 Captive women’s vulnerability to sexual abuse also increased the spread of sexually transmitted infections, like gonorrhea, which sometimes caused infertility. Others, like the unnamed fifteen-year-old girl on Captain Kimber’s ship, survived diseases and starvation only to die at the cruel hands of their captors.16 The abuse, neglect, and diseases from which women and girls suffered during capture and transportation meant that females landing in the West Indies were already reproductively challenged.

Workers, especially women, felt the burden of labor shortages as taskmasters allocated them to multiple jobs. During periods of extreme labor demands, like the sugar harvest, temporary hired workers or jobbers assisted with nonspecialized work. On some properties, workers had the assistance of labor-saving technology like horse-drawn plows and hoe harrows. Although women were the majority of field workers, they did not benefit from the introduction of new agricultural technology. For the few planters who invested in ploughs and harrows, their views of women as clumsy and incapable of operating machinery meant that male field hands were the main beneficiaries of mechanized agriculture. Hiring extra work hands and investing in expensive agricultural equipment, moreover, were not always compatible with the financial circumstances of estates or Jamaica’s soil and topography. This meant that women, who composed the majority of field workers and unskilled laborers around the sugar factories, had very few opportunities for a relaxation of their work routines. These factors combined to undermine fertility.17

The work rhythms of West Indian sugar estates, which are at the center of this study, were unrelenting. They made conception and pregnancy difficult and child-rearing burdensome. Workers toiled day and night, year-round, because planters feared idle hands made slaves rebellious and insolent. For six months out of the year, typically from January to June, workers kept busy with reaping cane and manufacturing sugar. For another four months they plowed the fields and planted, molded, and fertilized cane suckers. In between planting and harvesting, during the lull from June to September, workers built and repaired factory equipment and houses. If the January-to-June harvest season was quick-paced laborious work, the September-to-December planting season was slow and tedious but no less strenuous. A key difference, however, was that unlike the twenty-four-hour shift system of the harvest period, working days during the planting months more consistently started at sunrise and ended by sundown. Field workers experienced changes in labor demands based on whether planters replanted or “ratooned” canes. Fields rotated between the replanting of fresh cane suckers in cleared fields and ratooning, in which cane stumps were left in the fields to sprout the following season. Replanting consumed laborers as well as the financial resources of an estate. Ratoons saved on labor, since it relied on a natural regeneration process, but yielded less than newly planted canes. Labor routines relaxed or intensified according to the overall size and health of the workforce, the state of an estate’s finance, and whether planters replanted or ratooned.18 Under these demanding labor conditions, the vast majority of West Indian planters found it more effective to rely on imported workers and ignored the reproductive needs of women before the 1780s.

Work-related accidents and death rates peaked among workers during the January-to-June sugar harvest because sugar mills and boiling houses worked nonstop to prevent spoilage. The multiple and strenuous demands of harvest meant that concessions to workers, like expectant and new mothers, were even more limited. As well as organizing workers into three primary field gangs, some plantations also divided them into task gangs based on their perceived physical abilities and health. The first or great gang, dominated by women, performed the most demanding field tasks, like cutting, bundling, and carrying canes. Second gang workers assisted in tying and carrying cane bundles and fed cane stalks into cattle-drawn, wind, or water mills, which crushed the cane to extract its juice. Third gang workers removed residual trash called bagasse from the milling areas and brought them to the boiling house. Dried bagasse provided fuel for boiling the extracted cane juice. Because the sucrose content of sugarcane deteriorates soon after harvesting, the reaping, milling, and boiling of cane and cane juice had to be closely synchronized. Sugar mills and boilers therefore operated uninterrupted, with workers changing shift throughout the night to prevent canes and juice from fermenting.19 Summing up the intensity of the production process, one contemporary explained, “We keep about the works and the boiling of sugar the whole night, from which circumstance we commonly divide our gang into three spells of boilers, people to attend the mill, and to carry out cane trash.”20 Although female workers and young children played what planters viewed as unskilled, supporting roles as mill feeders and trash carriers in the sugar factory, they were no less affected by strict discipline of the harvest.

The unrelenting work regimes of the sugar plantations, combined with inadequate and nutritionally unsound diets, debilitating punishments, unsanitary living conditions, and poor medical care had fatal consequences for mothers and children. Enslaved women mothered few sons and daughters because of low fertility and frequent miscarriages. Of the children who survived their precarious gestation, more than one-half died before their second birthday. To secure the survival of their offspring expectant and new mothers had to strike a delicate balance between their physically taxing, quick-paced jobs and the demands of pregnancy and motherhood. Members of enslaved people’s communities helped to deliver babies and attend to the hygiene and medical needs of new mothers and newborns.

Despite the precariousness of motherhood, enslaved women and community members eked out a small measure of autonomy by having to fend for themselves with childbearing. Ironically, planter preoccupation with the productive rhythms of their estates freed women and community members from their oversight. Enslaved people therefore cultivated their own approaches to caring for mothers and their children. By the 1780s, when abolitionist activists articulated reform and abolition through women’s reproductive capacities, enslaved mothers and community members had already developed autonomous social networks and customs around maternal and infant care. These practices would become a central point of conflict between enslaved community members, planters, and doctors.

The links abolitionists made between emancipation and reproduction not only stimulated changes in how enslaved women and children experienced labor and discipline and gave rise to conflicts over how to care for the bodies of women and children. They also generated documentation that provides insight into enslaved people’s birth and maternal practices that previously had been absent from official records. Responding to abolitionists’ efforts to capture the inhumanity of slavery, the British Parliament created several investigative committees between 1789 and 1792. These committees were tasked with assessing the conditions of the laboring populations of Britain’s West Indian colonies.21 Witnesses were called from various branches of the slaving system and included slave traders, doctors, and planters. While such proslavery witnesses pathologized slaves and exaggerated their own benevolence, their disparagement of what they perceived as the unhygienic, medically unsound, and unsafe birth and child-rearing practices of the enslaved gives us unprecedented insight into enslaved people’s intimate relations, birth, and child-care rituals.

Witness accounts, however, must be read with great care and in the context of other sources, such as medical records and doctor correspondence. The number of those accounts grew because slaveholder interest in procreation, coupled with the rise of academic medicine, increased the presence of professional doctors in the colonies. Although medical practitioners sometimes aligned themselves with planters, they were also interested in professionalizing medicine in the colonies and published manuals and accounts of their observations and treatments. Physicians who discussed the changing health and treatment of the enslaved offer additional insights into pronatal interventions and help to counterbalance some of the self-serving reports given by parliamentary witnesses.

The process of ending British West Indian slavery was a long and tedious affair. Scholars typically divide the process into two phases. The first phase starts with the rise of abolitionism in 1780 and ends in 1807 with the abolition of the slave trade. The antislavery campaigns of the 1820s and the 1833 Emancipation Act mark the beginning and end of the second phase. This division reflects not only the split between activism against the slave trade and antislavery. It also signals differences in the nature of reforms, or amelioration. While the imperial Parliament gathered evidence on the inhumanity and immorality of slavery and the slave trade between 1789 and 1807, West Indian legislatures passed new laws aimed at ameliorating the material conditions of slavery. These laws focused on areas abolitionists singled out in their criticisms of the slave system as well as on matters planters worked out as important to improve slaves’ welfare. The new legislation, for example, required masters to provide slaves with food, clothing, housing, medical care, and religious instruction, as well as reward mothers with more relaxed work routines. The laws also made masters liable for negligence or excessive cruelty toward their slaves. The 1788 Act for “the better Order and Government of Slaves,” or the Consolidated Slave Act, in particular, gave bonded workers the right to seek legal redress by taking their cases to a justice of the peace, who was then required to convene a Council of Protection. This new legislation tasked councils with investigating and bringing enslaved people’s complaints before the Assize Court or Supreme Court.22

Perceived failure of amelioration led to the passage of the 1816 Slave Registration Act, which required planters to record the birth, death, sale, and manumission of their slaves. Although this act was a backdoor method of tracking the illegal importation of slaves, the registers it generated are invaluable to the historian for the rich demographic details they provide on fertility, infant and child mortality, and cause of death. Claiming that the situation of mothers and children remained unchanged, abolitionists shifted attention away from slave trading and mounted a more explicit attack against slavery in the 1820s. The British Parliament took a leading role in reforming the law of slavery by sending blueprints of ameliorative legislation to West Indian assemblies for local adoption. The lively debates in the Jamaican Assembly over the adoption of imperially mandated laws of the 1820s illustrate how the colonies worked out the details of amelioration and give us further insight into the perception planters had of enslaved women and children, and their place in the future of the colonies. The expectation that enslaved women would remain in perpetual bondage as brute workers conflicted with abolitionist insistence that reforming the condition of women and children was a stepping stone toward freedom.

Difficulties of legal enforcement have led historians to conclude that legislative reforms were ineffective.23 Admittedly, ameliorative laws and councils had very little effect because those charged with enforcing slave laws held investments in slaves and therefore had an interest in limiting enslaved people’s liberties. Moreover, slaveholders’ continued drive for capital gains through agroindustrial output conflicted with the need to relax the demands they placed on women, particularly those who were pregnant and were already mothers. Legislative reforms, however, created a new space in which enslaved parents and community members publicly avowed their social ties and articulated their discontent with continued threats against their friends and family. The limited prerogative enslaved people had to take their masters to court, for example, was a new freedom that many mothers and fathers capitalized on to protect their families. Court records are especially helpful because they bring to light the place of male relatives and friends in parenting and intimate relations. In this regard, they offset the accounts given by planters and doctors, which focused exclusively on women and children.

This study also relies on the more traditional sources used to capture the material conditions of slavery. Those include the correspondence of planters, the daily work logs, and inventories of slave populations that list workers’ sex, age, occupation, pregnancies, miscarriages, health conditions, work exemptions, and recent births. Examining these records using a body approach offers insights into how, for example, the physical and sexual development of young people and the changing contours, size, and weight of women’s bodies during pregnancy defined their particular experiences of labor and punishment. Studying a wide array of such documents from several sugar estates also shows us that reforms were neither uniform nor consistently implemented across all Jamaican sugar estates. Research into public records, like court cases and newspaper advertisements, also reveals that enslaved fathers and husbands played key roles in helping women to preserve maternal customs and to contest the intrusions slaveholders made upon their intimate and family lives.

Taken as a whole, Contested Bodies uses a wide array of sources to examine the struggles for the control, regulation, and rewards of biological reproduction as they played out in the working and intimate lives of enslaved women and children from the rise of British abolitionism in the 1780s to the end of slavery in 1834. Abolitionists, slaveholders, doctors, and the imperial and local governments, as well as enslaved men, women, and children, were locked in ongoing conflicts because they held contrasting views about how the young and female bodies of enslaved African-descended people fit into their goals. They disagreed on what these bodies represented and how they should be treated, used, and cared for. Studying these conflicts uncovers how the links abolitionists made between biological reproduction, abolition, and reform transformed the experiences of enslavement, and fostered new forms of resistance, social relations, and cultural life among the enslaved.