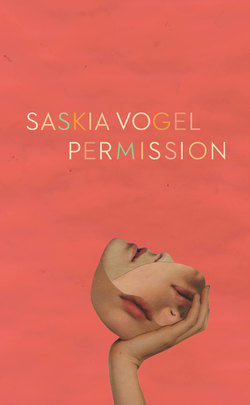

Читать книгу Permission - Saskia Vogel - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE HILLS WERE SLEEPING GIANTS, twitching as they dreamed. Each time they rolled over in their beds, maintenance crews arrived to fix the cracks in the coastal road, and the sea sucked stones from the shore. When the hills caught fire during the dry season, I stood at the cliffs watching helicopters lower their buckets into the water. I’d search for the pilot’s eyes as the chopper rose into the sky, up and over my parents’ house, hoping they were carrying nothing but water. Brush fire and broken roads were everyday dangers, like rattlesnakes and car crashes. I kept a packed suitcase in my closet, should the earth shake or fire jump the road. Even as a child, I knew the landscape would not hold.

The landscape brought other fascinations to my family’s front door. We would watch migrating whales logging or lunging in the coves. We spent the season counting and took our tallies to the interpretive centre, a squat building next to a lighthouse surrounded by a garden of native plants. Through Bakelite handsets, I listened to underwater recordings of whales, their haunted songs, their hearts. In the long silence between each slow beat, I’d take my pulse. I often returned to this quiet space, finding relief in the cocoon of a steady, even bass.

In another room, dioramas depicted centuries of cliff erosion in the area. Fifty feet, one hundred feet, gone. The present-day model showed the cliffs as they were. Nothing had crumbled in a long while, even in the landslide zones. But I knew what that meant. A crumbling was overdue. Before I grew old, the land would claim our bodies and we would rise again as ghosts. Ghosts, like the young woman who haunted the lighthouse. She had thrown herself off these cliffs when she was sure her sailor would never return. She entered oblivion to find him. It was the most romantic story I knew. I liked to imagine love’s oblivion. A yielding of the self to sensation, a sensation that belonged to the nights I fell asleep with my hands cupped between my legs, comforted.

On these nights, I was sure I could hear the lovers’ laughter rising from the waves. Their joy beckoned. Once I followed the sound to the end of the garden, through the fence and to the cliff, crawling under the rail, inching closer and closer, closer to the edge than I’d ever dared. Peering down the wall of sedimentary rock, I discovered a ledge. Huddled figures wrapped in a cloud of something cloying, like roses wilting in a bowl. Laughing as if their rock were the only rock that promised never to fall. Fall, fall, fall, the cliffs whispered. Dear God, If I fall, please let me die on impact. Paralysis would be worse than death, I thought, and it frightened me. I couldn’t imagine myself without this body, even though as a child I sensed its limits, the built-in obsolescence. The call grew louder, and eventually I stopped taking walks along the cliffs.

By the time I was ten, my father had had enough of my living in fear. He said it was not death that awaited me at the foot of the cliffs, but a beach. I could get anywhere, as long as I knew how to navigate my environment. I think he grew to like those cliffs so much because the longer we spent in that house, the less he seemed to be able to keep a grasp on us, especially on my mother, whose refusal to be pleased was a form of tyranny. The cliffs he could handle. Scaling the sedimentary rock, sliding down a steep and sandy path, he taught me about footholds and grips and how to read the stones. The sea at our feet, indifferent to us. It was a rocky beach, not suitable for swimming or sunbathing, most easily accessed by boat. On the shore: tide pools, sunbaked kelp, seal carcasses, cans eaten by the salty air, weather-beaten dirty magazines, traces of fire. I pictured the molten glow of midnight fisherman roasting their catch, wary of the siren’s song. Even the air on the beach was sticky.

I would linger by the spreads of nude women bleaching in the sun. That pleasing tension, the muscular contraction of the sea cucumber, the gentle suction of an anemone’s tentacles when I stuck my finger in the water, pretending I was a clownfish, impervious to its sting.

Rusty kelp beds broke the blue, red markers bobbed above where fisherman laid their traps. Down the crescent of our cove, my father and I scaled the lip of its rocky maw. When low tide turned to high, frothy waves crashed against the throat of the cave, and when they receded, they licked the pebbled floor clean. The first time I saw the cave and the rocky point, I refused to follow him across.

‘Don’t be scared,’ he said. ‘Just don’t fall.’

Fifteen years we climbed over that cave.

And then, one day, he fell.

I didn’t see it happen. He was ahead of me, and then he wasn’t. That’s what I told emergency services. There was a response boat. Helicopter. Harbour Patrol. Divers. They were out on the water until morning. We were told they’d stay in ‘search-and-rescue mode’ until ‘the victim’ was found. After the twenty-four-hour mark, they started to call it ‘body recovery,’ but even that search failed. I asked them what they were calling it now, but they would give no answer. They started passing the buck, each one telling me to ask another department.

In the aftermath, I spent most of my days at home with my hands pressed to the large glass panes facing our clear ocean view. When I had spent so long looking I could no longer tell sea from sky, my hands stayed put on the windowpane, feeling every vibration, every thud of wind. I was still in the womb when the shipping company they worked for moved my parents from Rotterdam to Los Angeles, but I was old enough to remember when they built it. Their dream home. How carefully they chose each detail, the joy they were able to take in it and each other. I didn’t understand why we needed to leave the small house with the floral wallpaper by the port, where we could see cranes unloading containers from cargo ships, and every day at dusk a man who skateboarded around the neighbourhood with a trumpet under his arm stopped to play ‘Taps.’ But when I first saw the house, it was unreal.

A great white box planted atop a bluff, a jut of land pushing into the sea, set apart from every other house on the street. Instead of sirens and trumpets, we heard peacocks and seals. The house was glass and steel and full of light. Once inside, you could see the ocean from just about any angle. At sunset the walls turned tangerine, then violet, before darkness arrived and gave us the stars. ‘Every day a love letter,’ my father would say, my mother in his arms, taking in the life they had built together. I preferred to think of them like this. Optimistic, trusting in whatever logic kept them from getting a divorce.

Standing at that same window, it wasn’t the ocean I saw but seams: silicone, grout, hinges, and brackets. All that was holding the house together and all the ways in which it could fall apart. Cracked Malibu tiles in the entryway, cracks running down the stucco walls. I inspected the silicone that held our kitchen sink in place, the build-up in the corners, the way the basin never really dried. Corrosion. I took the trash cans out of the cabinet under the sink and ran my fingers along the scar-like material holding it in place, feeling for edges that had unstuck themselves. Testing their integrity with my thumbnail, feeling sick when it slid underneath.

After my father disappeared, the Friday of Memorial Day weekend, my mother forgot to cancel the barbecue, which made for awkward conversations at the door. We didn’t invite anyone in but the caterer. I unplugged the phone. There was no reason for me to go back to my apartment in the city after the holiday weekend, so I waited a while, subsuming myself in her rhythm of sleep and reheated macaroni, marinated meat, and booze. The caterer had packed everything into single servings, some for the freezer, some for the fridge. You’ll need to eat, she kept saying. My mother split each serving in half, and when she handed me my plate she would say, This is no excuse to let ourselves go. Blanca cleaned up after us and made sure there was fresh milk for my father, as usual. After the milk went sour, Blanca asked where Mr. Jack was and my mother told her that he’d be back, but she must have asked around the neighbourhood because I heard her crying in the laundry room.

During these days, his absence led to a kind of ease between my mother and me, but we still didn’t find a way into conversation. What was there to say? He might still return. And when I thought, no, maybe he’s really gone, it wasn’t words that wanted to come out of my mouth, but screaming. Finger-pointing and blame. And if I started in on blame, I was afraid of what she would say. I would blame her for pushing him away, and she would point to my fear as the cause of his demise. When we’d exhausted each other, maybe we’d cry together, talk about the loss of a man who’d never been good at making room for us in his life. All of it was too much and too unpredictable. It was best to keep my mouth shut and wait.

Each night, we sat on the balcony and stared at the ocean. Each night, she’d go to the pantry and take out one cigarette from the ceramic jar marked ‘garlic.’ She’d drop the ash into a wet paper towel and toss the sooty lump in the trash can in the garage. She left no trace because she promised him she’d quit. One morning I woke to find an ashtray on the kitchen table and stale smoke in the air. I never loved her less than I did then.

It seems inevitable in the retelling. My mother and father playing house, building their lives and their love in the shape of something familiar, never stopping to question the structure, the structure not being able to hold. But really, I don’t remember much about those early weeks after he fell, how it went and why, apart from the forgetfulness – going to get milk from the kitchen but only managing to take a glass from the cupboard before being distracted by something else, and finding myself in another room wondering what the glass was doing in my hand. The crying that kept me from sleep, the thoughts that wouldn’t quit, guilt, resentment, the gape of loss. Day after day passed by, then June was over and I was still at my parents’ house. It’s easy to lose track of time in Los Angeles even when you’re not wondering where Dad is, whether gone means gone and what being gone means. The sun and sky are narcotic. Seventy-five degrees and clear afternoon skies by the beaches day after day after day.