Читать книгу Hit Refresh: A Memoir by Microsoft’s CEO - Satya Nadella - Страница 8

Chapter 1 From Hyderabad to Redmond How Karl Marx, a Sanskrit Scholar, and a Cricket Hero Shaped My Boyhood

ОглавлениеI joined Microsoft in 1992 because I wanted to work for a company filled with people who believed they were on a mission to change the world. That was twenty-five years ago, and I’ve never regretted it. Microsoft authored the PC Revolution, and our success—rivaled perhaps only by IBM in a previous generation—is legendary. But after years of outdistancing all of our competitors, something was changing—and not for the better. Innovation was being replaced by bureaucracy. Teamwork was being replaced by internal politics. We were falling behind.

In the midst of these troubled times, a cartoonist drew the Microsoft organization chart as warring gangs, each pointing a gun at another. The humorist’s message was impossible to ignore. As a twenty-four-year veteran of Microsoft, a consummate insider, the caricature really bothered me. But what upset me more was that our own people just accepted it. Sure, I had experienced some of that disharmony in my various roles. But I never saw it as insolvable. So when I was named Microsoft’s third CEO in February 2014, I told employees that renewing our company’s culture would be my highest priority. I told them I was committed to ruthlessly removing barriers to innovation so we could get back to what we all joined the company to do—to make a difference in the world. Microsoft has always been at its best when it connects personal passion to a broader purpose: Windows, Office, Xbox, Surface, our servers, and the Microsoft Cloud—all of these products have become digital platforms upon which individuals and organizations can build their own dreams. These were lofty achievements, and I knew that we were capable of still more, and that employees were hungry to do more. Those were the instincts and the values I wanted Microsoft’s culture to embrace.

Not long into my tenure as CEO, I decided to experiment with one of the most important meetings I lead. Each week my senior leadership team (SLT) meets to review, brainstorm, and wrestle with big opportunities and difficult decisions. The SLT is made up of some very talented people—engineers, researchers, managers, and marketers. It’s a diverse group of men and women from a variety of backgrounds who have come to Microsoft because they love technology and they believe their work can make a difference.

At the time, it included people like Peggy Johnson, a former engineer in GE’s military electronics division and Qualcomm executive, who now heads business development. Kathleen Hogan, a former Oracle applications developer who now leads human resources and is my partner in transforming our culture. Kurt Delbene, a veteran Microsoft leader who left the company to help fix Healthcare.gov during the Obama administration and returned to lead strategy. Qi Lu, who spent ten years at Yahoo and ran our applications and services business—he held twenty U.S. patents. Our CFO, Amy Hood, was an investment banker at Goldman Sachs. Brad Smith, president of the company and chief legal officer, was a partner at Covington and Burling—remembered to this day as the first attorney in the nearly century-old firm to insist as a condition of his employment in 1986 that he have a PC on his desk. Scott Guthrie, who took over from me as leader of our cloud and enterprise business, joined Microsoft right out of Duke University. Coincidentally, Terry Myerson, our Windows and Devices chief, also graduated from Duke before he founded Intersé—one of the first Web software companies. Chris Capossela, our chief marketing officer, who grew up in a family-run Italian restaurant in the North End of Boston, and joined Microsoft right out of Harvard College the year before I joined. Kevin Turner, a former Wal-Mart executive, who was chief operating officer and led worldwide sales. Harry Shum, who leads Microsoft’s celebrated Artificial Intelligence and Research Group operation, received his PhD in robotics from Carnegie Mellon and is one of the world’s authorities on computer vision and graphics.

I had been a member of the SLT myself when Steve Ballmer was CEO, and, while I admired every member of our team, I felt that we needed to deepen our understanding of one another—to delve into what really makes each of us tick—and to connect our personal philosophies to our jobs as leaders of the company. I knew that if we dropped those proverbial guns and channeled that collective IQ and energy into a refreshed mission, we could get back to the dream that first inspired Bill and Paul—democratizing leading-edge computer technology.

Just before I was named CEO, our home football team—the Seattle Seahawks—had just won the Super Bowl, and many of us found inspiration in their story. The Seahawks coach, Pete Carroll, had caught my attention with the hiring of psychologist Michael Gervais, who specializes in mindfulness training to achieve high-level performance. It may sound like Kumbaya, but it’s far from it. Dr. Gervais worked with the Seahawks to fully engage the minds of players and coaches to achieve excellence on the field and off. Like athletes, we all navigate our own high-stakes environments, and I thought our team could learn something from Dr. Gervais’s approach.

Early one Friday morning the SLT assembled. Only this time it was not in our staid, executive boardroom. Instead we gathered in a more relaxed space on the far-side of campus, one frequented by software and game developers. It was open, airy, and unpretentious. Gone were the usual tables and chairs. There was no space to set up computers to monitor never-ending emails and newsfeeds. Our phones were put away—jammed into pants pockets, bags, and backpacks. Instead we sat on comfortable couches in a large circle. There was no place to hide. I opened the meeting by asking everyone to suspend judgment and try to stay in the moment. I was hopeful, but I was also somewhat anxious.

For the first exercise Dr. Gervais asked us if we were interested in having an extraordinary individual experience. We all nodded yes. Then he moved on and asked for a volunteer to stand up. Only no one did, and it was very quiet and very awkward for a moment. Then our CFO, Amy Hood, jumped up to volunteer and was subsequently challenged to recite the alphabet, interspersing every letter with a number—A1B2C3 and so forth. But Dr. Gervais was curious: Why wouldn’t everyone jump up? Wasn’t this a high-performing group? Didn’t everyone just say they wanted to do something extraordinary? With no phones or PCs to look at, we looked down at our shoes or shot a nervous smile to colleagues. The answers were hard to pull out, even though they were just beneath the surface. Fear: of being ridiculed; of failing; of not looking like the smartest person in the room. And arrogance: I am too important for these games. “What a stupid question,” we had grown used to hearing.

But Dr. Gervais was encouraging. People began to breathe more easily and to laugh a little. Outside, the grayness of the morning brightened beneath the summer sun and one by one we all spoke.

We shared our personal passions and philosophies. We were asked to reflect on who we are, both in our home lives and at work. How do we connect our work persona with our life persona? People talked about spirituality, their Catholic roots, their study of Confucian teachings, they shared their struggles as parents and their unending dedication to making products that people love to use for work and entertainment. As I listened, I realized that in all of my years at Microsoft this was the first time I’d heard my colleagues talk about themselves, not exclusively about business matters. Looking around the room, I even saw a few teary eyes.

When it came my turn, I drew on a deep well of emotion and began to speak. I had been thinking about my life—my parents, my wife and children, my work. It had been a long journey to this point. My mind went back to earlier days: as a child in India, as a young man immigrating to this country, as a husband and the father of a child with special needs, as an engineer designing technologies that reach billions of people worldwide, and, yes, even as an obsessed cricket fan who long ago dreamed of being a professional player. All these parts of me came together in this new role, a role that would call upon all of my passions, skills, and values—just as our challenges would call upon everyone else in the room that day and everyone else who worked at Microsoft.

I told them that we spend far too much time at work for it not to have deep meaning. If we can connect what we stand for as individuals with what this company is capable of, there is very little we can’t accomplish. For as long as I can remember, I’ve always had a hunger to learn—whether it be from a line of poetry, from a conversation with a friend, or from a lesson with a teacher. My personal philosophy and my passion, developed over time and through exposure to many different experiences, is to connect new ideas with a growing sense of empathy for other people. Ideas excite me. Empathy grounds and centers me.

Ironically, it was a lack of empathy that nearly cost me the chance to join Microsoft as a young man some twenty years before. Looking back to my own interview process decades ago, I remember that after a full day of interviews with various engineering leaders who tested my fortitude and my intellectual chops, I met Richard Tait—an up-and-coming manager who went on to found Cranium games. Richard didn’t give me an engineering problem to solve on the whiteboard or a complex coding scenario to talk through. He didn’t grill me on my prior experiences or educational pedigree. He had one simple question.

“Imagine you see a baby laying in the street, and the baby is crying. What do you do?” he asked.

“You call 911,” I replied without much forethought.

Richard walked me out of his office, put his arm around me, and said, “You need some empathy, man. If a baby is laying on a street crying, pick up the baby.”

Somehow, I got the job anyway, but Richard’s words have remained with me to this day. Little did I know then that I would soon learn empathy in a deeply personal way.

It was just a few short years later that our first child, Zain, was born. My wife, Anu, and I are our parents’ only children, and so you can imagine there had been much anticipation of Zain’s birth. With help from her mom, Anu had been busily equipping the house for a new happy and healthy baby. Our preoccupations were more centered around how quickly Anu might return to her burgeoning career as an architect from maternity leave. Like any parent, we thought about how our weekends and vacations would change when we turned parents.

One night, during the thirty-sixth week of her pregnancy, Anu noticed that the baby was not moving as much as she was accustomed to. So we went to the emergency room of a local hospital in Bellevue. We thought it would be just a routine checkup, little more than new parent anxiety. In fact, I distinctly remember feeling annoyed by the wait times we experienced in the emergency room. But upon examination, the doctors were alarmed enough to order an emergency cesarean section. Zain was born at 11:29 p.m. on August 13, 1996, all of three pounds. He did not cry.

Zain was transported from the hospital in Bellevue across Lake Washington to Seattle Children’s Hospital with its state-of-the-art Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Anu began her recovery from the difficult birth. I spent the night with her in the hospital and immediately went to see Zain the next morning. Little did I know then how profoundly our lives would change. Over the course of the next couple of years we learned more about the damage caused by utero asphyxiation, and how Zain would require a wheelchair and be reliant on us because of severe cerebral palsy. I was devastated. But mostly I was sad for how things turned out for me and Anu. Thankfully, Anu helped me to understand that it was not about what happened to me. It was about deeply understanding what had happened to Zain, and developing empathy for his pain and his circumstances while accepting our responsibility as his parents.

Being a husband and a father has taken me on an emotional journey. It has helped me develop a deeper understanding of people of all abilities and of what love and human ingenuity can accomplish. As part of this journey I also discovered the teachings of India’s most famous son—Gautama Buddha. I am not particularly religious, but I was searching and I was curious why so few people in India have been followers of Buddha despite his origins. I discovered Buddha did not set out to found a world religion. He set out to understand why one suffers. I learned that only through living life’s ups and downs can you develop empathy; that in order not to suffer, or at least not to suffer so much, one must become comfortable with impermanence. I distinctly remember how much the “permanence” of Zain’s condition bothered me in the early years of his life. However, things are always changing. If you could understand impermanence deeply, you would develop more equanimity. You would not get too excited about either the ups or downs of life. And only then would you be ready to develop that deeper sense of empathy and compassion for everything around you. The computer scientist in me loved this compact instruction set for life.

Don’t get me wrong. I am anything but perfect and for sure not on the verge of achieving enlightenment or nirvana. It’s just that life’s experience has helped me build a growing sense of empathy for an ever-widening circle of people. I have empathy for people with disabilities. I have empathy for people trying to make a living from the inner cities and the Rust Belt to the developing countries of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. I have empathy for small business owners working to succeed. I have empathy for any person targeted with violence and hate because of the color of his or her skin, what they believe, or who they love. My passion is to put empathy at the center of everything I pursue—from the products we launch, to the new markets we enter, to the employees, customers, and partners we work with.

Of course, as a technologist, I have seen how computing can play a crucial role in improving lives. At home, Zain’s speech therapist worked with three high school students to build a Windows app for Zain to control his own music. Zain loves music and has wide-ranging tastes spanning eras, genres, and artists. He likes everything from Leonard Cohen to Abba to Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and wanted to be able to flip through these artists, filling his room with whatever music suited him at any given moment. The problem was he couldn’t control the music on his own—he always had to wait for help, which can be frustrating for him and us. Three high school students studying computer science heard of this problem and wanted to help. Now Zain has a sensor on the side of his wheelchair that he can easily tap his head against to flip through his music collection. What freedom and happiness the empathy of three teenagers has brought to my son.

That same empathy has inspired me at work. Back in our leadership team meeting, to wrap up my discussion, I shared the story of a project we had just completed at Microsoft. Empathy, coupled with new ideas, had helped to create eye-gaze tracking technology, a breakthrough natural user interface that assists people with ALS (also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease) and cerebral palsy to have more independence. The idea emerged from the company’s first-ever employee hackathon, a hotbed of creativity and dreams. One of the hackathon teams had developed empathy by spending time with Steve Gleason, a former NFL player whose ALS confines him to a wheelchair. Like my son, Steve now uses personal computing technology to improve his daily life. Believe me, I know what this technology will mean for Steve, for millions around the world, and for my son at home.

Our roles on the SLT started to change that day. Each leader was no longer solely employed by Microsoft, they had tapped into a higher calling—to employ Microsoft in pursuit of their personal passions to empower others. It was an emotional and exhausting day, but it set a new tone and put in motion a more unified leadership team. At the end of the day, we all came to the same stark realization: No one leader, no one group, and no one CEO would be the hero of Microsoft’s renewal. If there was to be a renewal, it would take all of us and all parts of each of us. Cultural transformation would be slow and trying before it would be rewarding.

* * *

This is a book about transformation—one that is taking place today inside me and inside of our company, driven by a sense of empathy and a desire to empower others. But most important, it’s about the change coming in every life as we witness the most transformative wave of technology yet—one that will include artificial intelligence, mixed reality, and quantum computing. It’s about how people, organizations, and societies can and must transform—hit refresh—in their persistent quest for new energy, new ideas, relevance, and renewal. At the core, it’s about us humans and the unique quality we call empathy, which will become ever more valuable in a world where the torrent of technology will disrupt the status quo like never before. The mystical Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke once wrote that “the future enters into us, in order to transform itself in us, long before it happens.” As much as elegant computer code for machines, existential poetry can illuminate and instruct us. Speaking to us from another century, Rilke is saying that what lies ahead is very much within us, determined by the course each of us takes today. That course, those decisions, is what I’ve set out to describe.

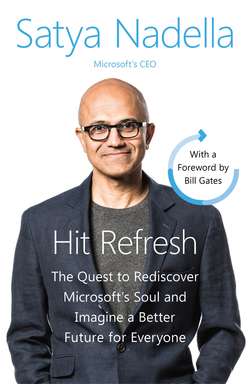

In these pages, you will follow three distinct storylines. First, as prologue, I’ll share my own transformation moving from India to my new home in America with stops in the heartland, in Silicon Valley, and at a Microsoft then in its ascendancy. Part two focuses on hitting refresh at Microsoft as the unlikely CEO who succeeded Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer. Microsoft’s transformation under my leadership is not complete, but I am proud of our progress. In the third and final act, I’ll take up the argument that a Fourth Industrial Revolution lies ahead, one in which machine intelligence will rival that of humans. We’ll explore some heady questions. What will the role of humans become? Will inequality resolve or worsen? How can governments help? What is the role of multinational corporations and their leaders? How will we hit refresh as a society?

I was excited to write this book, but also a little reluctant. Who really cares about my journey? With only a few years under my belt as Microsoft’s CEO, it felt premature to write about how we’ve succeeded or failed on my watch. We’ve made a lot of progress since that SLT meeting, but we still have a long way to go. That’s also why I’m not interested in writing a memoir. I’ll save that for my dotage. But several arguments convinced me to carve out a little time at this stage of my life to write. I felt the tug of responsibility to tell our story from my perspective. It’s also a time of enormous social and economic disruption accelerated by technological breakthroughs. The combination of cloud computing, sensors, Big Data, machine learning, and Artificial Intelligence (AI), mixed reality, and robotics foreshadows socioeconomic change ripped from the pages of science fiction. There is a wide and growing spectrum of debate about the implications of this coming wave of intelligent technologies. On the one hand, Pixar’s film WALL-E paints a portrait of eternal relaxation for humans who rely on robots for the hard work. But on the other, scientists like Stephen Hawking warn of doom.

The most compelling argument was to write for my colleagues—Microsoft’s employees—and for our millions of customers and partners. After all, on that cold February day in 2014 when Microsoft’s board of directors announced that I would become CEO, I put the company’s culture at the top of our agenda. I said that we needed to rediscover the soul of Microsoft, our reason for being. I have come to understand that my primary job is to curate our culture so that one hundred thousand inspired minds—Microsoft’s employees—can better shape our future. Books are so often written by leaders looking back on their tenures, not while they’re in the fog of war. What if we could share the journey together, the meditations of a sitting CEO in the midst of a massive transformation? Microsoft’s roots, its original raison d’être, was to democratize computing, to make it accessible to everyone. “A computer on every desk and in every home” was our original mission. It defined our culture. But much has changed. Most every desk and home now have a computer, and most people have a smartphone. We had succeeded in many ways, but we also were lagging in too many other ways. PC sales had slowed and we were significantly behind in mobile. We were behind in search and we needed to grow again in gaming. We needed to build deeper empathy for our customers and their unarticulated and unmet needs. It was time to hit refresh.

After twenty-two years as an engineer and a leader at Microsoft, I had been more philosophical than anxious about the search process for a new CEO. Even with speculation swirling about who would succeed Steve, quite frankly, my wife, Anu, and I largely ignored the rumors. At home, we were just too busy with taking care of Zain and our two daughters. At work I was very focused on continuing to grow a highly competitive business, the Microsoft Cloud. My attitude was that the board would select the best person. It would be great if it were me. But I would also be equally happy working for someone the board had confidence in. In fact, as part of the interview process one of the board members suggested that if I wanted to be CEO, I needed to be clear that I was hungry for the job. I thought about this and even talked to Steve. He laughed and simply said, “It’s too late to be different.” It just wouldn’t be me to display that kind of personal ambition.

When John Thompson, who at that time was the lead independent director and headed the CEO search, sent me an email on January 24, 2014, asking for time to chat, I was not sure what to make of it. I thought he probably was going to give me an update on where the board was in its decision process. And so, when John called that evening, he first asked me if I was sitting down. I was not. In fact, I was calmly playing with a Kookaburra cricket ball as I usually do when talking on the speakerphone at work. He went on to deliver the news that I was to become the new CEO of Microsoft. It took a couple of minutes to digest his message. I said that I was honored, humbled, and excited. They were unplanned words, but they perfectly captured how I felt. Weeks later, I told media outlets that we needed to focus more clearly, move faster, and continue to transform our culture and business. But behind the scenes, I knew that to lead effectively I needed to get some things square in my own mind—and, ultimately, in the minds of everyone who works at Microsoft. Why does Microsoft exist? And why do I exist in this new role? These are questions everyone in every organization should ask themselves. I worried that failing to ask these questions, and truly answer them, risked perpetuating earlier mistakes and, worse, not being honest. Every person, organization, and even society reaches a point at which they owe it to themselves to hit refresh—to reenergize, renew, reframe, and rethink their purpose. If only it were as easy as punching that little refresh button on your browser. Sure, in this age of continuous updates and always-on technologies, hitting refresh may sound quaint, but still when it’s done right, when people and cultures re-create and refresh, a renaissance can be the result. Sports franchises do it. Apple did it. Detroit is doing it. One day ascending companies like Facebook will stop growing, and they will have to do it too.

And so let me start at the beginning—my own story. I mean, what kind of CEO asks such existential questions as why do we exist in the first place? Why are concepts like culture, ideas, and empathy so important to me? Well, my father was a civil servant with Marxist leanings and my mother was a Sanskrit scholar. While there is much I learned from my father, including intellectual curiosity and a love of history, I was always my mother’s son. She cared deeply about my being happy, confident, and living in the moment without regrets. She worked hard both at home and in the college classroom where she taught the ancient language, literature, and philosophy of India. And she created a home full of joy.

Even so, my earliest memories are of my mom struggling to continue her profession and to make the marriage work. She was the constant, steadying force in my life, and my father was larger than life. He nearly immigrated to the United States, a faraway place that represented opportunity, on a Fulbright fellowship to pursue a PhD in economics. But those plans were suddenly and understandably shelved when he was selected to join the Indian Administrative Service (IAS). It was early 1960s, and Jawaharlal Nehru was India’s first prime minister following Gandhi’s historic movement, which had achieved independence from Great Britain. For that generation entering the civil service and being part of the birth of a new nation was a true dream come true. The IAS was essentially a remnant of the old Raj system left by the British to govern after the UK turned over control of the country in 1947. Only about a hundred young professionals per year were selected for the IAS, and so at a very young age my father was administering a district with millions of people. Throughout my childhood, he was posted in many districts across the state of Andhra Pradesh in India. I remember moving from place to place, growing up in the sixties and early seventies in old colonial buildings in the middle of nowhere with lots of time and space, and in a country being transformed.

My mom did her level best during all these disruptions to maintain her teaching career, raise me, and be a loving wife. When I was about six, my five-month-old sister died. It had a huge impact on me and our family. Mom had to give up working after that. I think my sister’s death was the last straw. Losing her, combined with raising me and working to maintain a career while my father was working in faraway places was just too much. She never complained to me at all about it, but I reflect on her story quite a bit, especially in the context of today’s diversity conversations across the technology industry. Like anyone, she wanted to, and deserved to, have it all. But the culture of her workplace, coupled with the social norms of Indian society at the time, didn’t make it possible for her to balance family life with her professional passions.

Among the children of IAS fathers, it was a rat race. For some of the IAS dads, simply passing the grueling entrance test meant they were set for life. It was the last test they would ever have to take. But my father believed passing the IAS exam was merely the entry point to being able to take even more important exams. He was a quintessential lifelong learner. But unlike most of my peers at that time, whose high-achieving parents applied tremendous pressure to achieve, I didn’t face any of that. My mom was just the opposite of a tiger mom. She never pressured me to do anything other than just be happy.

That suited me just fine. As a kid, I couldn’t have cared less about pretty much anything, except for the sport of cricket. One time, my father hung a poster of Karl Marx in my bedroom; in response, my mother hung one of Lakshmi, the Indian goddess of plentitude and contentment. Their contrasting messages were clear: My father wanted intellectual ambition for me, while my mother wanted me to be happy versus being captive to any dogma. My reaction? The only poster I really wanted was one of my cricketing hero, the Hyderabadi great, M. L. Jaisimha, famous for his boyish good looks and graceful style, on and off the field.

Looking back, I have been influenced by both my father’s enthusiasm for intellectual engagement and my mother’s dream of a balanced life for me. And even today, cricket remains my passion. Nowhere is the intensity for cricket greater than in India, even if the game was invented in England. I was good enough to play for my school in Hyderabad, a place that had a lot of cricket tradition and zeal. I was an off-spin bowler, which in baseball would be the equivalent to a pitcher with a sharp breaking curveball. Cricket attracts an estimated 2.5 billion fans globally, compared with just half a billion baseball fans. Both are beautiful sports with passionate fans and a body of literature brimming with the grace, excitement, and complexities of competition. In his novel, Netherland, Joseph O’Neill describes the beauty of the game, its eleven players converging in unison toward the batsman and then returning again and again to their starting point, “a repetition or pulmonary rhythm, as if the field breathed through its luminous visitors.” I think of that metaphor of the cricket team now as a CEO when reflecting on the culture we need in order to be successful.

I had attended schools in many parts of India—Srikakulam, Tirupati, Mussoorie, Delhi, and Hyderabad. Each left its mark and has remained with me. Mussoorie, for example, is a northern Indian city tucked into the foothills of the Himalayas, around six thousand feet of elevation. Every time I see Mount Rainier from my home in Bellevue, I am always reminded of the mountains of childhood—Nanda Devi and Bandarpunch. I attended kindergarten at the Convent of Jesus and Mary. It is the oldest school for girls in India but they let boys attend kindergarten. By age fifteen, we had stopped moving and I entered Hyderabad Public School, which boarded students from all over India. I’m thankful for all the moves—they helped me adjust quickly to new situations—but going to Hyderabad was truly formative. In the 1970s, Hyderabad was out of the way, not at all the metropolis of 6.8 million people it is today. I really didn’t know or care about the world west of Bombay on the Arabian Sea, but attending boarding school at HPS was the best break I had in my life.

At HPS I belonged to the Nalanda, or blues house, which was named for an ancient Buddhist university. The whole school was multicultural: Muslims, Hindus, Christians, Sikhs all living and studying together. The school was attended by members of the elite as well as by tribal kids who had come from the interior districts on scholarships. The chief minister’s son attended HPS alongside the children of Bollywood actors. In my dorm there were kids from every part of the Indian economic strata. It was an amazingly equalizing force—a moment in time worth remembering.

The list of alumni today speaks to this success. Shantanu Narayen, the CEO of Adobe; Ajay Singh Banga, the CEO of MasterCard; Syed B. Ali, head of Cavium Networks; Prem Watsa, founder of Fairfax Financial Holdings in Toronto; parliament leaders, film stars, athletes, academics, and writers—all came from this small, out-of-the-way school. I was not academically great and nor was the school known to push academics. If you liked to study physics, you studied physics. If you felt like, oh, science was too boring and you wanted to study history, you studied history. There wasn’t that intense peer pressure to follow a particular path.

After a few years at HPS my dad went to work at the United Nations in Bangkok. He wasn’t too fond of my laid-back attitude. He said, “I’m going to pull you out and you should come do your eleventh and twelfth in some international school in Bangkok.” I said no chance. And so I just stuck to Hyderabad. Everybody was thinking, “Are you crazy, why would you do that?” But there was no way I was leaving. Cricket was a major part of my life at that time. Attending that school gave me some of my greatest memories, and a lot of confidence.

By twelfth grade if you had asked me about my dream it was to attend a small college, play cricket for Hyderabad, and eventually work for a bank. That was it. Being an engineer and going to the West never occurred to me. My mom was happy with those plans. “That’s fantastic, son!” But my dad really forced the issue. He said, “Look, you’ve got to get out of Hyderabad. Otherwise you’ll ruin yourself.” It was good advice then, but few could predict that Hyderabad would become the technological hub it is today. It was hard to break from my circle of friends, but Dad was right. I was being provincial with my ambitions. I needed some perspective. Cricket was my passion, but computers were a close second. When I was fifteen, my father brought me a Sinclair ZX Spectrum computer kit from Bangkok. Its Z80 CPU had been developed in the mid-seventies by an engineer who left Intel, where he had been working on the 8080 microprocessor, which ironically was the chip Bill Gates and Paul Allen used to write the original version of Microsoft BASIC. The ZX Spectrum inspired me to think about software, engineering, and even the idea that personal computing technologies could be democratizing. If a kid in nowhere India could learn to program, surely anyone could.

I flunked the Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) entrance exam, the holy grail of all things academic for middle-class kids growing up in India at that time. My father, who never met an entrance test he did not pass, was more amused than annoyed. But, luckily, I had two other options to pursue engineering. I had gotten into mechanical engineering at Birla Institute of Technology in Mesra and electrical engineering (EE) at Manipal Institute of Technology. I chose Manipal based on a hunch that pursuing EE was going to get me closer to computers and software. And fortuitously the hunch was right. Academically it put me on a pathway that would lead to Silicon Valley and eventually to Microsoft. The friends I made in college were entrepreneurial, driven, and ambitious. I learned from many of them. In fact, years later I rented a house in Sunnyvale, California, with eight of my classmates from Manipal and re-created our dorm-room experience from college. Athletically, though, Manipal left a lot to be desired. Playing cricket was no longer my central passion. I played one match for my college team and hung up my gear. Computers took cricket’s place and became number one in my life. At Manipal I trained in microelectronics—integrated circuits and the first principles of making computers.

I didn’t really have a specific plan for what I’d do after finishing my electrical engineering degree. There is much to be said for my mother’s philosophy of life, which influenced how I thought about my own future and opportunities. She always believed in doing your thing, and at your pace. Pace comes when you do your thing. So long as you enjoy it, do it mindfully and well, and have an honest purpose behind it, life won’t fail you. That has stood me in good stead all my life. After graduation, I had an opportunity to attend a prestigious industrial engineering institute in Bombay. I had also applied to a few colleges in the United States. In those days, the student visa was bit of a crapshoot, and frankly I was hoping it would be rejected. I never wanted to leave India. But as fate would have it, I got my visa and was again faced with some choices—whether to stay in India and do a master’s degree in industrial engineering or go to the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee for a master’s degree in electrical engineering. A very dear friend from HPS was attending Wisconsin studying computer science, and so my decision was made. I entered the master’s in computer science program at Wisconsin. And I’m glad I did because it was a small department with professors who were invested in their students. I’m particularly thankful to then department chair Dr. Vairavan and my master’s advisor Professor Hosseini for instilling in me the confidence not to pursue what was easy, but to tackle the biggest and hardest problems in computer science.

If someone had asked me to point to Milwaukee on a map I could not have done it. But on my twenty-first birthday, in 1988, I flew from New Delhi to Chicago O’Hare Airport. From there a friend drove me to campus and dropped me off. What I remember was the quiet. Everything was quiet. Milwaukee was just stunning, pristine. I thought, god, this place is heaven on earth. It was summer. It was beautiful, and my life in the United States was just beginning.

Summer became winter and the cold of Wisconsin is something to behold if you’ve come from southern India. I was a smoker at the time and all smokers had to stand outside. There were a number of us from various parts of the world. The Indian students couldn’t stand the cold so we quit smoking. Then my Chinese friends quit. But the Russians were unaffected by winter’s chill, and they just kept on puffing away.

Sure, I would get homesick, like any kid, but America could not have been more welcoming. I don’t think my story would be possible anywhere else, and I am proud today to call myself an American citizen. Looking back, though, I suppose my story may sound a little programmatic. The son of an Indian civil servant studies hard, gets an engineering degree, immigrates to the United States, and makes it in tech. But it wasn’t that simple. Unlike the stereotype, I was actually not academically that great. I didn’t go to the elite Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) that have become synonymous with building Silicon Valley. Only in America would someone like me get the chance to prove himself rather than be typecast based on the school I attended. I suppose that was true for earlier waves of immigration as well and will be just as true for new generations of immigrants.

Like many others, it was my great fortune to benefit from the convergence of several tectonic movements: India’s independence from British rule, the American civil rights movement, which changed immigration policy in the United States, and the global tech boom. Indian independence led to large investments in education for Indian citizens like me. In the United States, the 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act abolished the nation-of-origin quota and made it possible for skilled workers to come to America and contribute. Before that, only about a hundred Indians were allowed to immigrate each year. Writing for The New York Times on the fiftieth anniversary of the immigration act, historian Ted Widmer noted that nearly 59 million people came to the United States as a result of the act. But the influx was not unrestrained. The act created preferences for those with technical training and those with family members already in the States. Unknowingly, I was the recipient of this great gift. These movements enabled me to show up in the United States with software skills just before the tech boom of the 1990s. Talk about hitting the lottery.

During the first semester at Wisconsin, I took image processing, a computer architecture class, and LISP, one of the oldest computer programming languages. The first set of assignments were just huge programming projects. I’d written a little bit of code but I was not a proficient coder by any stretch. I know the stereotype in America is that the Indians who immigrate are born to code, but we all start somewhere. The assignments were, basically, here it is, go write a bunch of code. It was tough and I had to pick it up quickly. Once I did, it was awesome. I understood pretty early on that the microcomputer was going to shape the world. Initially I thought it might be all about building chips. Most of my college friends all went on to specialize in chip design and work at places with real impact like Mentor Graphics, Synopsys, and Juniper.

I became particularly interested in a theoretical aspect of computer science that was, at its heart, designed to make fast decisions in an atmosphere of great uncertainty and finite time. My focus was a computer science puzzle known as graph coloring. No, I wasn’t coloring graphs with crayons. Graph coloring is part of computational complexity theory in which you must assign labels, traditionally called colors, to elements of a graph within certain constraints. Think of it this way: Imagine coloring the U.S. map so that no state sharing a common border receives the same color. What is the minimal number of colors you would need to accomplish this task? My master’s thesis was about developing the best heuristics to accomplish complex graph coloring in nondeterministic polynomial time, or NP-complete. In other words, how can I solve a problem that has limitless possibilities in a way that is fast and good but not always optimal? Do we solve this as best we can right now, or work forever for the best solution?

Theoretical computer science really grabbed me because it showed the limits to what today’s computers can do. It led me to become fascinated by mathematicians and computer scientists John Von Neumann and Alan Turing, and by quantum computing, which I will write about later as we look ahead to artificial intelligence and machine learning. And, if you think about it, this was great training for a CEO—nimbly managing within constraints.

I completed my master’s in computer science at Wisconsin and even managed to work for what Microsoft would now call an independent software vendor (ISV). I was building apps for Oracle databases while finishing my master’s thesis. I was good at relational algebra and became proficient with databases and structured query language (SQL) programming. This was the era where technology was changing from character or text mode on UNIX workstations to graphical user interfaces like Windows. It was early 1990 and I didn’t even really think about Microsoft at that time because we never used PCs. My focus was on more powerful workstations.

In fact, I left Milwaukee in 1990 for my first job in Silicon Valley at Sun Microsystems. Sun was the king of workstations, a market Microsoft had in its crosshairs. Sun had an amazing collection of talent, including its founders Scott McNealy and Bill Joy, as well as James Gosling, the inventor of Java, and Eric Schmidt, our VP for software development who went on to run Novell and then Google.

My two years at Sun were a time of great transition in the computer business as Sun looked longingly at Microsoft’s Windows graphical user interface, and Microsoft looked longingly at Sun’s beautiful, powerful 32-bit workstations and operating systems. Again, I happened to be at the right place at the right time. Sun asked me to work on desktop software like their email tool. I was later sent to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to work for several months with Lotus to port their spreadsheet software to Sun workstations. Then I started to notice something alarming. Every couple of months, Sun wanted to adopt a new graphical user interface (GUI) strategy. That meant I had to rework my programs constantly, and their explanations made less and less sense. I realized that despite its phenomenal leadership and capability, it had a hard time building and sticking with a cogent software strategy.

By 1992, I was again at a crossroads in my life. I wanted to work on software that would change the world. I also wanted to return to graduate school for my MBA. And I missed Anu, whom I intended to marry and bring to the United States. She was finishing her degree in architecture back in Manipal, and we began to plan for her to join me in America.

Like all the times before, there was no master plan, but a call from Redmond, Washington, one afternoon would create a new, unexpected opportunity. It was time to hit refresh again.

* * *

On a cool, November day in the Pacific Northwest, I first set foot on the Microsoft campus and entered an unremarkable corporate office unimaginatively named Building 22. Shrouded by towering Douglas firs, it remains even today barely visible from the adjacent state route 520, known for its floating bridge connecting Seattle to Redmond. The year was 1992. Microsoft’s stock was just beginning an epic rise, though its founders, Bill Gates and Paul Allen, could still walk down the street unrecognized. Windows 3.1 had just been released, setting the stage for Windows 95 and the grandest consumer technology product launch yet. Sony introduced the CD-ROM, and the first website was launched, though it would be two more years before the Internet would become a tidal wave. TCI introduced digital cable and the FCC approved digital radio. On a chart, PC sales at this time show the start of a meteoric ascent. Looking back now, I couldn’t have timed my entrance any better. The resources, the talent and the vision were there to compete and to lead the industry. My journey to Redmond had taken me from my home in India to Wisconsin for graduate school to the Silicon Valley to work for Sun. Over the summer I had been recruited to join Microsoft as a twenty-five-year-old evangelist for Windows NT, a 32-bit operating system that was designed to extend the company’s popular consumer program into much more powerful business systems. A few years later NT would become the backbone of future Windows versions. Even today’s generation of Windows, Windows 10, builds on the original NT architecture. I had heard of NT while working at Sun but had never used it. A colleague had attended a Microsoft conference where they showed off NT to developers. He came back and told me about the product. I thought, wow, this is going to get serious. I wanted to be in a place that would have real impact. The guys who had recruited me to Microsoft, Richard Tait and Jeff Teper, said they needed someone who understood UNIX and 32-bit operating systems. I was a little unsure. What I really wanted to do was go to business school. I knew that management would complement my engineering training, and I had been thinking about a switch to investment banking. I had gotten into the full-time program at University of Chicago, but Teper said, “You should just join us straightaway.” I decided to do both. I was able to switch my admission to the part-time program at Chicago, but then never told anyone that I was flying to Chicago for weekends. I finished my MBA in two years and was glad I did. During the week my job was to fly all over the country—lugging these enormous Compaq computers—to meet with customers, usually chief information officers at places like Georgia Pacific or Mobil, to convince them that our new, more robust operating system for business was superior to the others and convert them. And at school I learned more math by taking high-level finance classes in Chicago than in my engineering coursework. The classes I took with Steven Kaplan, Marvin Zonis, and many other storied faculty at the university on strategy, finance, and leadership influenced my thinking and intellectual pursuits long after I completed the MBA. It was an exciting time to be at Microsoft. Not long after joining I met Steve Ballmer for the first time. He stopped by my office to give me one of his very expressive high fives for leaving Sun and joining Microsoft. It was the first of what would be many interesting and enjoyable conversations with Steve over the years. There was a true sense of mission and energy at the company then. The sky was the limit.

* * *

Within a few years my work on Windows NT landed me in a new advanced technology group, founded by Renaissance man Nathan Myhrvold. Along with Rick Rashid, Craig Mundie, and others, Microsoft was assembling the greatest technology IQ since Xerox PARC, the famed Silicon Valley center for innovation. I was humbled when asked to join the group as a product manager on a project code-named Tiger Server, which was a major investment in building a video-on-demand (VOD) service. It would be years before cable companies would deliver the technology and business model to support VOD, and years before Netflix made video streaming mainstream. Fortunately, I lived right next to the Microsoft campus, the endpoint for all of this amazing broadband infrastructure that made our VOD pilot possible. So in 1994, long before it was commercially available, I had video-on-demand while sitting in my little apartment. We only had about fifteen movies but I remember watching them over and over again. Even as our team planned to launch our Tiger server over a fully switched asynchronous transfer mode (ATM) network to the home, we saw our idea become obsolete virtually overnight with the birth of the Internet.

* * *

While my mind was fully engaged, my heart was distracted. Anu and I had decided to marry when I made a trip back to India just before joining Microsoft. I had known Anu all of my life. Her dad and my father had joined the IAS together and we were family friends. In fact, Anu’s dad and I shared a passion for talking endlessly about cricket, something we continue to this day. He had played for his school and college, captaining both teams. When exactly I fell in love with Anu is what computer scientists would call an NP complete question. I can come up with many times and places but there is no one answer. In other words, it’s complex. Our families were close. Our social circles were the same. As kids we had played together. We overlapped in school and college. Our beloved family dog came from Anu’s family dog’s litter. But once I moved to the United States, I lost touch with her. When I went back to India for a visit, we saw each other again. She was in her final year of architecture at Manipal and enjoying an internship in New Delhi. Our two families met for dinner one evening, and that night, more than ever, I was convinced that she was the one. We shared the same values, the same outlook on the world, and dreamed of similar futures. In many ways, her family was already mine and mine hers. The next day, I persuaded her to take me to an optician where I needed to have my glasses repaired. After the appointment, we walked and talked for hours in the neighboring Lodi Gardens, an ancient architectural site that today is popular with tourists. Anu, a student of architecture, loved all the historical monuments that dotted Delhi, and for days afterward we explored them together. I had visited them all before as a kid. But this was different. We stopped for lunch on Pandara Road, enjoyed plays in the National Institute of Drama, and shopped in the bookstores of Khan Market. We had fallen in love. It was in the lush Lodi Gardens that one October afternoon in 1992 I proposed and, thankfully for me, Anu said yes. We walked back to Anu’s place on Humayun Road and broke the news to Anu’s mom. We were married just two months later, in December. It was a happy time, but the complications of immigration would soon prove a challenge.

* * *

Anu was in the last year of her architecture degree and the plan was for her to complete the remaining course and join me in Redmond. In the summer of 1993, Anu applied for a visa to join me during her final vacation before finishing school. But her visa application was rejected because she was married to a permanent resident. Anu’s father sought an appointment with the U.S. consul general in New Delhi and argued with him that the U.S. visa rules were not consistent with the family values that the United States stood for. The combination of his persuasiveness and the kindness of the U.S. consul general led to Anu getting a short-term tourist visa—a rare exception. After her vacation, she returned to India and college to complete her degree. It was now clear to us that Anu’s return to the United States would be very difficult given the visa waitlist for spouses of permanent residents. Microsoft had an immigration lawyer who told me it would take five or more years to get Anu into the country under existing rules. I contemplated quitting Microsoft and returning to India. But our lawyer, Ira Rubinstein, said something interesting. “Hey, maybe you should give up your green card and go back to an H1B.” He was suggesting that I give up permanent residency and instead reapply for temporary professional worker status. If you’ve seen the Gerard Depardieu film Green Card, you know the comedic lengths people will go to to obtain permanent residency in the United States. So why would I give up the coveted green card for temporary status? Well, the H1B enables spouses to come to the United States while their husbands and wives are working here. Such is the perverse logic of this immigration law. There was nothing I could do about it. Anu was my priority. And that made my decision a simple one. I went back to the U.S. embassy in Delhi in June of 1994, past the enormous lines of people hoping to get a visa, and told a clerk that I wanted to give back my green card and apply for an H1B. He was dumbfounded. “Why?” he asked. I said something about the crazy immigration policy, he shook his head and pushed a new form to me. “Fill this out.” The next morning, I returned to apply for an H1B application. Miraculously, it all worked. Anu joined me (for good) in Seattle, where we would start a family and build a life together. What I didn’t expect was the instant notoriety around campus. “Hey, there goes the guy who gave up his green card.” Every other day someone would call me and ask for advice. Much later, one of my colleagues, Kunal Bahl, did quit Microsoft when his H1B ran out and his green card had not yet arrived. He returned to India and then founded Snapdeal, which today is worth more than $1 billion and employs five thousand people. Ironically, online, cloud-based companies like Snapdeal would play an important role in my future and that of Microsoft. And the lessons I learned in my former country continue to shape my present.