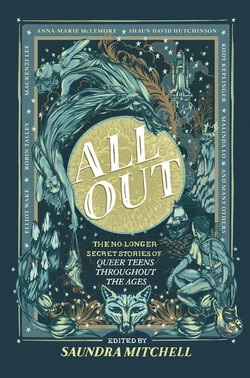

Читать книгу All Out: The No-Longer-Secret Stories Of Queer Teens Throughout The Ages - Saundra Mitchell - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEl Bajío, México , 1870

They all gave him different names. The authorities, who had been trying for months to catch him, called him El Lobo. The Wolf. La Légion called him Le Loup.

His mother, back in Alsace, had christened him with a girl’s name, though he had since forgiven her for that. It was a name he had trusted me with but that I knew never to speak. The sound of it was too much a reminder of when he’d been too young to fight the hands trying to turn him into a proper demoiselle, forbidding him from running outside because young ladies should not do that. His heart had been a boy’s heart, throwing itself against his rib cage with each set of white gloves for mass.

I called him his true name, Léon, the one he’d chosen himself. None of this was strange to me, a boy deciding his own name. The only strange thing was the fact that he knew mine.

No one outside our village called me or anyone else in my family by our real names. They worried that letting our names onto their tongues would leave them sick. The rumors said our hearts were dangerous as a coral snake’s bite. They carried the whisper that the women in my family could murder with nothing but our rage. They pointed to our hair, red as our skin was brown, and insisted el Diablo himself had dyed it with the juice of devil’s berries, to mark us as his.

Abuela had told me our rage was a thing we must tame. Though everyone else feared that our rage might kill them, the lives it more often took were ours. Poison slipped from our hearts and into our blood, she said. The venom spread to our fingers and the ends of our hair.

But even she found a little joy in it. She flaunted it. So we would have enough to eat, she taught me to crush red dye from the beetles that infested the nopales. They were pests, ravaging the cactus pads, but if caught they made a stain so deep red we could sell it. My grandmother even tied tiny woven baskets to the nopales, luring the insects to make nests.

That only added to the rumors. Las Rojas, the grandmother and granddaughter whose hearts blazed so red it showed in their hair, and who made the same color and sold it with stained fingertips. We heard whispers as we passed churches, families drawing back from us, afraid we could kill them with a glare.

Now, as I stood in front of Deputy Oropeza’s polished desk, I wished all the stories were true.

“You want El Lobo released?” Oropeza rested his boots on the smooth-finished wood.

The toes of his boots, long and pointed as a snake’s tongue, narrowed and curved up toward his shins. They had become the fashion of rich men, who now wore them not only for celebrations but in the streets, the forks nipping at anyone who got in their way.

“Tell me you’ve come here as a joke,” he said. “Tell me one of my friends sent you to see if I would be taken in. Was it Calvo?”

His hand flashed through the air. I flinched, thinking he might strike me. But he was halting me from speaking.

“No, don’t tell me,” he said. “It was Acevedo, wasn’t it?” He clapped his hands. “I swear on the gospel, that man stops breathing if he isn’t trying to trick someone.”

If Oropeza attended church, if he worshipped anyone but himself, he’d know better than to swear on la Biblia. But I kept silent.

“How much did he pay you to do this?” Oropeza’s boots thudded on the tile floor. “Because I’ll double it if you help me play my own little trick on him.”

The rage in me shuddered and trembled. It felt like it was flickering off my eyelashes.

“No one sent me,” I said.

The richest men in El Bajío couldn’t have paid me to be here. But I had begged every official who would see me.

Most I found by stopping them in the street. The ones who listened bowed their heads to tell me there was nothing they could do, not for any Frenchman, least of all El Lobo.

The ones who didn’t want to hear me—Senator Ariel, Governor Quintanar—shoved me to make me move. They backed away from me like I was crafted out of mud, as though if they came too close I might dirty them.

I was not a girl who could ask for things. I was not powder and perfume and lace-trimmed fans. The kind of women who could wheedle favors from wealthy men wore dresses in the purples and deep pinks of cactus fruit. They wore silk and velvet ribbons tied as necklaces. The owners of blue agave farms sent them sapphire and emerald rings.

They were not girls in plain huipils.

But Deputy Oropeza had agreed to see me. Hope had bloomed in the dark space beneath my heart. Yes, he wore the pointed boots of rich men, but he hadn’t gotten into the same competitions the others had, driving one another to have boots made with toes as long as I was tall. Maybe there was reason in him.

“Please,” I said now.

The war had ended. But the hills still lay scorched and barren, and Léon had been captured as an enemy Frenchman. Un francés. And now a blindfold and a bullet waited for him at dusk.

“He didn’t even want to fight with them,” I said. “He deserted.”

The things Léon had seen had driven him to betray his own country. I hated la Légion for what they had done to Léon. He hated them for letting their soldiers loose on this land. They raided villages, throwing women down on the earth floors of their homes, killing the men and keeping locks of their hair as trophies.

And those were only the things he had been willing to tell me, as though I myself had not known families killed or scarred by the French uniform. But he didn’t see the brown of my skin and consider me less than he was. He did not see the red of my hair and decide I was wicked. He saw me as something soft, a girl he did not want to plague with nightmares.

By the time Léon deserted, he had grown to hate not only la Légion but his own country, for starting this war in the name of unsettled debts, and for doing it while los Estados Unidos were too deep in their own civil war to intervene. So Léon had done the small but devastating things that earned him the name Le Loup. At night, he strolled into French camps wearing his stolen uniform. The blue coat with gold-fringed epaulettes. The red pants that tapered to cuffs at the ankles. The stiff yellow collar that rubbed against his neck when he nodded at the watchmen as though he belonged there.

He stole guns, throwing them into rivers. He set horses loose, driving them toward villages too poor to buy them. He pilfered maps and parchments, leaving them burning for the men to find. The rumors said he’d even called wolves from the hills, scattering the camps. But when I’d asked him about that, he only smiled.

Now the memory of Léon’s smile stung so hard I looked for the cut of it on my skin.

“He was working against them,” I told Oropeza.

Oropeza looked out through the silk curtains and onto the rows of curling grapevines.

“Then he is a traitor,” Oropeza said. “He is not even loyal to his own country. What would make you think he would be loyal to you?”

He turned his gaze to the square of tile where I stood in my huipil. In that moment, I saw myself as Oropeza must have seen me.

Men like Oropeza would never consider me worth looking at. I was short, wide hipped, a girl from the villages. I had only ever been told I was pretty by my abuela.

And Léon. My lobo.

Oropeza laughed. “The little campesina thinks el francés loves her?”

Campesina. I knew what that word meant to him, how he wielded it as both insult and fact. It was a word men like Oropeza kept ready on their tongues, a way to show their judgment both of where I had come from and the shape of my body. To them, my height and form marked me. A peasant’s shape, men like Oropeza called it, a shape made for work close to the ground.

“All he told you was lies,” Oropeza said. “He might have thought you were a little bit interesting.” He gestured at my hair. “A distraction.”

The salt of my own tears stung.

“One day you will thank me for what I’ve saved you from,” Oropeza said.

I set my back teeth together. He considered me and everyone like me a child. Men like him thought they had more of God in their hearts than we did, as though they held it in the lightness of their skin, or, for a few of them, in their eyes as blue as the seas their ancestors had crossed to claim this land.

Oropeza lurched forward, clutching his chest as though it had cramped. And then his stomach, as though he’d had a portion of bad wine.

I stepped back.

The venom in me, carried in my family’s blood, was spilling out. It had built in me, spun and strengthened by my rage. Then it had flowed into the air between me and Oropeza until he was sick with it.

This was the poison of Las Rojas, the venom our rage could become.

I kept myself back, pressing my tongue behind my teeth to stop myself.

I could not let the poison in my blood make Oropeza sick. If he’d heard the stories about my family and realized they were more truth than superstition, he would have me dragged into the street and killed as a bruja.

One of Oropeza’s men showed me out. My steps led me over the polished tile, and then out into Oropeza’s front gardens.

Léon had stayed for me. He had kept himself here, caught between la Légion he’d deserted and this country that considered him an enemy. And he’d been taken for it.

He’d never had the stomach for la Légion. He’d told me the night I found him, once I’d given him enough water for him to speak and he’d come out of the fever enough to make sense with his words.

He’d only joined because it had given him a way out of Alsace. He’d been told that la Légion would never check on the name he’d been born with, the name that would give away more than he ever wanted anyone to know of the body he kept beneath his clothes. The chest he bound down. The shoulders and back he worked hard enough that they could take as much weight as any other man’s.

And la Légion hadn’t checked. They did not want to know. They preferred their légionnaires forget who they’d been.

He could take the fighting, and even the beatings they gave les légionnaires to harden their spirits. But he could not stand how his régiment let the men work out their rage on village women. How they killed brothers or husbands who protested.

Léon had spoken up enough that they considered it rebellion. So each night they beat him in a way they called les couleurs. Blood on one cheek, bruises on the other, the pale, untouched stripe of his nose and lips between. The colors of the French flag, meant to put the allegiance back in him.

The night I found Léon, he’d worn those colors. It was the first time he’d tried running, and they’d caught him. So they’d tied him to one of the acacia trees that bloomed yellow each spring. His back against the thin trunk. His wrists and ankles bound behind it so he could not stand. All he could do was kneel.

They had told him that they may or may not come back for him, and if they did, it would be because they were curious if the wolves had eaten him.

That night, una vieja from our village had sent me into the woods. She asked me to bring her an oyamel branch from the fir tree she always held a little of as she prayed. I only noticed Léon because, at the sound of brush crackling under my feet, he lifted his head. His forehead shone with sweat. And through his fever, the thing I would later come to know as his charm seemed a kind of delirium, a madness. He’d mumbled a few words in French before saying, “If I’d known a beautiful woman would be calling on me, I would have made myself presentable.”

I unbound him and brought him home not because I was kind. I brought him home, holding him up as his eyes opened and shut, because if it had not been for the mercy of the other families in our village, my abuela would not have had a proper burial. I could not have done it myself. My heart was so weighted with losing her I was sure it would pull me into whatever hollow in the ground I made for her.

So I brought home this tall, underfed boy with hair so blond the moon made it look white. I boiled water and made pozole, to show God I was grateful, and that there was mercy left in me.

But there was no mercy in men like Oropeza, and Ariel, and Quintanar.

I had failed Léon. I had lost him. And now, at dusk, when a shot rang through the air, I screamed into the sound.

I screamed into the wind bringing me the rattling laugh of the men who killed Léon. I sobbed into the silhouettes of mesquite and acacia, and into the darkening blue of the sky.

Still screaming, I crossed myself, saying a prayer for the soul of Léon Bellamy.

Léon, the boy who made me laugh when he tripped over rolling his r’s. Léon, who had startled the village with his eyes, so pale gray that at night they looked silver, and his hair, light as bleached linen. Léon, who had won them over with his wonder about armadillos, how the animal rolled itself into a ball of plate armor.

Léon, the boy who had put his mouth to my ear and told me the brown of my skin made him think of wild deer roaming the woods where he was born.

Even in this moment, opening under me like a break in the earth, Abuela would have told me to find some small thing to thank God for. There was one, just one, I could get my fingers around.

No one, not la Légion, not Oropeza, ever knew Léon as anything but a boy. They did not know that his mother had christened him with a girl’s name. They did not know that he had joined la Légion less out of patriotism and more for the chance to live as who he was. If they had, Oropeza would have thrown it at me, mocked me for it. He would have made clear what he thought of us, Léon living among the other soldiers with his bound-down chest, me lifting my chin in the street as though I were the equal of the powder-pale women in their escaramuza dresses.

But even this small mercy broke in me. All of it broke.

First I had lost my grandmother, made sick from her rage over what this war had taken. She always warned me not to let my rage kill me, but in the end her own had spread its venom through her.

They said this war was over, even as women wept over their stoves and into their sewing. Even now when an Alsatian boy had just been blindfolded and shot.

My rage felt so hot it would singe away my smallest veins. There were so many empty places where everything I had lost once fit. Now there were only the dustless, unfaded patches where all I loved had been.

There was nothing left. Yes, there were the women who had loved me and my abuela; my abuela had fed them when they were sick and prayed over them when they bore children. There were even the ones who had taken to Léon like he was a stray. But now they only reminded me of those empty places.

I found the few clothes of my grandfather’s that Abuela had kept, the ones he’d left behind. He had dared to hit her once, and her rage had struck him back so quickly, felling him, he called her a witch, yelling, “Bruja,” as he fled our village.

I hemmed his trousers with quick, rough stitches. I stuffed his boots with scrap cloth so they would fit. I had the small, wide feet of my grandmother, the edges rough from years of running without shoes.

Like a silent prayer, I gave her my gratitude. Abuela had wanted me to play outside barefoot as much as I could stand, so that if ever I could not afford shoes, my feet could go without them. Now I understood what my grandmother had wanted, for me to keep my heart soft but the edges of me hard enough to survive the world as it was.

My grandfather’s poncho, I plunged into red dye, the rough agave taking it fast.

At night, the color wouldn’t show. But I would feel it against my skin.

I would not let this rage kill me. By using it, I would drive it from my body. I would turn it against the last man who would not save Léon. The man, who, by dawn, would be robbed of his finest things.

Oropeza’s guards, I took first.

I neared the hacienda with my head lowered. My hat hid the red of my hair. The brim shaded my face. I left the guards no chance to wonder if I was some messenger boy bearing midnight news, or whether they should draw their brass-throated pistols. I let my rage stream into them. I let it become liquid and alive.

They fell, one gripping his side, another holding his chest as though the venom clutched his heart.

Anything I could carry, I stole. Fine cigars. Money and papers from the desk drawers. Jewels that had once belonged to Oropeza’s wife; Abuela was sure he had killed her with his cold heart as well as we could with our poison.

I slipped through the house, the moon casting clean squares of light through the vestíbulo windows. The strap of my woven bag cut into my shoulder, heavy with all I had taken.

The rustling of grape leaves outside and the tangle of voices stilled me.

Oropeza and his friends stumbled drunk through the dark grapevines. Calvo and Acevedo and other men with more power than sense and more money than mercy.

They laughed. They swapped echoes of the same questions.

“How much are los franceses giving you for the traitor?” Calvo asked.

“How did you even manage this?” Acevedo asked. “I thought the only Frenchmen you knew were the ones you’d had shot.”

“Why didn’t I think of this?” another man asked.

“Because you’re not as smart as I am,” Oropeza said.

A question had just formed in me when I saw the figure held between them, being shoved forward and made to walk. Blindfolded, his wrists bound behind his back.

Because he could not see, he stumbled, drawing their laughter. The long points of their boots needled his shins.

They were forcing him toward the road that ran behind Oropeza’s estate.

My gasp was sharp as the first breath waking from a nightmare, the moment of wondering if, as in those dreams, my fingers were made of lightning or the sky was truly a wide blue blanket woven by my abuela’s hands.

Léon.

They hadn’t let the firing squad take him.

Hope bubbled up under my rage, but with it my anger thickened.

They hadn’t killed him, not yet. Instead, Oropeza was trading him to the country that now considered him an enemy. Trading him for money, for favors, for the currencies of men who owned so much ground but never bent down enough to touch it.

He was surrendering El Lobo to the country that called him Le Loup, the country Oropeza declared his enemy but still bargained with in secret.

My hope lifted my rage higher, driving it into a swirling cloud that flew out the windows and rushed at the men. It caught them, striking them down like el Espíritu Santo had slain them.

But this was not God’s work. This was not the Holy Spirit filling these men. This was the work of una Roja. A poison girl, veiled in men’s clothing.

The men fell to the ground, holding their throats and chests and sides. The richest ones, the ones whose boots had the longest tapered points, twisted to keep from stabbing themselves with their own shoes. Oropeza jerked as though demons poured through him. My vengeance, a vengeance I shared with my grandmother and all Las Rojas, was toxic as thorn apple and lantana. It was poison as strong as moonflower and oleander.

I threw open the glass-inlaid doors to the back gardens. I stepped between writhing men and grabbed Léon’s arm, pulling him with me. I caught the smell of his hair. Even now, it held the scent I’d come to think of as the countryside in Alsace. Dust and rain on hills. Fields covered in the blue of flax flowers and the gold brush of oats. He’d brought it with him on his skin. And when he told me the brown of my naked back reminded him of the deer that roamed that land, he gave me a place in his country.

Even through my rage and my fear, my lips felt hot with wanting to touch his skin. They trembled with wanting to give him my name.

Oropeza gazed up at me. His face showed no recognition, only the fear that I was a boy born of robbers and devils.

Through the open doors, Oropeza yelled into the house for his servants. He called them stupid and slow. He called them fools.

They ran across the tile. But when they saw the scene, when they saw the writhing men, and me, and the blindfolded man I had stolen from their patrono, they sank to the floor. They clutched their stomachs as though they, too, had been poisoned.

My breath stilled with worry that I had made them ill, that my venom was in them even though I had no rage for them.

But they caught my eyes, and smiled.

They twisted as though I was striking them down, so they could not be blamed for letting me rob Oropeza.

They had heard the stories. Las Rojas. They noticed the wisp of hair falling from my grandfather’s hat and onto my neck. They saw me as the poison girl I was, a daughter made of venom, even as I hid in my grandfather’s clothes.

I held on to Léon, leading him around the stricken men.

Oropeza and his friends would not die, not tonight. But they would thrash on the tile and the dirt until I was too far for my anger to touch them.

“Who are you?” Léon asked. His breath sounded short more from trying to press down his fear than from how fast I made him walk.

I cut the rope off his wrists and pulled off his blindfold and kissed him as fast as if I had more hands than my own. I didn’t care if the act would reveal me. My rage kept these men down like a blanket over a fire.

Léon’s lips recognized mine. He kissed me harder, setting his hands on my waist to hold me up.

“Go,” I whispered, my mouth feathering against his jawline.

Now he smelled like sweat, and the bitter almost-rust tang that I swore was the last trace of his fear. But under these things I found the smell I remembered. The warmth of flax and oats, things his family had grown for so long his skin carried the scent across the ocean.

“You have to run,” I said, my forehead against his cheek.

“I’m not going anywhere,” he said. His breathing came hard. I could feel his heartbeat in his skin. “Not unless I’m going with you.”

I pulled away so we could see each other as much as the dark let us.

“They took you because you stayed for me,” I said, still keeping my voice to a whisper. “I am poison. Don’t you see that?”

Léon set his hand against my cheek.

“Emilia,” he said, quiet as a breath. He meant it for no one but me.

The wind hid the strain of his breathing. The far lamp of the moon turned the gray of his eyes to iron. The sound of my name made me feel like the cloth on my body was blazing to red, my hair a cape as bright as marigolds.

“You are here and I am alive.” Now his accent turned sharp, not his practiced Spanish. “So tell me what makes you poison.”

He put his hand on the back of my neck and kissed me, this boy who wanted to belong to the girl I was, brown and small and poisonous.

To the men, we might have looked like two boys, one pressing his mouth to the other’s. Tonight, we would pull off our shirts and trousers for each other. Léon would be a boy, no matter the shape of his chest beneath his shirts. And I would let my hair fall from my grandfather’s hat and be the girl I had always been to him. For Léon, I would put on my best enagua just so he could push the soft cotton of the tiered skirt up my thighs. I would let my breasts lay against his skin. I would kiss where the rope had cut into his wrists and the cloth into his temples.

I wanted to protect his body as though it were mine.

But my own, I wanted these men to see it, and remember. I wanted them to know that I was my abuela’s granddaughter, that I carried the blood of poison girls.

The men still lay on the floor, gripping their chests and ribs.

I lifted my red poncho and my shirt, and I showed the men my breasts.

The moon lit the rounded shapes. It lit the fear on the men’s faces, the horror on Oropeza’s.

I gave them only that one second, just enough to let them wonder in the morning if they had imagined it, and then I let my shirt fall.

I reached for Léon. But it was not the men he was watching, or even me. He stood in the moon silver on the vestíbulo floor, looking out toward the hills. He lifted his face to the sky, breathing like he was taking a drink of the night itself.

And the wolves came. They came with their claws ticking against the ground and their muzzles stained with the blood of their last prey. They came with coats the same red gold as the hills they had run down from. They came with their backs streaked dark as the ink of the night sky.

I drew back from them, the wolves now crouching at the edges of Oropeza’s property. Then I caught Léon’s smile, slight but intent, telling me we had nothing to fear from them.

Léon took my hand, and we ran down the steps, the wolves filling the space behind us. They stood as guards, moving toward Oropeza’s men only when the men moved to pursue us. When the men lifted their heads to watch us run, the wolves showed their teeth. When they shouted curses at us, the wolves growled and snapped.

That was how Léon and I left them, both of us showing hearts so fierce these men considered them knives. We fled from the feigned cries of the men and women who worked for Oropeza but who loved us for defying him. We fled from the howls of men who wailed more for their pride than their bodies. We left them with the salt-sting memory of us, a brazen girl, and a boy with a heart so fearless wolves were his guardian saints.

Many stories found us after that night. Some said the French soldier known as El Lobo had called down from the hills a thousand wolves who not only scattered the men but ravaged Oropeza’s grapevines. Others said a girl known only as La Roja poisoned them all with her wicked heart, hiding the red of her hair so they would have no warning.

Some said El Lobo and La Roja were enemies, rivals, the girl capturing the French soldier just so she could have the pleasure of killing him herself. Others said La Roja stole El Lobo, only to fall in love with him the moment she first touched him.

When we hear word that every rich man who witnessed that night has died, I will tell the rest of the story. I will say what we have done since that night. What haciendas Léon has called wolves to destroy. What merciless hearts I have poisoned with the rage in my own. All that La Roja, the girl with the red hair and the red cape, and El Lobo, the boy as feared as wolves, have done.

But this is the part I will tell now. We rode off on Oropeza’s finest Andalusians, the wolves’ call at our backs. We vanished into the midnight trees faster than first light could reach us. We lived. We survived to whisper our names to each other even if we could not yet confess them to anyone else.

* * * * *