Читать книгу The End Of Mr. Y - Scarlett Thomas - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFIVE

PATRICK HAS BOOKED A HOTEL somewhere over by the ring road. We walk through town to the underpass and then, once we come out from that, down the main road towards the hotel. This is a night-time space, with neon signs hanging off takeaways, video shops, late-night supermarkets and nightclubs. We check in and walk up a broad wooden staircase to our room, which is airy and clean, if a bit shabby with age. While Patrick changes, I stand in the bathroom contemplating myself in the mirror. Am I cursed? I don’t look cursed. I look as if I have caught myself unawares, washed out and dazzled in the fluorescent light.

Would you read a cursed book, if you had one? If you heard that there was a cursed book out there and you found it in a bookshop, would you spend the last of your money on it? If you heard there was a cursed book out there, would you go searching for it, even if no one thought any copies existed any more? I think about my conversation with Wolf last night and wonder if life is as simple as ‘there is a book’. But again I think about stories and their logic and wonder if there can be any such thing as simply ‘there is a book’. Once upon a time there was a book. That makes more sense. There is a book. And then what happens? There is a book and it contains a curse and then you read it and then you die. That’s a proper story.

I come out of the bathroom and find Patrick wearing expensive-looking blue jeans and a pale pink shirt. He doesn’t look bad in jeans, but I preferred Burlem’s look: the black shirt, the dark trousers and the trench coat. But Burlem’s not here, and Patrick is. After flirting for a while, we go for dinner and have a strange conversation about nineteenth-century poetry, during which I go on and on about Thomas Hardy, and how the best bit of his poem ‘Hap’ is his invented word ‘unblooms’, as in: ‘And why unblooms the best hope ever sown?’ The whole poem is about wishing for evidence of a vengeful god – since there certainly isn’t any evidence of a benevolent one – because a higher power, even a cruel one, gives us meaning in a way we can’t give meaning to ourselves. This ends up with us talking about structuralism and linguistics (Patrick’s specialism), and then Derrida (one of mine).

‘How can you read Derrida?’ Patrick asks me at some point.

‘How can you not?’ I say.

We’ve finished dinner, and I realise that I am now having the conversation as if I were a robot taking part in the Turing Test. I can probably convince Patrick that I am human and listening to him, but really I’m thinking about Mr. Y.

‘Are you OK?’ he asks.

‘Yeah,’ I say. Perhaps I should try harder. ‘Have you ever listened to any of Derrida’s lectures?’

‘No.’

‘You should. I’ve got one on my iPod. In it, he says that praying is “not like ordering a pizza”. I love that. I love the little image of Derrida spending an evening praying and ordering pizzas to prove they’re not the same thing. Not that he would have done. I mean, I can’t see him praying, or trying to prove something by experiment. I bet he ordered pizzas, though.’

Patrick is grinning again. ‘It’s unbelievable,’ he says.

‘What, Derrida praying?’

‘No. The fact that I’m about to sleep with someone who owns an iPod.’

Our roles in bed are quite simple. I am the eager young student and he is the slightly sadistic professor. We don’t go so far as to actually act out our parts, and his slight sadism doesn’t extend further than occasionally tying me up with silk scarves, but I like it when he tells me what to do.

By the time I wake up the following morning, Patrick has had breakfast and left. There’s a card on the bedside table thanking me for a wonderful night and explaining that there’s been some sort of ‘crisis’ at home that he needs to attend to. I wish I’d brought my book with me. I have a large room-service breakfast and read a complimentary newspaper before getting up and making the most of the hot water. The water in my flat never seems to get anywhere beyond ‘fairly’ hot, but I like water with which you can actually burn yourself.

As soon as I am washed and dressed I walk back into town and along the dilapidated city walls towards my flat. The ring road runs next to me on my left, and the landscape I can see is a confused mess of cars, shops, road signs, bollards, a petrol station, some cranes in the distance, a pub, a roundabout and a pedestrian bridge. At some point a train goes past, emerging from behind a billboard advertising shiny cars and disappearing again behind a nightclub. Every kind of urbanity seems to exist in this space, from the city walls themselves to the remains of the Norman castle and the ugly red blocks of flats that have gone up next to it. Beyond the castle there’s a subway under the ring road, and if you go through it you can walk along the river towards the motorway, passing the gas tower and the encampment of homeless people who live in tents. I walked that way once, curious about the local countryside. There was a smell of gas all the way.

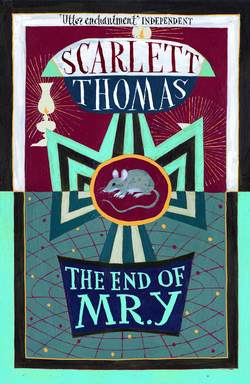

When I get back there’s no sign of Wolfgang’s bike, so it looks as if I’m going to be on my own with the mice. When I look, I’ve got two full traps, so I take them downstairs and release the mice out the back by Luigi’s bins. Back in the kitchen I reload the traps with stale biscuits and put them back under the sink; then I put coffee on the stove and arrange all my things around the sofa: The End of Mr. Y, cigarettes, notebook, pen. As soon as my coffee is ready, I curl up on the sofa and begin reading where I left off yesterday morning.

The moment the liquid struck my tongue I became aware of several new sensations, including a sudden aversion to darkness and a heavy, constricted feeling. At first I felt sure that these were simply delusions occurring because of the rather melodramatic manner in which the fluid had been prescribed, and that I was simply falling prey to fancies. However, after a time I began feeling increasingly anxious and experiencing something like vertigo. Nevertheless, I fixed my attention upon the black circle, as instructed, beckoned once again by curiosity’s claw. I remained convinced that, if this fair-ground doctor was, as I suspected, a fraud, then nothing he could do would cause me any harm.

After lying on the hard slab staring into the black circle for several moments I was startled to see it begin to disintegrate before my eyes. Two larger circles took its place, one pink and one blue, and these shapes then appeared to expand and contract with the soft translucency of jellyfish. I was suddenly overcome with the feeling that one has when moving downhill on a switchback ride, or in the dreams of falling that one has from time to time. It was not my physical being, however, which was descending, but rather my mind. It was as if the thinking, reasoning part of my being was closing with the finality of a heavy, locked door. In its place a small aperture appeared, growing larger and larger until it eclipsed the black circle on the small piece of card, and continued to enlarge until it was the size of a railway tunnel. I was alarmed to realise that I was now moving down this tunnel at a giddying speed.

The walls of the tunnel were charcoal-black at first but presently I became aware of various inscriptions on the walls which appeared alongside me as if drawn by light. At first these were simply pinpricks, like little stars in the firmament, and I fancied that if one could connect them, then perhaps a picture would form. There were also oscillating lines of the sort one might observe in the crude representation of a wave in the sea. For one instant I fancied I saw before me pictures of the human genitalia. There then appeared various shapes, and, despite the tremendous speed with which I passed them, I observed several circles, spheres, triangles, pyramids, squares, cubes and rectangular parallelepiped objects until these faded and the walls of the tunnel then became adorned with what appeared to be ancient hieroglyphics, which I confess I could not read. These little pictures blinked like apparitions as I passed them: I saw things that looked like birds and feet and eyes. All of these impressions appeared before me as though drawn with light.

I became aware of my anxiety paling as I continued my journey through the tunnel, and I was intrigued by the little symbols that flowed past me as if projected on a phenakistiscope. I saw many circles bisected with a cross or a line, and an abundence of other shapes including those which resembled little flags, stalks, boxes, and the reversed Roman letters g, E, r and P. I also saw what appeared to be Roman letters as if drawn in the hand of a child. However, it was clear that not all the Roman letters were present, and their expression seemed to vary between upper and lower case. I am sure I only observed the letters y, I, z, which was crossed in the French style, and l, o, w and x. Later there also appeared the upper case characters A, B, H, K, M, N, P, D, T, V, Y and X. Presently the Greek letters appeared in sequence, from alpha, beta, gamma and delta through to phi, chi, psi and omega. Then I observed the Roman alphabet in the correct sequence, from A through to Z. Still there appeared hieroglyphics here and there. The further I journeyed into this long tunnel, the more characters I perceived on the black walls, until there was more light than shade, and thousands of characters jostled before me. I saw Roman numerals and Arabic numerals and other shapes I could not discern, for they flew past me with such tremendous velocity. There were also mathematical equations. I recognised Newton’s F=ma but none of the others.

Presently I began to sense that my journey was almost at an end. The light on the walls of the tunnel eventually expanded so that I felt bathed in it. Indeed, for one curious second I fancied myself to be part of the light itself. I could no longer perceive anything around me but for this bright white glow. I remember quite distinctly thinking, ‘That’s it! The penny showman has killed me. Now I shall see what Heaven is like.’ I did not think of the other place. And, after a short time, it did appear that I had awoken in a heavenly landscape. I did not find myself confronting Saint Peter, however. Indeed, there were no other beings, mortal or otherwise, to be discerned on the softly rolling meadow I saw before me. Under a bright blue but curiously sunless sky, I observed grass, flowers and trees of species to be found anywhere in the nineteenth-century English countryside. I admit that at that moment I experienced the most profound sensation of peace, which was most welcome after the creeping dread with which I had become familiar at the start of my journey.

How long had I been travelling? I had no idea. In the depths of my mind something gnawed at me with persistent little teeth. Did I have an assignment in this place? I recollected the fair-ground doctor and his strange potion, and then the reason for my journey arrived once again in my mind. I was here to see the workings of Pepper’s Ghost, although I had no idea of how this could be achieved, and also felt that my appetite for solving this mystery was a very slight pang of hunger indeed in comparison with the greedy desire I now felt to solve the far bigger mystery with which I had been presented: where was I and how had I come to be there?

At the same moment that my assignment had reappeared in my mind, so a small piebald horse had appeared in the meadow to the right of my current position. The horse presently came and nuzzled at my hand, and, noticing that it was fully tackled, I understood that I was supposed to ride it. I have some experience as an equestrian and I saw no option than to insert my foot into the stirrup, swing myself onto the animal and take the harness. With only the merest of nudges, the horse moved gracefully forward. Again I had the sensation that I knew something I could not know, and fancied that the horse would take me to the place I needed to go. This sensation was a powerful one and so I let the horse trot onwards, towards the brow of a small hill. All around me was calm and tranquillity and I felt as if I could remain in this place for ever and not want for anything. Yet I felt compelled to complete my assignment.

I soon became aware of several dwellings ahead of me. As my horse drew closer I saw that there was indeed a small hamlet of cottages clustered before a vast and tangled forest. I understood that I was supposed to examine these dwellings and so I dismounted from my horse and tethered him outside the first cottage. This was a dark little place, with a garden overgrown with brambles and thick, twisted trees. Even before I saw the name on the gate, I knew that this was the fairground doctor’s house. The next place was plainer, with a whitewashed exterior and a name on the gate that I did not recognise. Something told me to enter this gate and I did so. Again, this something that seemed to speak from within my mind told me that the door would be unlocked, and so I entered without knocking, knowing that according to the customs of this place this action would not be considered aberrant.

Then I experienced the most peculiar sensation of all. Language almost fails me when I try to formulate this sensation in words. The closest approximation is this: imagine stepping not into another man’s shoes but, rather, into his soul. Even as I write this, that paltry description appears feeble in comparison to the odd, but not at all uncomfortable sensation of expansion that I felt as whatever is ‘I’ grew, as if from a seed, into whatever was ‘him’ and the two of us became one. All at once I intuited what had occurred. Inconceivable and impossible though it may appear, I had entered the mind of another. I had entered the mind of the illusionist Mr. William Hardy, proprietor of Hardy’s Ghost Illusion and Theatre.

I can assure the reader that the telepathic intercourse one has with another is in no way partial, vague or insubstantial. For, although I still seemed to carry with me the portmanteau of my own being, once inside this man’s mind I had the palpable sense that I existed not in his place, but alongside him. Much though it vexes me to write these words, for I am a man who does not believe in ghosts, phantoms and the so-called fourth dimension of Zollner and others, I have no doubt that I shared the mind of this man. I could think what he thought, I knew what he knew, and, for the time that I remained a guest in his being, I experienced what he experienced.

He (although it seemed to me that ‘I’ did all that follows, I will not confuse the reader here with the first person singular or, worse, the plural) was hungry; this was the first sensation of which I became aware. Of course, I experienced the same hunger, now that I was inhabiting the same being, and, without thinking what I was doing, I cast my own mind back to the last time I dined. I quickly perceived something reminiscent of two transparent images placed on top of one another. Of course, this does not adequately explain the sensation but words will not allow me a fuller description. I saw, or felt, myself taking luncheon at the Regency Hotel, but at the same time experienced William Hardy, who, I understood, likes to refer to himself in his own mind as Will, or even ‘Little Will’, a pet name given to him by his mother, sitting down to consume a steamed meat pudding wrapped in paper. It is with some difficulty that even I myself believe my own recollection as I write these words, but I certainly experienced the illusion of being able to taste the heavy, thick suet pudding and the dense brown gravy, as sweet as the meat inside. Nevertheless, I, or he, or we, still felt hungry. The meat pie was merely a memory and Little Will wanted his supper.

Before supper, Little Will had to pack up his ghost illusion. The fair would be departing the following morning and so everything would have to be carefully disassembled and stored in a large wagon. Will found the idea of this task rather overwhelming, as did I, and I quite understood his anguish and frustration as he barked orders at his underlings, wanting them to hurry this moment and take more care the next. I understood why he felt betrayed by his assistant Dan Roper, and I instantly knew that Peter, the boy helper, was too clumsy for this task. I do not believe that I shared William Hardy’s exact thoughts while the packing-up process was in progress; I was not ‘mind-reading’ in the crudest sense. Rather, I had access to his memories in the same way one accesses one’s own memories. Images came to me as fast as quicksilver. I saw, for example, the hapless boy Peter breaking a large sheet of glass, and was aware that this event had occurred at some time in the recent past. I saw Dan Roper creeping behind a grubby fair-ground tent with a woman. Then I saw Little Will with the same woman. Of course, I did not see him from above, like an omnipotent observer. I was his eyes, ears, nose and flesh as he coupled with this woman, barely a girl, whom I now knew to be called Rose.

I confess that I almost became lost in this new world, for, given access to another man’s thoughts, who would not roam endlessly within them? What anthropology or biology was this, that I was able to read another’s mind as if it were a play? I sincerely believed that the entire works of Shakespeare shrank in comparison with the tragedies, comedies, betrayals and desires of this one fair-ground entertainer. Still, however, I recalled my assignment. I was here, in the mind of William Hardy, to understand the ghost illusion that he peddled from country fair to country fair.

In an instant all was clear to me. I saw the intricate placing of the large, expensive sheet of glass, polished five times a day by Little Will himself. I saw it balanced on the stage, resting against a wall or structure behind. I saw, and understood, the forty-five-degree tilt. I had the most profound knowledge of the way the illusion worked, from the tilted glass to the actors underneath who danced in a projectionist’s light, thus creating images, like inverted shadows, to be reflected through the glass and onto the stage. I understood Little Will’s amazement when he himself first discovered the construction of these beings of light, and I recalled, as clearly as if thinking of a scene from my own past, the evening that Little Will opened the book that revealed the secrets of this illusion. I must say, however, that the sensation of reading a book in a man’s memory was a queer one, and although many passages were forgotten, and therefore appeared to be missing, I was able to read the most significant sections as if the book was in front of my own face.

There is a part of my adventure that I have not yet described for fear of entirely compounding the impression that I lost my wits that day in the fair-ground tent. However, I must now relate this curiosity, and I beg further indulgence from the reader. What I wish to describe is the way in which my field of vision altered when inside this ‘spirit world’ of other minds. At the beginning, I confess I had no idea of how far this world-of-minds expanded, nor how far within it I would be permitted to travel. However, on that first visit I became aware of some important factors, which I will now attempt to describe. When one sees the world in ordinary social intercourse, or in the comings and goings of a typical day, one sees the world as if that world were contained within a frame. The outside world therefore is a picture on a wall; or, perhaps, many pictures. If I were to look to my left I would see one picture. If I glanced to my right, another. A philosopher may ask if indeed there is another picture behind me, one which I cannot see, but I shall not take this avenue of inquiry for the time being.

If one accepts this way of looking at the world as a frame with perceptible edges, albeit blurred ones, then one will more easily comprehend the altered frame through which I gazed on the world of Little Will. For Little Will’s frame also contained my own, superimposed on top of it. The result of this superimposition was the existence of a milky hue over all that I saw, as if I were looking through thick glass or a thin veil. Yet the peculiarities of this new frame did not end there. Around the edge of my perception of Little Will’s vision was a blur similar to that which creeps around the edge of ordinary vision. But the blur around the edges of Little Will’s frame was made more pronounced by the existence of layers of little pictures, like playing cards laid out in a game of Patience; one to the right and one to the left. There was another feature of this new kind of vision which perplexed me even further. When Little Will came close to another person and regarded him, a dwelling would appear faintly behind the already milky image that I had. I understood without fully comprehending that at these moments I could, if I so wished, simply walk into that house instead of the one in which I was currently standing; in other words, I could enter another mind. At least, this was the theory I constructed from the evidence before my eyes, but when I tried this on the boy Peter I seemed to bounce from an invisible wall and instead landed back on the small path connecting the cottages.

Again, I was overcome with a sense of peace and fullness. The hunger I had felt when joined with Little Will immediately subsided and I realised that spending time in another man’s soul was terribly draining. Out on the open landscape I felt no discomfort, but I remembered the sensation of privation and desperation I had shared with Little Will. I concluded that the further adventures I so craved were best left for another visit, and so I retrieved my horse and let him take me back to the place from which I had entered this world.

The journey back through the tunnel appeared of a far shorter duration this time, and presently I arrived, if that is the right term, for an observer would not have seen me leave, on the slab in the fair-ground tent. Once more I could hear the rain on the thick canvas, and I struggled to open my eyes on the familiar world I had left behind for a time. With my eyes still half-closed, and my head thick with fancies, I asked myself whether I had concocted an elaborate dream or whether I had in fact telepathed into another man’s mind, and resolved to interrogate the fair-ground doctor the instant I had fully regained my senses. However, when I opened my eyes I found myself alone in the dark. The vulgar lamp, which had been burning brightly before, was now extinguished. The doctor was nowhere to be seen. I withdrew my watch from my pocket, along with a box of matches, and, after striking a match close to the face of the timepiece, found it to be past eleven o’clock. Startled, I immediately got to my feet and felt my way out of the tent, using another match to guide me. How could I possibly have been unconscious for such a long period of time? I confess I felt frightened as I stumbled out of the large theatre tent and into the open air of the darkened, deserted fairground. I was determined to find this doctor and admonish him for leaving me alone and defenceless for such a long time. However, the doctor was nowhere to be seen and, now tired and desperately hungry, I made my way back to the Regency Hotel, resolving to find the doctor the next day.