Читать книгу Spoke - Scott Crawford - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление“All I ever wanted then—and now—Was to get the whole room singing.” —Ian MacKaye

When the Extorts broke up after playing just one show, vocalist Lyle Preslar found himself without a band. By November 1980 The Teen Idles had broken up as well, and bassist Ian MacKaye decided he wanted to sing for the next band that he and drummer Jeff Nelson were envisioning. Knowing that Preslar was a guitar player, they asked him to join the new project. He recommended asking Brian Baker, a friend of his from high school, to play bass, and barely a month later they played their first show as Minor Threat. The band would come to represent DC hardcore to the world. They had the benefit of their own label, Dischord Records, which was run by Ian and Jeff. They would be the first DC band to tour extensively. They had speed, rage, chops, and authority. The stance they took on “Straight Edge,” from their self-titled 1981 debut EP, would name and codify a way of life that at times did not sit well within the band.

The records, however, are marvels, better produced and recorded than almost any other punk band this side of the Sex Pistols. The Baker/Nelson (and later Hansgen/Nelson) rhythm section thumped out a foundation as fat as any early-seventies English glam record. By their farewell single, Salad Days, Minor Threat was so good and showed so much promise, you cursed the band for destroying it by breaking up.

MacKaye would go on to form another great band in Fugazi, after making music with Embrace, Egg Hunt, and Pailhead. He remains active these days with The Evens. Preslar played with Samhain and The Meatmen before going into A&R at Caroline Records and later becoming a marketing director for Sire Records. Nelson joined MacKaye in Egg Hunt and also played with Three and The High Back Chairs before settling into graphic arts and political activism in Toledo, Ohio. Baker’s guitar has elevated Government Issue, The Meatmen, Dag Nasty, and Junkyard, with Bad Religion now being the steadiest gig of his career. Steve Hansgen went on to produce Tool’s debut EP, Opiate. But for all their outstanding endeavors over the years, it might be what these gentlemen did as Minor Threat that will truly endure. —Tim Stegall

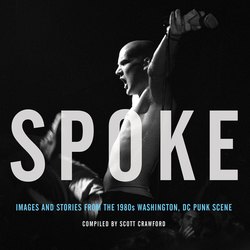

Ian MacKaye, Wilson Center, DC, 1981 (MALCOLM RIVIERA)

STEVE HANSGEN: The first time I saw Minor Threat was when they opened for Black Market Baby at the old 9:30 Club in 1981, along with SOA, and we’d heard in Virginia about both bands, and we were really excited to see these new bands that had come out of the ashes of the original DC punk rock bands, and we weren’t disappointed. That night was pretty remarkable, and I’ve heard other people who had seen them before—and they’d only been playing since December at that point, and this was like April or March—I’d heard that this show was something different. I remember they came out and announced that they were no longer Minor Threat, they were called Fifth Column, and they went into their set, and they were shockingly tight.

IAN MACKAYE: All I ever wanted then—and now—was to get the whole room singing. I never stopped singing when I’d put the mic out in the crowd. I remember seeing bands do that and thinking, Now you’ve fucked up. We’re all supposed to be singing—when you just put the mic out and stop singing, you’re just leading, it’s not about the music anymore.

Lyle preSlar (Jim Saah)

SIMON JACOBSEN: When we used to play shows with Minor Threat, I used to scowl to myself because they were just much more talented and innovative musically than primate muscle-neck SOA. All of our music came from what we could manage at the time with our sophomoric talent and zits. Minor Threat played with their brains and hearts. Henry was singing about his mother for the most part, but Ian was singing about activism and much larger issues that mattered to people.

Brian Baker, 9:30 Club, DC 1983 (Jim Saah)

STEVE HANSGEN: He walked like he was in charge, and that was very impressive, because we had heard about Ian out in Virginia, but it was like whispers, like, “There’s this guy, and he does this thing, and wow.” When you saw him, it was very clear that this was somebody.

JON WURSTER: You listen to those Minor Threat records and they were just kids but they could really play and the songs were great and Ian’s voice was unlike anyone else’s. They just had a very unique, instantly identifiable sound.

Jeff Nelson, outside Woodlawn High School, VA, 1981 (Malcolm riviera)

IAN MACKAYE: Going on tour back then, it was pretty normal to be attacked onstage. People thought it was punk to attack the singer, or they thought we were some sort of fundamentalist, fascistic straight-edge guys. We would literally fight on the stage. It was just the nature of things. We played in San Francisco and people threw fireworks at us and spiked my Coke.

SIMON JACOBSEN: For DC at that moment, Minor Threat and Bad Brains were the answer. They seemed to fill the holes that people had in their hearts and then provided a direction for all of that energy to be positively focused. They also helped create the road map of the complexity and composition for the next generation of postpunk music in the US.

DANNY INGRAM: As far as I’m concerned, there were two bands in DC at that time that set a very high bar to which the rest of us could aspire: Black Market Baby and the Bad Brains. I think the first band to really get this was Minor Threat—and you could tell that after The Teen Idles, Ian and company took their songwriting and focus to a whole new level—eventually surpassing those initial inspirations.

Ian Mackaye, wilson center, dc, 1983 (Jim SAAH)

THURSTON MOORE: I bought In My Eyes and I thought it was just incredible. It was one of the most powerful records I had heard, so I went back to the store and I bought the first Minor Threat record and I bought the SOA record and the Youth Brigade record, then Legless Bull came out and there were all these records out on this label and I got really into it.

IAN MACKAYE: Even before I got into punk rock, I didn’t drink. People used to say I made them nervous at parties. They used to called me “the group conscience.”

MARK HAGGERTY: When Minor Threat were on tour, Ian would sometimes ask for water from the stage and people would hand him cups filled with water that was spiked with vodka. He took a lot of shit for straight edge.

wilson center, dc, 1982 (MALCOLM RIVIERA)

JOHN STABB: If it’s true that everybody in DC didn’t smoke, drink, or fuck, we wouldn’t be punk rock, we’d all be monk rock.

IAN MACKAYE: I still get crank calls to this day from kids saying, “Hey, dude, I’m drunk! Is that freaking you out?” I’m fifty! Two days ago I got a crank call from a kid saying, “I never liked your fucking band ’cause you’re straight edge.”

jeff nelson (JIM SAAH)

JEFF NELSON: I got tired of being in a band that was either preaching about “Don’t do this” or “Don’t do that” or was being perceived as that, and it definitely caused some friction in the band.

CYNTHIA CONNOLLY: Ian approached me about designing the cover for Out of Step. I was like, “What are you thinking concept-wise?” Ian said, “I’m thinking about a black sheep running away from a flock of white sheep.” So one day I sat down to draw sheep and my mother had this issue of National Geographic on New Zealand. I see this flock of sheep on one of the pages and I just kind of used that as my guide. The black sheep I drew could have come out of a Dr. Seuss book. I got this box of crayons and drew a black sheep just once and it was done.

Ian Mackaye, 9:30 Club, dc, 1983 (JIM SAAH)

BRIAN BAKER: After two years of being a band, we got really good at fighting. Early on, fights would develop and factions would form and kind of move around. Sometimes it would be Ian and I versus Jeff and Lyle, sometimes Jeff and I versus Ian and Lyle. By the end it was basically Lyle and I banded together, which would explain the intensity and the quality of the arguments.

STEVE HANSGEN: We saw Trouble Funk together, and then I went back to Brian’s house, and he handed me a guitar and said, “Play.” I said, “I just want to tell you, I know every Minor Threat song.” “Really?” “Yeah,” and I just started playing them, and I knew them, boom-boom-boom, one after the other, and he said, “Okay. Well, here’s what’s going on . . . I’m going to play guitar [now] and we need a bass player. Are you interested?” I was like, “Am I interested?!”

TESCO VEE: I will not cast aspersions on their recorded output, but to truly experience Minor Threat’s breadth of pure punk fury, one needed to see them live. Pound for pound, the most awe-inspiring live set I’ve ever witnessed. The rancor they felt for each other on a personal level exploded onstage and those fortunate enough to have been in attendance were the grateful recipients. As good as it got.

minor threat’s last show, Lansburgh Cultural Center, dc, 1983 (Jim SAAH)

STEVE HANSGEN: Like any dysfunctional marriage, you get to a point where you have a choice: you can either break up, or you can have a baby, and the baby will solve everything. Instead of breaking up, which would have seemed odd to everybody if they had just gotten back together and broken up immediately, they had a baby. I was the baby, and I was going to make it all better.

BRIAN BAKER: It has to be remembered: this was our band that we did after school. Though it had achieved some level of success at that point, nobody had any inkling that it would have any resonance thirty years later, so it wasn’t precious to us.

Steve Hansgen: Playing those songs onstage with them in front of any audience was absolutely incredible, and being offstage was not very much fun. They really didn’t get along.

Previous four photos: 9:30 CLUB, dc, 1982 (TIFFANY PRUITT)

IAN MACKAYE: Brian and Lyle had started to rehearse with Glenn Danzig for an early version of Samhain before Minor Threat had even broken up.

BRIAN BAKER: We wanted to be a more commercially viable band.

Steve Hansgen, Wilson Center, DC, 1983 (Jim Saah)

IAN MACKAYE: There’s no question that Lyle and Brian felt like it was a conflict of interest that Jeff and I owned the record label they were on. But our position was, “We’re not making any money anyway, so why does it matter?”