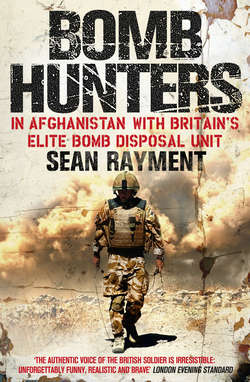

Читать книгу Bomb Hunters: In Afghanistan with Britain’s Elite Bomb Disposal Unit - Sean Rayment - Страница 8

ОглавлениеChapter 1: Living the Dream

‘Bomb disposal – it’s the best job in the world.’

WO2 Gary O’Donnell GM and Bar. Killed in action September 2008.

0345 hours, 10 March 2010, Helmand, Afghanistan.

The Hercules drops like a stone through the black Helmand sky, its four overworked engines groaning. Most of my fellow travellers are boyish-looking soldiers in crisp new uniforms – fresh meat for the Afghan war machine. Many of the soldiers are battle casualty replacements (BCRs), sent to Helmand at short notice to replace those killed or injured fighting the Taliban.

It’s a sombre journey. We all cling to our seats as the aircraft descends at an impossible angle. Beneath the dim, green glow of the safety lighting, a silhouetted soldier begins to vomit. The acrid smell of a partially digested meal drifts through the cabin and I feel my gag reflex kicking in. My comfortable, peaceful civilian world is inexorably slipping away. I begin to sweat profusely beneath my helmet and combat body armour, or CBA, scant but necessary protection against a missile strike or ground fire from an anti-aircraft gun. The lumbering aircraft begins to pitch and roll in a desperate attempt to avoid missile lock-on.

One of the crew is monitoring the ground outside with night-vision goggles, searching for the tell-tale flashes of anti-aircraft fire. A missile strike at this altitude would not be survivable. I wonder if the rest of the passengers, like me, are urging the pilot to fly faster. No senior military official will admit it publicly but the current thinking in the Ministry of Defence is that is just a matter of time before the Taliban acquires surface-to-air missiles and manages to shoot down a troop-laden Herc flying into Helmand. Such a catastrophic event, the loss of dozens of British troops in a single incident, could finally kill off the dwindling public support for the war in Afghanistan and signal the beginning of the end for the entire NATO mission.

A young Army officer sitting on my right conjures up a nervous smile but his eyes tell another story. It’s his first tour in Helmand and he has never flown in a Herc before. I attempt to allay his fears by giving him the thumbs up. But, in truth, I’m probably just as worried as he is. I’m not a good flyer at the best of times and all sorts of ‘what if’ thoughts are running through my head. Six hours earlier, when we arrived in Kandahar Air Force Base, known within the military as KAF, the young officer reminded me of a timid boy attending his first day at school. Fresh-faced and awkward, among no friendly faces, he sat by himself for several hours with his head buried in a Dick Francis thriller, before boarding the flight to Helmand.

I’m on board what they call the ‘KAF taxi’ – effectively a military shuttle flight into Helmand from the sprawling Kandahar Air Base. I’m one of more than 100 passengers flown into Afghanistan on an ageing RAF TriStar – it first came into service in the early 1980s and was already second-hand. Hopefully the aircraft’s engines are in better shape than the passenger cabin because that is well and truly knackered. If the TriStar was a civilian plane, I’m pretty sure it would be grounded. Parts of the interior are held together by 3-inch-wide silver masking tape and the toilet doors have a tendency to fly open while in use – ‘The in-flight entertainment,’ some wag commented – but, frankly, it’s good enough for ‘our boys’ flying off to war to fight and die for Queen and Country. The TriStar is straight out of the military manual of ‘making do’. It’s what happens when the armed forces have been underfunded for decades. It is, as one senior officer told me, a third party, fire and theft, rather than fully comprehensive, insurance package.

Afghanistan has its own unique smell – it’s the dust in the atmosphere – and it’s on the plane thousands of feet above the desert; for me it’s the smell of fear, death and courage, and there is no other smell like it. The fear, and also the excitement, of being in a war zone are already beginning to build inside me and giving rise to a mix of emotions. I have yet to arrive and already part of me is wishing that I was back home, in a warm, safe house with my family. Instead I’m just minutes away from landing in one of the most dangerous places on earth.

Fourteen hours ago I was sitting in the bleak departure lounge at RAF Brize Norton along with several hundred soldiers. All tired, all sad. For them the long goodbye had come and gone – they were just at the start of their six-month tour. Six months of fear, broken up by bursts of excitement and long stretches of unimaginable boredom. There is nothing romantic about front-line life in Helmand: it is hard, dangerous and dirty. Generals and politicians fighting the war from their desks in Whitehall might talk about the importance of nation building and national security, but for the soldiers at the bullet end of the war it’s all about survival. From the private soldier, who joined the Army because it was the only job available after eighteen years on a sink estate, to the Eton-educated Guards officer, winning is coming home alive and not in a Union Jack-draped coffin. Soldiers in Helmand fight for themselves and each other – grander notions are for others to hold.

It was the same for me when I served as a young officer in 3rd Battalion Parachute Regiment in Northern Ireland in the late 1980s. Every member of 3 Para knew why the British Army was on the streets of Ulster. We understood the politics, the tribal tensions and the history, but it mattered little to any of us. Soldiers do not fight for Queen and Country: they fight for each other. They do not fix bayonets with the government’s foreign policy objectives ringing in their ears: they do so because they are professionals trained to obey orders. It’s the same in Helmand today. Every soldier still wants to win a medal but he also wants to make it home in one piece.

But with glory comes a terrible price. In Helmand, a front-line soldier stands a one-in-ten chance of being killed or injured; those are not good odds. Looking around the departure lounge at RAF Brize Norton, I wondered which of my fellow passengers would not survive the six-month tour, and I doubt I was the only one with that thought in their mind. The atmosphere was subdued, depressing even. Some soldiers entered the room with eyes reddened by tears, doubtless wondering whether they would ever see their loved ones again. Part of me, sitting here now descending into the Helmand desert, wonders the same.

There was once a time when I thought that as a journalist I was safe in a war zone. It’s a foolish notion. Why should I be less at risk than anyone else? But I believed it nonetheless. I have worked in several war zones – the Balkans, Iraq, Northern Ireland – and I always thought death and injury were something that happened to others. Mainly soldiers or journalists who forgot to obey the rules or who simply pushed their luck too far.

That was until one of my best friends, Rupert Hamer, was killed while on assignment in January 2010 after the US armoured vehicle in which he was travelling was destroyed by an IED. He was working as a reporter alongside photographer Phil Coburn, and the pair were both attached to the US Marines Expeditionary Force when he was killed. They were part way through a two-week assignment and were returning from a shura, or meeting of elders, when the tragedy struck. Phil and Rupert were sitting beside each other inside a 30-ton heavily armoured Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicle when they hit a huge improvised explosive device.

The main charge was composed of ammonium nitrate powder and aluminium filings, and when these are mixed together in the right quantities the result is lethal. The explosive was packed into several yellow palm-oil containers buried about 15 cm beneath the ground. The detonator was probably made from a Christmas tree light, or something similar, with the bulb removed. The bomb was one of the largest ever seen in Helmand.

The MRAP more or less remained intact – the front and rear wheels and axles were blown off – but the shock wave which tore through the vehicle was devastating. Despite wearing helmets and body armour and being strapped into their seats, Rupert, Phil and four US Marines all suffered multiple injuries. Phil and Rupert were sitting side by side, but while Rupert died Phil survived, though the bones in his feet were smashed beyond repair and both feet were amputated. Four US Marines travelling in the vehicle were seriously injured and a fifth was killed.

Death in Helmand is random – it has killed the best in the British Army, possibly even the best of the best. Every soldier from private to lieutenant colonel – all the ranks in a battlegroup – have been killed in action in the province since 2006. Not since Korea has the British Army been in such a bloody fight, and every indicator suggests it’s going to get worse.

I last spoke to Rupert less than two weeks before he was killed. It was an unusually warm day in early January. He had called me from Kabul while waiting for a flight to Helmand. I was sitting on a chair in my garden, guffawing with laughter as he relayed in detail all the hilarious events that had befallen both him and Phil in the short time that they had been in Afghanistan.

Rupert was in good form, joking about the Marines’ lack of organization and saying that by comparison they made him look organized. My last words were, ‘E-mail me when you can, and look after yourself.’ As he set off for Helmand, I went to Austria for a week’s skiing holiday with my family. Rupert was killed on the following Saturday, 10 January.

The first thing my wife, Clodagh, said to me after I told her Rupert had been killed was, ‘It could have been you.’ At that moment I vowed never to return. Fuck it, I thought to myself. It’s not worth it. Not for a few stories for a newspaper. But even as the words formed I secretly I knew I would return. The problem for me is that I find war zones exciting places. There is a thrill to being under fire, even risking your life, always in the knowledge, of course, that, as an observer, rather than a protagonist, I was somehow invulnerable. Rupert’s death shattered that illusion, but as the shock of his loss gradually lessened I was soon beginning to convince myself of the need to return.

Rupert always said to me, ‘If you are going to report the war, then you have to see the war,’ and he was right. Just before I left, my 6-year-old son asked me why I was going to Afghanistan. ‘To carry out research for my book and to report on what is happening in the country,’ I told him, hoping that he wouldn’t ask me if I was going to do anything dangerous. ‘Why can’t you just get the information off the internet?’ he responded, looking confused. ‘Because that’s what somebody else has seen and witnessed,’ I replied. ‘I need to see what is going on for myself so that I can write about it.’ ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘I think I understand.’

So here I am on a C-130, ten minutes away from landing in Helmand, the centre of a war zone where every day British troops are being killed and injured. So much for never returning. And the news from the front line is not good. In Sangin, a town in the north of Helmand, six soldiers have been killed in the first week of March. Four of the dead were shot by snipers. Taliban shooters are good, and the Army is understandably nervous. Enemy snipers are feared and hated by all armies and run the risk of summary execution if captured. Snipers will go for the easy kill or one designed to shatter morale: the young soldier, the commander, the medic. Morale in Sangin had understandably suffered. Soldiers were being picked off at the rate of one a day. Although the sniper is guaranteed to generate fear, in Helmand the IED, the unseen killer, remains the soldiers’ worst nightmare. A step in the wrong direction, a momentary lapse of concentration, can mean mutilation, the loss of one or more limbs, or death.

Lose a leg in what is known as a traumatic amputation and you have just four and a half minutes for a medic to staunch the wound before you fatally ‘bleed out’. The time decreases with each additional limb lost, and that is why no quadruple amputee has yet survived.

IEDs are now being manufactured on an industrial scale – it is no longer a cottage industry. Bomb factories in some parts of Helmand can produce an IED every fifteen minutes. Made from pieces of wood, old batteries and home-made explosive, they are basic and deadly. The Taliban have already produced IEDs with ‘low metal’ or ‘no metal’ content, which are difficult to detect. So, as well as using equipment to detect bombs, troops also need to rely on what they call the ‘Mk 1 eyeball’, hoping to spot ground sign.

In Helmand the IED is now the Taliban’s weapon of choice and the main killer of British troops. The field hospital in Camp Bastion now expects to treat at least one IED trauma victim every day. Between September 2009 and April 2010 there were almost 2,000 IED incidents.

The human cost of this war has never been higher. Since 2006 more than 350 soldiers have been killed and more than 4,000 injured. Of these, more than 150 have lost one or more limbs. And those are the statistics for just the British forces. Every country with troops in Helmand – the United States, Estonia and Denmark – has suffered similar losses.

In one week alone in February 2010 there were 200 IED incidents – that is, bombs being detonated or discovered. Do the maths – that’s over 9,000 a year. Or more than one IED for every British soldier serving in Helmand.

The job of battling against this threat falls to the Joint Force Explosive Ordnance Disposal Group, part of the Counter IED, or CIED, Task Force. At the tip of the spear are the Ammunition Technical Officers, or ATOs, the soldiers who defuse the Taliban IEDs – the bomb hunters. Also called IED operators, the ATOs work hand in glove with the RESTs. It is a fantastically dangerous task, not because the devices are sophisticated but because of the volume of bombs. The number of IED attacks started to go through the roof in 2008, a development which was entirely unpredicted. Back then there were just two bomb-disposal teams in Helmand because someone, somewhere in the Ministry of Defence did not regard Helmand as a ‘high-threat’ environment. That was the official version of events but in reality Iraq was still the priority and there were simply not enough bomb hunters to serve in both theatres. The following year IEDs were killing more soldiers than Taliban bullets. By the middle of 2010 the CIED Task Force began suffering casualties on a scale which had not been seen for thirty years.

I’ve come back to Helmand to try to understand why anyone would want to become a bomb hunter. I want to get inside their heads, learn about their fears and concerns, the unimaginable stresses they face every day and what drives them on knowing that one mistake, one single slip, can mean death. For three weeks I will be an embedded journalist working alongside both the bomb-hunting teams of the CIED Task Force and the Grenadier Guards battlegroup.

It is virtually impossible to report from Helmand without being embedded. The risks are so great that independent travel is a non-starter. Travelling independently through Helmand could only really be achieved by striking some sort of deal with the Taliban in order to pass safely through areas under their control. Even if that were achievable there would still be every chance of hitting an IED or finding yourself in the crossfire of a battle between the insurgents and British troops.

Being an embedded reporter has its advantages, the most important being safety. To a certain extent journalists are exposed to the same risks as soldiers, but because you are not playing an active part in a battle you are not fighting through Taliban positions, so you have to be fairly unlucky to be killed or injured. But there are disadvantages. All of my copy will be scrutinized by censors who will check it for anything which could be construed as a breach of operational security. Before any journalist can embed with the British Army, he or she must sign the ‘Green Book’, a contractual obligation stating that the Ministry of Defence will scrutinize all copy, pictures and video before publication.

Most journalists don’t have a problem with this, even if it does run counter to the idea of a free press, and I for one would not want to write anything which might put a soldier’s life at risk.

The C-130 slams into Camp Bastion’s darkened runway, and the relief on board is tangible. The engines once again begin to scream as we slow to a halt. Beneath the green gloom of the safety lights, the troops begin to ready themselves for disembarkation. The Herc’s rear ramp opens, like a giant mouth, revealing a kaleidoscope of orange, yellow and white lights blinking through the desert dust. This is not a military camp, it’s a small city, dominated by the monotonous drone of departing aircraft, some carrying troops, others bearing the coffins of the fallen.

One by one we silently disembark, keeping our personal thoughts private, each wondering what the future will bring. Beneath a star-lit sky we are led in single file from the airstrip to waiting buses, before being driven to one of the ‘processing centres’ where fresh troops undergo their final preparations for war. The week-long Reception, Staging and Onward Movement Integration (RSOI) programme is effectively designed to fine-tune the soldier so that he can hit the ground running. In effect it’s the last chance to get things right before coming face to face with the enemy.

A two-tier war is being fought by the British Army in Helmand. The ‘teeth arm’ troops, those involved in the day-to-day fighting and killing, live in small patrol bases, where the conditions range from sparse to austere. Toilets are often holes in the ground, soldiers keep clean with a solar shower – a bag of water which has been left to bake in the sun – and meals are a mixture of fresh food and Army rations. Six months on the front line is a dangerous existence with few comforts.

But those troops who remain in bases like Camp Bastion or Kandahar Air Base live, by comparison, in air-conditioned luxury, with hot showers and fresh food, and where off-duty hours can be spent in one of the many gyms or watching premiership football on satellite television. ‘Life in the rear,’ as the American troops in Vietnam observed, ‘has no fear.’ The majority of those soldiers based at Camp Bastion will never set foot beyond its gates, but while they might not take the same risks as the front-line soldiers their job is just as vital. They keep the war machine moving by ensuring that the right food, water and ammunition arrive at the right place at the right time. It’s a job which lacks the ‘glamour’ of battle but is just as important.

The coach snakes its way through the camp, passing row upon row of huge tents which were once white but have now taken on the hue of the desert. I’ve been coming to Camp Bastion since 2006, and every time I return the place has grown. Someone once said that the best decision the British Army ever made in Helmand was to build the base in the middle of nowhere. Had it been near a town or an area of habitation, the chances are that it would have been mortared or rocketed every night.

Our belongings are dumped in the desert dust by an Army lorry and chaos ensues as 100 individuals search for the bags in the pitch blackness. The soldiers are told to collect their kit and move into one of the briefing rooms – I say goodbye to the young Army officer, shake his hand and wish him luck, silently hoping that he makes it home safely in six months’ time. The weary soldiers file into a tent to begin a series of briefings through which many will sleep. I’m left with the lasting impression that Camp Bastion is one giant processing centre. Every night hundreds of tired, nervous and confused troops arrive to feed the war machine, and every day, or almost every day, the dead, the wounded and the lucky fly out.

Twenty hours ago I left my home in Kent and kissed my wife and sleeping children goodbye and said a silent prayer as the first cuckoo of spring sang the dawn chorus. Now I am in another world, where the threat of death and violence is always present. Not for the first time I ask myself, what am I doing in Afghanistan? It’s 5 a.m. Helmand time, and finally I get some sleep.

Rupert Hamer was not the first person I have known to be killed in Helmand. While embedded with the Grenadier Guards in November 2009 I met Sapper David Watson, who was a member of a REST. He struck me as a quiet but professional soldier who was completely committed to his job. He was killed in an explosion in the Sangin area on 31 December. I met Sergeant Michael Lockett in 2008 when he was awarded a Military Cross after serving in Helmand in 2007. He returned in 2009 but was killed in action on 21 September, just a few weeks before he was due to return to the UK.

In July 2008 I was embedded with the Parachute Regiment for a short period at FOB Inkerman, just north of Sangin town. There had been a spike in Taliban attacks over the past two months and just two weeks before my visit a suicide bomb had killed three members of the regiment. On one early-morning patrol in which I took part, I met Lance Corporal Ken Rowe, a member of the Royal Army Veterinary Corps, and his dog Sasha. Everyone immediately warmed to both man and dog. I think there was something about Sasha that reminded everyone of home, but less than a week later both were killed in an ambush.

Then there was Warrant Officer Class 2 (WO2) Gary ‘Gaz’ O’Donnell. War is one of the few human endeavours that create real heroes, and one of those was Gaz. He was a high-threat IED operator – one of just a handful of soldiers gifted with the skill of being able to defuse home-made bombs in the most deadly place on earth.

I first met Gaz in Helmand in July 2008. I was told that Gaz was worth chatting to because he had a ‘nice collection of war stories’. I wasn’t disappointed. My lasting memory is of him sitting astride a quad bike dressed in just his body armour, helmet, shorts and a set of cool civilian shades. It was on one of the training grounds in Camp Bastion, where troops coming fresh into theatre are taught the basics of ‘Operation Barma’ – the process of locating and confirming the presence of IEDs in Afghanistan.

Gaz’s dress code broke all the rules, and the smile on his face said he was loving it. I liked him as soon as he shook my hand. He was a combination of unruffled calmness and mischief. His thick red hair was long and unkempt, as was his moustache. His obvious disregard for dress regulations was the flip side of his professional life, where his unwavering allegiance to a set of rules and self-discipline kept him alive. Gaz was already a veteran of Iraq, Northern Ireland, Sierra Leone and two tours in Helmand. He was a legend in the counter-IED, or CIED, world even before he arrived in Afghanistan.

Blazoned across his broad shoulders was a tattoo: ‘Living the Dream’. It was his motto. He had already won the George Medal in Iraq and was destined for another top gallantry award for his work in Helmand. Gaz lived to defuse bombs – it was his calling.

At 24 years old Gaz joined the Army relatively late in life. The delay was due in part to a failed experiment as a rock guitarist – another tattoo of a cannabis leaf, also on his back, was a memento of a more hedonistic life.

From the day he joined up Gaz wanted to become an IED operator. But it was to be a long haul. After passing basic training he was posted to Germany to serve in 3 Base Ammunition Depot, learning the trade of the Ammunition Technician. But when the opportunity came to take the Improvised Explosive Device Disposal Course, he passed with flying colours. A feat he also managed to achieve on the IED High Threat course, to become one of just a handful of bomb-disposal experts to pass the course first time.

Like every bomb-disposal operator, Gaz was keen to get involved in the thick of the action in Iraq, but he was forced to wait until 2006, by which time he was a staff sergeant, before he finally got his wish. The war had gone belly-up, primarily because of the complete absence of post-operation planning. After defeating the Iraqi Army and deposing Saddam, the US and British forces managed to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory. A Shia insurgency in the south quickly followed a Sunni revolt in the north. Reconstruction of the shattered state ground to a halt and al-Qaeda, the Islamist force behind the 9/11 attacks, managed to gain a foothold in the country.

By 2006, attacks against the multi-national forces in the south were a daily occurrence. With the help of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard the Shia insurgents managed to develop a range of highly sophisticated improvized explosive devices called Explosively Formed Projectiles, or shaped charges, which could penetrate armour and were detonated by infrared triggers.

These IEDs took a terrible toll on the British troops, killing and maiming hundreds, especially those travelling in the now notorious Snatch vehicles. These were lightly armoured Land Rovers once used to patrol the streets in Northern Ireland during the Troubles. Snatches were originally designed to protect troops from small-arms fire, rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) and shrapnel. When the insurgency exploded in 2004, the British Army found itself without a vehicle in which troops could conduct patrols in urban areas, and the Snatch was sent to fill the gap. But such was their vulnerability to attack that within months the troops had dubbed the vehicles ‘mobile coffins’.

By 2006 reconstruction plans for Iraq had become a faded dream. Troops rarely ventured out of their bases without being attacked. The first sign that the Iraqi people in the south were not as welcoming as the government and the top brass might have hoped had come on 2 July 2003, when six members of the Royal Military Police were attacked and killed by a 300-strong mob in the town of Majar al Kabir.

By the end of his tour Gaz was estimated to have saved the lives of hundreds of British soldiers and was subsequently awarded the George Medal. By 2008 he was in Helmand, one of only two bomb-disposal experts who could be spared to work alongside soldiers fighting in the most mined country on earth. In April of that year Gaz was deployed to the province as a member of the Joint Force Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) Group team. A month later he had obtained almost celebrity status after defusing eight IEDs in six hours.

The operation began on 9 May, when a Danish vehicle patrol approached a track junction in the Upper Gereshk Valley in central Helmand. It was a classic vulnerable point, or VP, an ideal location for the Taliban to plant one or more IEDs. At the top of the junction, on a ridge line overlooking the valley, was a position which had been used many times before by the Danish troops to monitor movement in the notorious Green Zone. A fertile plain bordering the Helmand River, the Green Zone was where the Taliban held sway. It was ‘Terry’s Turf,’ Gaz said, ‘Terry Taliban’ being a nickname for the insurgents.

The patrol stopped short of the crossroads and two British soldiers from 51 Squadron Royal Engineers, who were accompanying the Danes, began to scan the area. The two British engineers knew that in all likelihood the Taliban had probably buried at least one IED and, using their standard-issue Vallon mine detectors, the pair began searching the area. Moving forward in slow, measured steps, the two young sappers began swinging the detectors from left to right.

Within minutes one of the alarms screamed, signalling the presence of a suspect device. The Royal Engineer knelt down, pulled out a household paintbrush – a vital piece of equipment for every soldier in Helmand – from the front of his body armour, and gently began to brush away dust from the area where the detector had gone off. Within a few minutes the tell-tale shape of an IED pressure plate emerged. The device was marked and the two soldiers moved, one to each side of the track. Minutes later the alarm sounded again. Over the next two hours a total of eight booby-traps were found in a 75-metre radius. It was the largest multiple-IED site ever seen in Helmand.

Back in Camp Bastion, while Gaz was tucking into a pot noodle, his favourite snack, and watching the TV, a ‘ten-liner’ requesting an IED operator suddenly popped up on a computer screen in the operations room of the Joint Force EOD Group. The ten-liner is so named because it reveals ten lines of information about an IED: date, grid reference (location), description, activity prior to find, rendezvous location and approach, incident commander, tactical situation, threat assessment, initial request, requested priority (immediate, pre-explosion, post explosion, urgent, minor, routine, no threat).

Gaz and his search team were on HRF standby and at a drop of a hat they could deploy to anywhere in Helmand to defuse IEDs armed with only the information contained within the ten-liner. And on the morning of 9 May 2008 Gaz was called to the ops room, where Major Wayne Davidson, the officer commanding the EOD squadron, told him he had a task. ‘Sounds relatively straightforward,’ were the major’s parting words as Gaz went to brief his team. The ten-liner stated that there were one or more pressure-plate IEDs in a vulnerable point in the Gereshk Valley.

Within ten minutes Gaz’s team, which consisted of his No. 2, or second in command, the electronic counter-measures (ECM) operator and the infantry escort, the last basically his bodyguard, were ready to move. A few moments later the REST and the RESA had assembled in the briefing tent.

‘This should be interesting,’ Gaz said, then explained the situation. ‘We’ve got multiple IEDs in an area which looks like an overwatch site into the Green Zone. Chances are it’s been used by ISAF before and a pattern has been set. We’ll learn more when we arrive. Questions?’ There were none – everyone knew the score. ‘Good – let’s go.’

Within forty minutes Gaz, his team and the search team were airborne, heading for the IED site in a Chinook helicopter.

Even before leaving the safety of Camp Bastion, Gaz knew the ‘bomb suit’ – an all-encompassing piece of body armour designed to protect ATOs from the effects of an explosion – was not an option. The bomb suit weighs almost 50 kg and the temperature was already 45°C. He knew that he was unlikely to last more than twenty minutes inside it. Besides, a bomb suit is really designed to protect the operator when either walking to or away from the bomb. Gaz took his chances; it was a calculated risk but one which he believed favoured him.

‘By the time I got to work,’ he explained later, ‘the wider area had been cleared by the search team and the area was secured. An incident control point had been cleared and I was happy. I moved forward, took a moment to gather myself, and then began to work methodically through the area. I have been an ATO for a long time and worked in some pretty nasty environments, but I had never encountered nothing like that before. It was pretty tense.’

Gaz spent hours on his hands and knees, his face just inches away from the IEDS. Had any one of them exploded, he would have been killed instantly.

It was the same routine for each bomb. Walk down the cleared lane, locate the device with the hand-held metal detector, and try to isolate the device from the power supply. Operators must always be aware of the potential for other threats in the area. There have been occasions where another device has been placed to target the operator, such as a so-called command IED, which could be something as simple as a hand grenade with a piece of wire or string tied to the ring pull at the end of which is an insurgent waiting for the right time to strike.

This is the most risky period for any IED operator. Once they ‘go down the road’ or ‘take the long walk’ to the bomb, they are on their own and effectively isolated – and make a very inviting target. Everyone else in the team, including supporting troops, must be outside the blast radius.

‘It was 11 a.m. and it was getting pretty hot,’ Gaz explained. ‘I wanted to save as many of the devices as possible so that we could extract the maximum amount of forensic information.’ Just when he thought he was finished, he discovered another IED. But this time it was attached to a command wire, which can either be pulled to initiate the explosion or linked to a power source such as a battery and detonated electronically.

Gaz was stunned. ‘At that stage I didn’t know whether I was being watched by the Taliban who were waiting for me to get close to the device. It was a very sobering feeling. You’re there staring at something, knowing that it could go bang at any moment and that would be it: “game over”.’ But Gaz pushed on and successfully disabled the command IED. ‘I don’t know if I was being watched and the Taliban just decided not to detonate it. But I think it was there to catch out an IED operator. Maybe I was just lucky that day, and that suits me just fine.’

By early evening Gaz had finally completed the mission. He was physically and mentally shattered, dehydrated, his face red and sore after hours in the intense desert sun. It was only when he returned to the incident control point (ICP) for the final time that the fatigue hit him like a left hook. ‘I eventually finished at 6 p.m. I was out there for seven hours but to be honest I didn’t really notice the heat because I was so focused on the task. It was only when I got back into the ICP and it was time to return to Bastion that I realized I was knackered. My arms and legs felt as though they were made from lead and I had a thumping headache.’

But it was a successful mission. Every IED operator wants to recover a device intact so that it can be forensically tested. At this stage, obtaining forensic information left on the device during its manufacture was still in its infancy, but within two years this skill would become key to defeating the bombers.

A smile spread across Gaz’s face as he continued, ‘I managed to disrupt all eight IEDs and all of the forensic information was recovered. That is absolutely vital. We need to know who is making these bombs and we can get a lot of that from the equipment. It was exactly the same as with the IRA. So if I can recover a device and we can get some forensic, then gleaming [soldier slang for brilliant or great], and I sleep well.’

Two months earlier Gaz had been called to deal with a roadside bomb which was blocking a convoy route, leaving large numbers of troops stationary and vulnerable in hostile territory. Wherever possible the Taliban will try to place their fighters in positions close to where they have planted IEDs so that they can follow up a successful detonation with an ambush.

Gaz, knowing the risks and the need for speed, worked solidly for twenty-four hours and discovered eleven devices. One of the bombs was attached to a command wire, which the Taliban attempted to initiate as he walked towards it. Gaz survived only because the device failed to detonate properly. Despite knowing that the Taliban were clearly watching him, he continued working until the entire area was made safe.

‘It was a tough job but in situations like that you just have to be methodical, keep a clear head, and trust your own judgement. I might be the person who goes in to disrupt the IEDs but it’s a real team effort. You have to have total confidence in your search team – and everyone shares the same risk.’

Sitting in the ops room in Camp Bastion, Gaz explained to me how the Taliban were beginning to change their tactics and how he believed the war in Afghanistan would change because the insurgents couldn’t win using conventional tactics.

As I sat sipping a cup of tea in the cool of the air-conditioned room, Gaz disappeared for a few minutes before re-emerging with a large plastic bag. ‘This is an IED,’ he said, holding it up for me to see like an angler with a prized catch. ‘I defused this one and brought it back a few weeks ago,’ he told me with a beaming smile. Before me was a man in his element, but it was clear that Gaz really had no concept at how extraordinary he was. Even those around him, IED operators more senior and experienced, seemed to be in awe.

‘This is the pressure plate,’ he said as he pulled what looked like a shallow rectangular wooden box wrapped in plastic torn from a dirty bag. ‘This is basically a large switch. You have a power source connected to these two pieces of metal and to a detonator. Step on this and the whole thing goes bang – it’s that simple, but it works and it’s deadly.’

The pressure-plate IED’s design is frighteningly simple. Inside the wooden case, which is about 40 cm long, 8 cm wide and 5 cm high, are two rusty saw blades about 15 cm long. The idea is that when pressure is applied to the box, the blades touch, the electric circuit is completed, and the device explodes.

I’m stunned. ‘Is that it?’

Gaz nods, smiling.

‘What’s the explosive composed of?’ I ask.

‘Anything Terry can get his hands on. Mortar rounds, artillery shells, land mines. This place has been at war for thirty-odd years, so there’s a lot of stuff lying around – and if they can’t find any explosive they’ll make their own.’

What’s it like being an IED operator? I ask Gaz. ‘Bomb disposal – it’s the best job in the world,’ he replies. ‘I wanted to do it from the moment I joined up. I love the challenge: when you go down the road it’s all down to you – your wits against theirs – and providing you stick to your training and don’t become complacent you should be OK. The Taliban are always developing their tactics, so we need to make sure we are really on the ball. I’m never nervous when I’m on a job, but I’m never complacent either.’

As we chat away in the ops room, leaning on a table which also doubles as a huge map board, Gaz tells me about an incident which even he admits was a little close for comfort.

Members of 2 Para based in the area of the Kajaki Dam, in the north of Helmand, had discovered an IED on a track leading to their base. As normal, a ten-liner was sent out by the troops and Gaz’s team were dispatched to the scene.

‘It was a routine job – sort of thing I’d done many times before,’ he said, lifting his feet onto the end of the bench. ‘I went through all the normal drills, making sure everything was secure, and so I set about trying to render the device safe. I always work in the prone position – lying down. I find it more comfortable and you don’t present too much of an easy target to the Taliban. I was working away trying to isolate the power source. The device was different to others I had seen. In this case the trigger was an everyday clothes peg with two metal contacts fixed to the closing parts of the peg. The peg was being held open by a piece of rubber wrapped around the opposite end. I thought, I haven’t seen that before – that’s quite clever. While the contacts were held apart the device was safe but it was also connected to a power source, so it had to be isolated as well.’

As Gaz set about working on the device, he noticed out of the corner of his eye that the rubber started to move backwards along the peg. He had less than a second to react. Just before the rubber clip holding the arms of the peg apart snapped, he pushed his finger between the contacts, stopping them from snapping shut and detonating the bomb. With his other hand he pulled out a pair of pliers from the front of his body armour and cut the wiring to make the bomb safe.

‘I saw the ends of the peg moving,’ Gaz said. ‘I didn’t have time to think. I had to act straight away, so I jammed my fingers between the two contacts. I had to make an assessment that there wasn’t a secondary circuit. Then there was no other option but to cut the wires manually. Even for me that was a bit of a close shave.’

The device was wired to an 82 mm mortar and a 107 mm Chinese-made rocket: enough explosive to wipe out a dozen men. Had the peg closed Gaz would have been blown to pieces.

Facing death was part of every IED operator’s daily routine, yet the stress associated with working in Helmand in 2008 left Gaz unfazed. Just before I left him in the ops room, I asked Gaz if he ever worried about being killed. ‘It never enters my mind,’ he replied. ‘You can’t do this job and worry about getting killed.’

On 10 September 2008, less than a week before he was due to fly home to his family, Gaz was killed while trying to defuse an IED on a routine mission in Musa Qala. He was awarded a posthumous Bar to his George Medal on 4 March 2009.

Gaz was the first ATO to be killed in Afghanistan, and everyone who worked in bomb disposal knew from that moment on that his death wouldn’t be the last.

***

I awake, drunk with fatigue, to an announcement over the PA system: ‘Op Minimise is now in force.’ Operation Minimise is launched every time a soldier is killed or seriously wounded. When it’s in force all connections to the outside world – e-mails and phone calls – are suspended until twenty-four hours after the next of kin have been informed. There was a time, when the mission in Helmand was still new, when the launching of Minimise would temporarily silence laughter in the canteens and prompt soldiers to speak in hushed tones. Not any more. Today in Helmand violent and sudden death is a reality of life, and such announcements appear to barely register with the troops.

Stepping out of the large tent, I am greeted by a cloudless sky and the distant but distinctive ‘wokka-wokka’ engine tune played by an RAF Chinook landing on the flight line. Camp Bastion is now a fully-fledged multi-national base. It probably boasts a high ranking on the list of the world’s fastest-growing towns. In 2006, when the soldiers from the Royal Engineers began turning raw desert into a military base, it probably housed just 2,000 troops. Since then it has grown tenfold, although I doubt anyone really knows how many troops are actually based inside at any particular time. It now comprises Camp Bastion 1 and Camp Bastion 2, and the US Marines have grafted their own base, Camp Leatherneck, onto one side.

Bastion is richly endowed with creature comforts. There is Pizza Hut, a Chinese and an Indian takeaway, NAAFI and foreign equivalents, and the American PX store, which sells everything the modern fighting soldier needs. Soldiers with time on their hands can go to the gym, play computer games, jog in complete safety around the camp perimeter, or watch a premiership football match courtesy of the British Forces Broadcasting Service. The Danish battlegroup, which also has a headquarters in Bastion, put on a rock concert. There is even talk that the US Marines are planning to build a swimming pool to increase the comfort of those serving during the summer in Helmand, where temperatures can reach up to 50°.

Soldiers being soldiers, this has led to relations between male and female troops, and in 2009 at least ten British servicewomen fell pregnant and had to be sent home. Numerous canteens each disgorge hundreds of meals every day. British troops even have a choice for breakfast: the continental version for the health-conscious or the ‘full English’ for those who enjoy a heartier start to the day.

The troops live cheek by jowl in air-conditioned tents, sleeping cocooned within individual mosquito nets on camp beds rather oddly described as ‘cots’. The base even has its own police force to ensure that soldiers are properly dressed for meals – open-toed sandals, for example, are forbidden in the dining halls – and those who break the camp speed limit of 15 mph face being issued a speeding ticket by the camp police. The base has also earned the distinction of becoming the UK’s sixth busiest airport – after Heathrow, Gatwick, Edinburgh, Birmingham and Luton – with more than 400 helicopter and aircraft flights every day. It is a far cry from April 2006, when a two-man control team from the RAF’s Tactical Air Traffic Control Unit activated the dirt-track landing strip. Some ninety minutes later the first of hundreds of thousands of flights arrived. Today combat operations, medical evacuations and logistic sustainment flights all operate from what has become a vital military hub.

Discreetly positioned in one area of the base is the headquarters of the CIED Task Force. The operations room is in the same place as the last time I visited, two years ago, when I met Gaz O’Donnell. But there are now more than a dozen IED Disposal, or IEDD, Teams in Helmand, whereas when I interviewed Gaz there were just two. Despite the increase, the IED operators and the RESTs are kept busy all the time, working out beyond the perimeter of Camp Bastion. Most of the teams are deployed to various battlegroup locations in Helmand, while the High Readiness Force – which is composed of a four-man counter-IEDD team, seven-man high-risk REST, and a RESA – is on duty in Camp Bastion, ready at a moment’s notice to fly to anywhere in the province.

The living quarters of the CIED Task Force consist of rows of tents. Above each tent is a board which identifies the team living there. One board reads: ‘IEDD Team 4 – warfare not welfare’ and identifies the ATO as ‘Badger’. Another reads: ‘Team Inferno – First to go, last to know.’ There is little for the soldiers to do in this part of the camp and it is clear that most of the tents are rarely inhabited. Any downtime is usually spent sleeping, preparing for the next operation, or relaxing in the ‘bar’, which, although there is no alcohol on sale, just fizzy drinks and chocolate, has become a gathering point for residents and a place to relax for those passing through.

Another board reveals the location of one of the RESTs and reads: ‘Team Illume – Loves the jobs you hate!’ The sign also reveals that three members of the team are battle casualty replacements – soldiers flown in to replace those who have been killed or injured. It is clear that black humour is one of the life-support systems for anyone involved in IED work, but even though soldiers are flippant about the risks it is an unwritten rule that they never joke about their dead or injured colleagues.

Within a few minutes of arriving at the Task Force Headquarters I meet up with Staff Sergeant Karl Ley – a man who, at 29, has become something of a legend in the IEDD world. Badger, as he prefers to be called – and I’ll explain why shortly – has come to the end of his six-month tour of duty and in that time he has defused 139 Taliban bombs. It’s a record.