Читать книгу A God in Need of Help - Sean Dixon - Страница 6

PLAYWRIGHT’S NOTE

ОглавлениеI spent the first days of September 2009 in Prague, visiting my father-in-law in the city of my marriage. On the tenth of September, I boarded a train heading to Ljubljana, Slovenia, a city just north of the Adriatic Sea, where my wife, Kat, was teaching a class of young documentary filmmakers right on the coast. I changed trains in Salzburg and ended up sharing the first-class car of a vintage train with four elderly women who were unable to discover a single thing about me, despite their curiosity being piqued by the porter, who had told them that my point of origin was Prague. But I didn’t speak German and I didn’t speak Serbo-Croatian.

I also was clueless about how the geography of Europe worked. Despite having a working knowledge of the politics and history of most of its countries, I didn’t know their locations. All I knew was that Ljubljana was south of Prague and that, when I arrived, I was going to be surprisingly close to the city of Venice. That’s what Kat had told me: Ljubljana was close to Venice. Who knew that the countries of the former Yugoslavia were so close to Italy? Not me.

South of Salzburg we hit some crazy beautiful mountains – as if the Rockies had been civilized, at least in places. Other places they were like the Rockies unadorned. I assumed they were the Alps, but I had neglected (as always) to look at a map, so I wasn’t completely sure. And I suppose I didn’t want to ask my companions in the car because I wanted to remain mysterious to them. I kept my nose in a book about the history and culture of Prague, a post–Prague Spring elegy mourning the Soviet rout of a mystical city, written in dense, mournful, poetic prose by a crazy Italian named Angelo Maria Ripellino. I was reading it for the second time.

The mountains got higher and higher and more and more beautiful. I became more and more certain I was in the Alps. I want to say I was certain, to give myself just a little bit of credit, but I really wasn’t. We passed high above a town called Bad Gastein and then just pulled into its train station, as if the station were at ground level and not hovering up there in the clouds.

As we pulled out of the station, where it was sunny and beautiful, I read the following sentence in Ripellino’s book:

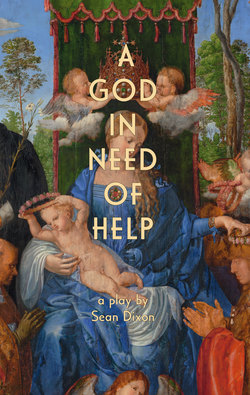

To prevent damage to Das Rosenkranzfest, the Dürer canvas his agents had bought in Venice, the Emperor had the painting carried across the Alps by four powerfully built men.

And then we plunged into a tunnel. When we came out the other end, the mountains were above us and it was raining. A few minutes later, the mountains were below us again.

It was far from ordinary to get my location on the surface of the globe confirmed by an anecdote from an obscure book written in the 1970s about a little-known event that took place in 1606. It made the mountains suddenly very real to me. It made Europe finally concrete to me, the countries all dropping into their proper places. It also made the mountains of four centuries past tangible to me, the labours of four strong Venetian men circa 1606 becoming visceral.

Earlier, I had read another sentence in that book about that same king, Rudolf (who was a shy, pudgy little man who collected art and alchemists, and whose great-grandmother on both his mother’s and his father’s side was Joanna the Mad of Spain). The sentence was a quote from Max Brod (the guy who swore to Kafka on Franz’s deathbed that he’d burn all his works but then published them instead), describing Rudolf as being like ‘a god in need of help.’ I began to conceive a story about a different god, in need of a different kind of help.

Over the course of the next year, I could not find the heart of what I wanted to write about. I successfully imagined many hardships and epiphanies for my four strongmen, got to know them well, but failed to locate my own geographic point – my Alps – to make these characters fall into place. Still, because the moment of inspiration had been so strong, the sense of the men so visceral, the desire remained. I had a reading with some friends in September 2010 and the play fell flat. Still, the desire remained. A few weeks later I gave up writing it, in disgust. I told myself I would return to it in three years.

Then, six months later, while lying on a beach on the east coast of Mexico, the key to my story drifted up into my mind. I had to set the play after the fact, so I could separate my characters and show how radically different were their versions of the events. The play was about belief, and the immutable ways in which we see the world due to our philosophies, our theologies, our simple perceptions. I would never have got to that point of epiphany without that first spark of inspiration in the mountains. The path from the one to the other was my own journey on foot through the Alps.

Sean Dixon

April 2014