Читать книгу James Bond - The Secret History - Sean Egan - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

A CONVOLUTED CREATOR

ОглавлениеWhen in the mid-1960s the James Bond motion-picture franchise began taking the world by storm, a curious aspect of the craze was that it was perceived as part of a modernistic and classless zeitgeist. The swaggering, rule-bucking, increasingly gadget-wielding secret agent of the Bond films was felt to be implicitly in tune with the same reformist trend as the Beatles, Swinging London, the contraceptive pill and civil-rights demonstrations. As the News of the World put it in 1964, Bond was ‘as typical of the age as Beatlemania, juvenile delinquency or teenagers in boots’.

It was curious because Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, was a man who simply could not have been more Establishment. In fact, Fleming’s biographer and onetime colleague John Pearson agrees that he would probably have even hated the term ‘franchise’. Pearson states of Fleming, ‘He was very much what you’d expect from his background.’ That background was quintessentially upper-class.

Ian Lancaster Fleming was born on 28 May 1908. He had an older brother, two younger brothers and a younger half-sister. His father Valentine was a Member of Parliament at a time when that was largely a gentleman’s profession. When his father was killed in action during World War I, his Times obituary was written by no less a figure than Winston Churchill. Ian Fleming attended Eton College, the quintessential English ‘public school’ (by which is meant, private boarding school steeped in arcane tradition) and Sandhurst, the nation’s premium military academy. He also attended Munich University and the University of Geneva. Fleming excelled in languages, being proficient in German, French and Russian. His career in banking thereafter is also part of an archetypal ‘toff’ trajectory of the period, underlined by the fact that his grandfather founded the bank Robert Fleming and Company.

Yet at the same time Fleming was not a clichéd product of his privileged upbringing. His mother pulled him out of both Eton and Sandhurst for his ‘fast’ ways. His stint as a stockbroker was not a success. ‘I must do something that entertains me,’ he told the BBC of the fact that ‘I didn’t get on very well there.’ He was hedonistic in the manner one would expect of someone with far fewer prospects in life, indulging his vices to such a degree that he was cut down shockingly young. Moreover, when, in August 1963, he appeared on the BBC’s Desert Island Discs radio programme, his choice of favourite pieces of music contained no classical works but instead was comprised exclusively of offerings by Édith Piaf, The Ink Spots, Rosemary Clooney and other examples of what most of his class would have dismissed as low culture.

Prior to his stint in banking, Fleming worked for Reuters. He didn’t stay with the famous international news agency longer than three years, but his dissatisfaction was with the money, not the job. He said, ‘I had a wonderful time in Reuters, was a correspondent in Moscow and Berlin and all over the place. And of course I learnt there the straightforward writing style that everybody wants to have if they’re going to write books.’ Fleming eventually returned to journalism, beginning in 1945 a long-term relationship with The Sunday Times. In the half-decade preceding that, he – like so many men of his generation – had found his life and career taking a detour into the service of King and Country.

There have been a hilarious number of docudramas positing Fleming as a man of action during World War II, among them Goldeneye and Spymaker, both subtitled The Secret Life of Ian Fleming. In point of fact, Fleming’s war was axiomatically unheroic and sedentary. He was assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence, John Godfrey. He worked his way up the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve from lieutenant to commander, but never stepped off dry land in that capacity. He would later give James Bond the same rank and background, his creation conceding in the book Thunderball that he had been ‘supercargo’ and ‘a chocolate sailor’. It’s quite true that in his work in Room 39 of the Admiralty – the fabled nerve centre of the Naval Intelligence Division – Fleming was involved in numerous important operations and schemes involving intrigue and cunning. One was a plan that was an accidental precursor to Operation Mincemeat, the famous Allied plot to mislead the enemy with bogus documents planted on a corpse. In 1941, he even wrote the original charter of the Office of Strategic Services, precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency. However, he was almost never allowed to participate in the field, not least because it ran the risk of capture and valuable information being extracted from him by torture.

Nonetheless, Fleming adored his work in Room 39. Pearson says of the Navy, ‘That was one thing he really did worship. That was the only organisation he belonged to which he really enjoyed and respected.’

After the war, Fleming became foreign manager of the Kemsley newspaper group, owned by The Sunday Times. It was a job for which he was qualified on more than one level. Pearson explains, ‘He ran this press agency, a foreign news service called Mercury which he built up in the war as part of the British secret service effort within America with a lot of old secret service friends and so on.’ Some might observe that this sounds as though Fleming was playing a dual role as newspaper employee and intelligence operative. Pearson: ‘There was certainly an element of that.’

Pearson also says, ‘Ultimately it didn’t work because the competition with Reuters was all too tough and Mercury faded. That’s when, to keep him happy, he was given a job at [the gossip column] “Atticus”.’ Fleming would also be given other tasks by the paper, including foreign assignments. In fact, for six years after his first published Bond novel, Fleming continued to work full-time for The Sunday Times.

Not that that day job was particularly onerous. Pearson says Fleming ‘had a very cushy time at The Sunday Times’ because proprietor Lord Kemsley and his wife ‘were extremely fond of him’. Moreover, the fact that Fleming married the ex-wife of Lord Rothermere, proprietor of the Daily Mail, served, says Pearson, to grant Fleming ‘a sort of ex-facie role as almost a member of the newspaper aristocracy within The Sunday Times. He was treated much better than most journalists were. He had longer holidays and so forth.’ Indeed. Fleming negotiated a contract that allowed him to avoid the bitter English winters. He spent his annual two-month leave in Jamaica. He had fallen in love with the Caribbean island – then still a British colony – when he had occasion to visit it during the war. He bought a patch of land with its own private cove and there built a three-bedroom house, which he named Goldeneye, either after one of his wartime operations from 1940 or Carson McCullers’s novel Reflections in a Golden Eye (1941), depending on which story he felt like telling.

Little has been written about Fleming’s journalism down the years, and his newspaper writing has not been the subject of any mainstream anthology. (An omnibus volume titled Talk of the Devil appeared in 2008 but only as part of a deluxe centenary box set of his corpus retailing at a wallet-straining minimum of £2,000.) His travelogue Thrilling Cities (1963) was enjoyable enough, if hardly substantial, while The Diamond Smugglers (1957) was an arid affair, rather like his James Bond books minus the excitement and glamour. Yet Fleming was a highly skilled newspaperman. Pearson would be something of a protégé of Fleming’s at The Sunday Times, at which Fleming secured him a job in the mid-1950s. He describes himself as ‘a sort of leg man’ for Fleming in putting together ‘Atticus’. Fleming – who overhauled a feature that had traded in high-society talk – would suggest stories to Pearson and then deftly hone his submitted copy. Pearson says, ‘I was always amazed at the speed and skill with which he would turn the raw material which I presented him with into very polished journalese.’

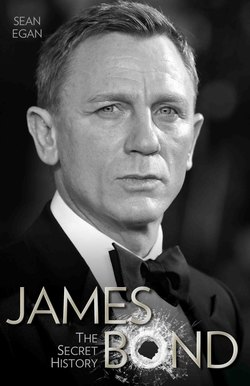

The visual image of Fleming that the wider world would come to have was the one created by the photographs on the flyleaves and back covers of his Bond books. By the time of the appearance of the first of them, he was well past forty. That he would not live to see sixty indicates the life of excess that was made evident in these pictures by his puffy jawline and drooping eyelids. There was a slight air of the ridiculous – even a campness – about the accoutrements with which he usually posed: a bow tie and a cigarette holder. Yet Fleming as a young man was handsome. His oval face was peculiar, but at the same time striking and sensuous. It’s little surprise that he was a ladies’ man.

In 1952, though, he settled down, marrying Ann Charteris. Their relationship long preceded their nuptials. Charteris had been Fleming’s lover during her marriages to both the 3rd Baron O’Neill and 2nd Viscount Rothermere. She had given birth to Fleming’s stillborn daughter during the latter marriage, and it was over her adultery that Rothermere divorced her in 1951. Fleming married her more out of duty than love: she was already pregnant by him again when they wed. Sometimes the viciousness of their relationship was played out on the safe ground of sadomasochistic sex. Other times it was enacted mentally and left deep scars.

This added to Fleming’s pre-existing mental scars, numerous and multi-origined. His melancholy and fatalism was deep-seated. Raymond Benson investigated Fleming’s past and, by extension, psyche when writing The James Bond Bedside Companion (1984). He recalls, ‘Ivar Bryce was his absolutely closest friend – they shared everything – and Ernest Cuneo was his closest American friend. They both would say that Fleming was always just unsatisfied. That he felt like there was something he needed to accomplish that was eluding him.’ Acquaintance Barbara Muir once remarked that ‘Ian always was a death-wish Charlie.’ This suggests far deeper roots for dissatisfaction than living with someone about whom he was ambivalent – namely that during his formative years Fleming felt neither valued nor wanted.

When it is suggested to him that Ian Fleming was a very convoluted person, John Pearson says, ‘You can say that again. He had his demons, as they say … Ian was a classic case of a problematic second son in the shadow of a very, very successful older brother, who was Peter Fleming. Now almost entirely forgotten, very unjustly, but he was a very good prewar travel writer. He was a man of action, very glamorous fellow, highly successful and adored by his racy old mother, Mrs Val Fleming, whereas Ian was always the odd one out and the reprobate and all the rest of it.’

Mrs Val Fleming forced Ian to break off an engagement when he was at university in Geneva, implicitly holding over him the power of disinheritance provided by her late husband’s will. Her hard-heartedness did not stop there. Although Fleming had not excelled academically and had brought a minor level of shame on the family, with his literary creation he outflanked his brother Peter to become by far the most successful of Val Fleming’s brood, yet she would not seem to have been placated by this. Asked if his mother began to respect Ian as he became one of the world’s most successful authors, Pearson says, ‘Don’t think so. I think she became more reconciled to him, but I don’t think that success really impinged upon Mrs Fleming.’

Also unimpressed by Bond was his supposed nearest and dearest. Ann looked down on James Bond novels, jokily dismissing them as ‘pornography’. ‘Annie had this desire to be a bluestocking saloniste,’ says Pearson. ‘She was an intellectual snob and she had a lot of smart followers around her, some of whom were lovers – Hugh Gaitskell was one. A whole group of rather smart intellectuals, writers and so forth, and I think Annie always thought that Ian couldn’t possibly come up to that sort of standard.’

‘That hurt him the most of anything,’ says Benson of Fleming’s wife’s failure to take seriously his literary achievements. ‘One evening he came home and she and some of her literary friends were in the living room and they were reading from his latest Bond novel aloud and laughing.’

In both public and in private correspondence, Fleming would come out with self-deprecating remarks about his work: ‘I’m not in the Shakespeare stakes’; ‘My books tremble on the brink of corn’; Bond was a ‘cardboard booby’. Yet this strikes one as being not so much a genuinely held feeling but an example of getting his retaliation in first, the position automatically lunged for by someone in a lifelong cringe at the expectation of reproach.

Both Fleming’s American agent Naomi Burton and his friend and fellow writer Noël Coward felt he had it in him to write a non-thriller, i.e. literary fiction. From Burton’s point of view, the only reason Fleming did not was that he was afraid of being ridiculed by his wife and her friends.

No fewer than three characters in Fleming’s fiction are afflicted by ‘accidie’, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as ‘Spiritual or mental sloth; apathy’. It seems reasonable to conclude that in fact Fleming had this malaise, and that the malaise was the consequence of a deflated spirit engendered by a lifelong lack of validation.

Pearson recalls of Fleming, ‘He really gave very little of himself away. Although when I worked for him I had three children, including two sons, I don’t think I ever discussed the fact that he had a son too. There was never any interplay of family relations or anything very much.’ Although Pearson suggests this circumspection is partly attributable to his old profession (‘I always felt that he had absorbed an awful lot of spymaster’s mentality from his time in Room 39’), the fact that Fleming did not readily proffer the information of the existence of Caspar – born in 1952 – seems yet another measure of his lack of conviction that anything about him might be of interest to anyone else.

Yet his spiritual flatness was by no means perpetual. Cubby Broccoli, co-producer of the Bond movies, recalled Fleming as a man curious about everything, always anxious to glean knowledge about people and their lives. This hardly chimes with the notion of a man weary of existence, notwithstanding the natural inquisitiveness of writers. Benson offers, ‘He was very melancholic by nature, although he had a very dry wit and a dark humour about him. When he was out and about with his buddies, he was a barrel of laughs and a lot of fun.’

Nor did Fleming exhibit the unpleasantness that is the usual giveaway of self-loathing. ‘Oh, no, not at all,’ says Pearson. ‘I never saw any sign of it whatsoever.’ Politesse comes naturally to the upper classes but Fleming’s civility was not a thin veneer. Pearson: ‘He was in fact very, very kind to me. He got me my first commission to write a book. That was very much typical of Ian.’ Someone who was on far more intimate terms with Fleming was his stepdaughter Fionn Morgan (née O’Neill), daughter of Ann and her first husband Shane. Aged sixteen when her mother married Fleming, she has described him as ‘as much a father to me as a stepfather’ and bristles at criticism of him.

James Bond, though, ultimately seems to be born of Fleming’s unhappiness. He said he wrote the first Bond book to ‘take my mind off the shock of getting married at the age of forty-three’. Although the point he was making was about the upending of what had seemed the natural course of his life – bachelorhood – it’s still a peculiar thing indeed to say about what is usually a cause of great joy and anticipation.

For Pearson, James Bond stemmed from his creator’s fantasy of a happier life. ‘It was very much an essay in the autobiography of dreams,’ he says. ‘I think he used the books, or used Bond, as an alter ego to enjoy himself in ways that he couldn’t in reality.’