Читать книгу Outcasts of the Islands: The Sea Gypsies of South East Asia - Sebastian Hope - Страница 10

One

ОглавлениеI know of no place in the world more conducive to introspection than a cheap hotel room in Asia. I had seen inside a score or so by the time I reached the Malaysia Lodge in Armenian Street. It was May and Madras waited for the monsoon. In the hotel’s dormitory, one night during a power cut, I saw Bartholomew’s map of South East Asia for the first time. I was eighteen.

In other hotel rooms I have puzzled over why that moment made such an impression on me. My first response was overwhelmingly aesthetic; can a serious person reasonably assert that his motive for first visiting a region stemmed from how it looked on a map? Compared to the sub-continental lump of India, so solid, so singular, the form of South East Asia was far more exciting – the rump of Indochina, the bird-necked peninsula, the shards of land enclosing a shallow sea, volcanoes strung across the equator on a fugitive arc. It was the islands especially that drew me. From the massive – Sumatra and Borneo and New Guinea – to the tiniest spots of green, I pored over their features by candlelight.

Thirteen years and hundreds of cheap hotel rooms later, in the spring of 1996, I was in the Malay Archipelago for the fourth time, studying my third copy of Bartholomew’s map spread out on a lumpy bed in Semporna. Its significations had changed for me; it had become a document that recorded part of my personal history.

The real discovery I made on my first trip to Indonesia was the language. I struggled with the alien scripts and elusive tones of the mainland, and progressed no further than ‘hello, how much, thank you’. I could ask, ‘where is …?’ in Urdu or Thai, but I would not understand the answer. I had become illiterate once more. Indonesian Malay was a gift in comparison. There are no tones and it uses Roman letters which are pronounced as they are written (apart from ‘c’ = ‘ch’). That was not the end of the good news. There are no tenses. The verbs do not conjugate. The nouns do not decline. There are neither genders nor agreements. Plural nouns, where the context is ambiguous or the number indefinite, are formed by reduplication of the singular. There were signs of more complex grammar lurking in the use of a number of prefixes and suffixes, but for a beginner the rewards are almost instant. Learn the words for ‘what’ (apa), ‘to want’ (mau) and ‘to drink’ (minum), say them one after another – apa mau minum? – and wonder at the unnecessary grammar and syntax English requires to ask the same question, ‘What do you want to drink?’ In six weeks I had learned enough of the language to make me want to learn more. Approximately 250 million people speak Malay.

By the time of my third visit to Indonesia my Malay was competent. I had become very interested in the country’s tribal peoples after a journey to Siberut Island off the west coast of Sumatra. It is an island some seventy miles long and thirty-five miles wide, covered in the main by rainforest. In the company of a trader in scented wood (who spoke no English) I crossed the island from east to west on foot and by dug-out canoe, stopping at the long houses of the Mentawai clans, a tribe of animist hunter-gatherers. I was entranced by their serene self-sufficiency and their harmonious relationship with the jungle.

On this third visit, I tried to repeat the experience in Sulawesi, where I met disappointment and the Wana people, slash-and-burn farmers who are turning a national park into a patch of weeds. I travelled with the park’s sole warden, Iksan, who was as despondent as I. We were glad to leave the Morowali Reserve, returning to Kolonodale the day before ‘Idu’l-Fitri, the Muslim feast at the end of Ramadan. Despite the fact that neither of us was Muslim we were invited to take part in the celebrations, making a tour of the town with a group of men and being invited to eat in every home. By the time we came to the water village, the houses built on stilts out over the shallows, I wondered how I could eat another thing. We were offered tea and cake in a spacious house made of milled timber belonging to a Bajo family.

I had heard of the Bajo people before, a tribe of semi-nomadic boat-dwelling fishermen to be found in the eastern archipelago. Their name even appeared on the map; the principal port of western Flores is called Labuanbajo, ‘Harbour of the Bajo’. It did not surprise me to find members of the group living in a house in Kolonodale – the Indonesian government has long pursued a policy of settling its traditionally itinerant peoples – but the head of the family told me that he had been born on a boat, and that he had relatives who still pursued the Sea Gypsy way of life. To hear that there were people who practised nomadic hunting and gathering on the sea not far from where I was sitting, refusing more cake, excited an instant desire in me to find these people, to travel with them. I started planning my next visit to the islands before I had even left.

They say Sabah looks like a dog’s head – an observation that can only be made from a map or from space. Semporna was there on the lower jaw. (The rest of Borneo does not look like the rest of a dog.) My final destination, Mabul Island, was too small to feature.

I met Robert Lo, owner of the Sipadan-Mabul Resort, at the World Travel Market in London. He was there on the ‘Sabah – Borneo’s Paradise’ stand to promote his diving operation, to which he always referred as ‘SMART’. My first researches into South East Asia’s boat-dwellers had shown me that their distribution had been much more widespread than I had imagined and that Sabah was one of the places that might still have a completely maritime population. I asked him about Sea Gypsies, out of curiosity as much as anything, but he said, sure, there were lots that anchored near Mabul. ‘I let them use my island to build their boats, to have their weddings, to take their water. Their chief, Panglima Sarani, he’s a good man. I can introduce you.’ He gave me a Sabah Tourism Promotion Corporation brochure advertising the Regatta Lepa Lepa in Semporna, an event which purported to conserve and celebrate ‘one of the exotic culture’[sic], that of the Bajau Laut. My plans had found their focus.

Naturally I had doubts about how authentic such a pageant might be, and they strengthened hourly from the moment I was handed the STPC press-pack in Kota Kinabalu. I would be wearing neither the ‘one of the exotic culture’ T-shirt, nor the Regatta Lepa Lepa baseball cap. Later, on the drive from Tawau to Semporna, I had cause to disbelieve their promotional map of the state.

It was the sort of cartoon map that is handed out at the entrances to theme parks, portraying an enchanted grove brimming with attractions. There were happy climbers on Mt Kinabalu and happy tribespeople waving from their long house and happy divers at Sipadan. Even the wildlife was happy, charismatic mega-fauna peering out from amongst the florets of a forest that covered the whole state. As the minibus left Tawau, I waited for the jungle to start, but it did not; oil-palm plantations spread as far as Semporna.

The Regatta Lepa Lepa was indeed as contrived a piece of hokum as I have ever seen. Not a single Bajau Laut person took part. The lépa-lépa is their traditional houseboat, and there had been several examples on parade for the beauty contest, but none was owned or lived on by a Bajau Laut family. The winning entry had been commissioned by the STPC from a boat-builder on Bum Bum Island. There was no doubting the skill of the wright, nor the authenticity of the craft’s beautiful form, but using the decorated sail as advertising space for his business detracted somewhat from the overall effect. The other events – various boat races, tugs-of-war and catch-the-duck – left me cold.

Corporal Ujan of the Marine Police called me over to their office. I had had a couple of beers with him on my first night in town. It was good to see a familiar face amongst all the uniforms. Security had been ‘beefed up’ for the Regatta. Semporna had been visited twice by raiders from the Philippines within the last month. Ujan had important news.

‘You know the Pala’u man you were looking for?’ I had been told over dinner in Kota Kinabalu with the director of the Bajau Cultural Association, Said Hinayat, that I should not call the Bajau Laut ‘Pala’u’ as it was insulting. Sensibilities in Semporna were not so delicate. ‘That’s him. That’s Panglima Sarani over there.’ Ujan pointed to a jetty not fifty yards away. ‘He’s the old man sitting down mending his fishing net.’

There were two figures on the jetty working on the net. All the doubts and worries that had accumulated along the way on my journey to this point – questions about whether I would be accepted, could communicate, endure – all would be answered in the next few minutes. I stepped onto the decking. Neither looked up at my approach. They were both old, grizzled, and the one facing me was small and looked frail, until I was close enough to see the sinews standing out on his forearms. I thought he must be Sarani – the other had a broad back and powerful shoulders and seemed younger in his body. They were both wearing sleeveless shirts and blue baggy fisherman’s trousers that fasten at the waist like a sarong.

I spoke his name. The man with his back to me turned. He did not seem surprised to see a white man who addressed him in Malay. I squatted down beside him and looked into his weatherbeaten face, his hair stiff with salt, skin almost as dark as his eyes, his lips stained red with betel-juice. I introduced myself. I explained that I was interested in the Bajau Laut and their life at sea. Corporal Ujan and Robert Lo had both mentioned his name. He was going back to Mabul? In the morning. Could I go with him? The success of my journey depended on the answer and I hesitated to ask the question. Sarani showed no hesitation replying ‘Boleh, can.’ He returned my smile, showing his two remaining blackened teeth. We made a rendezvous at the Marine Police post for the following day. I left him to his work and returned to my cheap hotel room.

Packing is like trying to tell fortunes and I picked over my belongings like a soothsayer reading the fall of prophetic bones. I tried to cast my immediate future, to imagine its situations, its practicalities, and provide for them with objects, but I had not even seen one of their modern boats yet. Said Hinayat had told me much about the Bajau in general and he disabused me of the notion that the Bajau Laut still lived on lépa-lépa, but he could not prepare me for what lay ahead, never having spent any time aboard a Sea Gypsy boat himself.

‘Of course “Sea Gypsy” is a misnomer,’ he had said. ‘They are not a Romany people.’ I pointed out that neither were sea-horses horses, but were so called in the vernacular because they resembled a more familiar land animal. ‘But names are important. We Bajau call ourselves the Sama people. So the Bajau Laut, the Sea Bajau, are properly called Sama Mandelaut. They are the only Sama with the tradition of living on boats.’ The other Bajau, House Bajau and Land Bajau, had never been boat-dwellers, although they had arrived in Sabah by sea from their home islands in the Philippines. Their migration started in the eighteenth century, and continues to this day. The Land Bajau are rice-farmers and were among the earliest migrants. They settled inland around Kota Belud and have become known as the Cowboys of the East because of their horsemanship (so say the STPC brochures). The House Bajau live in stilt villages on the coast and islands. They are fishermen, but do not live on their boats. In recent times they have become cultivators of agar-agar seaweed. Many Bajau Laut, he said, had now settled in houses and were integrating with land-dwelling Bajau groups.

Said could not say how many Sama Mandelaut still followed their traditional way of life. The Bajau Cultural Association had other objectives. He had just come back from Zamboanga in the Philippines, scouting locations for the third biannual Conference on Bajau Affairs. There was talk of a peace deal between President Ramos and Nur Misuari of the Moro National Liberation Front, but Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago remained dangerous places. As a politician, Said was immensely gratified by the international attention. He had met the American Clifford Sather, the leading anthropologist in the field, at the first conference in Kota Kinabalu. The second had been in Jakarta, attended by experts from Japan, Europe, Australia and America, one of whom estimated that the Sama-speaking population of the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia might total thirty million. ‘You know they have a Bajau Studies course at Osaka University?’ Our conversation had been punctuated by the incessant ringing of his mobile phone.

I gave up on the packing and went to meet Ujan for a beer. It was an eerie walk through the tropical darkness to the Marine Police post, the streets deserted. The fearfulness that followed the second raid was acting like a curfew. Semporna is much like any other small Malaysian town; the most impressive building is the mosque and the businesses are Chinese-owned. The gold shop targeted by the robbers was no exception. The newspapers were very careful to call them neither pirates nor Filipinos. They were ‘raiders, thought to be nationals of a neighbouring country’. Ujan had been out on patrol at the time, but he told me the story.

The raiders, ten of them, had come from the sea in three plywood speedboats. They were armed with automatic rifles and grenade launchers. They stormed the centre of town, shouting ‘We’ve come for the police!’ The police had killed two of the gang in the previous raid. They fired off a grenade at the police barracks, which failed to explode. The townsfolk did not try to stop them when they turned their attention to the gold shop. They stole £50,000 in gold and cash, and knocked over the register of the shoe shop next door for good measure. The police arrived as they were making their escape and a fire-fight ensued. Two of the robbers were shot dead and a third was captured. The rest escaped with the loot. Two civilians were wounded in the crossfire – an eleven-year-old boy and the driver of a taxi one of the dead robbers had tried to hijack. The two were being taken to hospital in Tawau, the taxi driver accompanied by his pregnant wife, when the ambulance collided with a landcruiser. It was raining hard. The boy and the pregnant wife were killed outright.

One of the robbers had nearly been caught some days later when he tried to steal a fisherman’s canoe. The fisherman was shot in the neck, and his attacker fled. Ujan doubted if they would be caught now. They would have reached the safety either of the ‘Black Areas’ of Darvel Bay (islands like Timbun Mata and Mataking), or else returned to the territorial waters of another country.

Ujan tried to reassure me about the safety of the seas around Mabul and Sipadan. They were patrolled regularly by the Marine Police and the Navy, not least because Indonesia had laid claim to Sipadan. I would be especially safe with Sarani. The Panglima was a respected man, he said, known for his magic powers. ‘It is true: no blade can eat his body, no bullet can enter.’ He too was unable to tell me what to expect. ‘You have arranged to meet him at the post? Then he will be there for sure. He does not make janji Melayu, Malay promises. He is good-hearted.’ And when the following day Sarani did not appear, Ujan’s only comment was ‘Janji Melayu.’

His colleague Corporal Mustafa did not hold out much hope. ‘The market is awake by seven o’clock and the tide was high at eight. If they were staying to buy something, they would have gone to the shop when it opened and left with the tide. They do not like to stay in Semporna because they cannot fish. I think they have gone.’ It was midday. I had been ready since half past seven, but maybe I had not been early enough. Maybe Sarani had changed his mind. Our meeting had seemed too good to be true. I went to look for him in the water market, in the confusion of peoples and languages and products supported above the shallows near the mosque on ironwood piles. I did not find him. The ebbing tide uncovered a beach whose sand was black with effluent. Plastic bags churned in the breaking wavelets. Under the noonday sun, the stench was almost unbearable. The loudspeaker of the mosque jolted into life for the call to prayers.

The television was on when I got back to the Marine Police post, and they had just seen me on it. I had been lurking at the back of the crowd in a news report on the Regatta. Now the sound had been turned down on a sunset shot of the Ka’aba at Mecca; Malay subtitles translating the Arabic prayers ran across the bottom of the screen. Officers sat around and smoked in the afternoon heat. The radio crackled with communications from a boat on patrol. A bald lieutenant arrived on a moped and was surprised to see me standing to attention with the other ranks. Mustafa explained.

‘So you want to stay with the Pala’u? Really? Can you stand it? You can eat cassava? You can stand lice?’ He scratched his shiny pate. I did not have a chance to answer. Sarani appeared in the doorway, looking about nervously. The lieutenant hailed him with mock deference, ‘O, Panglima! Your white son here thought you had gone back to the Philippines.’ Sarani came in once he saw he was amongst friends, but his grey brows remained knitted with puzzlement. He had been stopped that morning in the market by the Field Force. They had wanted to see his identity card, but all he had been able to show them were some letters from local officials. He produced them from his shirt pocket, three typewritten sheets each encapsulated in a plastic bag. He passed them to the lieutenant.

The inefficacy of the documents and the great store Sarani set by them caused the lieutenant some amusement. Sarani could not read them for himself. ‘They say you are a chief. They say you are good-hearted. They say you have been at Mabul a long time.’

‘Since the coconuts were this high.’ Sarani raised a thick hand to the level of his nose.

‘How old are you, O Panglima?’

‘I do not know.’

The lieutenant leant back in his chair. His tone changed to one of concern. ‘Panglima, they do not say you are a Malaysian national. I have told you before you should register your boats with us. Then the Navy will not stop you at sea, and in the market you can show the Field Force the document. Your white son here can paint the numbers on your boat.’

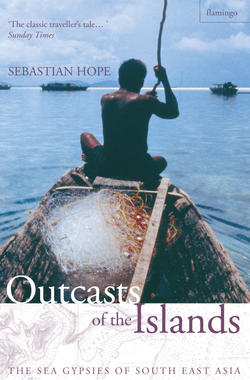

Sarani was putting away his precious letters, and he turned as though noticing me for the first time. ‘Ready?’ he said. ‘The boat is here.’ The change from harmless old man to ship’s captain was instantaneous. We walked out through the back room to the jetty and there, dwarfed by a battleship-grey patrol launch, was Sarani’s boat, wooden and weathered.

It was about thirty-five feet long, its beam six feet, the stern low in the water, the bow steep. The exhaust from the diesel marine had left a black smudge down the white gunwale. An olive-brown tarpaulin had been made into a tented awning amidships. Faces peeped round the edge. The open deck at the bow and the stern was scattered with market goods, a sack of salt, plastic jerrycans, slabs of cassava flour, a tall bunch of plantains, new sarongs. A rusted anchor with a roughly shaped stick as a crossbar sat amongst the purchases. Clothes dried on the tarp. It was not a prepossessing sight.

As I passed my bags down to a young man in jeans on the bow, Sarani stood on the bow rope to pull the boat closer, and ushered me on board, pointing to a space that had been cleared for me under the tarpaulin. The young man walked along the edge of the gunwale outside the awning and reappeared in the stern to drop down into the engine well and start to crank the motor. He wound the flywheel as fast as it would go before flipping the ignition, and the engine coughed into life, blowing sooty smoke rings from the end of the exhaust pipe. Unsilenced, it was deafening, and I couldn’t hear what Ujan and Mus were saying as I looked up at them on the jetty waving goodbye. Sarani cast off.

I was glad for the racket the engine made; it precluded conversation. I did not want to talk, only to observe, as I was being observed. I could feel the eyes of everyone under the tarpaulin were on me, the mother and her three young children, the older woman who was rolling herself a cigarette, Sarani’s white-haired companion from the day before. He touched my arm to gain my attention and mimed smoking one of my cigarettes, before settling down to the reality. I let them get on with scrutinising me and tried not to appear alarming – smiling at the children seemed only to make them cry.

Out in the channel, the sun was fierce. We passed the stilted suburbs of Semporna, single plank walkways their pavements, the open water between buildings their streets. Pump-boats putt-putted in and out of the maze, small two-stroke in-board engines making them sound like mopeds, their riders sitting at the stern with one arm hooked over the plywood side working the paddle that acted as the boat’s rudder. Their flat plywood bottoms bounced across the wake of a trawler coming into port, nets furled around the davits. Less than a mile away was the coast of Bum Bum, with villages dotted amongst the coconut plantations, clusters of rusting roofs surmounted by the shining tin dome of a mosque. The channel turned and broadened, habitation becoming more sparse, and ahead was open sea. Flying fish fled our bow wash.

As we cleared Bum Bum’s southern point, the stilt village that had appeared to be attached to land turned out to be freestanding, planted on pilings over a shallow reef, the houses connected to each other, but to nowhere else. Behind was another island, Omadal, inhabited, and a Bajau Laut anchorage. I scanned the horizon off the port bow where I thought Mabul should be, and I made out a low regular shape looking like the cap of a mushroom, the sides curving down and in on themselves, the top flat – the characteristic shape of a coconut plantation. Sarani moved over to where I sat.

‘That’s Pulau Mabul,’ he shouted, pointing to the shape. We were still travelling south-south-west along the coast, and Mabul was due south, which left me wondering about our course.

‘We are not going that way?’ I pointed straight out towards it.

‘Cannot. There’s coral, you see?’ I had not been looking properly, but now I could see a line of grey rocks that broke the water, the palisade of the Creach Reef running uninterrupted from Bum Bum to the group of three islands we were approaching. ‘Only at the top of the tide can we go that way.’ He looked round at an estuary that bit into the mainland. The river brought brown water and forest leaves out into the channel. The mudflats were uncovered between the mangroves and the water line, and as we passed, a view into the inlet opened up, its banks covered in nipa palm; behind, were hills rising to one thousand feet and the westering sun. Sarani pointed to the flats where egrets stalked. ‘The tide is still coming in. We must go around these islands to reach the deep water.’ He pulled a dirty Tupperware box from under the gunwale, his betel-chewing kit. He peeled off the husk, mottled orange and black, divided the nut and wrapped a portion with some powdered lime in a leaf. He stuffed the package into a metal cylinder which fitted over a wooden baton and mashed the nut and leaf and lime into a paste with what looked like an old chisel bit. He pushed the cylinder down and the baton, acting as a plunger, presented a plug of pan to Sarani’s reddened lips. He packed away the paraphernalia, and went back to scanning the sea, spitting pensively over the side. It is a complicated business, using a masticatory when you haven’t got any teeth.

Manampilik, the last of the three islands, was little more than a steep ridge with a rocky shore. Coconut palms clung to the lower slopes, the higher left to scrub. The sea was glassy in its shelter. There was a swirl at the surface. ‘Turtle,’ said Sarani, and as I looked for it to show again, a fish as thin as an eel, a long-tom, broke from the water ahead of the bow and skipped like a stone once, twice, three, four times, each leap carrying it ten feet. The run ended only after another ten feet of tail-walking. I had never seen anything like it. Sarani laughed at my surprise and said, ‘They taste good.’

We rounded the southern edge of the Creach Reef and passed in deep water between Manampilik and a fourth island, confusingly called Pulau Tiga, ‘Third Island’, a tiny islet, no more than a sand bar, yet covered with stilt houses. It seemed the most unlikely place to site a village, on a strip of sand that looked as though it would wash away in a big sea, with nowhere to grow anything, no fresh water. Was there even any land left at high tide?

‘Oh yes, there is still land,’ said Sarani, ‘you see, they have trees.’ And there were two forlorn papaya plants, whose sparse crown of leaves on a long stem poked up between the roofs, growing in the middle of the village. There was a volleyball net strung between them. It was a surreal touch on a surreal island, a sand bank in the middle of nowhere that quadrupled in size twice a day. Sarani had family connections here. One of his sons had married a girl from the Bajau Laut group whose boats I could see anchored on the southern side of the island. It was my first glimpse of a Bajau Laut community, and it thrilled me.

We turned east-south-east, away from the mainland, and the horizon became immense. The water was indigo, marbled with wind lanes, and moved with a slow rhythm from the south, from the vastness of the Celebes Sea. I could see the tops of the trees on Sipadan to the south-east, the ragged outline of its tiny patch of rain forest, and due east, the peak of Si Amil. Danawan, separated from Si Amil by a narrow strait, and Ligitan, the last island in the group, remained hidden below the horizon. Sailing east from Ligitan there is nothing but water for the next five hundred miles.

We slowed as we approached Mabul’s fringing reef and picked our way through the coral heads, Sarani sitting in the bow on the look-out for snags. The evening sun threw a warm light over the stilt village on the southern shore and long shadows in the grove of palms behind. The shouts of children playing came out across the water. Pump-boats and brightly painted jongkong were returning with the day’s catch, being dragged up the beach between the houses. We made for a long barrack-like building – the school – and nearby a fence ran back into the palms, marking the end of the village, and the beginning of the Sipadan-Mabul Resort. The stilt houses connected to the beach by duck boards were replaced by sun-chairs and thatched umbrellas. The resort’s liveried jongkong and speedboats, all bearing the ‘SMART’ logo of a turtle kitted out in scuba gear, were pulled up on the raked sand. Set back amongst the palms were bungalows with verandas and air-conditioning units. It was a different country.

Sarani expected me to get off here and stay in the resort. He had not completely understood what I wanted to do, and now that I was on the boat I certainly did not want to get off it. ‘You cannot stay on the boat tonight,’ he was adamant, ‘but we will come back for you in the morning. Maybe you can stay in the village.’ We motored around to the other side of the island where the houses were poorer, more ramshackle, and dwarfed by an orderly group of wooden buildings at the end of a long jetty – another resort, the Sipadan Water Village. We nosed back in over the reef, and towards a house whose seaward wall had a doorway where sat an old man with a grizzled crew cut, shirtless, watching our progress. Sarani hailed him, as we cut our engine and glided in, the bow poking into the woven palm-leaf wall. It was agreed. My bags were passed into the house, and Sarani signalled for me to follow them. I clambered in.

‘Until tomorrow?’ I said.

‘Until tomorrow, early.’ I watched him pole the boat around and out towards the deeper water, the sun setting behind the hills on the mainland. I was not completely sure if I would see him again. Meanwhile, for the second time that day, I found myself landed in a strange world where I was the strangest thing in it, feared by the children and stared at by the adults, talked about in a language I did not understand. I sat with my luggage on the other side of the seaward door from the old man. His family hemmed us in, their curious faces catching the last of the light from the western sky. Shadows grew from the back of the hut’s single room. Fishing lines, nets, clothes hung from the palm-thatch walls, baskets from the rafters. Woven pandanus mats and pillows lined one side. I looked around while they looked at me. I looked out at the strands of painted clouds above the silhouette of the mainland, the sea turning grey in the twilight, lights coming on in the resort. Noises of the village relaxing in the dusk, the smoke of cooking fires came from the landward. Wavelets broke on the beach. A breeze rustled in the thatch eaves and set the palm trees soughing. ‘It’s very beautiful,’ I said to the old man in Malay.

‘Jayari cannot speak Malay,’ said Padili, his youngest son, ‘but he can speak English.’ I repeated myself and Jayari followed my gesture at the horizon with his eyes, still uncomprehending. He saw only what he had seen every day of his life, the sea that supported him and his family, the sea that kept them poor. And not a hundred yards away was the Sipadan Water Village, a faux primitif mimicry of the stilt village where he sat, mocking his poverty with its milled boards and varnish, charging per person per night more than his family’s income for a month. The white man thought this view beautiful? I felt ashamed, and added by way of explanation, ‘We do not have this in my country.’

‘Therefore,’ said Jayari, ‘from what country are you coming?’ I was as much surprised by his tone as by a conjunction straight off the bat. He spoke loudly and was so emphatic in his use of English as to be almost threatening. ‘Therefore’ turned out to be his favourite word and he was pinning me down with questions. He held an interrogative grimace after each, and the slight tremble that moved his old body made him look as though he would explode with rage. His mild ‘Ah, yes,’ once I had given an answer, and the occasional grin that betrayed no hint of a tooth, showed his true character. I told him I wanted to stay with Sarani, and he asked: ‘Therefore, what is your purpose in this roaming around on the sea?’

He assumed I would spend the night at the resort, and even started telling Padili to help me with my bags. He was surprised when I stopped him. ‘But you are rich, and there are many people from your country there.’ I told him I had not come so far to meet people from my own country. ‘Therefore, where will you sleep this night? In which village? Please, do not go to the other side. There are many Suluk people there. Therefore, you will sleep here.’ Padili was sent out for Coca-Cola and an oil lamp was lit. Jayari told me that they, and most of the other people on this side of the island, had left the Philippines three years previously to escape Suluk violence. ‘We want to keep our lives, therefore we came here. They attack us with guns. Please do not trust Suluk people. We cannot do these things. We are good Muslims. If we commit bad things, therefore bad things happen to us. How can they commit such things to human beings? Please do not trust Suluk people.’ His head shook as he stared at me, the corners of his eyes clogged with rheum. The households on his side of the island were mostly Bajau. The village on the other side had been there ten years and was a mixture of Suluk and Bajau, with the balance of power tilted towards the Suluk. Robert Lo’s resort took up the whole of the eastern third. Almost everyone on the island, resort-workers included, was an illegal immigrant.

Food was brought, rice and fried fish, and a jug of well-water. I had been wondering what I would do about drinking water and here was the answer. Jayari said he had learnt English from an American teacher at the Notre Dame school in Bongao during the pre-war days of the Philippine Commonwealth. He remembered Mister Henry with fondness, and his home island that he would not see again. ‘Of course we want to go back, but we want to live, therefore we stay here. Please do not trust Suluk people.’

The sleeping mats were being spread for the night. Beside me, with a mat to itself, was a shallow tray, wooden and filled with what looked like ash. Jayari explained they were the ‘remains’ of his grandfathers, carried with him out of Bongao. Every Bajau house had such a place; the seat of Mbo’. I was intrigued by the duality of their belief, Islam and ancestor worship running side by side, but having declared himself a good Muslim Jayari did not want to talk about it.

He was much more interested in the possibility that I was in possession of cough medicine. His cough kept him awake at night. It made his legs weak and he could not go very far before he became breathless and dizzy. He could only smoke one packet of cigarettes a day, and that was upsetting him. ‘Therefore you will give me medicine.’ He had smoked at least five cigarettes while we were talking, flicking the ash through the gaps between the floorboards. I had tried one. They were menthol, but the mint did little to conceal just how strong and rough the tobacco was. The brand was called ‘Fate’, the packet green with a white rectangle front and back on which was written FATE in black letters below a single black feather. I asked how many he usually smoked. ‘Two packets,’ he said, at which his wife laughed and said, ‘Three.’ She had settled on a pillow by Jayari’s leg, but had given no previous sign of understanding our English conversation. ‘They are very strong,’ I said. ‘Can you smoke another brand?’ The younger men smoked Champion menthols, milder, made in Hong Kong and smuggled from the Philippines. ‘I cannot smoke another one, another one makes me cough. I cannot be happy. Therefore, if you pity me, you will give me medicine.’ I only had the remains of the strip of Disprin I had bought for a hangover in Singapore. He looked at them suspiciously, but squirrelled them away in the wooden box where he kept his smokes.

I had not moved from the spot where I first sat down. I needed to stretch my legs. Jayari sent Padili with me to the shore. Night had fallen. The moon had yet to rise. It was probably not the best moment to negotiate the walkway to the beach for the first time. The crossing involved a nice balancing act on rough planks that merely rested on wonky pilings and bent considerably under my weight. What looked deceptively like handrails in the darkness were in fact wobbly racks for hanging nets and clothes and fish. And now that I was halfway, someone was coming in the other direction. We shimmied past each other somehow. It was with relief that I reached the land, although I scuffed my foot against a lump in the sand, and nearly stumbled.

After a day of being scrutinised and interrogated I wanted to be on my own, and walked off down the beach beyond the last stilt hut. I found a log on which to sit and listen to the palms, stargazing and wondering, therefore, what was my purpose in this roaming around on the sea? Sarani would be here in the morning. He would take me fishing as my father had done when I was a boy, and I had a sudden access to memories of summer holidays in the west of Ireland, a time before the disappointments of growing up, the smells of hay and camomile and burning turf, fishing for mackerel with handlines.

Fishing had been an important part of my father’s Devon childhood, and he had passed his father’s love of it on to me. I caught my first fish aged three. Some of my most worry-free hours have been spent on the river bank. Fishing is a stoic teacher and maybe that was why I had sought out a people who fish as a way of life, to learn what it had taught them.