Читать книгу A Bit of Difference - Sefi Atta - Страница 6

ОглавлениеReorientation

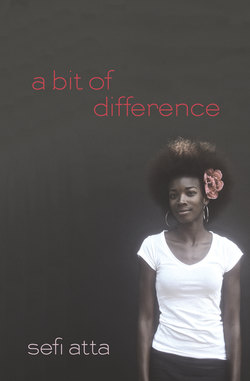

The great ones capture you. This one is illuminated and magnified. It is a photograph of an African woman with desert terrain behind her. She might be Sudanese or Ethiopian. It is hard to tell. Her hair is covered with a yellow scarf and underneath her image is a caption: “I Am Powerful.”

An arriving passenger at the Atlanta airport momentarily obscures the photograph. She has an Afro, silver hoops the size of bangles in her ears and wears a black pin-striped trouser suit. She misses the name of the charity the photograph advertises and considers going back to get another look, but her legs are resistant after her flight from London and her shoulder is numb from the weight of her handbag and laptop.

She was on the plane for nine hours and someone behind her suffered from flatulence. The Ghanaian she sat next to fell silent once she mentioned she was Nigerian. At Immigration, they photographed her face and took prints of her left and right index fingers. She reminded herself of the good reasons why as she waited in the line for visitors, until an Irish man in front of her turned around and said, “This is a load of bollocks.” She only smiled. They might have been on camera and it was safe for him, despite the skull tattoos on his arm.

I am powerful, she thinks. What does that mean? Powerful enough to grab the attention of a passerby, no doubt. She hopes the woman in the photograph was paid more than enough and imagines posters with the prime minister at Number Ten and the president in the Oval Office with the same caption underneath, “I Am Powerful.” The thought makes her wince as she steps off the walkway.

She has heard that America is a racist country. She does not understand why people rarely say this about England. On her previous trips to other cities like New York, DC, and LA, she hasn’t found Americans especially culpable, only more inclined to talk about the state of their race relations. She has also heard Atlanta is a black city, but so far she hasn’t got that impression.

At the carousel, a woman to her right wears cowry shell earrings. The woman’s braids are thick and gray and her dashiki is made of mud cloth. On her other side is a man who is definitely a Chip or a Chuck. He has the khakis and Braves cap to prove it, and the manners. He helps an elderly man who struggles with his luggage, while a Latina, who looks like a college student, refuses to budge and tosses her hair back as if she expects others to admire her. There is a couple with an Asian baby. The baby sticks a finger up her nostril while sucking on her thumb.

It takes her a while to get her luggage and she ends up behind a Nigerian woman whose luggage is singled out for an X-ray before hers is.

“Any garri or egusi?” a customs official asks the woman playfully.

“No,” the woman replies, tucking her chin in, as if she is impressed by his pronunciation.

“Odabo,” the customs official says and waves after he inspects her luggage.

The woman waves back. The camaraderie between them is tantamount to exchanging high fives. Before 9/11 he might have hauled her in for a stomach X-ray.

“Will you step this way, ma’am?” he asks, beckoning.

Walking into the crowd at the arrival lobby makes her eyes sting. She always has this reaction to crowds. It is like watching a bright light, but she has learned to stem the flow of tears before it begins, the same way she slips into a neutral mood when she sees Anne Hirsch holding that piece of paper with her surname, Bello. She approaches Anne and can tell by Anne’s involuntary “Oh,” that she is not quite the person Anne is expecting.

“It’s nice to meet you,” Anne says, shaking her hand.

Anne is wearing contact lenses. Her gray hairs are visible in her side part and the skin on her neck is flushed. She looks concerned, as if she is meeting a terminally ill patient.

“You, too.”

“Now, is it… Dee or Day-ola?”

“Day.”

Anne may well begin to curse and kick and Deola would merely take a step back. It surprises her how naturally this habit of detaching herself from her colleagues comes. They walk outdoors and into the humidity and racket of the ground transportation zone, two women in sensible suits and pumps. Anne waddles—she is pigeon-toed—and Deola strides as if she has been prompted to stand up straight.

“How was your flight?” Anne asks.

“Not bad,” Deola says.

Lying like this is also instinctive. She wouldn’t want to come across as a whiner. A bus roars past, the heat from its exhaust pipes enveloping them.

“Did you get enough sleep?” Anne asks.

“I did, thanks.”

Anne regards her sideways. “I’m sure a few more hours won’t hurt.”

Deola’s face has revealed more than she would like. They head toward the loading bay as Anne suggests she go to her hotel and start her review the next morning.

“If that’s all right with you,” she says.

“Of course,” Anne says.

“Thanks,” Deola says.

She has been working at LINK for three months, following a lackluster stint in a consultancy that specialized in not-for-profit organizations. LINK, an international charity foundation, has a hierarchy, but not one that encourages rivalry as the accountancy firm she trained in did. LINK’s money comes from well-meaning sources and goes out to well-deserving causes. She is the director of internal audit at the London office and Anne is the director of international affairs at the Atlanta office.

Anne leaves her at the loading bay and returns with her car, a cream-colored Toyota Camry. The mat on Deola’s side of the car is clean compared to Anne’s, which is covered with sand. Anne has changed into sandals and her feet are pale, even though it is summer.

“So how is Kate doing?” she asks, as she drives off.

“Kate’s very well,” Deola says. “She’s back at work this week.”

Kate Meade is Anne’s counterpart in the London office. She is pregnant with her second child and was sick with toxoplasmosis.

“It must be catching,” Anne says.

“Toxoplasmosis?”

“No, pregnancy, I mean. When last we spoke she said someone else in London has been on maternity leave. Pamela?”

“Pam Collins.”

“It must have been hard, with all the absences.”

“Pam will be back soon.”

“Yes?”

“Yes. She’s just had her baby.”

Deola could be more forthcoming, but she prefers not to talk about her colleagues. Pam is on maternity leave until the end of the summer. The administrative department has been in a state of backlog. There was some talk about hiring a temp, but Kate decided not to. They had a temp from New Zealand once before and he took too many smoke breaks.

“Ali and I would like to have one,” Anne says. “What did Pam have?”

“Um… a boy, I believe.”

“Ah, a boy. That’s what I would like. Ali wants a girl.”

Deola assumes Anne is married to a Muslim man, which makes her regret her moment of anxiety when, on her way to the bathroom on the plane, she saw a man who looked Arab reading an Arabic-to-English translation dictionary. He was dressed in military khakis. She was not the only passenger giving him furtive looks. Now she wonders if he was working for the US government.

She has reservations about the orange alert the US is on. She has referred to the alerts in general as Banana Republic scare tactics, like Idi Amin or Papa Doc trying to keep people in check with rumors of juju and voodoo, and has compared the Iraq war casualties to Mobutu sacrificing human blood to the gods to ensure his longevity in office. She is in the US to learn how the Atlanta office managed their launch of Africa Beat, an HIV awareness campaign. She and Anne talk about the UK launch, which is a few months away. Her colleagues in Atlanta have not been able to send all their financial records by e-mail or to explain figures via the phone.

Stewart “Stone” Riley is the US spokesman for Africa Beat. His biography reads like a rocker’s creed: born in a small town, formed a group in high school, suffered under commercialization, was crucified by the press, rumored to be dead, rose again in the charts and the rest of it. He claims he is influenced by rhythm and blues. Deola has heard his music and it sounds nothing like the R&B she listened to in the eighties, music with a beat she can dance to. In London, the spokesperson for Africa Beat is Dára, a hip-hop singer. He is Nigerian, but because of the accent over his name and his tendency to drop his H’s, Anne mistakes him for French West African. Deola tells Anne he is Yoruba.

“Dára?” Anne says, stressing the first syllable of his name instead of the last. “Really?”

“His name means ‘beautiful.’ It is short for ‘beautiful child.’”

“That’s appropriate,” Anne says. “He is very beautiful.”

Deola does not know one Nigerian who thinks Dára is beautiful. They say he looks like a bush boy, not to mention his questionable English. It is almost as if they are angry he is accepted overseas for the very traits that embarrass them.

“Do you speak the language, then?” Anne asks, hesitantly.

“Yes.”

“I thought you were British.”

“Me? No.”

She tells Anne she was born in Nigeria and grew up there. She went to school in England in her teens, got her degree from London School of Economics and has since lived and worked in London. She doesn’t say she has a British passport, that she swore allegiance to the Queen to get one and would probably have got down on her knees at the home office and begged had her application been denied.

“You see yourself as Nigerian, then,” Anne says.

“Absolutely,” Deola says.

She has never had any doubts about her identity, though other people have. She has yet to encounter an adequate description of her status overseas. Resident alien is the closest. She definitely does not see herself as British. Perhaps she is a Nigerian expatriate in London.

“Atlanta doesn’t have any programs in Nigeria,” Anne says.

“London doesn’t either.”

“I suppose that’s because you haven’t been approached.”

“Actually.” This slips out with a laugh. “The management team doesn’t trust Nigerians.”

Anne frowns. “Oh, I’m not so sure about that. It’s the government they don’t trust, but it’s a shame to hold NGOs responsible for that. I mean, they are just trying to raise funds for… for these people, who really don’t need to be punished any more than they have been already.”

Deola tells herself she must not say the word “actually” again on this trip. “Actually” will only lead to another moment of frankness, one that might end in antagonism. Nor will she say the words “these people” so long as she works for LINK or ever in her life.

She tells Anne that Kate Meade is considering a couple of programs in Nigeria. One is to prevent malaria in children and the other is for women whose husbands have died from AIDS. The London office funds programs in Kenya, South Africa and other African countries that have a record for being what they call “fiscally reliable.”

“Do you like living in London?” Anne asks.

“I do,” Deola says, after a pause.

“It’s very European these days.”

“It is also very American.”

“How?”

“You know, with hip-hop and the obsession with celebrities.”

Anne shuts her eyes. “Ugh!”

Sincerity like this is safe. As a Nigerian, Deola, too, is given to unnecessary displays of humiliation.

“Do you think you will ever go back to Nigeria?” Anne asks.

Deola finds the question intrusive, but she has asked herself this whenever she can’t decide if what she really needs is a change in location, rather than a new job.

“Eventually,” she says.

z

Atlanta is more traditional and landlocked than she imagined it to be, with its concrete overpasses, greenery and red brick churches. She had envisaged a modern, aquatic city because of the name, which sounds similar to that futuristic series that was on television in the seventies, Man From Atlantis. Downtown, she counts three people who are mentally ill. The common signs are there: unkempt hair, layers of clothing and that irresolute demeanor whether they are crossing the median, rolling a pushcart up Ponce de Leon or standing by a dusty windowpane. It is like London of the Thatcher years.

Her hotel is on Peachtree, some ten minutes away from the Atlanta office. Anne will shuttle her there and back tomorrow. She thanks Anne for giving her a lift from the airport and arranges to meet her in the lobby the next morning. At the reception area, she joins the line and checks into a single room with a queen-sized bed. She inspects the room after putting her suitcase down. She prods and rubs the furniture and unclasps her bra. She needs to buy new underwear. She knows a Nigerian couple in Atlanta she could call, but she finds them enamored with consumerism—cars, houses, shops and credit cards. They brag about living in America, as if they need to make Nigerians elsewhere feel they have lost out.

She turns on the television and switches from one cable station to another. She clicks on one called the Lifetime Movie Network. The film showing is She Woke Up Pregnant and the subtitle reads: “A pregnancy for which she cannot account tears a woman’s family apart.” She turns to another station. Surprisingly, a Nigerian Pentecostal pastor is preaching. He is dressed in a white three-piece suit and his shoes are also white. His hair is gelled back and his skin is bleached.

“Stay with me,” he says, coaxing his congregation. “Stay with me, now. I’m getting there. I’m getting there. Oh, y’all thought I was already there? Y’all thought I was through delivering my message this morning? I haven’t even got started! I haven’t even got started with y’all yet!”

He ends with a wail and his congregation erupts in cheers. A man waves his Bible and a woman bends over and trembles.

Deola smiles. Nigerians are everywhere.

z

Tonight, she dreams she has accidentally murdered Dára and deliberately buried his remains in her backyard and she alone knows the secret. The police are searching for him and the newspaper headlines are about his mysterious disappearance. The newspapers spin around as they do in 1950s black-and-white films until their headlines blur. She wakes up and tosses for hours.

The next morning, she is still sleepy when she meets Anne in the lobby, but she tells Anne she is well rested. Anne grumbles about the price of her Starbucks latte on the way to the office and sips at intervals.

“The problem is, I’m hooked on the stuff. And it’s not as if you can go cold turkey, because the temptation is everywhere.”

“London has been taken over by Starbucks,” Deola says.

She has heard some requests for a latte that are worth recording: “Grand-day capu-chin-know.”

“That’s a shame,” Anne says. “I’ll be there next month and I know I won’t be able to help myself.”

“Isn’t Rio having their launch next month?”

“Yes. I’ll be there for that.”

“Do they have Starbucks over there?”

“I hope not.”

The Atlanta office is also on Peachtree. People in the elevator glare at them as they hurry toward it—the usual disdain inhabitants of cramped spaces have, followed by a general shyness. They all look downward.

The reception wall has the logo of the foundation’s network, two linked forefingers. The office is mostly open-plan space with workstations. Deola meets Susan and Linda, who are also auditors. Susan is a CPA who trained with an accountancy firm and Linda has a banking background.

“Don’t you think she sounds British?” Anne asks them.

“Well,” Susan says, “there’s some Nigerian there.”

There is some Chinese in Susan’s voice. Her thick-rimmed glasses are stylish. Her jacket is too big for her and her slender fingers poke out of her sleeves.

“I think she sounds British,” Anne says.

“She sounds like herself,” Linda says.

Her braids are thin and arranged into a neat donut shape on her crown.

There is a Linda in every office, Deola thinks, who will not waste time showing a newcomer how much her boss annoys her. Why she remains with her boss is understandable. How she thinks she can get away with terrorizing her boss is another matter.

“I should say English,” Anne says. “What does British mean anyway? It could be Irish or Welsh.”

“I don’t think Ireland is part of Great Britain,” Susan says, blinking with each word.

“Scottish, I mean,” Anne says.

“I can’t understand the Glaswegian accent,” Deola says.

“I couldn’t understand a word anyone said to me in Scotland,” Anne says. says.

“They probably wouldn’t understand a word we say over here,” Linda

Deola notices leaflets on “commercial sex workers” and is conscious of being between generations. Old enough to have witnessed some change in what is considered appropriate. Her colleagues walk her through their system and she reverts to her usual formality. They show her invoices, vouchers and printouts. It is not relevant that they are in the business of humanitarianism. There are debits and credits, checks and balances. Someone has to make sure they work and identify fraud risks, then make recommendations to the executive team.

As an audit trainee, she was indifferent to numbers, even after she followed their paper trails to assets and verified their existence. How connected could anyone be to bricks, sticks, vats and plastic parts? Her firm had a client who did PR for the Cannes Film Festival and it was the same experience working for them. With Africa Beat, the statistics on HIV ought to have an impact on her and they do, but only marginally. The numbers in the brochure are in decimals. They represent millions. The fractions are based on national populations. Deola knows the virus afflicts Africa more than any other continent, women more than men and the young more than the old. Her examination of the brochure is cursory. She has seen it before and it is the same whenever she watches the news. Expecting more would be like asking her to bury her head into a pile of dirt and willingly take a deep breath in.

z

Ali is a woman—or a Southern girl, as Anne refers to her. Her name is Alison. Deola doesn’t find out until later in the evening when Anne treats her to dinner at a Brazilian restaurant. Ali is from Biloxi, Mississippi, and she is a florist. Anne is from Buffalo, New York, and she used to be a teacher there. They don’t watch television.

“We haven’t had one for… let’s see… five, six years now,” Anne says. “We read the newspapers and listen to NPR to keep up with what’s going on.”

“I watch too much television,” Deola says.

She chides herself for finding belated clues in Anne’s stubby fingernails as Anne gesticulates, so she brings up the title of the Lifetime Movie Network film.

“I thought, this has got be a joke. She woke up pregnant?”

“The networks in general don’t credit women with any intelligence,” Anne says. “Mothers especially.”

“I can well imagine,” Deola says.

Their table is under what looks like mosquito netting dotted with lights. Behind them is a fire with meat rotating on spits. The waiters wear red scarves around their necks and walk over once in a while with a leg of lamb, pork roast, filet mignon, scallops, shrimp and chicken wrapped in bacon. The bacon is more fatty than Deola is used to.

“But we can’t decide who gets pregnant,” Anne says. “So wouldn’t that be perfect if one of us wakes up and boom?”

Deola has finished eating her salad, but she picks at the remnants of her grilled peppers and mushrooms as the thought of artificial insemination diminishes her appetite. Or perhaps it is the realization that she might one day have to consider the procedure, if she remains single for much longer.

This is an unexpected connection to Anne, but she won’t talk about her own urge to nest, which has preoccupied her lately. Anne might regard what she has to say with anthropological curiosity: the African woman’s perspective.

“There’s always adoption,” she says, wondering if this is appropriate.

“I did think of that,” Anne says. “You get on a plane and go to a country that is war-torn or struggling with an epidemic and see so many orphans, so many of them. But at the end of the day, you have to have the humility to say to yourself, ‘Maybe I am not the person to raise this kid. Maybe America is not the place to raise him or her.’You have to ask yourself these questions.”

“You must,” Deola says, crossing her arms, as if to brace herself for more of Anne’s rectitude.

“It’s that mindset,” Anne says. “Our way is best, everyone else be damned, the world revolves around us. But I think when you travel widely enough, you quickly begin to realize it don’t, don’t you think?”

Deola reaches for her wine glass and almost says the word “actually,” but she stops herself this time. Actually, the tongue jolt. Actually, the herald of assertions. She could insist that America is torn apart by the war and she could easily challenge Anne’s assumption that the rest of the world is incapable of transgressions.

“I expect people in England are more open-minded,” Anne says.

“England? I’m not so sure.”

“I guess it would be more obvious to you living there. But that’s why we are in such a mess over here, and it’s a question of being able to reorient yourself. That’s all it takes.”

“A little reorientation,” Deola says, the rim of her glass between her lips.

“You know?” Anne says. “If there is one thing this job teaches you, it’s that. You can’t get caught up in your own… whatever it is. Not in a world where people starve.”

“No,” Deola murmurs.

It is just as well she hesitated. She finishes her wine; so does Anne. A waiter approaches their table with dessert menus. Anne says she really shouldn’t and opts for a black coffee. Deola has the passion fruit crème brûlée and asks for fresh raspberries on top.