Читать книгу Skin - Sergio del Molino - Страница 8

The Devil Card

ОглавлениеWhen the metamorphosis was just beginning, and the rash nothing but tiny blotches that could just as well have been fleabites, I was living with a witch in Madrid. It was early autumn in 2000, I was 21 years old and, though I’d had dealings with witches before, it was the first time I’d lived with one. She was the friend of a friend. Our friend in common found out that she had an unoccupied bedroom in her flat in Cuatro Caminos and wanted a flatmate to split the costs. What luck, said my friend: I’ve got a friend who’s looking for a room. And she got us together.

I was studying journalism, which is to say I only ever went to university when it was time for an exam, which I would have revised for the previous night using the photocopied notes some very diligent girl had taken down in her convent-school handwriting. The rest of the time I spent in other departments (Philosophy, for example, reading French novels from the library) or in the National Film Library, unsystematically guzzling down the work of all the classic directors. The witch was in the same department as me, but studying PR and advertising, and attended classes daily, sometimes taking immaculately clear notes in convent-school handwriting. We were enrolled in the same building, but various worlds separated us. I had chosen indigence and indolence; she dreamed of offices in glass towers, cocaine and prize ceremonies at Cannes; for me it was the bar life, the low life, smoking the occasional joint (though I never inhaled) and letting my hair grow long.

In the world of PR execs she was aiming for, if she wanted to fit in she would need to tone down the witchy personality, but only to an extent. Getting rid of the nastiest aspects – like the unsightly eczema and the blue saliva – was enough. Otherwise, a touch of the esoteric always goes down well in high society. It needs framing in an elegant, Ibiza-dwelling sort of way, like the kind of attire – just something I threw on – that only looks good on the rich and tanned. A witch can be a good publicist, so long as she avoids getting sucked into some Getafe dive where she’s obliged to wear a turban and read the coffee grounds for slot-machine-addicted housewives convinced (always correctly) that their husbands are cheating on them with the woman, or women, next door. Patricia, which was my witch’s name, was learning to modulate her esoteric register in order to be able to fit in at a summer party in Marbella, which was why she warned me against any indulgence in the mass-market side of witchcraft. For example, she forbade me from going into La Milagrosa, the santería shop below our flat, where they sold black candles in the shape of gigantic penises, which I used to find hilarious.

Don’t play around with that, she would say. Promise me you won’t buy anything from that place, they’re bad people, and they do black magic. I’m warning you.

And that magic was black, but as in the colour of its skin. What really bothered her about La Milagrosa was that its client base came from the Caribbean and from illiteracy, and a hip publicist wasn’t going to win a contract with Coca Cola if she showed up singing African mumbo jumbo with voodoo beads around her neck. Her magic always had to be the refined, white, European kind. Or Asian at best, and India trumped China. Racism is rife among people involved in esoteric practices, and I found it infuriating, because I really wanted one of those gigantic penises but, out of respect for my racist witch, I never bought one.

Patricia had a beautiful set of tarot cards, which only she was allowed to touch – it will de-magnetise, she said, you mustn’t contaminate it with your energy – and which had been designed by a White Russian in goodness knows which decade and which country. That was why the devil card had Stalin’s face. When I was home alone, I defied her prohibition, opened the drawer containing the cards, took them out of the pouch she kept them in, and shuffled and ran my fingers over them. It was a brightly coloured set, Russian art-like, with pictures that resembled byzantine icons, all fierce eyes and unflinching looks. I greatly enjoyed handling them, and it was a real let-down that Patricia never noticed I had been doing so. She never registered my having de-magnetised or contaminated them with my energy.

Read my cards, would you, Patricia? I said in a moment when I felt my faith growing weak and wished to renew my vows.

Patricia was lazing around. She was perfectly happy watching the television and had no desire to clear the coffee table in the living room, which was forever covered in glasses and bottles.

Come on, Patri, come on my girl. Read my cards.

Puffing out her cheeks, she grudgingly lifted herself off the sofa, turned the TV off and got the cards out of the drawer.

You tidy up this shithole for me, she said. You’ll get a terrible reading with all these dirty glasses around.

She shuffled, and told me to cut the pack without touching the backs of the cards, only the sides. She then set about lining them up in rows, laying one at a time as though this was solitaire, and murmuring to herself the while. With her, it was never a case of good or bad cards: Patricia said all of that meant nothing, the cards were neither good nor bad, nor did they predict the future. They were a projection of your personality. She always played down the magical aspect, reducing everything to a question of natural energies and biochemistry. It was not the magic objects that had power over us, but the other way around: our bodies – casings for the spirit – left imprints that she was able to read, bringing her into an understanding, in a few short minutes, of the person across from her, the kind of understanding that those of us who aren’t witches take years of intimacy, cohabitation and nocturnal conversations to achieve. The cards were a diagnosis of the present, never a future prediction.

And an indulgent diagnosis, obviously. Patricia portrayed me in a way that I would like. Or in a way she thought I would like: you’re impulsive, you have a real inner strength; don’t overlook your rational side, seeing how sentimental you tend to be, which is necessary in the right moment, but can also be debilitating for you. Plus, wow, I see a very charged sexual energy. If you run into someone else bursting with it like you are, it’s going to be a hell of a meeting. But make sure they don’t dominate you.

Easy, Patri, I think I can dominate myself. You’re not going to have to put a bolt on your door tonight.

Idiot. Shall I carry on?

Carry on, carry on, please.

And she went on laying cards, until Stalin came out.

The devil!, I shrieked. Oh no.

I’ve told you a thousand times, the devil isn’t bad. And particularly in your case.

How can it not be bad, it’s Stalin! Look at that scowl, that moustache! He’s very bad. Don’t sugarcoat it for me, I can take whatever it is. Tell me what it means.

There isn’t one single meaning. This isn’t a science, it’s perception, art, interpretation. Within this spread, it’s alerting you to your instincts, it’s saying they might betray you. Look, I’ve drawn it upside down.

That’s bad.

The cards next to it tell us it’s to do with health. Have you noticed anything strange recently? Any pain, anything bothering you?

Nothing at all.

And those blotches on your arm?

Just a rash.

It’s been there for quite a few days.

Does the devil upside-down mean ill health?

It’s a way of warning you that something’s incubating, some danger for the body, almost always sexual. You haven’t had unprotected sex, have you?

Oh, bugger Stalin.

I only offer warnings. You men are so carefree – plus you in particular go to bed with every madwoman around. So, I don’t believe you for a second.

I’m telling you, no. Neither protected nor unprotected. I’ve been spending my every waking minute at the National Film Library these last few weeks. I could have picked something up there. They say there are fleas.

If you bring fleas into the flat, I’ll throw you down the stairs. And keep an eye on those blotches, they don’t look like a normal rash to me. Do they itch?

A bit.

You mustn’t scratch them.

I won’t scratch, Comrade Stalin.

You’re doing it right now.

I’m a dissident, that’s the thing.

And an imbecile. Now, leave me be for a bit, I’m going to meditate in my room. I’ve got a statistics exam tomorrow. You, get yourself a doctor’s appointment.

She shut herself in with her supermarket candles (never from La Milagrosa) and the bag of bog-standard sea salt with which she made a protective circle on the ground, and I didn’t see her again until the following day. I never bothered her when she entered that state, not so much out of respect as because those rituals struck me as a piece of overacting that jeopardised her metamorphosis into a cosmopolitan, liberal kind of witch. It pained me to see her plunge into an esotericism so down-at-heel.

I went on scratching those nanoscopic blotches – the colour of which varied from red to light pink according to the light, the time of day or how hydrated or dry my skin was – until they bled. Then I saw that they weren’t, as I initially thought, insect bites or spots, but patches of flaky skin. My nails had broken through the tiny plaques, not dissimilar to scabs, bringing a small amount of blood to the surface. Very thick little blobs of blood that dried instantly, forming a horrible black scab that I picked off as well, making it bleed once more. Scratching made it worse, but there’s not a person in the world who can resist.

My head was also itching. I’d had light dandruff for a while, which, given my long hair, was very annoying but until that moment I’d never connected to the blotches on my arm. Structurally, the flaky skin was the same as dandruff. They were the same thing. Psoriasis. Dermatitis. An infection, I thought. I would like to say that I didn’t worry about it in the slightest, but that inverted devil had planted certain thoughts in my head. Like all true believers, I made a great effort to appear sceptical and joked with Patricia as she read my cards, to the point that my not taking it seriously made her angry. But obviously I did take it seriously. That was why I laughed.

I eased open the drawer containing the tarot set. It was the first time I’d taken it out when she was at home. Please, I said, don’t let her need the toilet or a drink of water, but Patricia must have entered genuine trances because I never once saw her come out of her room when she was meditating. I looked for the devil card, which when I found it was once again upside down. I turned it over and regarded it for a few moments. It was beautiful.

Tarot cards remind me of illuminated manuscripts. They contain all the world’s ingenuousness and worldliness at the same time, that so very naïve yet consoling idea that things of complexity, even unknowable things, can be expressed in a cryptic symbol. The major arcana have cabbalistic meanings. The devil corresponds with the letter samekh, which according to Patricia, refers to the shell that surrounds us. It is invoked in order to liberate us from the unpredictability of the future, and to enable our personality to develop beyond the limits of our outer casing. The devil and samekh alike want us to peel away our skin, to burst at the seams in order to move unguardedly closer to the Unnameable. Samekh is a potato peeler that removes our skin in order to reveal the ego, but all I saw was a very angry Stalin looking out at me, a death-sentence-signing face, and I had no idea how that could help me find God, whom I’d never had any great desire to meet anyway.

It wasn’t the Soviet Terror, or the Cabala, or the major arcana that were making my stomach crawl. The suggestion had come a number of days before, when Patricia had read my palm. We’d had a few drinks together in the living room and it had grown late. We were tired, but neither of us felt like going to sleep and we drew the evening out providing one another with increasingly unspeaking, absurd company. My hand ended up in hers by accident, and then she couldn’t avoid reading my palm. I observed her very closely. She ran her fingertip over the lines on my palm, barely skimming the surface, and asked if I wanted to know.

I always want to know, Patri.

I won’t say anything about the other lines, which are normal, but the life one is strange, I’ve never seen one like it.

Why?

The normal thing is for it to be long and not very pronounced, but yours is very short, do you see? And very deep. It looks like a wound, something artificial. It’s deeper towards the end, but, unlike the rest of the lines, it doesn’t grow thinner. Look, it ends here, abruptly.

And what does that mean?

Well, you already know that the lines change in accordance with changes in our life. This is not your fate. It’s a portrait of your present moment, of the future that will befall you if you fail to wake up to your situation.

Fine, fine, but tell me what it means.

But I just told you: that you will have a short life, that it’s going to end abruptly. In an accident, maybe, or in a terminal illness.

I won’t suffer, then.

I don’t see that. Possibly. But what this shows is a short life that ends suddenly.

Well, you ought to make the most of me while I’m still around.

Look, matey, it’s pretty late to be starting with the whole sexual tension thing. Late in the evening, and in our relationship. Plus, I’ve got my period.

Witches don’t have periods.

I don’t know about the others, but this witch is going to take a Nolotil and get some sleep.

Before I fell asleep on the sofa, in front of the late-night shopping channel adverts, I convinced myself that I wasn’t going to make it to thirty, which to me seemed not such a bad thing, maybe because from the vantage point of having just turned twenty-one, thirty seemed a long way away, or because the days were dragging by and racking up thousands of longueurs to the point of being consumed by aches and pains and bones twisted out of shape by arthritis seemed an unbearable prospect to me. A quick death, and with any luck a clean one. A quick passing, too quick for very much suffering, with no children around to traumatise or lovers to mourn me. Not only was it more consoling as an idea than anything the tarot could offer, it also confirmed my oldest belief.

I already knew I was going to die young. I had known since I was eight. My parents and I had lived in a holiday-destination village near Valencia – we had moved quite a bit, though not what you could call nomadically – with a beach that would fill up with people from Madrid, and French and Germans, in the summer. Before you heard them speak, you could tell a foreigner by the flabby whiteness of their northern skin, dazzling at a distance. We village children would have had carboniferous tans from the very first sunny days in the spring. By the time the tourists came around, we were all well toasted and had no need of sun cream or parasols. Which was why we ran around on the beach from sunrise to sunset without our parents batting an eyelid.

Nowadays I envy my parents, I who cannot take my eye off my son for a second when we’re on the beach and won’t let him out of my sight or run off if I don’t know who he’s with. Compared with me, he’s grown up in a bubble, or something zoo-like, but, in exchange for my paranoid vigilance, I offer him a world without fears. Not only does he believe that witches don’t egg-siss, he also has no conception of the everyday evil of the paedophile, the kidnapper or the man who laces sweeties with sedatives. He doesn’t need to know about any of that, because his mother and I are always there to ward off such things. My parents didn’t watch me every second of the day. Their approach was to load me up with a repertoire of horror stories far more effective than the police force. On the prompting of these tales, my friends and I were wary of any adult who happened to come prowling around. If a car slowed to a halt next to where we were playing in one of the irrigation ditches, we’d all just run away before anybody could even get out. If the door-to-door carpet salesman tried to cosy up to us, we’d throw sand at him and be gone in a flash. These were the easily preventable dangers, the ones we could get out of at a sprint, but there were others that were far more intangible and unpredictable. The worst of all being needles.

The most popular horror story in 1987 was AIDS. In the village there was a prominent community of punks who used to get together with their mohicans and their dogs in the same square where families gathered for a traditional horchata con fartons. Keep away from them, my mother would say. Those so-and-sos – according to her – went to the beach every night to shoot up, and they would bury their syringes in the sand with the needles pointing up. So that anyone going barefoot on the beach the next morning would step on them, and be infected. We could run away from kidnappers, but how to evade such tricks? I was apprehensive every time I planted a foot in the sand. Even when we were running around and playing football, I always watched where I was about to step.

It was late already and we had been given the going-home ultimatum. Perhaps this was why my guard was down. I went over to the showers to wash the salt and sand off, when I felt a stabbing pain in the sole of my right foot. Lifting it up to look, I saw droplets of blood coming from a pinprick in my instep. I didn’t go digging around in the sand; I knew perfectly well what I’d stepped on. I went the rest of the way to the shower on tiptoes and held the sole of my foot under the running water until the bleeding stopped. Really, there were barely three drops of blood, but it hurt like a stake had been driven through me.

You’re limping, what’s wrong? said my mother, handing me my sandals as I put on my t-shirt.

I didn’t answer. I got into the car in silence and didn’t say a word all the way back, or when I was in the shower at home, or putting my pyjamas on, or over the reheated green beans from the previous day, or when I was left alone in my bedroom after the good night, sleep tight.

I turned on the bedside lamp and examined my foot. There, almost in the exact centre of the sole, was the dot: circular and, to anyone who didn’t know what they were looking for, invisible. I turn out the light and slept a peaceful sleep. There was no anguish, no desire to tell anyone about it. I was going to die gaunt and dishevelled, like an actor or a petty thief. There was nothing to be done: I had AIDS.

I resigned myself to not seeing another summer. I packed away my swimming trunks and turned my thoughts to autumn, convinced I would never set foot on a beach again. I put my jumper on believing that I would not be having Christmas dinner that year in my grandfather’s village. I went about saying goodbye silently, secretly, with no feeling of drama, no mise-en-scène. Waiting for death seemed like waiting for any other thing, such as break time at school or a doctor’s appointment.

But months went by, and I just kept on not dying. Another summer came, and then another, and I started to grow stubble, and my voice dropped, and I stopped being a child any longer, and still my heart went on pumping. But neither clocks nor calendars averted my belief in my sentence: death was only being deferred, I hadn’t escaped it. The AIDS virus was lurking somewhere in my body, just waiting for the right thing to spark it. Its belated arrival was because it knew I didn’t care, and it wanted to creep up on me just when I forgot about having stepped on the needle, because death is a lover of tragedy and of mise-en-scène and has no time for woebegone types who neither tremble nor weep nor beg for someone else to be taken in their place.

When Patricia read my palm and described that short, deep life line, I said nothing about the red dot on my right instep. I expected her to divine its presence, for it to shine forth to her mystically, like an agni chakra of the foot, but she was too tired, and she had her period and wanted to take a Nolotil, and no one in that state is going to perceive transcendent things. For all that I insist on the fact that witches aren’t human, all the ones I’ve met are possessed of a humanity that throbs within them just as my own does, and I’ve never been convinced that we can know other people when our own body is distracting us; it’s impossible to heed the pain of others if our own is constantly filling our ears.

Will Stalin see the red dot on my foot, with those Byzantine emperor eyes of his? On that devil card, small demons distract him by tickling his feet: the devil in the tarot always comes accompanied by such imps. Stalin’s knitted brow could be because he can’t scratch the places where the demons are touching him, as I scratched my arm, ripping off the scab, making it bleed again. The severe inscrutability of icons has never seemed like an attribute of power to me, but rather like the expression of the fact that something’s bothering them. It’s possible that Justinian and the awe-inspiring Pantocrators in Venetian churches don’t wish to strike their subjects down with a look, but that they’re doing all they can not to scratch. That Stalin wasn’t judging me, he was simply feeling uncomfortable and wanted to be alone so that he could scratch himself like an animal or go for a bath back at the dacha. Had I looked at the card more closely, I would have discovered a hint of sarcasm in his eyes, that compassionate mockery present in the glances exchanged by all who suffer skin conditions. I still didn’t know I was ill, but Stalin must have; after all, he was one of the major arcana.

Now I do know and I am going to tell my son about it. I will commit to the page these horror stories, which I still cannot play out for him at bedtime because the protagonists in these are monsters that do egg-siss, and that which is real, that which does egg-siss, is not the realm of children. Not because it will frighten them, but because they’re bound to get fed up with it when they cease being children, and everything then exists.

I read him a chapter from a Roald Dahl story every night. We range quite widely in the books we read together, but Dahl is our latest obsession. He has it the same as me: when he gets into a writer, he won’t stop until he’s read their entire body of work. Reading out loud means not only turning the words into sounds, but acting as well. I don’t put on voices to distinguish between the different characters, and I don’t sing the Oompa Loompa song, nor do I stretch out the vowels in an exaggerated way or gesticulate in slow-mo, in the manner of children’s storytellers who take children for people with brain damage. My particular mise-en-scène is far more subtle: at no moment do I cease being myself, and at the same time I am the narrator and all the characters. The metamorphosis comes about through imperceptible modulations in the voice, or so I believe, because I’m not completely clear about the moment in which my son stops hearing me and starts hearing the characters and the narrator.

Dahl has a way of tuning in to the wickedest frequencies in the personalities of children. Those who don’t know children tend to treat them like objects in a museum, things to be preserved in display cases and admired from afar, neither touched nor exposed to the elements; but anyone who dares to smell their breath knows that children can absorb bad things entirely unscathed, things that adults cannot stomach. It is us, the elders, who are afraid, because true fear can only arise out of experience. When confronted with debts we cannot pay, we’re afraid of going hungry. War frightens us because we have seen what it did to our grandparents. We’re terrified of illness, having cried at friends’ funerals. Fear without experience is nothing but a philosophical derangement, which is why children are never truly afraid. In the deepest recesses of every child there is an immaculate darkness, and Dahl knew how to combine words in such a way as to stimulate it. Fear, looked at like this, is funny for the child, but unbearable for the parent.

When I turn off the light and go out of his room, upon transforming back into what I am, I go and shelter in the books Dahl wrote for adults, which, like everything he did not write for children, is full of consolation and hope.

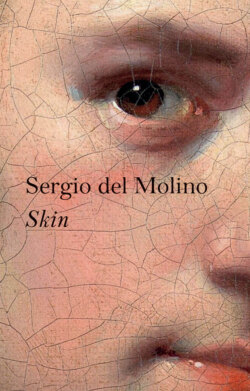

‘Skin’ is one of my favourites of his stories. Drioli, a small-time tattoo artist – I don’t know if there’s such a thing as a big-time tattoo artist – befriends Soutine, a Parisian painter who is just as small-time as him but has just sold his first paintings. To celebrate, they get drunk in the latter’s studio, and the night ends with Drioli offering his back as a canvas. He shows his friend how to do a tattoo, and Soutine paints a masterpiece on his skin. Many years later, Drioli passes an art gallery and is apprised of the fact that his friend, now dead, is a much sought-after artist. He has remained a wastrel, but he has a Soutine on his back. Drioli the old drunkard, beloved of no one, becomes a semi-priceless work of art. The skin on his back does, at least. I won’t spoil the ending, though it doesn’t take much to guess that it’s a gruesome one.

The Spanish translator opted to call it ‘Tattoo’, perhaps because it seemed to him more dangerous, thuggish and sinister than ‘Skin’, but this is a mistake, because the story isn’t about the tattoo but about the canvas. The metaphor is the epidermis: that is the place where we carry our dead friends with us. The drunken nights we’ve shared remain forever in our pores and hair, which develop wrinkles in accordance with the hardening of collagen. They transform as we ourselves transform. If a restorer were to examine us with x-rays, they would discover a thousand layers of sketches and touch-ups, illegible artists’ signatures that we have forgotten, and even the hazy outlines of unborn children.

Growing old consists of giving an account of oneself, but my monstrous skin tells of the future, not the past. It gradually dies, showing me what I will be; it has no interest in what I have been. It anticipates biological degradation, the return to an embryonic, amorphous, bloody form that closes life’s circle and shows that there never was nor ever will be any soul to sublimate me: only cells, flakes, dust, dried blood. The body at its purest.

Why go on digressing and feeling sorry for myself? We monsters are such a drag, forever whimpering away in our towers and dungeons, egoists to a one, feeling the pain of the world’s disgust – when in fact the world doesn’t give us a second thought. The Beauty and the Beast have something in common, in that both feel they are being watched. The narcissism of the beautiful and the ugly is one and the same.

I want to tell my son about my life line, about the death that hasn’t come but surely will, about my real witches and the red dots on the soles of my feet. I want to create a bestiary of monsters for him, of my fellow beings, individuals devoured by the same psoriasis that leaves me so broken. All of this I will write, so that he may read about it when I’m not there to tell him, or it doesn’t make sense for me to do so, because I’m no longer tucking him in, saying sleep tight, or leaving the door ajar and the kitchen light on.