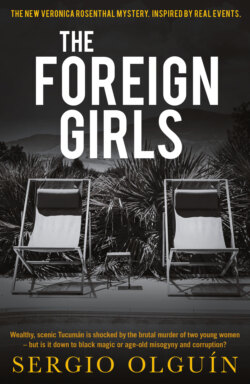

Читать книгу The Foreign Girls - Sergio Olguin - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 New Moon I

ОглавлениеFlying made her sleepy. Any time she had to take a long flight, she slept for a large part of the journey and only woke up to eat or go to the bathroom. People must think she took sleeping pills, but it was just the way she was. She couldn’t even stay awake on a two-hour flight like the one she was on now to Tucumán. Only the shudder of the plane as it touched down at Benjamín Matienzo airport made her open her eyes. Verónica stretched and looked out of the window at the other planes on the ground, the trailers stacked with suitcases and the airport workers moving around.

After collecting her luggage, she went to the car rental office. She had reserved a Volkswagen Gol to take her as far as Jujuy. A small and practical car. In Buenos Aires she made do with borrowing her sister Leticia’s car every now and then, because she didn’t like driving in the city, but the prospect of a journey through Argentina’s north without having to rely on buses and timetables, taking back roads and stopping whenever she liked, was appealing enough to persuade her to hire a car.

The rental company employee asked her name. 24

“Verónica. Verónica Rosenthal.”

Together they walked to the parking lot. The employee made a note in the file of a couple of scratches on the body-work, showed her where the spare wheel was and how to remove it, reminded her that she must return the car with a full tank and finally handed over the keys and relevant documents.

Verónica switched on the GPS she had rented along with the car and entered the address of her cousin Severo’s house in the centre of San Miguel de Tucumán. She lowered the window and felt the breeze on her face, in her tousled hair. A kind of peace swept through her body.

She hadn’t felt like this for a long time. During the last few difficult months there had been only one objective: to get through the day. She had been like a patient in a coma, except that she walked, she talked, she got on with her job. She didn’t want anything, seek out anything, need anything. She tried not even thinking. How long could she have gone on like that?

Verónica’s colleagues at the magazine, her family and friends would have had no hesitation in describing her as a successful journalist. When she had started working in journalism it had been with the dream of exposing corruption, injustice, lies. She had been not quite twenty with everything ahead of her, both in her own life and in the wider world. If someone had told her then that at the age of thirty she would take down a criminal gang that gambled on the lives of poor children, she would have been proud. That was exactly the kind of journalism she wanted to do. And she had done it. She had put a bunch of men behind bars who were responsible for the death and mutilation of boys. She had exposed and eliminated a gambling racket that nobody had investigated before her. No kid would ever again stand on a 25train track waiting for ten thousand tons of metal to come thundering towards him. But she had also paid a price she had never imagined: Lucio, the man she loved, had been killed, a victim of the same mafia.

She had published her article while her grief over Lucio’s death was still raw. The repercussions were such that, in the days following the publication of her piece in Nuestro Tiempo, she had been expected to appear on various television and radio programmes. She had given the requisite answers to her colleagues’ questions, smiled at the end of every interview and thanked them for inviting her on. How could she have told them the truth? How could she put into words the anguish of knowing that one of her informants, Rafael, had so nearly been murdered? What would have happened if one of those condescending colleagues had asked what she had done to save the lives of Rafael and the doorman of the building where she lived? She could have answered: It wasn’t easy. I had to commandeer a work colleague’s car to get there in time. I found four professional assassins about to slay Rafael and Marcelo and had no option but to drive into them. Run over all four of them.

The journalist would have considered this with an expression of utmost compassion. They would have asked how she had felt at the moment she crushed the assassins.

Relief, knowing that two people I loved weren’t going to die at the hands of those brutes.

But nobody would ask those questions, nor did she want them to. She preferred the generous silence her boss and her colleagues had brought to the reporting of her article. The fearful silence of her father and sisters. The complicit silence of her friends. The critical silence of Federico.

She had spent the summer going between the newsroom and home, home and the newsroom. Knowing that her colleagues with children preferred to take their vacations 26in January and February, she had asked for leave in March. She spent much of the summer helping Patricia, her editor, writing twice as many lifestyle pieces as usual, filling pages. The bosses would be happy.

For some time Verónica had been thinking of making a trip to the north of Argentina. She had been to Jujuy with her family as a child but didn’t remember much about it. It was her sister Leticia who had said she ought to go to their cousin Severo’s weekend house. Strictly speaking, Severo Rosenthal was the son of a cousin of their father’s who had moved to Tucumán decades earlier. Severo had studied law at the Universidad Católica Argentina in Buenos Aires, and during those years her parents had treated him like a son: he often went to eat at the Rosenthal home; some nights he even stayed over. Verónica would have been not yet ten at the time.

After he graduated, Severo worked for a time at Aarón Rosenthal’s law firm, but soon afterwards he returned to Tucumán. Supposedly he was going back to the provinces to do what he eventually did: forge a career in the provincial courts. But when Aarón talked about his cousin’s son he often said that he had “got rid of him” because he was “slow on the uptake”. Whatever the truth, Severo was now a commercial judge. He had married, had children. And along with these accomplishments he had acquired a spectacular weekend house that was every now and then at the disposal of the Buenos Aires Rosenthals, perhaps to repay them for the many meals they had shared with Severo in his student days.

When Leticia found out that Verónica was planning a trip to Tucumán, Salta and Jujuy she urged her to spend a few days in that house. She also gave her two other instructions.

The first was “Steer clear of the Witch.” That was how she referred to Severo’s wife, Cristina Hileret Posadas, who was from a traditional northern family. The Rosenthal sisters 27had never liked her, not that they considered Severo a great catch or anything. But to fall into the clutches of someone so bitter, bilious and pessimistic, whose only redeeming feature was having family money, struck them as a terrible fate – even for Severo.

Her second piece of advice was this: “You should definitely visit Yacanto del Valle. The town is really pretty. Plus the Witch has a cousin who lives there, and he’s hot.”

For the first time in many years, Verónica was considering following her older sister’s advice.