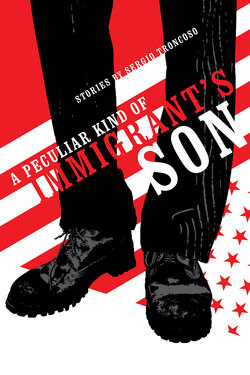

Читать книгу A Peculiar Kind of Immigrant's Son - Sergio Troncoso - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеROSARY ON THE BORDER

I am glaring at a casket: can that be my father, that shrunken, waxlike face? These idiots wouldn’t put just anyone’s body in there, would they? His face is so gaunt, his slight smirk now a permanent smeared smile. Did he lose that much weight? His mouth tight around his lips somehow, as if his skin is already stretching against his skeleton and melding with oblivion. Did they sew his mouth shut? When a body is embalmed, is it hollowed out and left as a meaningless sign for the living? When Ysleta’s Mictlán Funeral Home—next to the Walmart on Americas Avenue—embalms you, well… But it’s him, I think. It must be him. I haven’t been home for a while, the rooms all seem smaller, my father…

Adán sidles up to me. He has lost a lot of weight, had his stomach stapled, but he looks shriveled somehow, not exactly healthy. I ask him, Is that our father? He reassures me. “Yes, of course, that’s our father. He lost a lot of weight the past two months. Hey, can you read this tomorrow, at the mass?”

“Yes, okay.” I know he knows I don’t believe in these rituals anymore, yet he still trusts me. Or pretends to trust me. The dutiful, once-fat Adán, the priest-who-never-became-a-priest. He hands me a sheet inside a wrinkled plastic cover as my eyes trace the contours of my father’s body. Maybe Adán just doesn’t want me to screw anything up.

“It’s easy. Take it. You’ll sit next to me and Pablo tomorrow, and we’ll be reading from the Bible too. I’ll tell you when and everything.”

Adán must’ve seen the nervous look in my eyes: I don’t want to screw anything up either. For years, my older brother has volunteered at Our Lady of Mount Carmel. Me? I often imagined Christ-on-the-Cross rapt, and not from pain. Okay, I’m a non-believer, but I don’t have to be an asshole about it.

In the middle of leaf-peeping season, I flew from Boston to El Paso for the funeral. Our father made it to eighty-two. That’s something, isn’t it? But I haven’t been back since Christmas, when for six days I could only endure a few minutes alone with my father.

Mom’s next to me. She kissed him a few minutes ago, when the family was allowed first dibs. A slow kiss on the forehead. Like she meant it, and she probably did. What’s it like to kiss a dead man? Could pieces of his skin flake off on your lips? Here in Ysleta they did love each other for sixty years. Despite the arguments, our poverty. Despite the last two years of bedsores, and the diabetes killing Dad. Despite the urine-stink engulfing his bedroom and escaping into the hallway like a gas leak. Despite my mother fainting with fatigue, and my father holding her to “her obligations.” Despite Mom, ‘Señora Big,’ too timid to fight back. She’s always been too timid, and my father too lucky to find her in Juárez. As my father’s body collapsed around him, my mother did not break, but Dad almost yanked her into the coffin with him to el otro lado. His mind never abandoned him, but diabetes destroyed his legs, his arms, his eyes, until he couldn’t roll over in bed. What was left was this demanding, bitter voice from the room next to the kitchen. Mom never stopped obeying that voice.

My sister is here with her daughters, three dark angels. Sometimes I like my sister Linda, and sometimes I hate her. I mean, she’s old like me, already in her late fifties. She’s disorganized, wasteful with money, still “taking classes.” That hasn’t changed since her twenties. Is this an unending school fetish? But you know, my father died three days after she returned from Virginia to Ysleta. Dad waited until Linda was next to him, his favorite, before buying front row seats for that big mariachi concert by Pedro Infante in the sky.

Her daughters are really good at praying. Undulating, like those Jews at the Wailing Wall. That’s what I think a rosary service should be, even if I don’t believe in it. At least respecting what Apá achieved in his life, the good in those green eyes despite their meanness. And I do respect it. Abandoning Mexico for the United States, which he kind of hated, to chase his girlfriend who wanted to be an American. Creating a successful life with less than nothing, while these whiny, red-faced Anglo clowns like Lou Dobbs poisoned the air we breathed. My father loved my mother in this desert for decades. If I think about it, he was a damn good father, there at home, even if he yelled at us, even if he once kicked the hell out of my teenage ass. Yesterday at the house, Elena Martinez, my sister’s best friend from high school, whispered to me, “At least you guys had a real father. Ours was always drunk and gone.” In Ysleta, that’s a compliment.

More people coming in, sitting down. The neighborhood. What’s that noise? Underneath the casket: a little metal cube whirring, emitting a fruity scent around us. Capirotada and mangos to mask the formaldehyde? But that body is not him anymore. That’s not the man who worked two jobs, who wouldn’t accept food stamps even if we qualified for them, who worked his sons worse than wetbacks. I always figured that’s how Stalin did it, to take a country from nothing to something, through industrialization and into the Second World, with slave labor and no-excuses pain. That was my father. A crazed Mexican Vulcan, forging the meat of labor into capital. From nothing but dirt, to money in the bank. From a patch of desert a short walk from the mordidas of Narcolandia, to retiring at fifty-three and traveling to Europe with my mother, to Israel, to Egypt. My father was our Stalin-Moses: he led us through the desert into our forced industrialization, the good ol’ American Dream. Maybe there was no other way. And that’s a good Mexican family. I sure did learn how to sweat, how to bleed, how to fight back in Ysleta.

Tin-tan is here, that son of a bitch, Pablo’s jester from the ‘hood. One of the first ones, too. After all his jealousies because he had a shitty family and made stupid choices. So everything I did, my obsessions with Hinton in high school and Faulkner and Márquez in college, my leap to Boston, my making it as a prof from this desert nada, all of it because my father was “educated,” and his wasn’t? Dad went to agronomy school, for god’s sake! Never saw him pick up a book in his life. And Tin-tan always with his fake smile reminding me on San Lorenzo Avenue that he had dug as many outhouses as I did. Who the hell cares! Does that explain why he’s still a substitute teacher? Why is it that people who never left the ‘hood get pissed off when you fail and succeed, and you fail again, and finally succeed, when your success somehow makes them look bad? Humans are a selfish, petty race. Look at that asshole, kneeling in front of Dad’s casket, praying. Pray to climb out of your conceit, Tin-tan, pray for no more excuses before it’s too late. Your horse-face and pissy attitude won’t ever help you, bro.

God, here comes more of ‘em. Cousin Adriana and her husband, Julio, the narco, ex-Mexican military. Her sister Alma, the whole crowd from Chihuahua. Loudmouths. Hugging everybody. It’s not a coffee klatch! Rita, and the ‘rich’ California cousins. I think she’s at least a university administrator near LA, but look at those Kimmy-K-tight dresses and faux cowboy boots, and yelps of joy with Adriana! I mean, there’s a casket behind you. Dad the dead guy is waiting for a little respect. What’s wrong with them? What’s wrong with us? Sorry, Dad, for our family.

“Sonríe!” I hear a micro-second before two clammy hands squeeze my cheeks, and Adriana’s maroon lips and raccoon eyes float in my face like a possessed Jack-in-the-Box. What the hell is wrong with my Mexican cousin? “Por qué tan serio, David? Sonríe, hombre.” Oh, my god, she’s grabbing my face again! I want to punch her. I mean, is she mentally ill? This is a goddamn rosary, my father’s dead, and she’s telling me to lighten up? I step back from her, horrified, and she continues as if nothing’s happened, to my mother next to me, to my sister, to her daughters, holding out her hand and wishing them condolences.

I glare at Adriana as she moves down the line. Her sister Alma is not like that, but Adriana, there’s something seriously wrong with her. She’s so self-absorbed, like her own dead father, my uncle, my father’s brother. El gran macho from Chihuahua always visiting us in Ysleta, and bragging about his rancho, and piling it on in front of his little brother. Making light of anything my father accomplished, the tight fit inside the living room of our adobe house, the interminable hours at Dad’s construction jobs, El Paso and its dust storms, Ysleta and el barrio Barraca, the weed-infested irrigation canal behind our house. And what did my father say when Uncle Dago guffawed about his great rancho in Chihuahua, and how much plata he was hauling in with his government contracts and connections, and what bull he had castrated, all of it as Dago fucked bitch after bitch on both sides of the border? Aunt Esmeralda, preciosa like a matron from old Andalusia, full of pride back in Chihuahua? How exactly did my father ever respond? My father so timid, always deferring to his braggart older carnal. You know, that’s why so many women have been slaughtered in Juárez. That’s exactly why. This goddamn immortal machismo. This human corruption like la leche. This reduction of human relationships to those who can abuse and those who can be abused. You have to fight the fuck back, if you can. It’s not about reason over there: it’s about movidas and the hunger and cowardice of men, all in a sick Machiavellian fiesta. Ajuúa!

And Adriana, her father’s daughter. So into herself, with her bawdy jokes, even when no one laughs. So willing to humiliate others. I mean, what twist of nature is it when the female of the species becomes the macho? I must have been mentally ill when I had a thing for her in high school. Adriana absorbed her father’s personality, and spits on others with her “humor.” Like an actress, at the center of every conversation. Only Julio she respects, her quiet psychopath sidekick so willing to let her be the show. Man, I almost punched her. “Smile! Why aren’t you smiling at your dad’s funeral?” La Donald-Trump-Mexicana. But I would not cause a fuss, not with my father’s body a few feet away. What is wrong with her? Like she’s missing the neural net for respect. And maybe I’m too much my father’s son. Maybe I’m just another grandiloquent smile in this wasteland desert. Another sheepish Mexican. If I had any guts, I would have shoved her face away. What is she doing? Julio and Adriana in front of my father’s casket. But reaching into the casket! Rearranging my father’s hands! A flower? She’s plucked a red carnation from the arrangement on the casket and shoved it into my father’s hands! Who the—? What’s wrong with her? Some nerve! Who messes with the dead body at a rosary? I ought to just yank her hair back. Goddamn Adriana. Her little brown eyes and pale face. It’s a violation of my father. Jesus, I hate her. She’s staring at my father, with her self-satisfied Minnie-Mouse look. My father, even in death, just another toy for her.

What’s she doing now? Oh, my god! There she goes again! Anybody else seeing this? Who’s protecting my father? Adriana’s hands in the casket again, she with a slip of paper in her hand, arranging it. In my father’s suit? What the hell? She steps back. Julio too. What have they done? I know Adriana’s brother, el pinche self-satisfied Santiago, is an evangelical Christian, and has for years tried to convert my Catholic father and mother. I think Adriana and her brother are Testigos de Jehovah, or something like that. They’re the loonies in suits roaming Ysleta my mother sics our German shepherds on. What did Adriana put inside the casket? That paper? That red-carnation kitschy atrocity. It can’t stay there. It won’t.

Decades ago, when I graduated from college—in fact, the only time Mom and Dad ever visited Boston—we were at South Station, the three of us sitting on a long wooden bench. I remember it was smoky—or at least dust hung in the sun’s rays through the air. We were having a fight—or at least I was fighting with them. Commencement had been the day before, and I had accompanied them to Amtrak, because they were on their way to D.C. to make this trip a kind of vacation. Smiling in his smirky way, my father had quizzed me about what I would do now with a college degree in poli sci, when I would start work. He bragged about how he had survived alone in Juárez, after my culo grandfather had slapped twenty dollars into his palm and sent him out the door. I think my father always believed I was kind of soft, too emotional, not his kind of son, not the Mexican macho he adored in Uncle Dago, not the servant he saw in my brother Adán, not the athlete he admired in Pablo.

I was this strange creature who would and would not do what he wanted, who questioned his values to his face, who had created opportunities he only dreamed about, who had finished an American college degree in an American city as strange as Moscow would have been to any of us.

As we sat on that wooden bench and waited for their train, my mother defended my ambiguity, defended my wanting to keep searching for what I truly wanted, which of course, like any smart-ass twenty-one-year-old, I could not articulate very well. This college, this city had opened my eyes beyond Ysleta, beyond El Paso, beyond the border desert, and now just working to pay bills seemed like a prison to me. I knew I would not be able to think, and that’s what I had relished in college for the first time in my life. A certain openness to my life that I did not want to close. His life had been defined by what he had to do; mine would be, I hoped, by what I could do. In his life, he fantasized about becoming a doctor and forever blamed his father for giving him nothing to achieve that goal. In my life, I had taken a rash leap away from home, made my way with little interference from my parents, and would not give up on my nascent dream.

My father criticized my indecisiveness, my wasting time at school without having a plan. It was more than just that he didn’t want to pay the bills. And really, he hadn’t paid the bills. I had worked every summer, work-study every academic year, I had taken shitloads of student loans, and yes Mom and Dad had sent me hundreds of dollars here and there. But I had carried the load to what I think he saw as a wild gambit in Boston, to this strange, faraway New England school without Mexicans. At graduation, my parents had been the foreigners, much darker than everybody else, with awkward accents, intimidated next to my roommates, friends, and their casually suburban parents.

It wasn’t the money. It was another of my weaknesses, that’s what he used against me at South Station. His green eyes glinted like the edges of Damascus steel. A snide little comment that sliced between my ribs like a switchblade, about my girlfriend, Jean, a blue-eyed beauty from Concord, Massachusetts. My lovely and loving Jean who had sought them out with her college Spanish, and laughed heads-together with my mother; Jean who had accompanied me to El Paso for Thanksgiving my senior year; Jean who was more delicate and sophisticated than the richest Anglo girl they had ever come across in El Paso, Texas.

My father at South Station: “Why would Jean want to stay with someone who doesn’t know what he’s doing? Who doesn’t have a job? It’s time to stop living in a fantasy world. It’s time to be a man.”

I hated him for pitting what he imagined Jean was and what he believed I would never be. I hated him for not believing in me, I hated him for not giving me another chance, I hated him for wanting to slam the door shut on what I could be. I told my mother—because I knew it would hurt her—and I told my father too—because he was next to her—I told them I had always felt abandoned and adopted, that they had always favored my brothers and my sister, that I knew I wasn’t loved by them in Ysleta. I was shouting at them, even as hot tears slashed across my cheeks. I didn’t care that a few others turned to stare at us in that waiting-room cavern. I didn’t care about the propriety or impropriety of what others thought of me, unlike my father. It was the moment when I had felt the most alone in my life, more than that first day as a freshman when I had stumbled with my old suitcases into the dingy, one-room cell, carrying two dozen flautas wrapped in foil from Ysleta.

Thoreau, too, had once been in dark exile in Hollis Hall. I was that iconoclast’s Mexican brother.

Only a few minutes to go, and they would have to leave for their train. I wanted to punch my father. My mother in tears said, of course, she loved me. My father held back, embarrassed, watching both of us as if we were insane, he averting his green eyes from mine. Waiting for him to stand up, I stared through him, my chest heaving in spasms. My mother’s hand reached to hold mine, to calm me. I believed—and did not believe—what I had said. I still wanted to punch him.

I had felt so alone for so many years. Part of it was what I had done by leaving home. Part, too, was having never felt at home in Ysleta.

Then my father, inhaling, finally meeting my eyes again, said, “We love you, David, but sometimes we didn’t know what to do with you. You are not like any one of us.”

I think my father said these words because he never wanted to see my mother in pain. I think he said them because he didn’t want to see his grown son angry and out of control at South Station, surrounded by strangers. He may have even meant what he said, too. I don’t know.

We said our goodbyes. I hugged and kissed both of them politely. My head throbbed. I was alone, and I had always been alone, and they had been together and would always be together. It took me years to understand what this meant.

I made many decisions, some awful and others brilliant, but I found ways to keep that openness in my soul that meant more to me than breathing. I told them over the years what I was doing, how I was trying what no one in my family had ever tried to do. When I was failing, I admitted that as well, and they listened politely. I also knew that’s all they could do. One lonely night in Connecticut, I pulled myself from a window’s ledge. No one else next to me. Another day I chose to do something someone like me should have never accomplished, and yet I did, and kept going. I learned to recognize when others, like Jean, were much better than me, because they had faith in my soul. I believed in very little, but I kept going until I would get tired or defeated, and then I would take time to discover another wall to throw myself at. I was, and I am, and I will be, a peculiar kind of immigrant’s son. I got old, and that made everything better, including me.

The next day I arrive first at Mictlán Funeral Home, my McDonald’s one-dollar coffee in hand. The funeral director, who looks like Freddy Fender, arrives after me and opens the door for the “last-respects family visitation,” before the casket is sealed for burial. I know my brothers will soon be here. My sister is bringing my mother for one last look at her beloved. I imagine she will kiss my father one last time. I finish my coffee before stepping inside.

My mother was crying last night, in Ysleta, in front of her bedroom. I could tell in her eyes she was lost, waiting, waiting… for him who would never return. I closed the other bedroom door where my father had died, to prevent the scent of urine from escaping to the kitchen. I looked at my mother as we sat in the kitchen. She trembled as she walked, my eighty-year-old mother, a homemade green apron around her black dress. Her eyes were bloodshot and drifting. She got up to serve Adriana and Julio salad, and she hugged Alma and Rita and asked about their children, the kitchen full of family just as the funeral home had been jam-packed earlier for the rosary. Someone even bragged about how many had attended the service. Old friends. Cousins. Neighbors. Visitors from Chihuahua to Los Angeles. Los compadres y las comadres. Neighborhood hypocrites and hangers-on.

My mother mentioned to somebody about that odd empty space next to the Formica counter, where the case of water bottles was now, that’s where her husband would sit for hours in his wheelchair, with his television tray. She grabbed a tray of food, offered it to someone, or remembered she was about to offer it to someone, her mind suspended between thoughts, neither here nor there. I could tell she didn’t know what to do, to be a host or not to be, to continue, and how to continue.

Over time she would be better.

When there was a lull in the conversation among the eaters at the kitchen table, she said, “Ahora tengo que valer por mi misma.” Now I have to believe in and fight for myself.

What an odd thing to say, I thought. She was so old, she wasn’t a child or young adult anymore. Shouldn’t you be doing that your entire life? Shouldn’t you be doing that when there was still time for you? Both my parents had possessed timid personalities, my father having been thrown out by his father, my mother having endured her often violent mother. Sometimes I imagined them as “old children,” still fighting wars that had ended decades before, frightened children-adults who had discovered each other amid the rubble.

But together they had not been timid parents, together they had accomplished more than most in this poor neighborhood. Together they had found—what?—something stronger than this godforsaken earth?

The funeral home’s chapel is empty. I walk to the casket, and my father is there. Yes, it’s him all right. Thinner, but it’s him. I can’t see his green eyes, but I know it’s him. I’m alone with him for the first time in a long time. Strangely, I don’t have any fear of death. That’s one thing he has given to me. I look around at the empty pews. I am for sure alone with him. Is he self-contained? Maybe that’s not exactly the right word. It’s more like, what he is now is not who he was. That’s over. What’s left is this ceremony for us.

My father did what he wanted to do in his life. He married the love of his life, and he stayed with her despite their troubles and disasters. He was often different, even antagonistic, to who I was and who I would become. There were many times when we didn’t understand each other, when we couldn’t. The times that shaped us were also poles apart. Now, together again, with this strange result: I don’t have any fear of death, now that I see it in front of me, now that I see my father. I do not fear that only this fragile armor of meat surrounds this self. I think Shakespeare was wrong, at least for some of us. Yes, I think, for some the undiscovered country is not death but life.

The little metal cube still hums and emits an orange scent underneath my father’s casket. I take the stupid red carnation out of his hands. They are surprisingly stiff. I put the flower back inside the arrangement on the half-closed casket. I leave the rosary beads wrapped around his fingers because that’s how he and my mother would have wanted him in eternity. I search the nearest pocket in his blue suit, and find Adriana’s slip of paper. It is indeed a goddamn Jehovah prayer. I crumple it into my own suit pocket. I step back. Before I settle into my stance to guard him, a sort of privilege I now think, I hear the double-doors open behind me. I think I hear Adán’s voice, and others, but I don’t turn around for them. I face only my father and who I am.