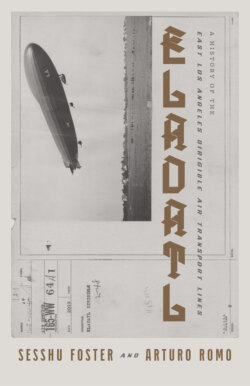

Читать книгу ELADATL - Sesshu Foster - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHEY SAID SOMEONE WILL COME

Sergio pumped the camping stove, a backpacking stove with a cylinder of kerosene that had a pressure pump arm that he had to pump to prime the vaporizer, the nozzle, to emit kerosene vapor could be lit with Strike Anywhere matches. That was how he understood it to work, even though it was always trial and error in the beam of a flashlight, dust motes wafting through its pale light inside the vast dark of the hangar, random punctuations of the interminable night.

One valve had to be open, or both—he always forgot the details of the correct sequence to follow, it always took a long time to start the stove (he was never certain it would start)—

The match got too low, and he flinched and flung it into the darkness, shaking his hand.

He could hear his breathing.

After the (he stopped to listen, but he could only hear his own breathing, couldn’t see anything beyond the beam of the flashlight aimed at the stove perched on the corner of the rusty steel desk)—after the stove was lit he would pour water in the pot for tea.

But first he had to get it lit.

It was always like this getting the stove started. He had never decided finally and absolutely once and for all that he should get a new stove. The trouble was that this one always worked. He’d told Jose and Swirling more than once that he needed a stove if he was going to be sent out on solo reconnaissance missions. They always agreed to anything he asked for, since he was dependable (that in itself somehow seemed a miracle) and took care of everything on his own. Then they’d given him a couple old relics, propane or butane stoves, that were too heavy or were missing parts or had no gas canisters. Swirling just shrugged. “You have to drink tea?” he asked.

Sergio was tired of working with jokers or pissing alcoholics.

Whatever those guys were.

Because he was a recovering alcoholic, and he just wanted to drink a fucking cup of tea.

He distracted himself by griping in his mind about the losers he had to work with in the East Los Angeles Dirigible Air Transport Lines. Swirling only heard what he wanted to hear, Jose didn’t know how to tie his shoes, and then the big boss, Enrique Pico, always away on BIZNESS. After a while, Sergio got the pump to work, the nozzle to gassify, and he lit a flame that rushed from fluttering yellow to focused blue. It emitted a small roar.

The water would only take a couple minutes to boil.

The desiccated leather chair with alkali scum of evaporation on its cracked seat looked like it would collapse if he sat on it, so he pushed it aside. It rolled with a hollow gritty noise that resounded within the office, with its wide, empty window-frames yawning out into the abyss. He’d make do temporarily with a file cabinet he laid on its side (bits of debris skittered internally, fragrance of rat shit).

Sergio relished a moment of decision, selecting a bag from his stash of matcha green tea, Ceylon breakfast tea, Pike Place Market cinnamon tea, African rooibos and Chinese restaurant oolong.

As the tea steeped, enameled cup hot in his hand, Sergio picked up the flashlight and went off looking for a chair, with the expectation that instead he might find treasure. “At the very least I will find a chair.” Part of his mind was focused on the thought that finally, now, with a cup of tea (some corner grazed his thigh, some steel angle—he immediately stopped.)

He pointed his flashlight and his headlamp down and saved himself, saved his own life (One more step and he might have fallen through the hole. Into blackness of space. Something huge and heavy falling from above had apparently torn away the steel railing and bent the walkway down into the blackness, so that one more step and he might’ve slid off into nothingness of space till he landed some second or two later with a hard slap on the concrete and debris several floors below, he saw now, with his heart thudding in his ears.) barely a tremor in his hand as he lifted the cup to his lips.

What had fallen? One of the huge, almost car-sized units formerly attached eight, ten stories or whatever it was above the plant floor? Or something brought down by teen vandals? He’d better keep his wits—or his one wit that he had left—about him. Sergio told himself that he had not had his cup of tea yet, that was his problem. That was why his thinking was muddled. That was why.

Matcha green tea would restore his thinking, he would be thinking right again. His head would be good again. He stepped back from the brink, back from the slippery slope of Death. Switched off the flashlight, then the headlamp, dropping the curtain of sudden pitch black. He sipped from the cup, allowing his sight to recover some glinting details of ambient light from the immensity of the abandoned aircraft plant they’d sent him to reconnoiter. He could hardly be irritated that they had assigned him no partner, no backup (crucial if you fell in utter darkness and broke your legs or your spine, a partner could get you some help before the death agony), since he had assiduously promoted his own reputation for utter independence, total reliability and unassailable, overwhelming competence. Dismissive as he was of others, having established urban reconnaissance skills at a far superior level in his own eyes and then in theirs, sometimes (he listened for any sound, but heard only the creak of his weight shifting on the grating, his own breathing and the sound of his slowing heartbeat, fear remaining localized like a chill in his thighs and stomach) yeah, sometimes it was stupid to go out without a partner. You could die out here. Just one wrong step, some mistake.

He switched his lights back on and checked the stability of the walkway overall, deciding it was only the outer edge that had been compromised. This by stomping on the steel grating and listening to the quality of the reverberations at a couple points. Which sounded all right, basically, so far, but in his report he would advise that work teams should exercise extraordinary caution when traversing the higher levels of the plant. And he’d need to try to think right if he wanted to survive to make that report. Why all the lame thoughts, poor thinking on his part?

Just the way it goes. Try to snap out of it. (sip of green tea) About him swirled an impenetrable darkness, falling out of the universe of night, pouring through the shattered roof eight stories above the cavernous hall. Torn, crumpled railings and bent walkway threatened death in various directions, leading him toward instant emptiness, though he had his headlamp switched on. Little swirly flecks or motes floating across murky currents of dank air reeking of rust, mold, dust heaps of history.

Sergio had no use for the emptiness pouring out of dark night and space. He furiously swept out his “office”—masonite debris, broken glass, former telephone books that were now wavy, porous blocks of cellulose, empty cans of something, strange dirt (from where?), went flying off the gangway into space. Though it was just a glorified glass booth (with some shattered panes, and a large Plexiglass window, discolored and aged with intricate fractal webs of cracks), it had a file cabinet (bottom drawer did not open), massive steel desk with cracking, charred Formica top, miscellaneous chairs (all damaged but quasi-functional), and, importantly, an old beige rotary telephone, which he plugged into a line that could not have been operative for decades. Immediately he began receiving calls.

Sergio took call after call. “East Los Angeles Dirigible Air Transport Lines, how may I direct your call?”

“No, sorry, he’s not here.”

Sergio sniffed, trying not to sneeze. These recycled offices always attacked his allergies with the infinitesimally ground-up particles of blasted lifetimes, stymied Chernobyl/Fukushimas of collapsed economies.

“No, those guys are never around. They might be out back. Can I take a message? They might get back to you.”

Sergio took a number of calls, and after 45 minutes he unplugged the phone. He set it on the corner of the desk at a jaunty angle, indicating its readiness to receive more calls when he plugged it back in. He set the pad (with the “ELADATL Con Safos” logo in one corner) and pencil beside it, topmost notes visible.

Then he zipped up his favorite nifty jumpsuit (with the Amoco patch over his heart that said “Ray”), hefted his tool belt, his water bottle, and his broom, and made his way along the steel mesh gangway that ran the length of the building to the stairs at one end.

They said someone would come, meaning he could count on help, but they always said that. And their volunteers were worthless even when they did show up; he had to spend more time babysitting them, keeping them from killing or maiming themselves in the hazardous environment of the abandoned facilities that were a major part of (and supplier of parts for) his job. Which was, that is, rehabbing and renovating the abandoned plants so they could be used to produce either a movie of a dirigible or the actual aircraft itself (depending on whether you spoke to Swirling or to Jose or to Ericka, or whichever ELADATL faction you might speak with, though you didn’t have to worry about getting into a face-to-face argument, because the factions hardly communicated except by Internet static, flinging little insults and wannabe cutting remarks like sparks spitting off a chain dragging behind a junk truck on a 3 a.m. street). Either the movie about dirigibles that the Fictive faction insisted would be the necessary first step aimed to cure ELADATL’s financial ills, or the clandestine dirigibles proposed by the Real World faction, which they insisted were necessary to restructure the entire transportation grid of California, which would transform the entire collapsing once-dominant U.S. economy (with a blockbuster summer dirigible movie just a spin-off and product-tie-in, its profit earmarked for more worthwhile, maximalist goals). Of course, the movie faction insisted that they themselves were the realists, while the other faction was a bunch of idealists, voluntarists, and adventurists, total lunatics untethered to reality. The rejoinder from the pilots flying actual clandestine dirigibles through the unlicensed air spaces of night was that they were the real realists, and the movie faction was just a bunch of armchair fantasists, artists, and hipsters dedicated to the idea (but not the practice) of actual lighter-than-air flight. When it got really nasty, each side was talking shit about who had money and who didn’t, who lived where, who was from L.A. and who wasn’t. The infighting was often bitter—fulminating over endless persecution by the feds, the police, the Mexican Mafia, you name it—causing drunken brawls and minor bloodshed in forgotten dives across East L.A.

Rank-and-filers like Sergio had to wonder if these natterings of brittle, fatigued leadership were signs of doom, crack-brained utopian delusion (as he had been told, and often, by losers in the street). (“Word in the street—”)

He had to keep his mind on one thing at a time if he wanted to stay alive in the pitch blackness of the abandoned aircraft plant, which stood in partial ruins over a 3-mile-wide underground lake of Chromium-6-tainted water. The ruined plant (abandoned by Lockheed Martin in 1991) tried to maim and kill him via rusted railings that detached when leaned on, stairsteps that fell away into the abyss when you let down your full weight on them, random holes in the flooring where pipes and conduits or elevators or stairwells had been removed, etc. Even if he just stepped into a shallow hole and broke an ankle, like one of his short-term volunteers had done, it could mean days of misery before anyone came looking for him (that was one chirpy volunteer’s first and last ELADATL experience).

They would only have a few week’s use of this plant until it was razed to make way for the many bulldozed acres that were to release Chromium-6-laden soil to the winds for a couple of years until the developers figured out how to put a big-box shopping mall on the site. And when the leadership, minis and maxis both, found out about a plant’s “availability,” they always called in the forward team. Sergio was the forward team.

Given the shortage of members (who usually could be found reading angry spoken-word poetry in Long Beach coffeehouses, or singing sad versions of sones huastecos on the sidewalks of Koreatown, or defecting to the Food Not Bombs collective in Highland Park, or making clever online comments about the latest movies rather than actually putting in hours of labor), particularly on the graveyard shift that was his specialty, this forward team was Sergio alone.

But they said someone would come.

They didn’t say for sure who it was that killed Sergio on a night like this. They denied the rumors that it was an internal ELADATL security squad sent by one faction to take out a suspected member of the other faction, or an FBI Cointelpro-style provocateur playing that role. Most likely, they said, it was a psychopathic loner who read too many Conan the Barbarian comic books while listening to Classic Rock who chopped Sergio to pieces with a machete, who waited till Sergio was busy hammering, welding four hours straight, dragging scavenged steel frames into a circular pattern laid out on the ground floor in advance, concentric constellations of blue LED lights casting a distant pale glow like distant stars made of ice chips, reaching above his head to climb back up the ladder, when out of the dark he heard the faint indication of a footstep—

That was one of his repeating nightmares, which Sergio replayed and discussed in his mind while measuring out great concentric circles in charcoal on dank concrete (lit at crucial intervals by solar-powered lights stolen from the front yards of helpful homeowners across the state of California—ELADATL officially thanks them here for supporting the next new era economy). He didn’t know that his assassination was actually in writing somewhere—it had gone past the whisper campaign and moved through the final planning stages; he thought it was only in his imagination that he was going to be killed doing his clandestine duty for the people of California and the underclasses of the Americas (North and South), but what if his paranoia—that distant ticking or those slight sounds from odd corners of the pitch-black great hall of the generator room, deep inside the cavernous building—was a killer actually making his way stealthily toward him across the vast dark space.

Sergio did his best to remind himself that he was just paranoid, as usual; you had to keep your wits sharp to survive the usual dangers of any postindustrial wasteland. A little voice at the back of his mind suggested that perhaps the minis had tipped off some malevolent Homeland Security death squad that Sergio represented the maxis’ best hopes in their effort to take over the entire ELADATL organization and replace the leadership with radicals who represented a direct attack on the capitalist 1% that ruled America with fascist force backed by NDAA legislation and endless piddly-assed laws against everything and your mother. Municipal ordinances, local laws, institutional regulations, state codes and federal legislation against terrorism and conspiracy and thinking, rules about everything from where and how you could walk the earth and chew gum at the same time, draw breath and how long, not to mention which verbal expression might be allowable when they towed your car from the 30-minute parking zone. God forbid if you showed up at the collective meeting and ever forgot Roberts Rules of Order, and—

What was that sound?

He could swear he heard a dry tick, like the steel blade of a machete accidentally scraping on cement.

Hopefully it was nothing, because he still had the front carapace of the dirigible to weld into place in the five hours left before dawn, if he was going to be ready by the time Swirling had said he was going to arrive with a carload of potential investors for the movie (if they were that kind of investors) or the dirigible fleet (if they were those other, harder-to-find investors). The aluminum conduit, thermostat and drain cocks, brass tubing, blower unit housing, cold air ducts and coolant lines that Sergio welded, bolted, drilled, hacksawed, ground, sanded, engineered, framed, scaffolded, lifted, pulleyed, swung, chained, tied, hammered, sledged, screwed, fused, wired, electrified, cantilevered, extended, raised, oxy-acetylene-torched, arc-welded, stapled, grommeted, tacked, maneuvered, moved, hurled, spun, forced, handled, sorted, joined, expoxy’d, Super Glued, powered up, connected, hot-wired, grounded, ionized, jerry-rigged, and banged together would have to look visually impressive so as to impress the hell out of motion picture producers, on the one hand; and it would need to have an actual chance of getting off the ground, in order to meet the requirements of the outlaw capitalists captivated by strange dreams of lighter-than-air solar-powered or self-charging airships on the other. In short, he had one night in which to make ELADATL happen—or not. Others put in a similar predicament might have been resentful. Sergio certainly was.

But he had work to do. He was doing it!

What was that?

Did a couple of the distant LED lights just flicker, out there beyond the perimeter of darkness?

Anyway, how could he see anything, green spots in his eyes after welding the concentric circles of the hull into place, and the gangways too, laid out and welded along port and starboard. By that time, Sergio was glistening with sweat, his skin blackened by carbon dust and fiberglass insulation dust and ancient dust. His hair bristled through the goggle straps; strands of black hair hung in his face, his forehead smeared where he’d brushed it repeatedly away. He figured he probably needed a haircut.

They said he’d never seen it coming. He was so engrossed in his work, as usual—building an entire dirigible by himself (or the representation of one, according to the movie faction)—that he hadn’t even heard the figure zigzagging through the emptiness of the great hall toward him as he bent over the framing, electrode holder in a thickly gloved fist. Occasionally, he’d jump up, rush over to the portable generator and shut it off.

Sergio would grab the big 25-watt HID rechargeable spotlight and furiously swing the 20,000,000-candlepower beam in great arcs in every direction to verify that he was totally alone. As the vast shadows of building materials, framing and debris leaped wildly back and forth, he felt alone in this strange endeavor—not just in some existential sense but, more importantly, there at the base of the ladder. Darkness shuddered and wobbled in big clouds in all directions above him, but the great hall, with its various foundation struts and structures scattered across the floor resolved into shaky definition under the white spotlight. Then he switched it off, giving his eyes a moment to readjust to the darkness, reaching upward—

That is—he heard the slight—

Too late—

Fuck it, he had to put that bullshit out of his mind and get his work done. This paranoid thinking—occupational hazard of certain jobs on a graveyard shift—was going to cause him to weld a hole in his hand or something stupid like that. Maybe he should take a break and have a cup of tea. The trouble was, to get back upstairs to his “office,” fire up the pain-in-the-ass camp stove and boil water would take half an hour, which he didn’t have. Probably—

BAM!

Lights out!

That was the way he expected to go out. Some psycho loser was going to take him out when he wasn’t looking, or he was gonna fuck up and touch a hot wire and bite his tongue through, shattering his teeth, 150,000 kilowatts torching every hair off his blistering skin. Meanwhile, he positioned himself above the juncture to begin his next bead.

He should have taken a tea break. He should have fired up the stove back in his office and made a cup of organic South African rooibos.

Or, something he’d done more than once, he should’ve poured a cup of cold water and thrown a tea bag of anything in it and come back later to drink it. Even that would have been better than nothing.

As it was, he knelt down to lift a heavy stanchion armature onto his shoulder and drove an eight-inch-long piece of steel wire (that he had somehow miraculously avoided all night) through his leg, through the meat of his left calf and the pants leg of his favorite grease-stained jumpsuit. He gasped, a tremor of agony shaking his entire body, and leaned slightly to his left, tossing the heavy stanchion far enough that it would not rebound onto his own injured limb. He stifled the screech that rose in his throat as he lifted his leg off the wire, the length of it sliding out with a friction audible in Sergio’s hissing exhalation. He growled a long string of banal cusswords and sat on the one bare patch of dusty cement floor he could vaguely make out, his attention drawn to the nastiness flaring up his leg. He wrapped his hands around the wound, which he could feel leaking warmly through the fabric, sighing. “Ow, fuck,” he added.

Then he limped toward the stairs at the far corner of the vast ruin. He’d have to pour hydrogen peroxide into both sides of this wound so he didn’t wind up with tetanus. He’d get the cup of tea that had been in the back of his mind for some time.

On the final night, did he even see the figure that separated itself from the shadows?

Although he always kept a pair of bolt cutters handy in his truck at all times, Swirling was glad he did not have to interrupt his spiel about the dead economy, California’s once-great, eighth-largest (or fifth-largest according to some estimates) world economy and its ever increasing population, 38 million at last count, the dead economy freeing up space both actual and intellectual for airships of new thinking, forward bound, filled with the helium of dreams.

Sergio had, as usual, cut through the chain and hung the lock so that it appeared locked; so Swirling could swing out of the cab, with the Germans safely tucked inside as the dawn streaked brightly across the puddled expanses of empty pavement, pull some keys from his pocket to “unlock” the lock, open the sagging chainlink gate, and drive his quiet, bemused bunch through to the still vaguely impressive facilities.

It was clearly all fallen into disrepair but the Germans had been told all that. They had been told all sorts of things, parts of it certainly true.

Like the edgiest of venture capitalists, these guys checked their cell phones as often as teenagers. With their open-collared polo shirts and paunches and eco-shoes and salt-and-pepper close-cropped bullet heads, they were not really interested in the grimmest and grimiest of dull details. They expected that to be taken care of in advance. Maybe just one or two morsels to titillate like an appetizer. They wanted the secret glory of the supposed outside risk (that was primarily yours to bear), but mainly they expected insured return (of some kind!) on their money.

That was all fine, Swirling reflected, as he drove across the railroad tracks that cut through the plant, through another gate that Sergio had (as instructed) opened in advance, even though it was worrisome that Sergio had stopped answering his calls sometime after 4 a.m.

He hoped that Sergio had not injured himself or been killed.

That would certainly put a damper on the meetings with this group. ELADATL needed this capital to get to the next phase. Sergio had never failed him before, that’s why Swirling was putting him in charge of all the forward teams (once they organized some forward teams).

Meanwhile, Swirling covered his worry about not hearing from Sergio for hours during this most critical period by raising the decibel levels—roaring through the expanse of the former plant with its mounds of clumpy debris and its empty rectangles of razed foundations shining damply in the dawn light, speeding through the grounds at fifty miles an hour like a low-flying twin-engine P-38 “Lightning.”

Swirling tossed out all kinds of facts and random commentary while he drove, drawing his charges’ attention to this or that and away from his own jittery nerves. When he arrived at the runway—which had been in use as a parking lot but was still recognizably a runway—with the B-1 building adjacent, the huge hangar doors were not open. In the mean light of dawn, they looked permanently closed, nonfunctional, battered and corroded.

“Gentlemen! Time to view our newest prototype!” Swirling said.

He leaped out, swaggered to the center of the nearest hangar door and banged loudly, repeatedly.

“What the hell,” he muttered, banged again, his fist hitting the door that reverberated thunderously inside the cavernous building.

“If he’s working, sometimes he can’t hear,” Swirling explained, glancing at the Europeans from the corner of his eyes. They commenced looking about in the morning breeze and grinned at him, unwavering steady pinpoints of gravity in their eyes.

Swirling was banging again, desperately, when the huge sheet-metal door gently lifted, softly rising into the air.

It went up about twenty feet and stopped, revealing the great hall with its sad, strange stacks and piles of sheet metal, piping and debris scattered about the huge frame of an obvious dirigible, five or more (top obscured in dimness) stories high and hundreds of feet long, what you could see of it, as rays of morning light penetrated the dimness of the interior.

As usual, Sergio had ultracapacitors hooked up to oscilloscopes and generators to produce random electrical thrumming and sizzling far down the tail end of the ship, and he’d left his welding apparatus shooting sparks and had to run over and switch it off, all for effect. This ship produced its own sound track.

The German investment group rushed forward, as if hypnotized by their own expectations. One of the investors with a cigarillo in his mouth (one of their slim brown cigarillos) caught Swirling’s glance, removed the cig and pinched it away in his pocket, grinning and shaking his head.

Swirling took to nodding, as if everything was on schedule.

Sergio made it on schedule.

Sergio dropped the nylon line of the manual pulley he’d had to rig to get the huge door to slide on its broken old tracks; he limped over on his damaged leg to shake hands with the investors. Swirling was explaining some ideology about dirigibles, some shit about self-charging titanium frames and solar power to these guys who had to remove their sunglasses to see into the dimness.

Sergio was tired. He stood behind Swirling till Swirling finally noticed him and introduced him to the members of the investment group, “This is Sergio, head of our Forward Teams division.” Swirling gave the bloody rag wrapped around Sergio’s calf a glance and said, “How’re you, boss?”

Sergio frowned, tipping his head toward the hangar door. The two walked out toward the shining expanse of morning. The Germans talked happily.

“You all right?” Swirling asked again.

“Look, I got blood all over my favorite jumpsuit. Get me out of here,” Sergio said, “I want to change my clothes and have a cup of tea. I don’t want to be late. Unlike you, I got a day job.”

“Absolutely! Let me give our friends the story behind this ship first, then we’re on our way! What a beautiful morning, eh?”