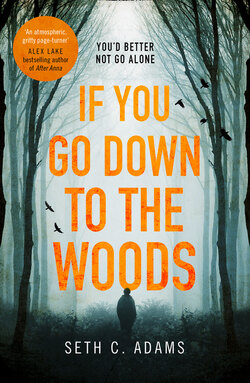

Читать книгу If You Go Down to the Woods - Seth C. Adams - Страница 8

2.

ОглавлениеMy family moved to Payne, Arizona when I was thirteen. My dad, John Hayworth, got a job as the manager of a Barnes & Noble bookstore, and we moved there from Southern California. Mom, a college-educated woman, decided that being a mother was far more important than searching for meaning in the writing of centuries-dead English novelists, and wholeheartedly supported the move. For those prematurely crying sexism, this was a two-way street kind of respect: Dad supported her, offered to be the stay-at-home parent as she climbed the ranks of prestige in academia. But I think Mom saw more value in passing on her passion for the written word to her children, reading us stories snuggled in our beds or on the sofa, than lecturing youth enrolled in electives, packed like sardines in large lecture halls.

My sister and I had to leave our friends, and though I was sad about some of the people I left behind, I also saw it as something of an adventure. Sarah, on the other hand, sixteen going on retarded, acted like she was saying goodbye to her whole life and every shot at happiness. She had some greasy-haired boyfriend that she was leaving behind, some young stud who thought wearing a leather jacket and slicking his hair back with a few pounds of hair gel made him some sort of James Dean. I thought it made him look like he’d melted butter and greased his head with it.

I told him so once.

He flipped me off.

I laughed at him and gave the old jerk-me-off sign language.

Sarah didn’t talk to me for a week after that. That was fine by me. Likewise, I tolerated her like a bothersome rash: it was there, it caused discomfort, but there wasn’t much you could do except live through it.

Looking back, I realize she wasn’t all that bad. I might even go so far as to say she was a good older sister in some ways. But try telling that to a thirteen-year-old boy, just learning the mysteries of girls and the smaller head in his pants, living in a small house with an older sister who liked barging into his room at any hour to bestow upon him the gifts of noogies, wedgies, and wet willies.

Last, but most definitely not least, I can’t forget my dog, Bandit, a German shepherd mix, with some of that mix maybe being wolf. White and gray and silent like some sort of ghost dog from an Indian legend, Bandit was large and stoic and loyal, obedient but obstinate in his own way, and never left my side if I allowed it. He slept in my bed, his loose hairs finding their way up my nose and in my mouth, and my sinuses suffered for it for years. Dad invariably scolded me about keeping that dog in my bed, but there’s something about dogs and boys, how they’re meant to be, and the years that dog spent with me—warm friend, heartbeats lulling each other to sleep on cold nights—and I don’t regret a day.

I remember the long drive through the desert highways to our new home. Hills that seemed to roll to forever in every direction. Sparse trees like stubble on the earth. Mom and Dad took turns driving so the other could rest. Sarah dozed across the seat from me in the back or stared pathetically out the window, a hand under her chin in melodramatic melancholy. Bandit sat or stood on the seat between us, going from window to window, paws on my lap to try to get a good sniff of what was passing us by, and I’d let him, until a stray paw stepped on my nuts, then I’d push him away. I stared out the car windows as well, watched the fiery skies of morning give way to the bruise-blue of afternoon, and remember thinking that though things were changing it might not be all that bad.

I was a simple kid to please. All I needed for contentment and happiness were a good book, some comics, and horror movies, and with Dad a manager at a Barnes & Noble I’d have those things in spades. A whole summer of lazy afternoons, curled in my bed in my room or on a chair on the porch or sprawled on the grass of the lawn, seemed like the superfluous joys of heaven.

The new house didn’t let me down in that regard. I’d seen pictures of it my parents had taken on a trip they’d made earlier in the year to see the property, but the still images didn’t do the majesty of the place justice.

As Dad turned the station wagon off the highway and onto a country residential sprawl of a road, I found myself leaning forward in anticipation. When we turned the last bend, and I recognized the house from the pictures, I alternately gripped the seat and wiped my palms on my jeans.

It sat on two acres of well-manicured land, carpeted by grass the green of emerald dreams. The whole place was fenced by chain-link, which to some might have made it seem vaguely white-trashy in nature, but to my boy’s mind made it seem a secluded fort of a kind. The porch had an overhanging awning and was enclosed by a screen mesh that let you see out but made it hard for others to see in, so all they saw were dark shadows and silhouettes. There was a pool in the back, dry and mossy in places, the cement lining cracked in others, that Dad promised to have repaired and filled soon.

Apple trees dotted the yard, and in the summer the branches were in full bloom and heavy with their juicy burden. The lawn was speckled with the fallen fruit, and as soon as the car braked to a stop with a little cloud of dust, I leapt out, dashed across the grass, scooped up an apple and let it fly. Perhaps thinking I’d filched one of his tennis balls from the trunk without him seeing, Bandit darted out of the car behind me, and charged after the green sphere. Finding it among the litter of others, he spun around in a frenzy, confused and smiling and uncertain by the mass of apples. To his dog’s brain, they must have seemed the sweet, multitudinous edible balls of some canine paradise.

“Come on, Joey,” Dad called after us, stepping out from behind the wheel and stretching. “There’ll be time for that later. We got work to do.”

The moving trucks arrived well before us, and the sweat-drenched men had our boxes ready, piled high in totem-like stacks along the porch. Motioning for Bandit to follow, we bounded up the porch steps together. I found the growing stack of boxes with my name written on them in large Sharpie marker letters and began taking them to my new room.

The work went on for hours, and Dad had a cooler set out on the porch, along with plastic chairs, and we all took breaks when we felt like it. Pop open a soda, cram one of Mom’s sandwiches in my mouth, and for me it was relaxing. Work, yes, but also fun in a way as I looked out across the desert town in the distance. At times my gaze would drift over to the faraway woods bordering the township, and that dense, mysterious greenery seemed to call to me and Bandit.

Slowly, afternoon crawled into the first evening, purple-black over our new home. My bed set up, having unloaded several boxes of books with many more to go, I sat in bed, the window beside it open. The cool desert breeze drifted in and stirred things with a whisper. A volume of Ray Bradbury stories was open in my lap, propped up by a pillow. Bandit was at my feet, large and furry and kicking his feet occasionally with rabbit filled doggie dreams.

The act of reading usually soothing, I had trouble keeping my mind on the pages before me. My gaze kept drifting to the walls and contours of the room. Realizing I’d spent the last fifteen minutes or so on the same page, I finally gave up and set the book aside.

The room was painted an earthy brown and seemed spacious and snug at the same time. I had my own TV, a gift from last Christmas, and I knew exactly where I wanted it to go. Mom promised she’d call the cable company “tomorrow,” and I dreamt of late-night horror marathons. I had boxes of books and comic books yet to be unpacked, and imagined the bookshelves that would line the walls like sentinel soldiers.

There were the other magazines that I had also, buried among my books and filed secretly in between the comics. Magazines of a certain nature all boys must look through at some point, cracking the covers open ever so slightly, ever so slowly, as if lifting the lid to a treasure chest. Treasures they were, too, and I thought of being able to look at these at my leisure in the privacy of my new room.

Then the door to my room swung open and there she was, that rash that wouldn’t go away, a look of demented sisterly pleasure on her face.

“You know what I’m here for,” she said.

And I said: “Yeah, but I’m all out of Ugly-Be-Gone.”

When she charged across the room, I scooped up the book to try and defend myself, and the Queen of Noogies sent me to sleep with bruises and one bastard of a headache.

And the tired realization that some things would never change.