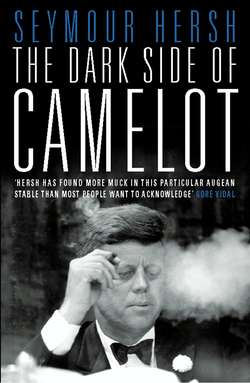

Читать книгу The Dark Side of Camelot - Seymour Hersh - Страница 11

7 NOMINATION FOR SALE

ОглавлениеJohn F. Kennedy’s rise is a story that has been told and retold in hundreds of biographies and histories. The senator, always suntanned, with his photogenic wife and daughter, was the subject of articles for national magazines month after month in the late 1950s. When he wasn’t being interviewed, the senator, who relied on speechwriters on his staff and those in the pay of his father, published scores of newspaper and magazine articles as well as the bestselling Profiles in Courage, which won the 1957 Pulitzer Prize for biography.

Kennedy’s political standing was given an enormous boost at the 1956 Democratic National Convention, when he narrowly lost a dramatic floor fight against Senator Estes Kefauver for the nomination as Adlai Stevenson’s vice presidential running mate in the party’s doomed campaign against Dwight D. Eisenhower. Kennedy’s grace and seeming good humor in defeat, and his boyish good looks—viewed by millions of television watchers—overrode his lackluster record in the Senate and made him an early favorite for the party’s nomination in 1960. Kennedy ran hard over the next four years, spending most weekends making speeches and paying political dues at fund-raising dinners across America.

He made his mark not in the Senate, where his legislative output remained undistinguished, but among the voters, who responded to Kennedy as they would to a famous athlete or popular movie star. From the start the campaign was orchestrated by Joe Kennedy, who as a one-time Hollywood mogul understood that his son should run for president as a star and not as just another politician. In an exceptionally candid interview in late 1959 at Hyannis Port with the journalist Ed Plaut, then writing a preelection biography of Jack, the elder Kennedy said that his son had become “the greatest attraction in the country today. I’ll tell you how to sell more copies of your book,” Kennedy told Plaut. “Put his picture on the cover.” Plaut made a transcript of his interview available for this book.

“Why is it,” Kennedy asked, “that when his picture is on the cover of Life or Redbook that they sell a record number of copies? You advertise the fact that he will be at a dinner and you will break all records for attendance. He will draw more people to a fund-raising dinner than Cary Grant or Jimmy Stewart and anyone else you can name. Why is that? He has the greatest universal appeal. I can’t explain that. There is no answer to Jack’s appeal. He is the biggest attraction in the country today. That is why the Democratic Party is going to nominate him. The party leaders realize that to win they have to nominate him.

“The nomination is a cinch,” Joe Kennedy told the reporter. “I’m not a bit worried about the nomination.”

By the summer of 1960, with brother Bobby serving as campaign manager and father Joe as a one-man political brain trust—as well as secret paymaster—Jack Kennedy arrived at the Democratic convention in Los Angeles as an unstoppable front-runner who apparently had earned the right to be the presidential candidate by running in, and winning, Democratic primary elections across America. He had conducted a brilliant campaign that would set the standard for future generations of ambitious politicians, especially in its relentless tracking and cataloguing of delegate votes. One of Kennedy’s loyal aides, Ted Sorensen, would describe admiringly in Kennedy, his 1965 memoir, how Kennedy went over the heads of the backroom politicians and took his campaign to the people:

He had during 1960 alone traveled some 65,000 air miles in more than two dozen states—many of them in the midst of crucial primary fights, most of them with his wife—and he made some 350 speeches on every conceivable subject. He had voted, introduced bills or spoken on every current issue, without retractions or apologies. He had talked in person to state conventions, party leaders, delegates and tens of thousands of voters. He had used every spare moment on the telephone. He had made no promises he could not keep and promised no jobs to anyone.

What no outsider could imagine—and what Sorensen did not write about—was the obstacles overcome and the carefully hidden deals engineered as Kennedy achieved one political victory after another en route to Los Angeles.

Kennedy’s most important primary victory came on May 10 in West Virginia. In his campaigning in the state, Kennedy directly confronted the religious issue, telling audiences, for example, that no one cared that he was a Catholic when he was asked to fight in World War II. He defeated Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota by more than 84,000 votes. In his memoir, Sorensen quoted another of Kennedy’s unsuccessful rivals for the nomination, Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri, as saying after the convention: “He had just a little more courage, … stamina, wisdom and character than any of the rest of us.”

Sorensen’s account, as with so much of the Kennedy history as told by Kennedy insiders, has many elements of truth but is far from the whole story. The Kennedys did not depend solely on hard work and stamina to win the primary elections en route to the Democratic nomination. They spent as never before in American political history. In West Virginia, the Kennedys spent at least $2 million (nearly $11 million in today’s dollars), and possibly twice that amount—much of it in direct payoffs to state and local officials.

A far more complete account of the campaign emerges in the unpublished memoir of one of Kennedy’s most trusted, and little-known, advisers during the 1960 campaign, Hyman B. Raskin, a Chicago lawyer who had helped manage Adlai Stevenson’s presidential campaigns in 1952 and 1956. Raskin had been recruited in late 1957 by Joe Kennedy, and secretly paid, to help plan and organize his son’s drive for the presidency. Raskin, who after the 1960 election retired to his law practice, died in comfortable obscurity in 1995 at the age of eighty-six in Rancho Mirage, California. His widow, Frances, later provided for this book a copy of his memoir, entitled A Laborer in the Vineyards, which contains a rare firsthand account of Joe Kennedy’s direct, and powerful, intervention in national politics on behalf of his son—interventions that were always hidden from the press. In Raskin’s account, the combination of unlimited campaign funding, Joe Kennedy’s high-level political connections, and Jack Kennedy’s strong showing in the Democratic primaries—especially his West Virginia victory—enabled the Kennedys to fly to Los Angeles knowing they had enough ironclad delegate commitments to win on the first ballot.

At the convention site, Raskin was entrusted with the all-important task of running communications. The Kennedys, in one of their political innovations, had leased a trailer and filled it with state-of-the-art communications gear that enabled the campaign’s backroom operators to reach the leaders of state delegations instantly. In his memoir, Raskin depicted the convention as anticlimactic for the campaign insiders: “We were confident that the [delegate count] numbers which the state reports produced would closely approximate those we had before the initial [convention] meeting was held.… It appeared impossible for Kennedy to lose the nomination. The votes merely needed to be officially tabulated; therefore, in my opinion, if he failed, it would be the result of some uncontrollable event.”

Texas senator Lyndon B. Johnson’s last-minute declaration just days before the convention that he would, after all, be a candidate for the presidency—an announcement that created a flurry of press reports—was too little, too late, in Raskin’s view. “The front-runner was unbeatable,” he wrote. “For unknown reasons, some members of the press refused to concede the nomination of Kennedy, ignoring the arithmetic reported by their associates.… Johnson and his managers must have had access to the same information. Much of it was published and verifiable through Johnson connections in almost every state. Why then, I asked myself, did the anti-Kennedy forces continue their futile struggle?” Johnson stayed in the race until the presidential balloting and suffered an overwhelming defeat by Kennedy on the convention floor.

The fact that Kennedy had locked up the nomination weeks in advance of the convention was one of the campaign’s secrets. There were other secrets far more damaging, any one of which, if exposed, could cost the handsome young candidate his otherwise assured presidential nomination.

The most dangerous problem confronting the Kennedys before the convention was the hardest to fix, for it was posed by a group of reporters from the Wall Street Journal who were raising questions about the huge sums of cash that had been spent by the Kennedys to assure victory in the West Virginia primary. Their story, triggered by the instincts of an on-the-scene journalist, never made it into print.

Alan L. Otten, the Journal correspondent who covered the campaign, had been stunned by the strong Kennedy showing. He had spent weeks walking through the cities and towns of the coal counties and concluded, as he wrote for the Journal, that Humphrey would capitalize on the pronounced anti-Catholicism in West Virginia and win the Democratic primary handily. “Every miner I talked to was going to vote for Humphrey,” Otten recalled in a 1994 interview for this book. The reporter, who later became chief of the Journal’s news bureau in Washington, was suspicious when the votes were counted and urged his newspaper to undertake an extensive investigation into Kennedy vote buying. “We were fairly convinced that huge sums of money traded hands,” Otten told me.

Buying votes was nothing new in West Virginia, where political control was tightly held by sheriffs or political committeemen in each of the state’s fifty-five counties. Their control was abetted by the enormous number of candidates who competed for local office in the Democratic primary, resulting in huge paper ballots that made voting a potentially interminable process. In his Pulitzer Prize-winning account of the 1960 campaign, The Making of the President, 1960, the journalist Theodore H. White noted that the primary ballots for Kanawha County, largest in the state, filled three full pages when published the day before in the Charleston Gazette. Sheriffs and other political leaders in each county made the process less bewildering for voters by putting together lists, or slates, of approved party candidates for each office. Some candidates for statewide offices or for important local posts, such as sheriff or assessor, invariably ended up on two, three, or more slates passed out on election day by campaign workers. The unwieldy procedure continues today.

The sheriffs and party leaders were also responsible for hiring precinct workers and poll watchers for election day. Political tradition in the state called for the statewide candidates to pay some or all of the county’s election expenses in return for being placed at the top of a political leader’s slate. Paying a few dollars per vote on election day was widespread in some areas, as was the payment for “Lever Brothers” (named after the popular detergent maker)—election officers in various precincts who were instructed to actually walk into the ballot booth with voters and cast their ballots for them.

The Journal’s investigative team, which included Roscoe C. Born, of the Washington bureau, spent the next five weeks in May and June in West Virginia and learned that the Kennedys had turned what had historically been random election fraud into a statewide pattern of corruption, and had apparently stolen the election from Hubert Humphrey. The reporters concluded that huge sums of Kennedy money had been funneled into the state, much of it from Chicago, where R. Sargent Shriver, a Chicagoan who had married Jack’s sister Eunice in 1953, represented the family’s business interests. The reporters were told that much of the money had been delivered by a longtime Shriver friend named James B. McCahey, Jr., who was president of a Chicago coal company that held contracts for delivering coal to the city’s public school system. As a coal buyer earlier in his career, McCahey had spent time traveling through West Virginia, whose mines routinely produced more than 100 million tons of coal a year. Roscoe Born and a colleague traveled to Chicago to interview McCahey “and he snowed us completely,” Born recalled in a series of interviews for this book. Nonetheless, the reporter said, “there was no doubt in my mind that [Kennedy] money was dispensed to local machines where they controlled the votes.”

Born, convinced that he and his colleagues had collected enough information to write a devastating exposé, moved with his typewriter into a hotel near the Journal’s office in downtown Washington. He was facing a stringent deadline—the Democratic convention was only a few weeks away—and also a great deal of unease among the newspaper’s senior editors.

As with many investigative newspaper stories, there was no smoking gun: none of the newspaper’s sources reported seeing a representative of the Kennedy campaign give money to a West Virginian. “We knew they were meeting,” Otten recalled in our interview, “but we had nothing showing the actual handing over of money.” The Journal’s top editors asked for affidavits from some of the sources who were to be quoted in the exposé; when the journalists could not obtain them, the editors ruled that the article could not be published. “The story could have been written, but we’d have to imply, rather than nail down, some elements,” Born said. “I really wanted to do it, but I can see that the editors would be nervous about doing it practically on the eve of the convention.” Other Journal reporters were told that Born and his colleagues had “gotten the goods,” as one put it, on the Kennedy spending in West Virginia. The columnist Robert D. Novak, then a political reporter on the Journal, recalled in an interview for this book hearing that the newspaper’s top management had concluded that the West Virginia money story could affect the proceedings in Los Angeles, and it was not “the place of the Wall Street Journal to determine the Democratic nominee for president.”

The Journal’s reporting team was far closer to the truth than its editors could imagine. Jack Kennedy had wanted a clean sweep in the April 5 Democratic primary in Wisconsin, aiming to defeat Hubert Humphrey in all ten of the state’s congressional districts, and he campaigned long hours to get one. He was bitterly disappointed when he won only six districts—and, most important, when his showing failed to discourage the equally hardworking Humphrey, who decided to continue his presidential campaigning in West Virginia. It was understood by professional politicians that Humphrey, too, would be putting in as much money as he could to meet the inevitable bribery demands of the county sheriffs. The Kennedy team also feared that other Democratic opponents for the nomination, Lyndon Johnson and Adlai Stevenson among them, would urge their backers to shove money into the state on Humphrey’s behalf in an effort to stop Kennedy and deadlock the convention.*

West Virginia thus became the ultimate battleground for the Democratic nomination, and the Kennedys threw every family member and prominent friend they had, and many dollars, at defeating Humphrey. At stake was not only Jack’s presidency, but Joe Kennedy’s dream of a family dynasty: Bobby was to be his brother’s successor.

In interviews for this book, many West Virginia county and state officials revealed that the Kennedy family spent upward of $2 million in bribes and other payoffs before the May 10, 1960, primary, with some sheriffs in key counties collecting more than $50,000 apiece in cash in return for placing Kennedy’s name at the top of their election slate. Much of the money was distributed personally by Bobby and Teddy Kennedy. The Kennedy campaign would publicly claim after the convention that only $100,000 had been spent in West Virginia (out of a total of $912,500 in expenses for the entire campaign). But what went on in West Virginia was no secret to those on the inside. In his 1978 memoir, In Search of History, Theodore White wrote what he had not written in his book on the 1960 campaign—that both Humphrey and Kennedy were buying votes in West Virginia. White also acknowledged in the memoir that his strong affection for Kennedy had turned him, and many of his colleagues, from objective journalists to members of a loyal claque. White stayed in the claque to the end, claiming in his memoir, without any apparent evidence, that “Kennedy’s vote-buyers were evenly matched with Humphrey’s.”

In later years, even the most loyal of the loyalists acknowledged what happened in the West Virginia primary. In one of her interviews in 1994, Evelyn Lincoln said, “I know they bought the election.” And Jerry Bruno, who served as one of Kennedy’s most dependable advance men in the 1960 campaign, similarly said in an interview: “Every time I’d walk into a town [in West Virginia], they thought I was a bagman. They used to move polling places if you didn’t give them the money. We didn’t do it better, but we got the people who at least were half-honest. The Hubert people—they’d take the money and then come to see us.”

The most compelling evidence was supplied by James McCahey, the Chicago coal buyer, who refused to cooperate with the Wall Street Journal in 1960. In a 1996 interview for this book, he revealed that the political payoffs in West Virginia had begun in October 1959, when young Teddy Kennedy traveled across the state distributing cash to the Democratic committeeman in each county. McCahey was told later that the payoffs amounted to $5,000 per committeeman, a total expenditure of roughly $275,000. McCahey, who left the coal business in Chicago for the railroad business (he retired in 1985 as a senior vice president of the Chessie System Railroads, in Cleveland), added that the Wall Street Journal’s suspicions of him were wrong: his assignment in West Virginia had not been to make payoffs but to organize the teachers in each county “and help them get out the word about Kennedy.” Through this assignment he was able to learn a great deal about what was going on in the state.

McCahey, a major fund-raiser in 1960 for Mayor Richard Daley of Chicago, was also a strong Kennedy supporter and had been assigned to direct the Kennedy campaign in the southern districts of Wisconsin. After the disappointing results there, McCahey told me, Sargent Shriver telephoned and invited him to an important insiders strategy meeting in Huntington, West Virginia, that had been put together by Jack and Bobby Kennedy, and included Jack’s brother-in-law Stephen Smith, the campaign’s finance director. New polling was showing a precipitous drop in support for Kennedy among West Virginians; the subject of the meeting was how to get the campaign back on track. It was then, McCahey said, that he learned about Teddy Kennedy’s efforts the previous fall to pay for support from the county committeemen.

“It didn’t work at all,” McCahey told me. “You don’t go into a primary [in West Virginia] and spread money around to committeemen. The local committeeman will take your money and do nothing. The sheriff is the important guy” in each county. “You give it to the sheriff. That’s the name you see on the political banners when you go into a town.” McCahey further recalled being told at the meeting that Joe Kennedy believed that the buying of sheriffs “was the way to do it.”

The sheriffs, it was understood, had enormous discretion in the handling of the cash. Some would generously apportion the cash to their supporters; others would pocket most of the money.

McCahey recalled that his essential contribution was to tell the Kennedys “to forget what you’ve done and start again. I laid out a plan”—to organize teachers and other grassroots workers—“and they said go.” He also worked closely with Shriver in visiting the major coal-producing companies in the state, all of which he knew well from his days as a buyer. “I’d drop into the local coal places and ask the fellows, ‘What’s going on?’” McCahey acknowledged passing out some cash to local political leaders while at work in West Virginia, paying as much as $2,000 for storefront rentals and for hiring cars to bring voters to the polls on primary day. He knew that far larger sums of money were paid to the sheriffs in the last weeks of the campaign. “If they did spend two million dollars,” McCahey told me, with a laugh, in response to a question, “they figured, ‘Hell, let McCahey go [with his plan to organize teachers and the like].’ They had lots of angles.”

There is evidence that Robert Kennedy was, as Teddy had been earlier, a paymaster in the hectic weeks before the May 10 primary. Victor Gabriel, of Clarksburg, a supervisor for the West Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission who ran the Kennedy campaign that spring in Harrison County, recalled in an interview for this book a meeting before the election with Bobby and the ever-loyal Charles Spalding. Gabriel told the two men that he needed only $5,000 in election-day expenses to win the county for them. The exceedingly low estimate, Gabriel told me, caused Spalding to exclaim, “You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Gabriel, eighty-two years old when interviewed in 1996, refused to take any more cash and delivered his county, as promised, on election night. Gabriel joined other Kennedy workers at a gala victory celebration at the Kanawha Hotel in Charleston. At some point during the party, he said, a grateful Bobby Kennedy ushered him into the privacy of a bathroom and pulled out a little black book. “You could have gotten this,” Kennedy told him, as he pointed to a page in the book, “to get people on the bandwagon.” Kennedy’s notebook showed that as much as $40,000 had been given to Sid Christie, an attorney who was the top Democrat of McDowell County, in the heart of the state’s coal belt in the south. The Kennedy notebook made it clear, Gabriel told me, that the campaign had “spent a bundle” to get the all-important support of all the sheriffs and political leaders in the south.

Gabriel told me that he had no second thoughts about the relatively small amount of Kennedy money he had requested. “I told [Bobby] what I needed and didn’t take a damn dime more,” Gabriel said. “All I had to do was tell him fifteen thousand or twenty thousand, instead of five thousand, and I’d have got it. But I don’t operate that way. If you’re going to be for a man, be for him.” The sheriffs who took more than $5,000, Gabriel told me, were simply pocketing the money.

Two former state officials acknowledged during 1995 interviews for this book that they also knew of large-scale Kennedy spending.

Bonn Brown of Elkins was the personal attorney to W. W. “Wally” Barron, who was elected Democratic governor of West Virginia in 1960. He estimated the Kennedy outlay at between $3 million and $5 million, with some sheriffs being paid as much as $50,000. Asked how he knew, Brown told me curtly, “I know. If you don’t get those guys”—the sheriffs—“they will really fight you.” In his role as adviser to the Democratic gubernatorial candidate, Brown met with Robert Kennedy and other campaign officials “and told them who to see and what to do, but stayed clear of it myself. Bobby was smart and mean as a snake. I think he had more to do with West Virginia”—the victory there, and the payoffs—“than any other person. Bobby ran it; he was the one who set it up.” Governor Barron was later convicted on bribery charges, and Brown was later convicted of the attempted bribery of a juror in the case.

Curtis B. Trent, of Charleston, who served as executive assistant to Governor Barron, also recalled that the Kennedys “were spreading it around pretty heavy. I thought they spent two million dollars.” Trent, like Bonn Brown, insisted that he did not personally take any Kennedy money. “They were trying to push it off on us,” he recalled. “I’d explain to them that I was concerned with the governor’s race and not the president’s race.” Kennedy reacted typically to Trent’s refusal to help: “Bobby was so mad … just as angry as he could be.” Trent, like more than a dozen officials of the Barron administration, the most corrupt in the history of the state, was convicted of income tax evasion and sentenced to a jail term in 1969.

The Gabriel, Brown, and Trent accounts are buttressed by Rein Vander Zee, a former FBI agent who had been working since early January 1960 in Humphrey’s West Virginia campaign. Vander Zee was responsible for dealing with the sheriffs of West Virginia, and had—for a price—received their political commitments for Humphrey. “Four or five days before the primary,” Vander Zee, now living in Bandera, Texas, told me in an interview in 1995, “I couldn’t get some of my people on the phone. I said, ‘Oh, my God,’ and got in my car and started driving. They were laying out—the sheriffs—and I knew something was way wrong. The Humphrey signs were down and Kennedy signs were up. I met Sid Christie, who was supposed to be our man [in McDowell County] all the way. He was the absolute boss down there.” Vander Zee arranged a meeting with Christie in the rural town of Keystone. “We sat in his car across from a deserted movie theater, like a scene from The Last Picture Show. I said, ‘What can be done?’” Christie dryly responded: “It’s too late. I didn’t realize what a groundswell of support there’d be for this other fellow.”

Vander Zee said he and Humphrey later held a last-ditch conference with Wally Barron, the governor-to-be: “We asked him what had to be done. I always liked Wally.” Barron gave Humphrey the bad news: he was being vastly outspent by the Kennedys. “He said he had a figure [of Kennedy expenditures] that was something we couldn’t meet,” Vander Zee said. Years later, a West Virginia political professional told Vander Zee that he watched as Christie received a huge payoff from a Kennedy insider—at least $40,000, the professional said—“in green in a shoe box.” Kennedy received 84 percent of the Democratic primary vote on May 10 in McDowell County.

In the years after Kennedy’s assassination, many people would take credit for his strong showing in West Virginia.

In his autobiography, The Education of a Public Man, published in 1976, Hubert Humphrey told of a 1966 meeting with Richard Cardinal Cushing, the archbishop of Boston, in which Cushing expressed anger at what he called the self-aggrandizement of various Kennedy aides, such as Ted Sorensen. “I keep reading these books by the young men around Jack Kennedy and how they claim credit for electing him,” Cushing told Humphrey. “I’ll tell you who elected Jack Kennedy. It was his father, Joe, and me, right here in this room.” Humphrey and an aide sat in stunned silence as Cushing told how he and Joe Kennedy had agreed that West Virginia’s anti-Catholicism could be countered by a series of cash contributions to Protestant churches, particularly in the black community. Cushing continued, Humphrey wrote: “We decided which church and preacher would get two hundred dollars or one hundred dollars or five hundred dollars.”

The most widespread misinformation about the West Virginia election involves the role of organized crime, which, according to countless magazine articles and books over the past thirty years, supplied the cash that enabled Kennedy to win. The allegations center on Paul “Skinny” D’Amato, the New Jersey nightclub owner who in 1960 became general manager of a Nevada gambling lodge owned in part by Frank Sinatra and his good friend Sam Giancana of Chicago. D’Amato’s account, as repeatedly published, is that he was approached by Joe Kennedy during the primary campaign and asked to raise money for West Virginia. D’Amato agreed to do so, with one demand: if Jack Kennedy was successful in gaining the White House, he would reverse a 1956 federal deportation order for Joey Adonis, the New Jersey gang leader. With Joe Kennedy’s promise, D’Amato raised $50,000 for West Virginia from assorted gangsters. D’Amato, who died in 1984, has been quoted as telling a business associate that the $50,000 was used not for direct bribes but to purchase desks, chairs, and other supplies needed by local politicians. After Kennedy’s election, D’Amato said, he reminded Joe Kennedy of his pledge. The father explained that the Adonis deal was fine with his son the president, but Bobby, the new attorney general, wouldn’t hear of it. There is no basis for disbelieving D’Amato’s account; but $50,000 in cash, when contrasted with what was really spent in West Virginia, was hardly enough to earn everlasting gratitude from the Kennedys.

D’Amato’s big mouth got him in trouble. Soon after taking office, Bobby Kennedy was informed by the FBI that D’Amato had been overheard on a wiretap bragging about his role in moving cash from Las Vegas to help Jack Kennedy win the election. A few months later, D’Amato suddenly found himself facing federal indictment on income tax charges stemming from his failure to file a corporate tax return for his nightclub. The indictment was brought to the attention of Milton “Mickey” Rudin, a prominent Los Angeles lawyer who represented Frank Sinatra and other entertainment figures.

“Skinny [was] Frank’s friend,” Rudin told me in a series of interviews for this book. “Bobby [Kennedy] and the Old Man [Joe Kennedy] knew the relationship. When Skinny got indicted, I got pissed and called up Steve Smith. I tell him I want to see him. He meets me at the University Club in New York. I order my gin. ‘What can I do for you?’ Smith asks. I tell him, ‘I’m unhappy about Skinny being indicted on the bullshit charges. It’s unfair. No taxes were paid because there was no profit.’” Rudin said he did not raise the issue of D’Amato’s political favors for the Kennedy campaign, but he did tell Smith, “This is a political act.” Smith responded, “Well, you don’t understand politics.” Rudin then said, “Well, I’m glad I don’t,” drank his gin, and left.

Steve Smith delivered a clear message, Rudin said: D’Amato had been overheard on FBI wiretaps talking about Las Vegas cash going to the Kennedys, and the indictment neutralized any possible damage from such talk. “If some guy like Skinny had anything to do with moving money,” Rudin concluded, “the way to handle him is to indict him so if he talked about it, it’d be [seen as] vengeance.” Rudin told me that he returned to Los Angeles thinking—and saying as much to Sinatra and others—that the Kennedys were going to be much tougher than some had thought.

Organized crime, as we shall see, played a huge role in Kennedy’s narrow victory over Richard Nixon in November. But Jack Kennedy had more than a few campaign promises to gangsters to worry about, both before and after the election.

* Max Kampelman, Humphrey’s longtime friend and political adviser, recalled warning Humphrey not to run against Kennedy in West Virginia. In an interview in 1994, Kampelman said he “knew” that the Kennedys would put big money into the state and “steal the election—and we had no money.” An additional concern was Humphrey’s political future: “I told Hubert, ‘They’ll [the Kennedys will] kill you in West Virginia, and you have to run for reelection [to the Senate] in Minnesota. They’ll paint you as anti-Catholic, and there are a lot of Catholics in Minnesota.’” Humphrey nevertheless won reelection to the Senate in 1960.