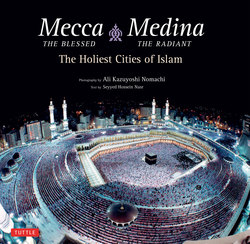

Читать книгу Mecca the Blessed & Medina the Radiant (Bilingual) - Seyyed Hossein Nasr - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIn the Name of God, the Infinitely Good, the All-Merciful

The Holiest Cities of Islam

“And this is a Book which We have sent down full of blessings and confirming what [was revealed] before it: that thou mayest warn the Mother of Cities [Umm al-qura—Mecca] and its surroundings. Those who believe in the hereafter believe herein and they are constant in their prayers.”

—Qur’an, vi: 92, trans. Yusuf Ali, modified

“Medina is best for them if they only knew. No one leaves it through dislike of it without God putting in it someone better than he in place of him, and no one will remain there in spite of its hardship and distress without my being an intercessor on his behalf on the day of resurrection.”

—Saying (hadith) of the Prophet of Islam, in Muhammad ibn Abd Allah Khatib al-Tibrizi, Mishkat al-Masabih, trans. James Robson, Lahore: Muhammad Ashraf, 1981, pp. 586–7

Two events, which in fact are two aspects of the same reality, cast the cities of Mecca (Makkah) and Medina (Madinah) in a short period upon the pages of world history. These events were the birth in AD 570, the maturity and prophethood of Muhammad ibn Abd Allah—peace and blessings be upon him—and the descent of the Qur’anic revelation upon him during a 23-year period from 610 until his death in 632. These events of cosmic proportions established Islam, the last plenary religion of humanity, upon the earth, thereby transforming not only the history of Arabia or of the Mediterranean basin and the Persian and Byzantine Empires, but also of lands as far away as France and the Philippines and, ultimately, the whole of the globe. The revelation of the Noble Qur’an, the verbatim Word of God for Muslims, began in Mecca where the Blessed Prophet was born and continued in Medina where he died. The very landscape of these two cities still reverberates with the grace (barakah) of the revelation and echoes the presence of that most perfect human being who was chosen by God to receive His last message and thereby to bring to completion the cycle of prophecy which had begun with Adam himself.

Mecca the Blessed (al-Makkat al-mukarramah) and Medina the Radiant (al-Madinat al-munawwarah), as they are known to Muslims, became intertwined by the very events of the Islamic revelation. Mecca, the city where the primordial Temple and House of God, the Ka’bah, is situated, was where the Prophet was born and raised while Medina became his city by virtue of his migration there in AD 622, which marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar. The very name Medina, which in Arabic means simply “city”, is, in fact, the abbreviation of Madinat al-nabi, “the City of the Prophet”, which replaced the older name of Yathrib after the Blessed Prophet migrated to that city where he established the first Islamic community and the first mosque.

The testimony whereby a person embraces Islam is simply “la ilaha illa’Llah” (there is no divinity but Allah) and “Muhammadun rasul Allah” (Muhammad is the messenger of God), “Allah” being simply the Arabic word for God considered in His absolute Oneness beyond all hypostatic differentiations. These two formulas are inseparable in Islamic life and are seen by Muslims as being inwardly united. One may say that such is also the case of Mecca and Medina, the two holy centers of Islam, whose significance is inseparable in the religious life and thought of Muslims. Mecca is primarily the city of God by virtue of the Kab’ah and may be said to correspond to “la ilaha illa’Llah”, while Medina, where the Mosque of the Prophet and his tomb are to be found, is of course primarily the city of the Prophet and corresponds to “Muhammadun rasul Allah”. And in the same way that five times a day the call to prayer (al-adhan), heard from minarets and rooftops as well as in streets and houses throughout the Islamic World, announces the two testimonies of faith together, the barakah and significance of those holy cities remain organically united. At the same time, their influence, and the second by virtue of the first, has over the centuries dominated not only the heart-land of Islam in Arabia but all Islamic lands near and far, and love for them is cherished in the hearts of men and women of all different races and climes where there has been a positive response to the call to unity (al-tawhid) of the Islamic message.

The Arabian Peninsula

The peninsula of Arabia is located at the crossroad of three continents, Asia, Africa and Europe, its northern regions neighboring the Mediterranean world, its eastern realms Persia, and its southern shores Africa, with which it has always enjoyed close links in trade, migration of ideas and also people, as it has with its other neighbors. The southern region of the peninsula, home to ports through which goods were brought from the Indian Ocean, has always been more green than the north and was the home of many ancient civilizations. Its people, who considered themselves descendants of Qahtan, became known for the wonderful plants and perfumes that they cultivated. The frankincense and myrrh of southern Arabia were so well known in the Roman Empire that the Romans called this region Arabia Odorifera. It is sufficient to think of the Queen of Sheba and her world to recall the great regard that peoples of antiquity held for the high civilizations of southern Arabia.

As for the northern part of the peninsula, it was adjacent to the great Semitic civilizations of Mesopotamia, the influence of whose art is to be seen in the artifacts found in the north. Later, there were also close contacts with the Persian and Byzantine Empires. In the centuries between the rise of Christianity and the advent of Islam, there were, in fact, local kingdoms in the north such as the Nabataean and the Ghassanid which exercised influence upon certain aspects of the cultures of Arabia, the latter having been Christian.

The heartland of Arabia, consisting of Hijaz and Najd, continued, however, to be dominated mostly by Arab nomads who had remained on the margin of the major historical developments to their north and were not greatly influenced by either Judaism or Christianity despite the presence of members of both communities in the cities of Arabia. As far as Hijaz, the sacred land in which Mecca and Medina are located, is concerned, it is the name of the western region of the Arabian peninsula, consisting of a fairly narrow tract of land about 1,400 kilometers long east of the Red Sea with the Tropic of Cancer running through its center. The land is called Hijaz, meaning “barrier”, because its back -bone, the Sarat Mountains, running parallel to the Red Sea, separates the flat coastal area called Tihamah from the highlands of Najd. The Sarat Mountains consist of volcanic peaks and natural depressions, creating a stark and rugged environment dominated by intense sunlight and with little rain. And it is in one of the natural depressions of this mountain range that is to be found the sacred city of Mecca, the hub of the earth and its center for the descendants of Ismail (the biblical Ishmael).

Arabia is dominated by deserts that before modern times could not be crossed except with the help of camels which, therefore, became indispensable to the life of its people. The population centers have always been situated around wells and springs in the desert which have created the oases for which certain desert areas are well known. The majority of the population of Arabia consisted of nomads, although cities such as Mecca existed in Arabia even before the rise of Islam. It was, however, only during the twentieth century that the vast majority of the nomads of Arabia became sedentarized and attempts were made to use the vast underground water sources of the peninsula to create agriculture for the settled nomads. Throughout history, the Arabs, the descendants of lshmael (Ismail), were mostly nomads of Semitic stock. Something essential of the spiritual dimension of Semitic nomadism was, in fact, adopted by Islam and has therefore become a basic aspect of the spiritual universe of all Muslims.

Masjid al-Haram, the Grand Mosque of Mecca, a hundred years ago. In this photograph, the sacred spring Zamzam is located in a peak-roofed building adjacent to the Ka‘bah. Today, the buildings in close proximity to the Ka‘bah have been demolished and access to the spring of Zamzam has been moved underground.

Masjidil Haram, Masjid Raya di Mekkah, yang dipotret seratus tahun yang lalu. Di foto, tampak mata air suci Zamzam terletak di bangunan beratap pelana di sebelah Ka’bah. Sekarang, bangunan dekat Ka’bah itu telah diruntuhkan dan pintu masuk menuju mata air dipindahkan ke bawah tanah.

Mecca’s Early Sacred History

From the Islamic point of view, Mecca, the Ka’bah and the environs of the holy city are associated with the very origin of humanity and Islam’s sacred history which, being based on the chain of prophecy, begins with Adam himself. The spiritual anthropology of Islam stated in the Qur’an begins with the creation of Adam and Eve in Paradise, their subsequent fall, which is not, however, associated with original sin in the Christian sense, and their search for each other on earth. Traditional sources mention that Adam descended in the island of Sarandib, or present-day Sri Lanka, and Eve in Arabia. Adam then set out to find Eve and finally encountered her at the plain of Arafat, so central to the rite of the annual pilgrimage to this day. Here, the two halves of primordial man, in the sense of anthropos and not only the male, became united again, and therefore it is here that one must search for the origin of the human family. It was also in this area in Mecca, then called Becca (Bakkah or “narrow valley”), that Adam built the first temple, the Ka’bah, as the earthly reflection of the Divine Throne and the prototype of all temples. Adam is said to have died and been buried in Mecca and Eve in Jeddah by the sea which still bears her name, Jiddah, meaning “maternal ancestor” in Arabic. The area of Mecca with the Ka’bah at its heart is therefore associated with primordiality, essential to Islam which considers itself as the reassertion of primordial monotheism and addresses what

is primordial in the human soul, hence its also being called din al-hanif (the primordial religion) and din al-fitrah (the religion of one’s primordial nature).

Nor are the main later stages of Islamic sacred history separated from the area of Mecca. According to tradition, when the flood occurred, the body of Adam, which had been interred in Mecca, began to float on the water while the ark of Noah circumambulated around it and the Ka’bah seven times before setting out north where it landed after the flood. A thousand years later, the great patriarch of monotheism, Abraham, or Ibrahim, came to Mecca with his Egyptian wife Hagar (Hajar) and their child Ishmael (Ismail). It was he who discovered the mount left after the flood underneath which lay God’s first temple built by Adam. And it was there that Abraham set out to rebuild the Ka’bah, which in its present form owes its origin to him.

Map of the center of Medina, dated 1790, when the city was surrounded by ramparts with the Mosque of the Prophet at its heart. The ramparts seen here, 2,300 meters long with four gates, were completed in 948/1541.

Peta dari pusat kota Madinah ditahun 1790 dimasa ketika kota ini dikelilingi dinding tinggi dengan Masjid Nabawi berada di jantungnya. Dinding pertahanan yang terlihat disini, dengan panjang keseluruhan 2,300 meter dengan empat gerbang, selesai dibangun pada tahun 948 H (1541 M).

Leaving his wife and child with some water and dates, Abraham left Mecca on God’s command. Hagar suckled her son and they drank the remaining water. Soon, however, both faced great thirst and the child began to cry. Hagar began to run between two mounds named Safa and Marwah looking for water, repeating the journey seven times until an angel appeared to her, striking the ground with his wing, with the result that the spring of Zamzam, which Muslims consider as a “tributary” of the water of Paradise, gushed forth. Henceforth, Mecca was to be blessed with a source of water which has continued to this day. It was because of the Zamzam that the Jurhum tribe from northern Yemen came to settle in Mecca where they adopted Ishmael (Ismail), taught him Arabic and made him one of their own.

Muslim historians also believe that it was at Mount Thabir, situated north of the Mecca valley, that Abraham, upon returning to Mecca, took Ishmael (Ismail) to be sacrificed for God. In the Islamic version of the binding of the son of Abraham, the son himself was perfectly resigned to the Will of God as was the father. “So when they both surrendered [to Allah] and he had flung him upon his forehead We called out to him: ‘O Abraham! Thou hast already fulfilled the vision.’ Lo! Thus do We reward the good.... Then We ransomed him with a tremendous sacrifice. And we left for him among the later folk (the salvation): ‘Peace be upon Abraham!’ ” (Qur’an, xxxvii: 103–9). This great episode of sacred history, shared in different versions by Jews, Christians and Muslims alike, is thus again associated by the Muslim mind with the area of Mecca.

It was after this event and the departure and return of Abraham to Mecca that the most lasting mark of the Patriarch in Mecca was created. Upon his return, Abraham discovered that his wife Hagar had died. Then he called upon his son Ishmael (Ismail), who is called “the father of the Arabs” and was the ancestor of the Prophet of Islam, to help him in the construction of the House of God, bayt al-atiq or the “Ancient House” as the Arabs called it. The Divine Peace (al-sakinah) descended in the form of a wind which brought a cloud in the shape of a dragon that revealed to them the site of the old temple. Abraham and Ishmael (Ismail) dug the ground until they discovered with awe the ancient temple built by Adam. A stone came to light on which there was the following inscription: “I am the God of Becca. I have created compassion and love as my two appellations. Whoever attains these virtues shall meet Me. And whoever removes himself from these virtues is removed from Me.” Already Allah, whose Name is inseparable from the qualities of compassion and mercy in Islam and who was to reveal “Bismi’Llah al-Rahman al-Rahim” (In the Name of God, the Infinitely Good, the All-Merciful) as the formula of consecration in the Noble Qur’an, had spoken. And He had spoken at the place that was to become inseparable from the celebration of His Names of Rahman and Rahim from the advent of Islam.

Abraham or Ibrahim, known in Islam also as Khalil Allah or Friend of God, built the Ka’bah as a sign of his perfect faith in his Friend. Thus does the Qur’an address him: “Associate naught with Me and purify My house for those who make the round (thereof) and those who stand and those who bow and make prostration. And proclaim unto mankind the Pilgrimage” (Qur’an, xxii: 26–7).

He made the first pilgrimage with his son Ishmael (Ismail), and in the presence of the archangel Gabriel performed all the elements which constitute the rite of Hajj today. Under Divine Command, he established a rite which was revived by the Prophet of Islam and which is inseparable from the reality of Mecca and its meaning for Muslims the world over to this day. Abraham was to leave Mecca to die in Palestine in al-Khalil, but he left an important part of himself and his heritage in Mecca. And so Abraham raised his hands in prayer and said according to the Noble Qur’an: “Our Lord, I have settled a part of my offspring in an infertile vale near Thy Sacred House, our Lord! That they may establish proper worship” (Qur’an, xiv: 37). Henceforth, Mecca became inseparable from Abrahamic monotheism, and despite the rise of Arabian paganism in later centuries in that city, it was finally here that the religion of the One was re-established in its final form with the advent of Islam. Mecca’s sacred history links it therefore inalienably to the message and heritage of Abraham, whose progeny continued to live there. Eventually, they gained power over the city and finally, as a result of their indulgence in idolatry, lost that power because of the revelation of the message of the One to one of their own, namely, Muhammad—may blessings and peace be upon him—who destroyed the idols and renewed fully the monotheism of his ancestor Abraham.

The Protohistory of Arabia and the Holy Cities

Already in an inscription of the Assyrian King Salmanazar II, dating from 854 BC, there is reference to the “Arabs”, probably meaning “desert dwellers”. The Arabs were Semites who, with the help of camels, were able to navigate the Arabian peninsula around 1000 BC while creating settlements such as Aram and Eberin in the north of the peninsula. Divided into tribes, they guarded jealously their genealogy and tribal customs, and until the advent of Islam their allegiance was first and foremost to their tribe while intertribal skirmishes and warfare characterized their lives. Some of these tribes remained in a particular region while others, such as the Amaliq, mentioned in the Bible as the Amale-kites, were to be found throughout the Arabian peninsula.

It was a branch of this tribe, known as the Abil, that founded the city of Yathrib, later to be known as Medina. Blessed by much underground water, the plain of Yathrib, lying between the ranges of the Sarat Mountains, became the site of a prosperous community. But its people disobeyed God and so were punished by natural calamities such as pestilence, and also the Prophet Moses sent an army to punish them. Centuries later, Jews, probably fleeing from Nebuchadnezzar, migrated to Yathrib and formed the community whose descendants the Prophet of Islam was to meet upon his migration to that city.

According to Arab custom going back to the earliest known historical period, it was forbidden to fight in the vicinity of the Ka’bah. Another branch of the Amaliq, taking advantage of the fact that the descendants of Ishmael (Ismail), the custodians of the Ka’bah, would not engage them in battle there, attacked them and drove them out. The descendants of Ismail took refuge in the gorges around Mecca as nomads, some wandering to other parts of Arabia and others remaining close to the House of God erected by their ancestors Abraham and Ishmael (Ismail). Gradually, Mecca grew in stature as the chief sanctuary of Arabia, and tribes would come from every corner of the peninsula to pray in and around the Ka’bah, which had by now become defiled, from the Islamic point of view, with idols of various tribes, the original significance of the structure as the House of the One God eclipsed and forgotten by the majority save the few who, however, remained attached to Abrahamic monotheism and whom Islam calls the hunafa or “primordialists”. It was also as a result of the presence of these idols that Jews ceased to visit the Ka’bah. The structure of the Ka’bah remained unchanged, however, and it was rebuilt exactly as it was before by the Amaliq after a flood inundated and destroyed it. What changed over the centuries was that floods brought sedimentation from adjacent hills, which raised the ground around the Ka’bah to such an extent that the original mound upon which Abraham had built the Ka’bah was no longer visible.

It was the victory of the Jurhum tribe from the Yemen over the Amaliq and their conquest of Mecca that accentuated polytheism in the Sacred City. But they were, in turn, defeated by the Khuza’ah, an Arab tribe of Ismailite descent, which had migrated to the Yemen and then returned north. The Amaliq did not leave Mecca, however, without seeking to ravage it, including among their actions the burial of the spring of Zamzam. In entering Mecca, the Khuza’ah continued to protect the city as a center of pilgrimage for the Arab tribes, and themselves brought the famous idol Hubal, which they placed within the Ka’bah and which they made the chief idol of Mecca.

The Quraysh, the Hashimites and the Birth of the Prophet

Around the fourth or fifth Christian century, another Ismailite tribe, the Quraysh, one of whose members was to be chosen as the final prophet of God, began to gain ascendance in Mecca. One of their members, Qusayy, married the daughter of the chief of the Khuza’ah tribe and later became the ruler of Mecca and custodian of the Ka’bah. He ruled over both the Quraysh who lived near the sanctuary and those farther away. He was a capable ruler and it is said that it was he who built the city of Mecca in the form of concentric circles around the Ka’bah with the inhabitants of each circle being determined by their social rank, with those of higher rank living closer to the “Ancient House”. This original plan of the city lasted into the historical period and traces could be found until the advent of the urban development of recent decades.

The grandson of Qusayy was named Hashim, after whom the clan of the Prophet, the Hashimite, is named. Hashim was also a competent ruler and succeeded in making Mecca prosperous by expanding trade routes through the city. He married Salma, one of the most influential women of Yathrib of the tribe of Khazraj, and from this union was born Shaybah. Brought up originally by his mother in Yathrib, he was taken to Mecca upon the death of his father by his uncle Muttalib. Since he was riding behind his uncle in entering the city, he was called in error Abd al-Muttalib (the slave of Muttalib), a name with which he came to be identified. This remarkable figure of great spiritual stature and statesmanship finally became the ruler of Mecca.

Prayers in the evening of Laylat al-Qadr, normally celebrated on the 27th of Ramadan.

Sholat di malam Laylatul Kadar, biasanya dirayakan pada tanggal 27 Ramadhan.

Once, while sleeping by the area adjacent to the Ka’bah known as Hijr Ismail, he dreamt that he should dig for the spring of Zamzam buried long before by the Amaliq. The dream occurred twice, and so Abd al-Muttalib began to circumambulate the Ka’bah. After completing this ancient ritual, he saw a number of birds strutting to a place a hundred yards away from the Ka’bah. And so he began to dig in that spot to which he was led by the sign from Heaven. Soon, the long-lost spring of Zamzam gushed forth as if foretelling of the reassertion of primordial monotheism and the reconsecration of the Ka’bah to the One in the near future. The tribe of Hashim was given the right of supervision over the water of the Zamzam, a privilege whose significance can hardly be overemphasized.

Abd al-Muttalib had vowed that if he were to have ten sons, he would sacrifice one of them to God to whom he, as a hanif, always prayed, never bowing before the idols of Mecca. After the drawing of lots, Abd Allah, his most beloved son, was chosen for sacrifice but his mother, Fatimah, from the powerful Makhzum tribe, was opposed to this act. After much consultation and prayer, Abd al-Muttalib agreed to sacrifice a hundred camels instead. The future father of the Prophet of Islam was thereby saved and Abd Allah who, because of his physical beauty was called the Joseph of his time, was married in 569 according to his father’s choice to Aminah, a descendant of the brother of Qusayy.

There lived at that time a hanif in Mecca by the name of Waraqah who had become a Christian. A holy man in touch with other Christians of the region, he declared that the coming of a new prophet was imminent. The rabbis had also believed in this news but they considered the new prophet to be a descendant of Isaac while Waraqah thought that he could be an Arab. Before the marriage ceremony, as Abd Allah and his father Abd al-Muttalib were walking toward the place where the ceremony was to take place, the beautiful and pious sister of Waraqah, Qutaylah, was standing at the door of her house. She saw Abd Allah and became startled by the light in his face which she knew to be the light of prophecy. She offered herself in marriage to him for the hundred camels that were sacrificed by his father in his place, but Abd Allah could not disobey his father and therefore refused the offer. After the consummation of the marriage, the next day when Abd Allah saw Qutaylah again she showed no interest in him, and when he asked the cause she said that the light in his face had disappeared. That light was to manifest itself in the being of the child who was conceived the night before. But Abd Allah did not live long enough to see his son Muhammad, who was born in the Year of the Elephant, that is 570, as an orphan.

That year was indeed a momentous one for Mecca, Arabia and ultimately most of the world. The Christian ruler of Abyssinia, Abrahah, had conquered the Yemen and built a cathedral in San’a with the hope that this monument would replace Mecca as the center of religious activity in Arabia, but the cathedral was defiled by a member of the Kinanah tribe who managed to escape to safety. Abrahah thus decided to take revenge upon Mecca by razing the Ka’bah to the ground. He assembled a vast army with an elephant leading in front. Approaching Mecca, he asked for the leader of the Quraysh to come out to meet him, saying that he had nothing against the people of the city but wanted only to destroy the Ka’bah. Abd al-Muttalib came out to meet him, and to the great surprise of the latter did not ask for the Ka’bah to be saved but only for his camels, taken by Abrahah’s soldiers, to be given back. When Abrahah asked why this was his only demand, Abd al-Muttalib said that he was responsible only for his camels and that the Lord of the Ka’bah would take care of his own House. Abd al-Muttalib then returned to the Ka’bah, asking God for help and then left with all the Meccans to the adjacent hills.

Abrahah then decided to march upon Mecca, but near the city the elephant in front of the army refused to move and simply sat on the ground. No amount of beating could change its will. Suddenly, the sky turned black and a cloud of birds appeared, which pelted the army, killing most of the soldiers, the rest fleeing back to the Yemen. Hence the year, so famous in Islamic sources, became known as the Year of the Elephant. As a result, Mecca, which was soon to enter into the full light of history, was saved and the Quraysh gained greater respect among the other tribes as the people of God because their prayers were answered.

The momentous nature of this year was not only, however, in the miraculous saving of the Ka’bah, but most of all in the birth of the person who, forty years later, would be visited by the archangel Gabriel in Mecca and who would rid the Ka’bah of all the dross of forgetfulness of the One which, over the centuries, had covered its original face. Muhammad ibn Abd Allah—upon whom be blessings and peace—was born to Aminah in Mecca and was given this name by God’s command. His grandfather, Abd al-Muttalib, took the new-born child immediately to the Ka’bah where he offered prayers to God. Thus, the life and later message of the Prophet became intertwined with the Ka’bah from the earliest moments of his earthly life and a link was established which, according to Islam, will last until the Day of Judgement.

The Prophet in Mecca and Medina

The life of the Prophet of Islam was spent nearly completely in the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina where his barakah is ubiquitous for pious Muslims to this day. It was in Mecca that he was nurtured and raised, while spending some time in the care of the nomadic tribes in the areas around the city as was the tradition of the time. It was in Mecca that he gained fame as a just and trustworthy person and was bestowed with the title of al-Amin, the Trusted One, even before being chosen as prophet. It was in this city that he married Khadijah and where his children were born. In fact, the foundations of his house were visible in Mecca until the recent expansions of the Great Mosque. It was from here that he led the caravans of Khadijah, his wealthy and faithful wife, to Syria and back. It was in the hills around this city that he took refuge to be alone with God, and it was on the top of one of these hills, al-Hira, which stands just outside today’s Mecca, that in the year 610 he was visited by the archangel Gabriel and the first verses of the Noble Qur’an were revealed to him.

The advent of the revelation, of course, transformed the life of the Prophet completely, placing upon his shoulders the responsibility of establishing God’s religion based upon the doctrine of Divine Unity (al-tawhid) amidst a society given to idolatry and in a tribe which derived its power from idol worship. Although his message was accepted immediately by his beloved wife Khadijah, trusted friend Abu Bakr, and intimate cousin and future son-inlaw Ali, it was in the middle of his own city of Mecca that the Prophet was to encounter the most severe challenges, opposition, humiliation and threats, and experience the bitterness of being the object of enmity of so many of the members of his own Quraysh tribe. But also it was here that he persevered and succeeded in creating the nucleus of the first Islamic society.

It was also from the blessed city of Mecca that God chose to have him ascend during the Nocturnal Journey (al-miraj) with the help of the archangel Gabriel, from Mecca to Jerusalem and from Jerusalem to the Divine Throne. Jerusalem was the first direction of prayer for Muslims (al-qiblah al-ula) and then, while the Prophet was in Mecca, God ordered that city to become the qiblah. The miraj reconfirmed for all later generations of Muslims the spiritual connection between Jerusalem and Mecca, the first and second qiblah and the center of monotheism as a whole and Islamic monotheism respectively; two cities whose spiritual reality will, according to Islamic teachings, become reunited at the end of time, while being deeply interconnected here and now.

The Prophet was to leave a Mecca in deep enmity against him, where even his life was now threatened, for the hospitality of the city which was to take his name and become known as the City of the Prophet, Madinat al-nabi. He was to return to his city of birth several years later to perform the pilgrimage in peace and finally to enter Mecca in triumph in the moment which marked the crowning achievement of his earthly life. He was to order Ali and Bilal to rid the Ka’bah of the idols of the Age of Ignorance (al-jahiliyyah) and to re-establish it as the primordial temple dedicated to the One God. His final departure from Mecca left that city as the unquestionable center of the new religious universe created by the Qur’anic revelation. At once the site of the Ka’bah, the birthplace of the Prophet, the place of the first revelation of the Qur’an and the qiblah of all Muslims, Mecca thus became and remains the holiest of Islamic cities.

It was, however, the city of Yathrib to the north that opened its arms to the Prophet at a moment when his life and that of the nascent Islamic community were threatened by the intractable enmity of the Quraysh in Mecca. The Prophet thus set out with his trusted companion Abu Bakr for what was to become Medina, having sent his followers, known as al-muhajirun, literally “the immigrants”, in small groups before him to that city with a few to follow afterwards. It was at the outskirts of Medina, at the site of the present Quba Mosque, where he performed his prayers. It was to the present site of this mosque that his camel was to take him—by its own will so as to avoid contention between different groups that wanted to offer him hospitality at their homes.

Medina was integrated by the Prophet into the first fully fledged Islamic society, to become henceforth the model for all later Islamic societies. The Prophet had a Constitution prepared for the city which is the earliest Islamic political document. Here, he established norms which were to become models for later Islamic practice and promulgated laws which became foundational to Islamic Law or al-Shari’ah. While the revelation continued in Medina, the community became transformed from a small number of scattered adherents to a fully organized society, the heart of a vast religious universe which was in the process of formation. But the challenge of Meccan forces against Islam continued and Medina and its environs were witness to crucial battles which decided the fate of the new community. The first great battle (al-ghazz) was al-Badr, in which a vastly outnumbered Muslim army overcame the Meccan army with the help of angels, according to traditional sources, at a site just outside of Medina. The battle of Uhud, in which the Muslims were defeated and the Prophet injured without the Meccans pursuing their victory, likewise took place close to the present limits of the city, while the site of the battle of Khaybar, in which Ali showed exemplary valor, is not far away. Medina was even besieged once and saved only by the wise decision of Salman al-Farsi, the first Persian to embrace Islam, to dig a ditch around the city, hence the name of the battle as al-Khandaq or “the Ditch”.

The wilderness stretching to the north of Medina forms a striking contrast to the desert area lying at the center and east of the Arabian peninsula. The Hijaz region, in which both Mecca and Medina are located, has mountains extending both north and south, some continuing to be volcanically active.

Gurun membentang di utara Madinah menyajikan pemandangan jauh berbeda terhadap padang pasir yang terhampar di sisi tengah dan timur jazirah Arab. Wilayah Hijaz tempat kota Mekkah dan Madinah berada memiliki pegunungan yang memben-tang ke utara dan selatan. Beberapa gunung berapi masih tampak aktif.

It was in and around Medina that both successes and failures took place militarily as well as socially and politically, but while the failures were shortlived and overcome by never-ending hope and reliance of the Prophet upon God, the successes increased and the strength of the Islamic community augmented from day to day until gradually all of Arabia became united under the banner of Islam during the lifetime of the Prophet, with Medina serving as the sociopolitical capital and center of this newly integrated world. The man who rode with his close friend Abu Bakr from Mecca to the city of Yathrib became within a decade in that city, which had now become Medina, the prophet-king of the whole of Arabia and the founder of a new religious civilization and society whose boundaries were to stretch in less than a century from China to France. And it was to this city, in which God had bequeathed upon him the mastery and dominion of a whole world, that he returned from his city of birth, Mecca, to spend the last few months of his life. Furthermore, it was there in Medina that he died in 10/632 to be buried in his own apartment next to the mosque which he had ordered to be built, the Masjid al-nabi or Mosque of the Prophet, that is the prototype of all later mosques. Medina, therefore, became the second sacred city of Islam, reflecting to this day, and despite the loss in recent years of much of its traditional architecture and palm groves (some planted by Ali and other companions of the Prophet), crucial stages in the life of the Prophet, his family and companions. One can still sense the perfume of his presence in that beautiful oasis city, al-Madinah, which Muslims cherish the world over.

Mecca and Medina in Later History

Through all the later vicissitudes of Islamic history, Mecca and Medina have continued as the spiritual and religious centers of the Islamic world, but the political heart of the Islamic world was to leave Arabia a little more than two decades after the death of the Prophet. Abu Bakr, Umar and Uthman, the first three caliphs, ruled the ever-expanding Islamic world from Medina, where they enlarged the Mosque of the Prophet as well as the limits of the city itself. But the fourth caliph, Ali, facing the rebellion of the garrison in Syria, moved to Kufa in Iraq to prepare an army to put down this revolt. His coming to Kufa, which henceforth became the capital until Ali’s assassination, moved the political center of Islam out of Arabia forever. For after Ali, the Umayyads who gained political power did not return to Mecca or Medina but made Damascus their capital while their successors, the Abbasids, built Baghdad as their capital. Both dynasties, however, influenced the architecture of the two holy cities. During the early Umayyad period, the people of both Mecca and Medina resisted strongly Umayyad directives. The grandson of Abu Bakr, Abd Allah, led a revolt in Mecca against the Umayyads, as a result of which the Ka’bah became seriously damaged and was rebuilt with the help of architects and craftsmen using Yemeni building techniques. But the city was attacked again by the Umayyad general al-Hajjaj and all of Abd Allah’s work on the Ka’bah was destroyed and the monument reconstructed. Likewise in Medina, many of the houses of the ahl al-bayt or household of the Prophet, including the house of Fatimah, were destroyed by the Umayyads. Some people believe, in fact, that the Umayyads built the monumental mosques of Jerusalem and Damascus so that Muslims would pay less attention to Mecca and Medina, but such was not to be the case.

Although raids and skirmishes continued from time to time, the most famous being that of the Carmathians in the fourth/tenth century during which they stole the Black Stone of the Ka’bah for twenty-one years, Mecca and Medina continued to be revered as the spiritual centers of the Islamic world. They even resisted the more worldly art that the Umayyads had developed farther north and had sought to impose upon the two holy cities. During the Abbasid as well as Mamluk and Ottoman periods, great attention continued to be paid to the two cities and many fine monuments were created, some of which survive to this day, for it was the greatest honor and responsibility to be custodian and protector of the two holy cities. Since 1926, after the demise of the Ottoman Empire and the defeat of the Hashimites of Mecca by the Saudis, Hijaz has been a part of Saudi Arabia. Under the new situation, the custodianship of the two holy cities continued to be seen as the greatest honor by the Saudis to the extent that the King of Saudi Arabia is not referred to as “His Majesty” but as “Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques”.

During all the centuries of Islamic history, Mecca and Medina remained outside the major turmoils in the heartland of the Islamic world farther north. The tremors of the Crusades and the Mongol invasion hardly reached them, while they continued to be visited by streams of pilgrims from the east to the west of the Islamic world, many of whom, in fact, took refuge in the calm and peace of these cities from either turmoil in their place of birth, or the din of the life of the world, as we see in the case of Baha al-Din Walad, the father of Jalal al-Din Rumi who, fleeing the Mongol invasion in Khurasan, came with his young son to Mecca before settling in Anatolia; or Imam al-Ghazali, who spent years in seclusion in the holy cities. Many of those Islamic scholars, who are called Makki or Madani, hailed, in fact, from other regions of the Islamic world but settled in the two holy cities. These cities remained over the centuries as the heart of Islamic civilization whose more evident and well-known centers, as far as political, intellectual and artistic life are concerned, lay north, east and west of the sacred land of Hijaz, the birthplace of Islam. Hijaz itself continues to this day to be the religious center of the Islamic world as a result of the ever-living presence and continuing significance of Mecca and Medina.

The Ka’bah

This House of God and primordial temple dedicated to the One, which is the object of the Hajj and the focal point for the daily prayers or the qiblah of all Muslims, stands at the heart of Mecca as testimony to the nature of Islam as the pure monotheism which revived the monotheism of Abraham and ultimately the primordial message of unity revealed to Adam, at once the father of humanity and first prophet. The Ka’bah is the concrete symbol of the origin of Islam and, in Muslim eyes, of all religion. To come to the Ka’bah is to return to one’s origin. But it is also the supreme center of Islam by virtue of which all Muslims turn to it in their daily canonical prayers. Like all veritable traditional civilizations, Islam is dominated by the two realities of Origin and Center, and these two fundamental dimensions of Islamic life are present in the Ka’bah. Throughout his or her life on earth, a Muslim, whether living by one of the volcanic peaks of Java or in the desert of Mauritania, is aware of the Ka’bah as the point on earth which links him or her to the origin of himself or herself, of his or her religion, Islam, and ultimately of humanity as such. The Muslim is also aware that all points of space on earth are linked by an invisible line to a unique center which is the Ka’bah towards which one directs one’s face five times a day in prayer. The Muslim, therefore, has a relation to the Ka’bah which is at once static and dynamic, static for there is a constant link between every point of the space of the Islamic cosmos and the Ka’bah, and dynamic because it is toward the Ka’bah that one journeys during the pilgrimage. In a sense, the daily prayers (al-salah) represent that static relation and the Hajj the dynamic one. Together they confirm the overwhelming and majestic presence of the Ka’bah as at once Origin and Center in the Islamic religious universe, not because of the Ka’bah in its earthly reality but because of what it signifies as the House of God, for in reality it is God alone who is the Origin and Center of a Muslim’s life.

The Ka’bah is considered by Muslims to be a reflection here below of the celestial temple surrounding God’s Throne (al-arsh) except that by inverse analogy, here below, one can speak of surrounding the Throne while in the principal domain it is the Throne that surrounds all things as the Qur’an asserts. The archaic nature of the Ka’bah points to its primordial character. Being a cube (hence the name Ka’bah which means “cube” in Arabic) or almost a cube, it is 12 meters long, 10 meters broad and 16 meters high, possessing therefore dimensions which are in harmonic relation with each other according to the Pythagorean meaning of harmony. As a cube, the Ka’bah also symbolizes the stability and immutability that characterize Islam itself, a religion based on harmony, stability and immutability in its basic reality, hence the truth that Islam can be renewed but not reformed. It is of interest to note that the Holy of Holies in Jerusalem, in which the Ark of the Covenant was kept, was also in the form of a cube. And like the ark, the Ka’bah is considered to reflect the Presence of God. It is like a living body; hence its being dressed in the black cloth (al-kiswah), with golden Qur’anic verses. This dressing of the Sacred House of God, an old Semitic tradition not found in the Graeco-Roman world, is renewed every year and the old kiswah is cut up and distributed so as to allow the barakah of the Ka’bah to emanate among those to whom pieces of the cloth are given. From the earliest centuries of Islamic history, the kiswah was made in Egypt and carried with great care to Mecca, but now it is made near the holy city itself.

The Ka’bah is a structure with cosmic and even metacosmic significance. It lies on the axis which unites Heaven and Earth in the Islamic cosmos. It is situated at the hub of the world at the point of intersection between the axis mundi and the earth. Its properties reflect cosmic harmony. Its four corners point to the four cardinal directions which represent the four pillars (al-arkan) of the traditional cosmos. As for the Black Stone (al-hajar alaswad) at its corner, it is a meteorite, therefore from beyond the earthly ambience. Abraham (Ibrahim) and Ishmael (Ismail) are said to have brought it from the hill of Abu Qubays near Mecca where it had been preserved since coming to earth. According to the Prophet, the stone had descended from Heaven whiter than milk but turned black as the result of the sins of the children of Adam although something of its original luminosity survives. The stone also symbolizes the original covenant made, according to the Qur’an, between God and Adam and all his progeny, whereby all members of humanity accepted on that “pre-eternal moment” (al-azal), when the covenant was made, the Lordship of God.

The communal prayer around the Ka’bah is the most tangible sign of perfect submission to God’s Will as the circumambulation around it marks the return of man to his original Edenic perfection. By emptying the Ka’bah of the idols, the Prophet not only reconsecrated the Primordial Temple as the House of the One God but also taught all Muslims that in order to be truly Muslim they must empty the heart, which is the microcosmic counterpart of the Ka’bah, of all idols, of all that is other than God, making the heart worthy of receiving the Divine Presence.