Читать книгу A Rich Brew - Shachar M. Pinsker - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Odessa

Jewish Sages, Luftmenshen, Gangsters, and the Odessit in the Café

In Odessa, the destitute luftmenshen roam through cafés, trying to make a ruble or two to feed their families, but there is no money to be made, and why should anyone give work to a useless person—a luftmensh?

—Isaac Babel, “Odessa,” 1916

In 1921, after World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution, and Russian civil wars, many Jews left Odessa and migrated to other cities in Europe, America, and Palestine. Among them was Leon Feinberg, a Yiddish and Russian poet, writer, and translator. He traveled first to Tel Aviv but shortly thereafter settled in New York City. In 1954, Feinberg published a poema, a novel-in-verse titled Der farmishpeter dor (The doomed generation), that gave a voice to a generation of Jews who grew up in Odessa and ended up in America. They experienced from afar the destruction of European Jewry in the Holocaust, as well as the Stalin purges. The first part of his novel-in-verse is “Odessa,” a poetic representation of this port city at the turn of the twentieth century. Several of the poems follow Nyuma Feldman, a character from the poor neighborhood of Moldavanka, who speaks “Odessan language”—Russian tinged with Yiddish—and goes between Café Fanconi and Café Robina in the city center. In these cafés, historical figures mix freely with fictional characters crafted by celebrated Jewish writers such as Sholem Aleichem, S. Y. Abramovitsh, and Isaac Babel.1

What are these cafés, and why were they important for Feinberg and others who remembered them so vividly in New York and elsewhere after many years? The cafés played a key role in the development of modern Jewish culture in the port city of Odessa, as part of an interconnected diasporic network that developed during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Odessa’s history is unique, especially in the half century before the collapse of the Russian Empire and the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 and the subsequent Sovietization of the city. In this period, the southern city of Odessa was perceived as a center of newfound Jewish freedom from strictures of both Jewish traditional life and the Russian regime. The mythic status of Odessa and its persistent image as a “Jewish city” have been documented by historians and literary scholars alike.2 Odessa cafés have been part of both the history and the myth of the city and thus are our first example of a thirdspace, that liminal space between the real and the imaginary that can help us to understand both. Examining the confluence between the city’s cafés, its urban modernity, migration to and from the city, and multilingual Jewish literary and cultural activity enables us to see the role of Odessa in Jewish modernity in eastern Europe. Through the lens of the café, we can better understand Odessa as an anchor in the silk road of transnational modern Jewish culture in a time of far-reaching urban migration, a period of transition from traditional forms of Jewish cultural expression to modern, secular ones.

Compared with other European cities of distinction and culture, nineteenth-century Odessa was very young. Established in 1794 by the empress Catherine the Great on land conquered from the Ottoman Empire on the site of the Black Sea fortress town of Khadzhibei, Odessa received its name—after an ancient Greek settlement called Odessos—the following year. Catherine sent notices throughout Europe offering migrants land, tax exemptions, and religious freedom. In addition to a nucleus of Russian officials, Polish landlords, and Ukrainians, many non-Slavs responded to her call. Within a few decades, a new city emerged, energetic and quite different from any other in the Russian Empire. With handsome streets laid out by Italian and French architects, a harbor sending shiploads of grain to every Mediterranean port, and the leadership of a series of tolerant and economically progressive administrators, some of whom were foreign-born, Odessa’s economic foundations were established alongside its cultural ones. Thanks to its status until 1859 as a porto franco—a free port, exempt from taxes—it attracted wealthy foreign merchants and exporters. Within a few decades, it became a sizable city and soon commanded an international reputation as the preeminent Russian grain-exporting center. Thus, from its beginning until the city became known as the capital of Novorossiya, the empire’s “wild south,” Odessa was multinational, multilingual, and multiethnic. It attracted migrants of all types and creeds, with substantial numbers of Greeks, Turks, Italians, Armenians, Tatars, and Poles as well as some French, Swiss, and English.3

The city also attracted numerous Jewish migrants. Odessa was at the southern end of the Pale of Settlement, the area of the Russian Empire to which Jews were confined. This meant that Jews could settle there with few restrictions. Many Jews, both from Galicia, especially the city of Brody, and from small towns throughout the Russian Empire, made their way to the city in search of a better life. In fact, Jews were the fastest growing population in the city; they quickly adapted to the entrepreneurial business spirit of Odessa and became prominent players in internal Russian commerce to and from the city.4 In Odessa, Jews did not have to “assimilate” to a single set of customs but to an urban way of life created by different groups and ethnicities, including the Jews.5 Politically and culturally, toward the middle of the nineteenth century, Odessa became a center of Jewish life and attracted many maskilim: proponents of the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment that began to take hold in eastern European cities and towns. In the 1860s, Odessa was the empire’s center for the publication of multilingual Jewish periodicals. Rassvet, Sion, and Den appeared in Russian-language editions between 1860 and 1871, as did Ha-melits in Hebrew and Kol mevaser in Yiddish in the same period. By the late 1860s, major Jewish book publishers opened branches in Odessa, promoting, among other publications, books of the Haskalah movement. People such as the writer and editor Aleksander Zederbaum and Yitskhok Yoyel Linetski, a popular Yiddish writer, made their way to Odessa and found there ample opportunities to write and publish.6

The result was a palpable sense of Jewish freedom in the Russian Empire, although a freedom represented in highly ambivalent ways in the popular and literary imagination. People hoped to “live like God in Odessa,” as one Yiddish dictum declares, but it was also imagined as the place where “the fires of hell burn for seven miles around it,” because it was understood as a city of sin, vice, and temptations. This double image of Odessa soon became an essential component of the mythography of the city. The city was experienced both as a cosmopolitan place of enlightenment and culture and as El Dorado, a place in which one might get rich but that was also full of corruption and sin. Midway through the nineteenth century, these conflicting images of Odessa were crystallized around a number of urban cafés. Coffeehouses were not commonplace in the cities and towns of the Russian Empire. Odessa was different. People in Odessa liked calling their city “Little Paris”; the city was often compared to others in Europe and America but rarely to Moscow or other Russian cities. As Oleg Gubar and Alexander Rozenboim write in their survey of daily life in Odessa, one of the similarities between Odessa and Paris was “the presence of cafés, colorful and festive, with graceful verandas or tables simply placed under … acacias on shady, picturesque streets.”7

Odessa’s first cafés, like those in other European cities, were Turkish, Greek, and Armenian, regions that were the chief importers of coffee to the city through the Black Sea from the Ottoman Empire.8 Alexander Pushkin, the great Russian poet of the nineteenth century, lived a short period of political exile in Odessa in 1823–1824 and visited these cafés. He immortalized the city in his verse novel Eugene Onegin, in which he wrote, “like a Muslim in his paradise, I drank coffee with Oriental grounds.”9 Later, cafés in Odessa were owned also by Italians, French, Swiss, Germans, and Jews, and their food and drinks, as well as their appearance and ambience, were influenced by all the different places from which the owners came. The warm weather of Odessa encouraged many of these places to be open to the tree-lined boulevards and streets, with verandas that let people enjoy the weather and the sea air and enabled cafés to be experienced as a thirdspace, located between the inside and the outside, the private and the public.

Jewish presence in these multiethnic cafés was first recorded in the mid-nineteenth century. The 1855 Robert Sears’s guide to the Russian Empire declared that “there is perhaps no town in the world in which so many different tongues may be heard as in the streets and coffeehouses of Odessa, the motley population consisting of Russians, Tartars, Greeks, Jews, Poles, Italians, Germans, French, etc.”10 Local Jews and Jewish travelers from other parts of the Russian Empire noted the confluence of Odessa cafés and Jewish culture in the 1860s. It was an age of relative tolerance in Russia and a time of growth and maturity for Odessa’s Jewish community, which constituted a sixth of the population of the city. In a published letter from November 2, 1861, Z., a traveler from Vilna (Vilnius, Lithuania), wrote about his experience in Odessa, which he called “the capital of Jews” in the Russian Empire. “In the days after I returned from Odessa, I hastened to relate to you,” he wrote to a friend, “the impressions I had.… I won’t tell you about the beauty, the princely life, the freedom and the wealth, which is already more or less familiar to all; I will tell only that I, at least, have never seen a comparable city.… But all this is of secondary importance for Jews, as there are many beautiful cities in the empire. I want to dwell only on the situation of our coreligionists there.” As an example of what he found so attractive and exceptional in Odessa, Z. gave the city cafés: “When I stopped by Café Richelieu,” Z. observed, “I saw that almost all of the customers were Jews, who argued, read, reasoned, and played; eventually I realized that this was something in the way of a Jewish club.” What caught his attention more than anything else was that in the cafés, Jews “felt absolutely at home.”11

The attraction of Jews to Odessa’s cafés and the sense of ease and being “at home” in them, without being watched and judged, was seen as a sign of freedom and progress to some and as a threat to others. This ambivalent attitude can be seen in memoirs, letters, and newspapers, as well as in fiction written by Jewish writers. The Russian-Jewish writer, journalist, and editor Osip Rabinovich came from the small town of Kobelyaki and studied at Kharkov University before becoming a notary in Odessa. Being a notary did not stop Rabinovich from visiting and enjoying Odessa’s cafés. He also became very interested in the world of journalism and Russian literature and began to publish feuilletons and stories in Odessa’s Russian newspapers. In 1860, Rabinovich established the first Russian-Jewish periodical in Odessa, Rassvet (Dawn). In a short story published in 1865, Rabinovich described a traditional character named Reb Khaim-Shulim, a watchmaker who has troubles supporting a large family in the city of Kishinev. When he wins a lottery ticket, his appetite for business and wealth grows. Lured by stories he had heard about Odessa and the possibilities of getting rich there, Khaim-Shulim sets out not only to retrieve his lottery winnings but to move to the city on the Black Sea. “I’m going to Odessa for the money,” he declares to his good friend Reb Khatskl (Yehezkel), but Khatskl warns Khaim-Shulim’s wife, Meni-Kroyna, just as her husband enters the room, that Odessa is a dangerous place, a city of sin: “Temptations for your husband will be legion: in the café, in the theater.… It’s better, you see, that he has the Book of Psalms with him, so that in his free time he will sit and read. It’s edifying and free.”12 Khaim-Shulim does not listen to the warning of his friend, and he ends up losing all his money, returning to Kishinev with almost nothing. Thus, even if Rabinovich himself sat in cafés, for Khaim-Shulim, cafés were also a place of temptation and risk, both financial and spiritual.

We find a similar warning—that Odessa cafés were full of “sinful Jews”—in a novella by the Hebrew writer Peretz Smolenskin. Smolenskin was born in a small town in the Mogilev district, was influenced by the ideas of the Haskalah, and migrated to Odessa. He lived in Odessa from 1862 to 1867, before moving to Vienna, where we will encounter him again. Smolenskin made his debut as a writer in Ha-melits, Odessa’s Hebrew newspaper. He wrote in and about the city in his first novella, Simḥat ḥanef (The hypocrite’s joy, 1872). The novella tells the story of twenty-three-year-old David, who lived in Warsaw, participated in the Polish uprising against the Russian Empire (1863), and ran away to live anonymously in Odessa, which Smolenskin’s narrator calls Ashadot (Waterfalls). David earns a living by teaching Hebrew, as many maskilim did. The narrative unfolds in the relationship between David and his friend Shimon, another Hebrew teacher, who scolds him about his “sinful life.” When David protests these accusations, Shimon admonishes his friend, “You still ask me what sin you committed! You are hanging out with lighthearted people who indulge in gluttony, who spend their days in cafés, in places of eating and drinking, with laughter and debauchery all day long. Isn’t this a sin? To spend days and nights in folly and to waste the money you earn with the sweat of your brow; isn’t that an evil, foolishness, and a great sin?”13

Thus, the image of Odessa as “a city of sin” was bound up with cafés, as spaces of eating, drinking, and loitering that attracted Jewish men. This link between cafés and sin or folly in this period seems to be shared by both rabbis and some maskilim. As the historian Jacob Katz has noted, “social activity for its own sake, that is, the coming together of people to enjoy themselves simply by being together, was regarded as a religious and moral hazard,” especially when the sexes were mixed. But even homosocial masculine activity was viewed by some people with misgivings. It was believed to open the door to “transgressions” such as “gossip, slander, and bickering.” In addition, the requirement underpinning traditional and maskilic culture demanded of men no less than total dedication to study and thus negated any acknowledgment of the need for “leisure time.”14

Nevertheless, the attraction of these places for many people was not just the indulgence in food and drink or even the sociability that cafés facilitated. Like Rabinovich, Smolenskin became a habitué of Odessa cafés when he lived in the city, and they were central to his literary and journalistic activities. In the historical novel Sipur bli giborim (A story without heroes, 1945), the Hebrew writer A. A. Kabak portrayed Odessa’s Jewry during the 1860s.15 Some of the activities in this novel take place in the Greek café owned by Mitri Chirstopulo on Bazarnaya Street, where “penniless Hebrew maskilim, teachers of the Bible and the holy tongue, are spending their free time, together with business clerks who come to bask in the light of the maskilim, young men who ran away from their wives, and others.” In the novel, Smolenskin visits this Greek café because “he likes to be in a place in which he is the center of attention.… They welcome him there, and everybody listens to his discourse and his jokes.”16 Moreover, the character Smolenskin knew everybody in the café, since many of them were Jewish migrants like him: “Almost all visitors hail from Lithuania and Poland, fleeing the darkness and poverty of the Jewish shtetls.… In their pockets, a few coins already shake.… They still think highly of themselves because they escaped the Yeshiva, and they come from time to time to the café to play chess and enjoy the fragrance of the maskilim.”17 Soon after, however, Smolenskin concludes that—in spite of his fondness for the place—in this café, “people bury large parts of their days and nights. If they had a real passion for life, they wouldn’t sit there.”18 As these writings illuminate, the thirdspace of the café was experienced by people who enjoyed its sociability and exchange of ideas, both as a place of production and idleness, a tension that became central in Odessa, as well as in other cities.

Reading these Russian and Hebrew texts, it becomes quite clear that by the 1850s and 1860s, cafés were an important and notable part of Odessa’s urban space, and migrant Jews—maskilim and businessmen—went there to meet each other for business, to play chess, to socialize, and to further their cultural endeavors. It is also evident that these cafés, and the Jewish presence in them, could be understood in two opposite ways: one that equated the cafés with the relative freedom and civility of Odessa’s Jews, and the other with idleness and the danger of sitting around and indulging oneself.

The Blessing and Curse of Odessa Cafés

This double image of Odessa and its cafés was intensified toward the end of the nineteenth century, as Odessa became the fourth-largest city in the Russian Empire and, perhaps more importantly, “an interface between Russia and the outside world.”19 Around that time, Odessa was blessed, or cursed, with many cafés. In 1894, the newspaper Proshloe Odessy reported about 55 cafés and teahouses, 127 bakeries, and 413 restaurants in the city.20 Only a few of these establishments became well known for their food and drink, for their visitors, and for the activity that took place within their walls. German and English guidebooks for tourists in the 1880s and 1890s mention the most established and popular cafés. There was the Italian Café Zambrini, which Anton Chekhov visited; the Swiss-owned Café Fanconi, opened in 1872; and the French-owned Robina (or Robinat) and the Jewish-owned Café Libman (or Liebmann), both opened in the 1880s. Odessa also had many café-chantants (literally “singing cafés”), a kind of cabaret where singers or musicians entertained the patrons and which dotted both the center and the outlying neighborhoods of Odessa.21

“By the end of the nineteenth century,” writes the historian Steven Zipperstein, “little was left … of [Odessa’s] Italians or French influences than a smattering of splendid, popular cafés—Café Fanconi was the best well-known.”22 Many of Odessa’s Jews were attracted to these new cafés, as can be attested by Giuseppe Modrich, an Italian visitor to 1880s Odessa. Modrich wrote that he enjoyed the drinks and a wide variety of newspapers at Café Fanconi but claimed that while Odessa’s Italians are moving to America, the Jewish merchants, who “have absorbed all commercial resources,” are dominating the café and the public spaces of Odessa more generally.23 What was the nature of Odessa cafés that attracted many Jews and non-Jews in the last decades of the nineteenth century? Gubar and Rozenboim write that the famous Swiss-owned Café Fanconi “existed from 1872 … until the last owner immigrated. At first, the café was a hangout for card sharks and shady businessmen, but gradually it became a kind of club for local and visiting writers, artists, actors, and athletes.”24 The memoirs, essays, stories, poems, and plays written by Jewish writers who lived in Odessa during this time show that Fanconi and similar cafés were places of consumption and entertainment that were mixed with business, politics, literature, art, and theater.

The mix of activities in Odessa cafés reflected the diversity of Odessa’s Jews. In 1897, the 138,935 Jews constituted over a third of the city’s total population. Most of the Jews who lived in Odessa at end of the nineteenth century were migrants, from middle-class merchants to poor Jews, who were living and working as small artisans and middlemen in neighborhoods and suburbs such as the Moldavanka. The number of Jewish intellectuals, writers, and thinkers who made Odessa their home was small, but their presence made the city a major center of Jewish high-minded culture, with politics, literature, journalism, and theater. As we have seen, Odessa was an important center of Haskalah and bourgeoning Jewish press and literature since the 1860s, but toward the end of the nineteenth century, an extraordinary group of Jewish writers and intellectuals made their home in the city. The person who emerged in this period as the most important Yiddish and Hebrew writer in the Jewish world, Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh, who wrote under the name Mendele Mokher-Sforim, settled in the city in 1881, when he was invited to direct a new modern school founded by the Jewish community of Odessa. Around the same time, Odessa became the center of Jewish nationalism and proto-Zionism in the Russian Empire. Leon Pinsker, the author of Auto-Emancipation, was active in the city as the head of the Odessa Committee of Hovevy Zion (Lovers of Zion) until 1891. He was joined by the thinker Aḥad Ha‘am (Asher Ginsburg), the historian Simon Dubnow, the poet Ḥayim Naḥman Bialik, and the writers Moshe Leib Lilienblum, Elḥanan Leib Lewinsky, Yehoshu‘a Ḥ. Ravnitsky, and others. These writers, intellectuals, and political figures formed a loose circle that became known as the “Sages of Odessa.”25 They wrote in Yiddish, Hebrew, and Russian and had followers far and wide.

Some of these “Sages of Odessa” who tried to foster a highbrow sense of Jewish culture and nationalism did not know how to respond to the mixture of consumption, leisure, business, conversation, and intellectual activity that was exhibited in Odessa cafés. Somewhat ironically, this ambivalent attitude can be seen best in a Hebrew feuilleton—that hybrid literary-journalistic form that originated in Paris and became associated with the café and with Jews—titled “ ‘Ir shel ḥaiym” (City of life, 1896), in which Elḥanan Leib Lewinsky reflects on various cultural spaces in Jewish Odessa.26 In his feuilleton, Lewinsky writes that he passed with sadness a building on Langeron Street, a bustling café that only a few years earlier had been a library. After a few years of absence from Odessa, Lewinsky asks the owner of the building why, in a “city full of men of enlightenment and readers of books,” the library could not attract more readers? The proprietor answers that Odessan Jews enjoy “boisterous activity, rich food, and harsh coffee” but not books. The Jews of Odessa, Lewinsky concludes, are happy to pay good money for “the sheer pleasure of having dirty water tossed in their faces.”27

It should be clear that Lewinsky’s feuilleton and his condemnation of Odessa’s Jews’ love of cafés and “harsh coffee” does not mean that he did not frequent some of these cafés himself. However, it is indicative of a certain attitude of Odessa’s Jewish “sages” who were reluctant to frequent these cafés. Reading through their memoirs and what other people wrote about them, it becomes evident that these “sages,” especially those of the older generation, preferred to meet behind closed doors, rather than in the café. Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, there were a number of attempts to create Jewish literary and cultural clubs such as Beseda (Conversation), but they were only partially successful.28 Some of the “Sages of Odessa” met in “salons” that took place, often on Friday evenings or Saturdays, behind closed doors in the private houses of Abramovitsh, Ahad Ha’am, and Dubnow.29 These “salons”—an institution that had flourished in Europe since the eighteenth century—were an alternative to the café. Instead of the thirdspace of the café, located between the private and the public, the inside and the outside, salons were open only to a small group of people who were familiar to each other, spoke essentially the same language, and had similar concerns. As we shall see, salons of one kind or another constituted competition for the café in almost every city in which modern Jewish culture was created.

However, Odessa cafés were important for many other, mostly younger Jewish writers and intellectuals, as well as for the development of Jewish theater in the city. The modern Yiddish theater was born in Romania in the middle of the 1870s and was consolidated in Odessa in the late 1870s and 1880s, before migrating and spreading to Warsaw, London, New York, and other cities around the world. As in the case of Jewish journalism and literature, in the realm of theater, Odessa cafés were part of a cultural network of Jewish creativity in transit. Avrom Goldfaden, the leading pioneer of Yiddish theater, settled in Odessa in 1878, after some years spent in Romania, and established a theater troupe that met, rehearsed, and sometimes performed in Odessa’s cafés and taverns. The Yiddish actor Jacob (Yankl) Adler was born in 1855 to a family of migrants to Odessa and began his acting career in the city. The playwright and director Jacob Gordin also began his journalistic and literary activities in Odessa in the 1880s, before he moved to New York City and its cafés. In 1882, the Yiddish popular writer and dramatist Nokhem Meyer Shaykevitch, known as Shomer, opened a Yiddish theater in Odessa in partnership with Goldfaden. Peretz Hirshbein, who arrived in Odessa in 1908, established his own art theater troupe there. Although all these playwrights, directors, and actors migrated elsewhere—mostly to New York City—because of frequent tsarist bans on Yiddish productions, Odessa was crucial for the growth and maturity of the Yiddish theater.30

In Odessa, local café-chantants staged Yiddish plays, and both cafés and taverns influenced the creation and diffusion of music that was closely related to these theatrical performances.31 Jacob Adler wrote about his stormy youth in Odessa and how he roamed between cafés, taverns, and the Russian city theater.32 When he returned from serving as a solider in the Russian army during the 1877 war with Turkey, he started to work as a journalist at the Russian newspaper Odesski vestnik (Odessa messenger), but he spent the evenings at café-chantants and wine cellars, as well as in Café Fanconi, where he met with other actors and began his theatrical career.33 Adler soon became more involved in the theater, and his acting friends met at Café Fanconi, as well as in the Jewish-owned Akiva’s café on Rivnoya Street, where theatrical rehearsals and performances also took place.34 When Avrom Goldfaden came to Odessa the following year, there was much excitement at Café Fanconi, where “everybody already gathered, all talking about Goldfaden and the sensation his arrival made.”35 Eventually, Adler acted with Goldfaden’s troupe in Odessa and other cities in the Russian Empire, before he migrated to London and to New York City.

The role of Odessa cafés as part of a growing network of Jewish culture can also be seen in the activities of Jacob Gordin, the most important Yiddish playwright of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Gordin was born in Mirgorod, a small town in Ukraine, and traveled far and wide in the Russian Empire. He lived in Odessa and, like Adler, published essays in Russian, in the local liberal newspaper Odesski vestnik.36 In the 1880s, Gordin frequented Odessa cafés and knew them very well. Although he started writing Yiddish plays only after his migration to New York City, many of his plays depict Odessa and are infused with Odessa’s society. A case in point is Gordin play’s Saffo (Sappho), produced in New York in 1900.37 The entire play takes place in Odessa and is based on Gordin’s familiarity with the city and its social and cultural life.

The main figure of the play is Sofia Fingerhut—dubbed “The Jewish Sappho”—a figure of a “New (Jewish) Woman,” who works in an office to support herself. At the beginning of the play, Sofia is about to get married to Boris, a modern Jewish photographer. Matias Fingerhut, the father of the bride-to-be, is torn between his happiness about the marriage and his fear of the new values that his daughter and Boris share. Mr. Fingerhut declares to his daughter and wife that he is “going to treat himself to tea in the terrace of Café Paris—perhaps the French-owned Café Robina—so everybody will know what sort of man [he] is.”38 In this case, Matias, a migrant to Odessa and a merchant, is clearly torn between his notion of masculinity, Jewishness, and middle-class respectability and his daughter’s newfound independence. Soon after, Sofia finds out that Boris really loves her sister, Lisa, and refuses to marry her, in spite of the fact that she has a baby with him. In act 2 of the play, which takes place a few years later, Sofia continues to live and work as a single woman. Boris and his friend Samuel Tseiner discuss match-making in Café Fanconi, and Mr. Fingerhut also visits the café, where he receives much information about the relationships between his daughters and the men in their lives. He finds out that a young Jewish pianist, with the nickname Apolon, fell in love with Sofia/Sappho, but she resisted him. The play ends with Sofia moving out of Odessa with her little daughter.

Although Gordin wrote the play for an American Jewish audience in New York, where it was very successful, it was clear to viewers that modern Russian Jewish figures (Boris, Sofia, and Apolon) were likely to be found in Odessa. These young Jews, as well as their merchant father, could flaunt their modernity in Cafés Fanconi and Paris. But Gordin’s play also highlighted an important gender element of Odessa’s cafés. Sofia, the modern Jewish woman, only hears about what is going on in the cafés but never participates in their social life. Throughout the nineteenth century, Odessa cafés were developed as homosocial, masculine spaces, where “respectable” women were not to be seen. Thus, Sofia’s relative independence as a working, single woman could not be sustained in Odessa’s cafés.

Gordin’s play is a good example of the importance of Odessa cafés in modern Jewish life, but it also highlights the conflicts and tensions around gender and around the changing contours of what it meant to be “Jewish” in the modern urban environment of Odessa. Indeed, during the final decades of the nineteenth century, Odessa cafés were very popular, but they were also spaces of various conflicts and tensions, not just between traditional and more modern Jews but also between men and women, businesspeople and intellectuals, Jews and gentiles. The vigorous Jewish presence in these cafés attracted much attention, for better or worse. After the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, when there were waves of anti-Jewish violence in the Russian Empire (even in Odessa), the reaction to the Jewish presence in cafés was sometimes marked with anti-Semitism, real or perceived, as well.39 On August 10, 1887, Ha-melits reported about a story published in Novorossiysk telegraph, a regional Odessa newspaper that was known as instigating Judeophobia:

The Jewish community of Odessa decreed a boycott on the tavern of Mr. Fanconi and made it forbidden to all Jews to step inside the house, because he printed in the journal a letter and cursed the Jews who made it a communal space. On both sides of the coffeehouse Jews stood up and announced this boycott; they took note of anyone who did not obey them and entered the café. Mr. Fanconi is very happy with this boycott because now the huge crowd of Jews, who used to do business there, stopped visiting; instead many Christians continued to frequent it, to drink and eat there to their heart’s content.40

Less than two weeks after the report, in the same Hebrew newspaper, Ravnitsky, who used the pseudonym Bar-Katsin, wrote a story in order to better explain what happened and to further report on the latest outcome of this affair in Café Fanconi. Ravnitsky wrote,

For the sake of the readers who are far from Odessa, I would like to explain the meaning of this event, which became a topic of conversation for everybody in our city. Fanconi is not a tavern but the largest café and pastry shop in the city of Odessa. This is the meeting place of many not-so-small merchants, the elite of Odessa who do not care much about money. The establishment, which stands proudly in the center of the business district, became a meeting place of every respectable merchant. And when one merchant looks for another, he knows that he would find him in Fanconi and converse with him over a cup of coffee and sweet pastries. It is easily noticeable that almost all the habitués of the café are our Jewish brothers.… In the checkbook of every Jew in our town … you would find a nice sum that was payable to Fanconi.… With the price one pays for a cup of coffee and light delicacies, a poor man with a wife and five children can live quite comfortably.41

In short, Ravnitsky contended, since the opening of the café, the relationship between the middle-class Jews of Odessa and Café Fanconi was beneficial to all. What instigated the Fanconi affair was a young and poor maskil, who used to frequent Fanconi without having enough money to pay. Somehow he always got by, with one person or another paying for him, until the waiters of the café had enough and decided to throw water on him in order to scare him off. This act created a strong backlash, with many of the Jewish habitués of the café scolding the waiters.

According to Ravnitsky, in response to all this, Mr. Fanconi himself wrote a letter to Novorossiysk telegraph, seeking to defend his workers and blame the Jews for “turning his café into a tavern, making noise, and creating mayhem.” The habitués decided to do the unthinkable, namely, to avoid Fanconi, and the café became almost completely empty, to the chagrin of Mr. Fanconi. Subsequently, he decided to publish a large announcement in the liberal newspaper Odesskie novosti (Odessa news) that, according to Ravnitsky, said the following: “The good relationship between Café Fanconi and the maskilim of our city over many years forces me to explain in print … that all the rumors about Jews refusing to visit the café are completely wrong, because most Jews, apart from a small minority, continue to frequent the coffeehouse. I ask all those who were insulted by the ugly act of the waiters or by misunderstanding our announcement in Novorossiysk telegraph to understand that I never meant to offend the Jewish people.”42

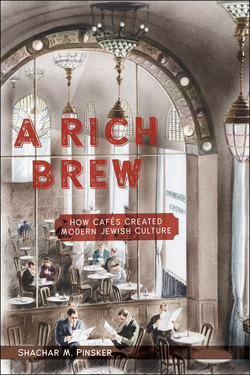

Figure 1.1. Postcard of Café Fanconi, Odessa

Mr. Fanconi noted that nobody could accuse him of anti-Semitism and that he warmly welcomed everybody (“and their deep pockets,” adds Ravnitsky) with open arms. Ravnitsky’s report ends with the conclusion that the outcome of the affair was that most, if not all, of the Jewish habitués returned to their beloved Fanconi, but these events caused “our brothers to raise their self-evaluation as Jews.”43 Thus, we can see that Odessa’s prominent cafés were spaces of tensions and contested meanings. The highly visible attraction of Jews to Café Fanconi was so prominent that it made it appear as a modern “Jewish space.” Mr. Fanconi and his waiters might not have liked the marking of the café as Jewish, but they depended on it in order to continue to flourish. Moreover, we can see the economic tension between middle-class merchants and maskilim, as well as between Jews and non-Jews and even among the owner, the waiters, and the habitués.44

These tensions and the fact that Jewish modernity in Odessa was inextricably bound to its cafés became evident to Ravnitsky’s friend, the young Sholem Aleichem (Sholem Rabinovich), who was soon to become one of the most beloved and influential Yiddish writers in the world. Sholem Aleichem came to Odessa from Kiev in 1891, after he lost all his father-in-law’s wealth in the stock exchange. He lived in Odessa for a number of years, trying to make a living by publishing in Russian, Hebrew, and Yiddish. These years in Odessa were difficult financially for Sholem Aleichem but also very memorable and productive. Unlike some of the “Sages of Odessa” but like Adler, Goldfaden, Gordin, Ravnitsky, and Rabinovich, Sholem Aleichem enjoyed visiting Odessa cafés, eating, drinking, observing, and participating in the activity that took place there. In London: A Novel of the Small Bourse (1892),45 which is the first part of what evolved to become the epistolary novel The Letters of Menakhem-Mendl and Sheyne-Sheyndl, Sholem Aleichem makes masterful comic use of the space of Café Fanconi. More than any text written before it, Sholem Aleichem’s novel situates Odessa’s cafés on the map of modern Jewish literary imagination.

In the novel, the protagonist, Menakhem-Mendl, who arrives in Odessa from his tiny fictional shtetl Kasrilevka, is bewitched by the stock market and the currency-exchange market of Odessa, where he believes he has made a large amount of money quickly and without much effort. Menakhem-Mendl is equally allured by Café Fanconi, the location of the elusive “small bourse” in the novel’s subtitle, where business is done over a cup of coffee or tea. As he writes to his provincial wife, Sheyne-Sheyndl, whom he left behind in the shtetl, “If only you understood, my dearest, how business is done on a man’s word alone, you would know all there is to know about Odessa. A nod is as good as a signature. I walk down Greek Street, drop into a café, sit at a table, order tea or coffee, and wait for the brokers to come by. There’s no need for a contract or written agreement. Each broker carries a pad in which he writes, say, that I’ve bought two ‘shorts.’ I hand over the cash and that’s it—it’s a pleasure how easy it is!”46

After a few days, Menakhem-Mendl boasts that he is so successful in Odessa that all the dealers already know him in Café Fanconi:

By now they know me in every brokerage. I take my seat in Fanconi with all the dealers, pull up a chair at a marble table, and ask for a dish of iced cream. That’s our Odessa custom: you sit yourself down and a waiter in a frock coat asks you to ask for iced cream. Well, you can’t be a piker—and when you’re finished, you’re asked to ask for more. If you don’t, you’re out a table and in the street. That’s no place for dealing, especially when there’s an officer on the corner looking for loiterers. Not that our Jews don’t hang out there anyway. They tease him with their wisecracks and scatter to see what he’ll do. Just let him nab one! He latches on to him like a gemstone and it’s off to the cooler with one more Jew.47

It is hard to mistake the target of Sholem Aleichem’s biting humor. The provincial Menakhem-Mendl, the quintessential luftmensh (man of the air), would soon lose all his money in the Odessa speculative market, as Sholem Aleichem himself did in Kiev and as the character of Khaim-Shulim did in Osip Rabinovich’s novel. But Menakhem-Mendl’s experience also captures something essential about the Odessa café as a metonym for the contradictions of urban Jewish modernity.48 Sure, the café gives anyone, even Menakhem, access to a marble-top table and, along with it, to conversations about politics and culture and even to the business that presumably takes place by a mere nod. Moreover, all of this can be done while a waiter in a frock coat will serve you coffee and the best ice cream in the city. However, if you lack the money to order a few servings, you are out in the street, in danger of being picked up by a police officer ready to roust any Jew who might interfere with the life and the business of the café. Sholem Aleichem builds on Osip Rabinovich’s Khaim-Shulim and on Ravnitsky’s maskil in “the Fanconi affair,” but his comic genius goes deeper in penetrating into Odessa café life.

We can see through Menakhem-Mendl’s letters to his wife that the modern business that takes place in the thirdspace of the café is different from the “old” and more tangible business. It is very much tied to smart conversations about politics and news, which Menakhem-Mendl can only partially follow. He tries to explain to his wife that her “doubts about the volatility of the market reveal a weak grasp of politics.” Menakhem-Mendl gets his “grasp of politics” in Café Fanconi by speaking to a habitué named Gambetta, “who talks politics day and night. He has a thousand proofs that war is coming. In fact, he can already hear the cannon booming. Not here, he says, but in France.”49 Thus, one can presumably sit in an Odessa café, where journalists and readers gather, read newspapers from all over the world, follow the news about the war in Paris and London, and speculate on currencies and stocks that are part of the new modes of capitalist economy. This economy is like the ephemeral “market” in the café that people like Menakhem-Mendl cannot really fathom, even if he desperately tries to.

Menakhem-Mendl’s wife, Sheyne-Sheyndl, is as essential to the epistolary novel and to understanding Jewish café culture in Odessa as the male antihero is. In spite of the fact that she never leaves the shtetl of Kasrilevke, she is able to mount a critique of Café Fanconi and the conversations and business that go on there. About Gambetta, the source of knowledge about politics and market manipulation, she writes to her husband, “And as for your Gambetta (forgive me for saying so, but he’s stark, raving mad), I’d like to know what business of his or his grandmother’s it is. You can tell him to his face that I said so. What kind of wars is he dragging you into?”50 Sheyne-Sheyndl is also highly suspicious about the fact that her husband spends so much of his time at Café Fanconi, instead of doing some more traditional business or work. She also suspects his fidelity when she writes, presumably without even understanding what a café is or what its name is, “And by the way, Mendl, who is this Franconi you’re spending all your time with? Is it a he or a she?”51

Although the café habitués used to be all men, just around the time Sholem Aleichem wrote his comic novel, modern women began to access the café, which raised the suspicions of traditional wives like Sheyne-Sheyndl. It is also clear that she is correct about the demise of her husband’s business activities. Soon enough, Menakhem-Mendl starts to lose everything he gains and more. At this point, he confesses, “I tell you, my dearest wife, I’ve had my fill of Odessa and its market and its Fanconi and its petty thieves!”52 In Sholem Aleichem’s novel, Café Fanconi can indeed be a dangerous place if you do not know how to navigate your way in this thirdspace of urban modernity. Odessa cafés were clearly both a blessing and a curse to many Jews who migrated to the city and made their home there. While they were crucial to the development of Jewish business, politics, theater, music, press, and literature, they also exposed strong anti-Semitic sentiments, the challenges of modernity, and changing economic and class structures. The café was becoming a site of tense negotiation around consumption and politics, gender, and the widening economic gaps that were part and parcel of Odessa’s Jewish urban modernity.

Revolution, Pogroms, and Politics in the “City of Life”

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Odessa’s status as a center of modern Jewish literature and culture unparalleled in the Russian Empire was firmly established, as was its role as an anchor in a network of Jewish culture. This did not stop its reputation for being full of wealth and full of sin. The tensions that were visible after 1881 in Odessa cafés and elsewhere only intensified in these years, when the Russian Empire entered a deep recession. Odessa’s economy suffered a setback due to the decrease in demand for manufactured goods, a drop in the supply of grain available for export, and the drying up of credit. There were flaws in Odessa’s economic infrastructure, and conditions continued to deteriorate, especially following the outbreak of war between Russia and Japan in 1904. All these developments fused together with the political and economic unrest that swept the Russian Empire before the failed 1905 revolution against the tsarist regime; that unrest was especially high in Odessa, in spite of its relative distance from imperial centers and its reputation as a multiethnic, cosmopolitan “city of life.”53

One of the defining moments of that aborted revolution took place in Odessa: the rebellion that erupted on the Russian battleship Potemkin on June 14, 1905, immortalized by Sergei Eisenstein’s film The Battleship Potemkin (1925). A few months after these dramatic events, Tsar Nicholas II issued the October Manifesto, promising political reforms. A large pogrom, a wave of anti-Jewish violence, erupted in Odessa on October 18–22, 1905, in which at least four hundred Jews and one hundred non-Jews were killed and approximately three hundred people, mostly Jews, were injured. Around 1905, a new generation of Russian Jews—some born in Odessa, others who had migrated to the city—came of age and found their place within the city’s cultural life. The October pogrom and several others that followed it thoroughly shaped members of this new generation but did not dim their engagement with the city. Most of them felt thoroughly at home in Russian language, literature, and culture, and they made good literary use of the unique Russian dialect of Odessa, which was tinged with Yiddish and Hebrew and with influences of many other languages spoken in Odessa. Odessa continued to attract young people from the Pale of Settlement who wanted to bask in the light of the “Sages of Odessa,” but many of Odessa’s new writers and cultural figures, as well as its merchants and lower-class workers, were born in the city and proudly considered themselves to be real Odessits. Odessa cafés continued to play an important role in the city and in Jewish culture in the tumultuous and occasionally violent years around the revolution. Much of the writing in and about the café reflected on the changes that took place in Odessa and the tensions that abounded around the aborted revolution and the pogroms.54

The Jewish-Russian writer and journalist Vladimir Jabotinsky was born to an acculturated middle-class family in Odessa in the year 1880. The young Jabotinsky, who later became the leader of the Zionist Revisionist party in Palestine became the chief cultural correspondent for the prestigious Russian daily Odesskie novosti, writing many witty feuilletons. Jabotinsky used to sit in Odessa’s famous cafés, writing, observing, and gathering information about cultural events in the city, as well as in the simple Greek cafés near the port, which he especially liked. Years later, he wrote about the city in his semiautobiographical novel Pyatero (The Five, 1936).55 In the novel, Jabotinsky chronicles the lives of five children in the Milgrom family and their different orientations, choices, and fates. Many of the events in the novel take place in the center of Odessa, where “one could see the trading terraces” of the two most famous institutions, Café Fanconi and Café Robina, which were “noisy as the sea at a massif, filled to overflowing with seated customers, surrounded by those waiting to get in.”56

The narrator’s view of these cafés as sites of “trading” captures well the mixture of business and pleasure, literature and culture, sociability and commodity, in the period before 1905. The changes that occurred in Odessa after the turbulent events of 1905 are also experienced and depicted through the cafés, which according to Jabotinsky suddenly emptied. In fact, for Jabotinsky and his narrator, after 1905, Odessa would never be the same city, and the years of the fin-de-siècle constituted the golden age of Odessa, its cafés, and its other public spaces. Jabotinsky describes in the novel a literary club that met in a building at the center of Odessa in 1903 as an ideal location for cultural mixture: “I think that most interesting of all was the peaceful brotherhood of peoples amongst us at the time. All the eight or ten tribes of old Odessa met in this club, and really it entered no one’s head, even silently to oneself, to notice who was who.”57

Something of the way Jabotinsky experienced the cross-cultural pollination of the years before 1905 can be seen in the memoir of his friend Israel Trivus, one of Odessa’s Zionists. Trivus wrote about his encounters with Jabotinsky in 1904. According to Trivus, Jabotinsky said that in the Greek Café Ambarzaki, “there is an aroma of Asia, … but it creates an ambience that takes you up to the sky, where there is no limit to your thought and imagination.” Playing on the Greek name of the café, Jabotinsky claimed that when he got to know this “lofty institution” well enough, he finally understood “the ancient Olympus, where one could enjoy ambrosia and nectar,” and that “God’s nectar is really a fragrant cup of Turkish-style coffee, and ambrosia is rahat lokum [Turkish delight] and halva.”58 However, it was not just the divine food and drink that Jabotinsky was attracted to but the conversation with the Greek owner of the café. He was enthralled with the visitors’ talk, which, according to Trivus, revolved around Greek and Jewish national movements and the emerging Zionist movement, as well as around the glories of Odessa, Pushkin’s poems (which Jabotinsky recited from memory), the city, and its cafés.59

The cafés that Jabotinsky’s narrator wrote about embody the way he understood the spirit of Odessa before 1905, but things changed drastically after that in Jabotinsky’s novel and in reality. During the year 1905, with the aborted revolution and with the pogroms that followed in the next months, the activity in Odessa’s cafés was very different. Some cafés were even in the line of fire. The most famous of them was Café Libman, the Jewish-owned establishment in the center of Odessa, which was located within the well-known Passage building.60 Café Libman was bombed by a group of socialist-anarchists in December 1905. Their mission was to spread propaganda in the factories and organize revolutionary labor unions as vehicles of class warfare. The bombing was a part of their effort to create “economic terror.” Apparently, the Jewish owner of Café Libman was blackmailed by the anarchists. They did the same thing to other shopkeepers and café owners, whom they described as “bourgeois bloodsuckers.” When Mr. Libman refused to pay them protection money, the café was bombed, which caused much damage to the café, as well as injuries.61

These economic and political tensions were a crucial part of Odessa’s modern Jewish culture. One of the most important aspects of the “economic terror” in this period was that not only were the owner of the café and many of the visitors Jewish, but so too were many of members of the anarchist group. As the historian Anke Hilbrenner claims, Café Libman might have been chosen as a target precisely because the owner of the café was known to the anarchist terrorists. Moreover, Café Libman was not really the café of the “bourgeois bloodsuckers,” as the anarchist sources claimed, but a place where students, liberals, and intellectuals would go. Since many of the guests were Jewish, some of the people injured in the bombing were Jews, including families with children. One of the Odessa anarchists, Daniel Novomirsky, criticized the bombers precisely for bombing a café where the “local intelligentsia” would sit and drink tea and coffee.62

If the bombing of Café Libman, which was soon renovated and continued to flourish for another decade, was a sign of the occasionally violent class warfare in Odessa, the pogrom in Odessa was a painful reminder that the city was never immune to anti-Semitism. A number of writers described in their fiction the devastation of the anti-Jewish violence in texts that were centered in cafés and similar institutions. The most famous is Alexander Kuprin’s short story “Gambrinus” (1907).63 Kuprin was not Jewish but a major Russian writer who presented a nuanced portrait of the Odessan Jews in his writing. “Gambrinus” is the name of a real establishment in the center of Odessa. It was not a café like Fanconi, Robina, or Libman but an underground establishment, a mix of tavern and café-chantant, in which music was played every night. In the story, the most beloved musician in Gambrinus was Sashka, an Odessan Jewish fiddler who was steeped in the tradition of Jewish (klezmer) music that developed in Odessa. Sailors and workers would flock to see and hear Sashka because he mesmerized audiences with his improvised response to the most varied requests, from Russian folk melody to Viennese waltz to an African chant.

In this period, Jewish musicians, especially fiddlers, began to dominate. The fictional Sashka was based on a real figure, Sender Pevzner, familiar in Odessa for his violin playing. In Kuprin’s story, Sashka volunteers to fight in the tsar’s army during the 1904 war with Japan. After his return, the pogrom in Odessa erupted, and the very same people who enjoyed Sashka’s playing in Gambrinus were suddenly incited against Jews. One day when Sashka was walking in the streets of Odessa, a stonemason wanted to attack him with his chisel. When someone grabbed the hand and said, “Stop, you devil,—why it’s Sashka!”64 the assailant stared and stopped—and smashed the brain of the little dog that was always found in Gambrinus instead. But then Sashka disappeared, nobody knew where; when he returned to Gambrinus, his arm was broken, and the visitors of Gambrinus realized he could not play his fiddle. The story ends with the triumph of art over the force of anti-Semitism and violence, as Sashka takes up a small harmonica and begins to play one of his beloved tunes.65

Thus, the violence of the revolution and the pogroms entered Odessa cafés and became enmeshed in modern Jewish culture in the city. These elements play also a major role in Ya’akov Rabinovitz’s Hebrew novel Neve kayits (A summer retreat, 1934).66 The plot of the novel takes place in the summer of 1905 between a fontan—an Odessa seaside resort—and the city, with its cafés, restaurants, and theaters. It revolves around the life of young Jewish men. All of them are acculturated to Russian culture; some are from bourgeois families, and others belong to revolutionary movements. The tensions between Jews and non-Jews and the threat of anti-Semitism and violence gradually enter their bohemian life. These tensions can be seen, for example, when one of these characters, the highly sensitive Yitzḥak Yonovitz, walks on an Odessa boulevard and sees his friend Volka Wolfman—a man with a “Russian look,” who is active in revolutionary circles—sitting in a café eating watermelon together with a security guard and a few other non-Jews. Yitzḥak stops himself from greeting his friend and joining him at the café because he thinks that it is better not to reveal his Jewishness.67

The end of the novel comes after several acts of violence against Jews and revolutionaries. At this point, the plot moves from the seaside and the boulevards of central Odessa to the suburb of Moldavanka, which had become infamous for its destitute Jewish residents and for poverty and crime. The narrator describes a humble café, with simple food, that is owned by a Jewish family and frequented by Jews. Yitzḥak and his friends and a Jewish merchant who normally would not be seen around go to this Jewish café and talk about the violent events in Odessa. One of the visitors, an owner of a small hotel, complains that “there is no rest, they destroy the city, the commerce, and everything. And we are Jews.”68 It is unclear if Yitzḥak refers to the revolutionary activists or to the perpetrators of the violent pogrom. But the implication in Rabinovitz’s novel is clear: during these turbulent times, Jews of all backgrounds feel more at home and more able to talk about their situation in humble cafés in the Moldavanka or in the Jewish and Zionist self-defense circles than in places such as Cafés Fanconi, Robina, or Libman.

After the devastation of the revolution and the pogroms, Odessa seemed to calm down and return to normal. However, social, religious, ethnic, and especially economic tensions were always simmering just beneath the surface. Odessa became full of anarchist movements, Jewish self-defense groups, and ordinary criminal gangs, with gangster leaders such as the Jewish Mishka Yaponchik. Before the Russian-Jewish writer Isaac Babel wrote his famous “Odessa Stories” in the 1920s and captured these tensions and the contraband activity that took place in the city after 1905, Sholem Aleichem described them in a Yiddish short story, “Dray lukhes” (Three calendars, 1913). The story is a monologue of an unnamed Odessan Jew, a married man with children, who makes a living by selling contraband, namely, smutty “interesting postcards from Paris.”69 The historical context for this monologue, and for the narrator’s unusual occupation, is the tenure of Ivan Nikolaevich Tolmachev as a governor of Odessa between 1907 and 1911, which brought some order to the streets of Odessa but was also heavily repressive. Many Jews considered Tolmachev to be not only counterrevolutionary but also anti-Jewish.

The narrator explains that the fact that he sells smutty postcards has something to do with his interaction with Tolmachev before 1905, when “a Jew could roam around as free as a bird” and sell his Jewish books near Café Fanconi, because “you could always run into Jews there, for that was the area where speculators, agents, and various other Jews hung around waiting for a miracle.” The narrator tries to sell a few calendars that were left in his stock a few weeks after the High Holidays. Looking at the habitués of Café Fanconi, he realizes that he knows “every single one of them even blindfolded.” Then he sees a decorated army general sitting by the front table in the open veranda of the café, accompanied by an assistant, whom he is in the process of sending to his wife at home with an important message. When the general catches a glimpse of the narrator standing in front of him, the narrator asks him in his broken Russian, “Your Excellency, how would you like to buy a calendar?” The general actually buys one from him, apparently to get rid of him.70

The narrator, desperate to sell the last calendars in his stock, remembers Tolmachev’s home address and goes there, selling another calendar to his young, beautiful wife. After this success, the narrator hurries back to Café Fanconi in an attempt to get rid of the very last calendar. He sees what appears to him to be another army general, but then he realizes that he is “just one of the waiters from Café Fanconi, running with a napkin tucked under his arm and wiping the sweat from his face.” When the waiter tells the narrator that the general asks to see him again, he is sure that “his general” likes the Jewish calendar so much that he has sent the waiter to fetch him another one, and he begins to negotiate the price. The story then cuts off abruptly, but we know the end was not good: “We don’t dare show our faces on the streets selling a Yiddish or Hebrew book or a paper. We have to hide it inside our coats like contraband or stolen goods.… So I have to have a sideline business—‘interesting postcards from Paris.’ ”71 Sholem Aleichem’s satire is directed in this story toward the narrator, a simple Jew, a family man, who tries and fails to adjust to the new times. But the bitingly ironic story is multidirectional. It demonstrates that in the years before World War I, Odessa cafés were the sites of political and economic change and also of tense negotiations. The negotiations in the thirdspace of the café occurred between Jews and gentiles, unwanted migrants and the authorities, the poor and the rich. All of these elements represented different versions of Odessa’s cultural identity and of what it meant to be an Odessit in the café.

Middle-Class Respectability, Gender, and Jewish Gangsters

In Sholem Aleichem’s “Three Calendars,” the poor Jewish man who used to sell Jewish calendars around Café Fanconi turns into a dealer in smutty postcards from Paris; other Jews become swindlers and gangsters in and around Odessa cafés. According to Jarrod Tanny, the years before World War I were critical to the development of the Odessa mythography, as writers, journalists, and other myth makers depicted “the thieves and other deviant characters who shaped and were shaped by Odessa.”72 A good example of this mythography is the work of the Jewish-Russian writer Semyon Yushkevich and especially his three-volume novel Leon Drei (1908–1919). The main protagonist, Leon—whose last name derives from the Yiddish word dreyen: to spin or to swindle—likes to create an image of himself as a financially and romantically successful person. He is engaged to Bertha, and both of them think about opening a store. Leon is happy to deposit the dowry he received from his future father-in-law. As he leaves the bank, Leon contemplates, “It’s time to have a snack! I want to drink a shot of vodka and eat a sandwich with sardines.”73 But then, Leon changes his mind: “He felt that instead of vodka, he would happily drink a good, fragrant cup of coffee with cream, and he directed his steps toward the French Dupont Café. He chose Dupont because this café was considered to be the best in town. Many distinguished citizens gathered here: dealers, bankers, merchants, frivolous music stars, high-society ladies, cardsharpers, and other no less respected and respectable people. Leon had his day schedule planned when he entered the rotunda, where the habitués of the café sat at tiny marble tables.”74

This is a good example of how Odessa and its cafés became tied, together with the fictional Leon Drei, with swindlers who make appearances in cafés. In the popular and literary imagination, Odessa in the 1910s became a “city of rogues and gangsters,” and this depiction was linked to Jewishness and to Jewish culture and to café culture, implicitly or explicitly. As in Prohibition-era Chicago, crime was central to the city’s identity. William E. Curtis, a traveler from North America, wrote that Odessa was “one of the most immoral communities in Europe,” where the locals are “given to gambling and dissipation of all kinds.” He noted the many cafés in Odessa, where “all night the air is filled with music and laughter, and pleasure-seekers turn night into day,” and he wondered when the people in the cafés “attend to their business.”75

The American journalist Sydney Adamson, in his profile of Odessa in 1912, also perceived the cafés as an essential part of the cultural identity of the city and its citizens.76 He wrote that “everybody in Odessa goes, at some time or other, to Robina[’s], or to Fanconi[’s] across the way.” He noted especially the presence of “ladies,” which was a growing phenomenon in the cafés, and of men of “commercial and official monde.” His impression of Café Fanconi’s “comfortable atmosphere of tea and cakes” reminded him of “Parisian shops in the Place Vendome or Rue de la Paix” and “might even belong to Fifth Avenue” in New York City.77 Apparently, both gangsters and respectability could exist in Odessa cafés side by side in an elusive and potent harmony.

These impressions of Odessa’s famous cafés and their habitués and visitors raise the issue of what the historian Roshanna Sylvester has called “respectability,” which was of utmost importance to many journalists and others who attempted to safeguard Odessa’s reputation and its public space.78 Moreover, the comparisons of Odessa and its cafés to other cities, made by visitors and locals alike, seem to be part of an anxiety about Odessa’s identity and in particular the notion that Odessa was a pale imitation of other, more “authentic” and much larger urban centers. This anxiety can also be seen in a 1913 guide to the city, in which Grigory Moskvich, who composed a series of guides to cities in the Russian Empire, wrote that the dream of the “essential Odessit” was to “transform himself into an impeccable British gentleman or blue-blooded Viennese aristocrat.” Then, “immaculately dressed, with an expensive cigar in his teeth,” the Odessit was ready to meet his public. Whether “getting into a carriage or sitting down in one of the better cafés,” the Odessit was “out to impress by his appearance, aware of his own worth, looking down on everyone and everything below.”79

Not only Russian and American travelers to Odessa were worried about the issue of middle-class respectability and paid much attention to life in its urban cafés. Sylvester has analyzed how Odessa’s Russian newspapers, especially the progressive Odesski listok and the more lurid publication Odesskaia pochta, covered the city and its cafés in their feuilletons and stories. Many of the journalists who wrote in these papers were Jewish, and the dominant culture of the city was marked as Jewish because lower-middle-class Jews were “more responsible than any others for giving texture to the Odessan form of modernity.”80 One of the most prolific and popular journalists who covered Odessa’s urban scene was the Jewish Iakov Osipovich Sirkis, who used the pseudonym Faust. Faust wrote in Odesskaia pochta many feuilletons about the city’s social and cultural landscape and claimed that when Odessa infants start to talk, “the first word they pronounce is [Café] Robina! Especially clever ones utter the phrase, Robina and Fanconi!” he proclaimed. The father rejoices, Faust continued, “As I live and breathe, the baby will be a big merchant!”81

Another feuilletonist in the same paper, with the name Satana (Satan), expressed similar feelings about the importance of the city’s two most prominent cafés: “Every Odessan, regardless of social position, considers it necessary to go to the Robina or Fanconi at least once in their lives,” Satana declared, but especially to the Robina. “To live in Odessa and not go to the Robina is like being in Rome and not seeing the pope.” In a feuilleton penned by Leri, one of Odesski listok’s journalists, in June 1913, the journalist wrote about Odessa’s popular cafés: “It is always the way in Odessa. First, the tasteless smoke-filled mansions of Robina, Libman.… a cup of coffee, and business conversation; then, an assault and battery, breach of the public peace; then, the bleak chamber of the justice of the peace. And the next day small synopses printed in the newspapers. Such are our ways, a kind of Odessan fun-house mirror.”82

Café Robina, mentioned in so many of these feuilletons, was founded in the 1890s, across the way from Café Fanconi on Deribasovskaya Street. The two cafés were competitors but also formed a kind of symbiotic relationship, as visitors used to move from one to the other. In the early 1910s, the local newspapers reported that Café Robina became Odessa’s most fashionable haunt, a main hub of middle-class social life. Among its denizens were some of the city’s most high-profile personalities: politicians, financiers, high-ranking officers, distinguished professionals, and “stars” from the world of entertainment, as well as many journalists and writers, who no doubt made the place more famous and desirable by writing about it. Part of the reason for Café Robina’s popularity was that it served so many purposes. Businessmen and politicians came there to work, negotiating deals or conducting meetings over coffee and sweets. Others came in search of work, hoping to strike up profitable acquaintances with successful entrepreneurs, exporters, merchants, or brokers. Many others, including women, came simply to relax, enjoy the company of friends, and catch up on the news of the day.

Odessa’s middle-class women were a growing public presence on the streets of the city. They were known to “take tea” in the “ladies’ sections”—it is unclear whether these sections were completely segregated or were created more ad hoc with certain tables of the café—that presumably existed in Café Fanconi, Café Robina, and other Odessa cafés. But there was much male anxiety about the growing phenomenon of the modern, independent women sitting in cafés. An Odesski listok piece titled “Ladies Chatter” tried to give readers some insight into what these women do in the café and the content of their half-Russian, half-French conversation: “Yesterday evening we intended to go to the Café Robina.… We got in the carriage and arrived—where do you think—at Ditman’s! … Imaginez vous! … I, of course, was astounded.”83 It was not only the presence of “unrefined” women in the cafés that worried the journalists and writers. Journalists also reported on the fact that Café Robina charged astronomical prices for their food and drink in spite of not-so-perfect sanitary conditions. Odessa’s journalists mounted a critique of the visitors, especially young people who were drawn to the Robina’s “fairy-tale atmosphere.” The columnist Faust declared that when “a bashful youth” wanted to “fix a meeting with a girl,” he would exclaim, “To Robina!” When a “proper” lady wanted to talk with a “proper” gentleman, she would whisper, “To Robina!”84

Figure 1.2. Postcard of Café Robina, early twentieth century

The journalists in Odessa’s local press began to speak about a type: the Robinist, the habitué of Café Robina. The most typical Robinist was presumably a young man, son of the middle class, well bred and well educated, who should have been the pride of polite society but was its nemesis. According to journalists, Robinisti were always immaculately dressed, giving every appearance of gentility, but in fact were devious, cynical men. The journalist Satana pointedly unmasked the young men as social frauds: “Look at them. They have chic visiting cards, collars brilliant and elegant, ties that are something delicious. All signs stamp them as higher gentlemen. But if you probe one, you will find a rogue, a thorough rogue.”85

Eliezer Steinman, a modernist Hebrew writer who lived in Odessa during much of the 1910s, before he moved to Warsaw’s and Tel Aviv’s cafés, gets at the gender and socioeconomic hierarchies in Odessa’s cafés, as well as their implicit middle-class respectability and Jewishness, in his novel Esther Ḥayot (1922).86 At the center of the novel is Esther, a young, married, Jewish woman from a small town in the Pale of Settlement. Locked in an unhappy married life, she decides one day to leave her home and family and to follow her younger sister, Hanna (Anna Avramova in Russian), to Odessa. In the big city, Esther lives in a room of a hotel and meets various men, who show interest in Esther or in her sister. One of them is the young Russian Adolf Grigorovich, “a native Odessit and the loyal, loving son of the city.”87

Adolf takes Esther and her sister Hanna for a walk in the boulevards of Odessa, and in no time, they arrive at Café Fanconi. Seen through the eyes of the poor migrant Esther, from whom the author keeps an ironic distance, the café, as the city itself, is a complex thirdspace of appearances and mirrors that needs to be deciphered: “When the doormen opened the doors of the café, it seemed to Esther for a moment that the doors of new life had opened.” Esther recognizes that “all the smiles, politeness and gentility were, of course, a matter of transaction, and yet the sham was not too jarring to her heart,” for “in the café the deceit was elevated here to the level of truth.” Unused to café life, for Esther, “the mundane is transformed and elevated into a holy day.” This passage highlights the considerable currency of bourgeois appearance in Odessa and its cafés. Fashionable clothing, traveling in a carriage, shopping at an expensive boutique, and going out to a chic café were part and parcel of the city’s “respectable” lifestyle. And yet, as Esther notices, the café was also a place of social transactions: “Surely there was some order here, but the hierarchies were fluid. Each person here was a guest but also owner. Everything was different.”88 As a Jewish woman in Odessa, Esther learns that in the mirror house of the café, the social order can be, to some degree, suspended, though it is unlikely to be completely upended.

The second part of the novel, in which the two sisters, Hanna and Esther, wander through the streets of Odessa, suggests how the fluidity of social order in the café may enable, at least on the imaginary level, an indeterminacy of gender identities and hierarchies. The sisters, having become wary of the men they know, imagine themselves to be “Cavalier” and “Dame”: “Let’s walk around Deribasovskaya Blvd. without any men; leave them alone. Later we’ll walk to Café Fanconi and catch a table. I will smoke a cigarette … and invite ‘the dame of my heart,’ feed her with pastry and chocolate … just like a man.” As female flâneuses, the two sisters, who imagine themselves as a couple, make their way to Café Fanconi, drink hot chocolate, and read the newspapers, which are full of sensational stories about strange events and adventures in Odessa. But when they leave the café, the potential narrative energy of their imaginative release is immediately restituted when they meet a new man, a medical student, who invites them to his “regular table” in the more fashionable and more “exclusive” Café Robina.89

On the one hand, Steinman seems to articulate a critique—very common in the journalistic and literary writings of Odessa in this period—of the “ladies’ chatter” that ridicules their attempts to appear “cultured.” On the other hand, the femininity and the provincial Jewishness of Esther and her sister, which the narrator never lets the protagonists or the readers forget, also act as a double-edged sword. If the café is chiefly a masculine, bourgeois domain, to which urban men can chivalrously invite their “ladies,” it also enables the two sisters to enact a performance of gender that exposes its social conventions. The space of the café becomes, by the 1910s, a site in which the identity of the “New Jewish Woman” is enacted and examined. It is a mirror that reflects and sometime distorts her social, personal, and gender identity, her passions and desires, which are both real and imaginary, public and private.

World War I, Sovietization, and the Cafés of “Good Old Odessa”

When World War I was declared in 1914, Odessa was far away from the major battlefields. There was an attempt by the Ottoman Empire, which joined forces with Germany, to attack Odessa’s port, but it was not successful. During the war, the city lay near the geographical intersection of the Russian, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian Empires, and business was continually interrupted; but the city itself was unperturbed. Ya’akov Fichman, a Hebrew poet who lived in Odessa during the first years of the 1900s, came back to the city in 1915 and observed that Odessa during the Great War was “calmer and quieter than the day it was established”: “The deserted port seemed as if it stretched to the eastern horizon.… The city itself was full of life. The cafés were full of people.… The War years—I am afraid to say—were the most carefree years in our life.”90

Even amid the war and during the 1917 revolution and the civil war that erupted in Russia, Odessa did not experience the widespread violence that convulsed much of Ukraine and the Russian Empire more generally. However, the city passed back and forth nine times between Russian “Whites,” Ukrainian nationalists, the French, and the Communists. Soviet control was consolidated in 1920. Between 1917 and 1919, it seemed like a Jewish renaissance was about to take place in Soviet Russia; Odessa, which, as we have seen, was always a stronghold of Hebraists, produced 60 percent of all Hebrew books published in Russia. However, the situation changed rapidly. Soon Jewish schools, synagogues, and other religious groups, including nearly all non-Bolshevik cultural institutions, were closed. The Evsektsiya (Jewish section of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union) waged campaigns against persistent ritual customs such as circumcision, as well as against Hebraists. Almost all Hebrew and some Yiddish writers left Odessa in 1921, after Hebrew was declared a “reactionary” Zionist language in the Soviet Union. Many of them found new homes in Berlin, New York, and Tel Aviv.91

However, Jewish creativity in Russian and Yiddish did not come to a halt, nor did the world of the Jewish café culture disappear immediately. During these tumultuous years, an extraordinary group of Jewish Odessan writers and cultural figures who wrote in Russian appeared on the horizon. They became, for the first time, a dominant force in the Russian literary and cultural sphere. Many of these young Russian writers, Jews and gentiles, created the Kollektiv poetov (Poets’ collective), an informal club that met in the cafés, as well as in private apartments. Among its members were Lev Slavin, Eduard Bagritsky, Valentin Kataev, Yuri Olesha, Semyon Gekht, Ilya Ilf, and Evgeny Petrov. The young Isaac Babel, who was associated with the group, boldly declared in his 1916 sketch “Odessa” that “this town has the material conditions needed to nurture, say, a Maupassant talent.”92 Babel and his friends fulfilled the promise. The important Russian critic Victor Shklovsky called this group of writers “the Southwestern School” of Russian literature. Some of them were Jewish by birth and upbringing, and some were not; some lived in Odessa, and others left it for Moscow or St. Petersburg (renamed Petrograd). But they all absorbed a common Odessan atmosphere, which included strong Jewish undertones.93

The most prominent articulations of Odessa’s café culture during the chaos of war and revolution are found in the writings of Babel, who was doubtless Odessa’s most important Russian modernist writer. Babel was born in the Moldavanka in 1894, but soon after his birth, the family moved to the nearby town of Nikolayev. In 1905, they returned to live in the center of Odessa. Much of Babel’s writings, including the famous “Odessa Stories,” are based on his experience of the city between 1905 and 1915. Babel lovingly evoked the city and its cafés in an Odessan-Jewish style that constantly made use of Yiddish and Hebrew expressions and “types,” such as the luftmensh, the rabbi, and the good-hearted swindler.94 Babel wrote about the humor of Odessa that developed in the city’s cafés, as well as the characters he saw and met in them—from Benya Krik, the Jewish gangster, to middle-class merchants, aspiring writers, fashionable women, and such people as cross-dressers—who constantly traversed the social and cultural borders.