Читать книгу Ties that Bind - Shannon Walsh - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2: WITH FRIENDS LIKE THESE: THE POLITICS OF FRIENDSHIP IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA

ОглавлениеSISONKE MSIMANG

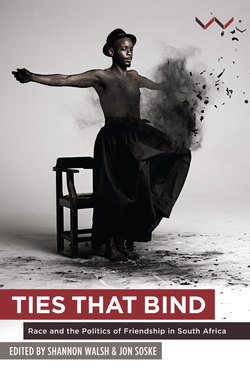

This research took the form of many late nights grappling with texts, everything from social network theory to studies on urban space and planning to philosophy. What it produced is fairly unique, part of a growing genre known as documentary theatre.1 I have taken verbatim the words of people such as Sindiwe Magona, Njabulo Ndebele, Dennis Brutus, Zama Ndlovu, Sekoatlane Phamodi, and many other South Africans who are thinking publically about the problems South Africa faces and the dreams we must embrace, and I have asked Lebo Mashile, one of our country’s most important contemporary poets, to perform them in order to make them visual.

I chose this methodology because I wanted us to remember that we have already written many, many important things about race and justice and humanity in this country. I also chose the documentary theatre genre because here in South Africa fact is often stranger and more poignant than fiction. In this context, performing real words on a stage forces us to confront their importance and it moves us beyond business as usual.

Lastly, I chose this genre because I wanted to signal that there is a new generation of contemporary thinkers: people such as Milisuthando Bongela, Danielle Bowler, T. O. Molefe, and others who are cited here, whose words are as much a window into this country’s collective soul as those of Gordimer or Coetzee or Paton.

Now that the season of realpolitik is upon us and the rainbow myth is receding we must ask ourselves whether we still need a framework of reconciliation that presupposes friendship across the races as an important and useful barometer of the health of the nation.

Some will argue that the question of friendship is frivolous. They will say we must be more concerned with matters of politics and economics than of emotion, and that we don’t need to be friends; we simply need not to interfere with one another’s destinies. Others will insist that we must indeed be friends. They will wring their hands and argue that to abandon the idea of friendship is to abandon an important national ideal and perhaps to abandon a peaceful future.

Perhaps counterintuitively we must hold on to both instincts. On the one hand, our progress in improving the conditions of black people must be central and must be guided not by a desire for blacks and whites to be friends, but by the need for black people to live dignified and equal lives that are commensurate with those of their white compatriots. In defence of this, we must be prepared to alienate whites (and for that matter blacks) who do not accept this as a fundamental reality. We must accept that they might leave and seek their fortunes elsewhere and this must not concern us.

On the other hand, we must accept that although the notion of inter-racial friendship has sometimes threatened to overshadow the importance of black dignity, it is crucial that we keep its possibility alive, even as we tend to the more urgent matters of preserving and elevating the meaning of black personhood because this is the basis upon which a genuine and robust culture of respect in contemporary South Africa will be built.

To even begin to talk about interracial respect in modern South Africa is difficult because so much unintentional damage was done by our country’s first iteration of reconciliation; what I refer to as Reconciliation 1.0. There were many flaws in that first version. Yet in light of palpable anger and discord on race in recent years, we have a new opportunity to develop a more honest code: call it the open source version. Indeed the seeds of this are evident in the activism that swept our country in 2015. South African students are at the forefront of designing the upgrade, and the next generation will owe them a debt of gratitude.

Ironically, perhaps, in thinking about how we deepen this new code we must stretch our minds back to ancient times, to the Greeks, to Aristotle in particular. For Aristotle, philia was the most perfect form of friendship. The great philosopher suggested that there are three kinds of friendship: friendships of convenience, where the parties interact, for example, in order to do business or Black Economic Empowerment deals; friendships of pleasure, where if the pleasurable thing, say drinking or smoking crack, disappeared, then the friendship would too; and friendships of character, in which ‘one spends a great deal of time with the other person, participating in joint activities and engaging in mutually beneficial behavior’.

In this view: ‘Between friends there is no need for justice, but people who are just still need the quality of friendship; and indeed friendliness is considered to be justice in the fullest sense.’

In other words Aristotle argued that between real friends, there is seldom need for the interventions of outsiders; justice is made possible by the nature and depth of the relationship. In short, where there is trust, there is no need for strongly enforced rules. By extension then, those who consider themselves to be good and moral cannot be truly good or moral if they do not have the ‘friends’ to prove it.

For the white South African, who is surrounded by millions of black potential ‘friends’, the implied question in Aristotle’s framing of the relationship between friendship and justice is, ‘Are you just?’

Because of our history, this moral and practical question is especially directed at white people. Friendship should and must be of great ethical and philosophical concern for whites. In general, white people in this country should worry and be pained by this matter in ways that black people need not be, for obvious reasons of demography and history.

If we are to replace the distorted and falsely optimistic vision of the rainbow with a more honest but no less aspirational vision of dignity and respect, whites will need to give up their ideological and practical specialness and they will also have to reject the increasingly irrelevant, weepy, and unhelpful mythology of Rainbowism. Those who are truly invested in the future of this country will also have to stop hiding behind their emotions and their tears whenever the subject of race comes up.

One of the tenets of the rainbow era was that those of us who extended our hands across the racial divides were thwarting racism. If the racist hates it when children play together, then surely those of us who encourage our children to interact are not racist?

Unfortunately it is not so simple. Friendships involving people who are more powerful than us have seldom served black people well. The power imbalances are too great, the possibilities for manipulation and domination even by those with good intentions are simply too high to assume that light friendship is the answer.

Today, a generation into democracy, young black people raised to believe that friendship across the races is an indicator of progress are questioning this. They are asserting that friendship, if you want it, is not free of responsibility. Some of them are going further to say that friendship is simply not on the cards for them.

In a South Africa trying desperately to figure out a way forward these assertions are not easy to speak aloud. Yet they represent a recalibration of our aspirations. Some people are worried by this: They are scared of what they call ‘separatism’.

I am not, mainly because this sort of robust honesty does not mean that we have abandoned the idea that ‘race’ is empty a construct that should neither bind nor divide anyone. We can both believe in the need for a just world in which race is meaningless, and accept that in this time and place, ‘race’ is a term that is bursting with meaning.

Can we be friends across these ‘racial’ boundaries? Yes, we can. And No, we cannot. It’s that simple and that complex. It is the struggle for understanding the complexity of this paradox that must enthuse and inspire us.