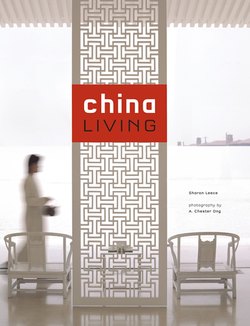

Читать книгу China Living - Sharon Leece - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеback to the future

These are exciting times in the new China. Since the opening up of post-cultural Revolution China in the late 1970s, followed by the building boom of the 1990s and early 21st century, the country has changed immeasurably as huge economic and social transformations have swept through every aspect of life. In this rapidly developing nation, the pioneering spirit of a buoyant economy and a desire to embrace new opportunities is manifesting itself in innovative interior design and architecture projects.

A seemingly insatiable appetite for the new is leading architects and designers to take a forward-thinking and often visionary approach to their work. Almost overnight, gleaming skyscrapers are transforming the skylines of major cities with high-rise apartment blocks and office towers replacing traditional structures. One need only look at the statement-making architecture that is being constructed in Beijing for the Olympic games in 2008 to appreciate the desire of the country and its citizens to create a world-class environment presenting the face of modern China to the world.

One thing is for sure—in the midst of such great change, the only thing that is predictable is change itself. A lack of inhibitions means that in design terms almost anything goes. Whilst this may cause more conservative types to shudder, it allows room for fresh inspiration and creativity. With China’s first generation of private architectural firms starting up as recently as the early 1990s, it comes as no surprise to see how this new change of pace is driving the desire for design to reinvent itself in this country.

Of course, in the race to build quicker, better, bigger, the results are not always positive. Sometimes the sensitive and the discerning are eschewed in favor of poorly planned and built developments. Critics also say the country’s heritage is being lost in the race to embrace the future; although advocates say they are building a better life for the county and its citizens. But what is becoming clear in the midst of all this rhetoric is that a small but increasingly high-profile group of architects and designers is carving a path which focuses on quality design. And their bold statements about the future of Chinese design are now unfolding across the nation to increasing critical acclaim.

By infusing their work with a fresh vision that is totally Chinese in its essence and yet thoroughly international in its outlook, these architects and designers are busy creating a body of work that is global in its appeal even though it is rooted in local conditions. This work is often highly personal in nature, valuing the environment and incorporating local construction techniques and materials. It respects the past while looking to the future to create a new design aesthetic. This book presents the diverse landscape that is China today and in so doing explores a wide range of innovative new projects. From modernist mountainside villas to high-rise city apartments and artistic retreats in refurbished industrial zones—the array of modern living options in China is as diverse as the country itself.

Villa Shizilin outside Beijing (see pages 164—175) was designed to create a dialogue with nature. Set in beautiful grounds complete with a swan-filled lake, the tapered rooflines of the house echo the mountain ridge above it. The use of local stone and glass enables the building to sit almost camouflaged against the natural backdrop.

An antique daybed, sourced in Gao Bei Dian in Beijing, and a silk standing lamp designed by Robarts Interiors and Architecture stand in front of embossed leather wall panels at McKinsey & Company, Beijing (see pages 58—63).

One of the distinguishing characteristics of contemporary Chinese design is its thoroughly global outlook. Globalism is fast permeating all aspects of modern Chinese life, and designers such as Beijing-based Wang Hui feel that good design comes out of this cosmopolitan approach. “It’s a kind of exchange,” he explains. “If you only think about things in one way it is kind of limited; fresh information gives you new points of view from which to think about design.”

With Chinese architects now having access to the world’s top architecture schools and big-name foreign architects opening practices in the country, incredible new synergies are playing themselves out. It is the new generation of Chinese architects who are able to see their own culture from both within and without and are thus able to reconnect with their roots in an international context. No longer is “Chinese design” traditional; on the contrary, the parameters of the genre have been intentionally blurred in a bid to meet the needs of modern clients. Traditional influences are lowkey, rather than overt. Says Wang Hui: “The culture is already in my heart. Through design, I prefer to use it in subtle ways.”

Experimentation is now at the forefront—with traditional materials and techniques being radically adapted to modern purposes. Structures such as the villas by Yung Ho Chang and Chien Hsueh-Yi at the Commune by the Great Wall and the award-winning Villa Shizilin by Yung Ho Chang and Wang Hui near Beijing, take a natural approach—using timber, compressed earth and local stone—and in so doing respect the history of the land to blend in seamlessly with the environment.

Such villas weave in many outside influences (designer and antique furnishings, space-making technologies and modern global comforts) yet remain rooted in their Chinese locality and sensitive to their surroundings. Today’s Chinese architecture is modernist and minimalist, yet the materials used lend rawness and texture, reflecting a sometimes contradictory dialogue between austerity and luxury which has come to define many new designs, especially in and around Beijing.

Such a dialogue says as much about the Chinese psyche—especially within the thriving artistic community—as it does about new design influences. What can be seen today is not just people’s desire to push traditional boundaries and enjoy an enhanced standard of living but also a pent-up need to express creative aspirations through design. In Beijing, many of the architects, artists and creative types who are making news are self-taught practitioners who take quirky, non-conformist approaches to their work. A new, self-styled struggle is evident with few rules or restrictions holding them back. To be too comfortable would perhaps blunt the edge of innovation and hinder the quest for the new.

It is not just in Beijing—with its modernist, creative tension and aura of austerity—that boundaries are being pushed. In Shanghai, where the pace has been hard and fast and energy levels extraordinarily high, a tentative balance between heritage architecture and modern skyscrapers is still being struck. Design in this cosmopolitan, forward-thinking city is both heady and glamorous, emphasizing style and opulence, in contrast to the northern capital. Design directions in Shanghai are rooted in the city’s multi-cultural history and delivered through its global commercial outlook.

Shanghai, like many of China’s other major cities, is experiencing a building boom which has created new suburban centers, with villa developments ringing the city. Whilst styles vary, the most successful developments take inspiration from traditional architecture, with designs that renew the age-old Chinese dialogue between interior and exterior space. The classic Chinese courtyard house, the siheyuan, is a prime example of a traditional residential model that is being reinterpreted in novel ways.

James Law’s Hong Kong home (see pages 124–131) is intelligent enough to interact with its user. Flexible animatronic walls and partitions, digital wallpaper, a cyber butler and video conferencing capabilities allow real space and cyberspace to merge.

In Beijing’s Mima Café (see pages 186–189), Wang Hui created a 15-square-meter (161-square-foot) “vanishing” stainless steel cube in the courtyard containing a kitchen and bathroom. The design is in part a response to regulations demanding that any architectural work here should not compromise the spirit of the surrounding buildings.

Respect for history and the traditional family living arrangements is being increasingly recognized in this new architectural movement as thoughts turn from chai (demolition) to bao (preservation). There is a realization that new is not always better when it comes to redevelopment. “We want to remind people how to bring older elements into a contemporary environment,” says Daker Tsoi of The Lifestyle Centre, the developer behind The Bridge 8 complex in Shanghai—a former automotive plant that has been reconfigured as a creative retail and working space. “We always keep in mind that developing so-called Chinese culture is not just about taking an old drawing or just putting two Qing chairs in your living room. Rather it’s about how people live, the size of the streets, the spatial rhythms and what they feel comfortable with. These are interesting elements that can be brought into contemporary architecture to represent China.”

In Hong Kong—one of the most exciting and vibrant cities in the world—residential design continues to push new boundaries. Leading designers here are creating homes with global appeal, applying new technologies and design concepts like nowhere else on the planet. Especially popular are homes providing new solutions for urban living in compact spaces. As befits a multi-cultural and international city, the people behind the projects come from varied backgrounds and are producing design directions that draw on their own individual experiences and world vision. Style and sophistication are the key, with inspirations from the classical Chinese attributes of balance, order and harmony being reinterpreted with a modern twist.

For the purposes of this book, contemporary Chinese design and architecture have been divided into four sections or “schools”—each revealing a different approach. “New Creativity” explores the work of designers who are revisiting classic Chinese motifs and architectural forms to produce elegant new spaces that are minimalist yet imaginative. Each project takes its inspiration from Chinese culture and art, reworked in a sophisticated manner to be compatible with modern living requirements. Highlights include a stark white stone pavilion by Beijing-based designer, master chef and musician JinR; a clean-lined villa by Clarence Chiang and Hannah Lee; and a garden courtyard house by Rocco Yim.

“Urban Innovation” focuses on forward thinking, cutting-edge urban interiors. Energetic, inspirational and progressive, these projects subtly hint at cultural origins yet look firmly towards the future. City apartments such as those designed by Darryl W. Goveas, Ed Ng, Gary Chang and James Law reveal how innovative materials, flexible spatial transformations and the latest in cyber technologies can produce new and exciting residential interiors.

Experimental designs take precedence in “Elemental Appeal”, which reveals how architects, designers and creative thinkers are pushing beyond established boundaries to create residences that favor function over luxury, innovation over tradition. Such unconventional approaches to design embody a respect for the past— simplicity of form, sense of craftsmanship—but they juxtapose the traditional and the modern in an un-inhibited way that often borders on the austere. The modernist influence is strong and homes featured include art collector Guan Yi’s residence containing his huge collection of contemporary installation art and Ai Wei Wei’s austere grey brick duplex, now home to photographer couple RongRong and inri.

By contrast, “City Glamour” focuses on cosmopolitan inner city residences full of vision and flair. Here, Chinese and global elements combine with panache, infusing classic inspirations with contemporary textures, colors and patterning. Examples include Kenneth Grant Jenkins’ geometric art deco duplex; Kent Lui’s inside-out apartment and Andre Fu’s Peak apartment full of lacquer finishes, wood veneers and Chinoiserie-style fabrics.

Such breath of vision, in all its permutations, reveals a single truth about Chinese design today: that the pace of change is every increasing. Freed from rules and restrictions, designers are now able to absorb influences from every quarter and chart their own path. The groundwork for the future of Chinese design is being laid today.

Gary Chang's Suitcase House at the Commune by the Great Wall (see pages 176–179) soars over the sloping terrain. The 40-meter (130-foot) rectangular box structure is a steel frame clad with teakwood from Western China.