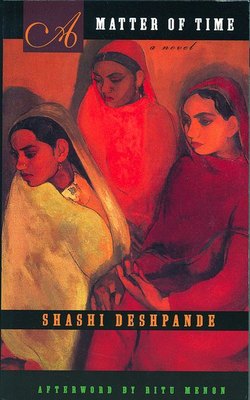

Читать книгу A Matter of Time - Shashi Deshpande - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGOPAL, WHO HAS had no intention of making a mystery of his whereabouts, is living scarcely a few miles away from Sumi and his daughters in the house of an old student of his. This is in an old part of the town, where tiny lanes criss-cross one another and homes, small shops and restaurants jostle together in a jumble of noisy existence. Gopal’s room, above the printing press that belongs to his student, is an odd place for a man to ‘retreat’ to—the thought will occur to all those who visit him. But like the truck drivers, who, after a night of frenetic driving, go to sleep in the womb-like interiors of their driving cabins, wholly insulated from the outside world, Gopal is unaware of the jangle of noises in which he is living his life.

Now the interlude of peace suddenly ends for him. Shankar, still the student, unwilling to sit down in Gopal’s presence, is there to tell him that Ramesh had rung up.

‘And you told him I was here? It’s all right, I never wanted to hide the fact from anyone.’

So Ramesh has traced me here. I should have guessed he would be the first; he has his mother’s doggedness, his father’s sense of duty. And so, he will be the first to ask me the question, ‘Why did you do such a thing, Guru?’

I had prepared myself for this question, I had rehearsed my answers before I spoke to Sumi, I had been ready to counter her arguments. Now I have to be ready to face Ramesh, I have to brush up my reasons, for Ramesh will not let me off easily. What do I say? What were the lines I had prepared?

I heard a voice ....

No, I can’t say that, it sounds utterly phoney. Even Joan of Arc didn’t get away with that one.

It’s a kind of illness, a virus, perhaps, which makes me incapable of functioning as a full human being, as a husband and father ....

This is the right answer to give a doctor and Premi may accept it, but will Ramesh? No, he won’t leave it at that, he will ask me for my symptoms, he will try to connect them and ultimately, yes, I’m sure of this, make an appointment for me with a psychiatrist. No, best leave this alone.

I thought of Purandaradasa’s line, ‘Listen, the hour strikes’ and I was terrified, I knew I was running out of time.

Sumi is the one person who may understand this, she will know what I mean. But this is not enough; I have to be more honest with her, more explicit.

What then? What do I say?

I stopped believing in the life I was leading, suddenly it seemed unreal to me and I knew I could not go on.

Is this the truth? Is this why I left my home, my wife and children? Could I have said this to Sumi?

In the event, there was nothing for me to say to Sumi, for she asked me nothing. I am thankful I never had to suffer the mortification of wading through this slush of embarrassing half-truths. I have not been fair to Sumi, I know that now. I should have spoken to her earlier, given her some hint of what was happening to me. But how do you interrupt the commonplace with melodrama? There is never the right time in daily life for these things. The knock on the door, the peal of the bell bringing news of disaster, they can only come from the outside.

Since coming here, I have been dreaming of my father. How do I know that the man I see in my dreams is my father? I was only eight when he died and nothing of him has remained with me, neither his face, nor his voice, nor his manners, nor any memory linking the two of us together. Just a blank. It is odd, yes, when I think of it now, I realize how curious it is. Can one erase a parent, even a dead parent, so completely? To some extent, of course, Sudha was responsible for this. She put away everything that was our parents’, even their pictures, immediately after their death. I accepted it then, but now, thinking of it, I can imagine that she must have worked in a frenzy, sweeping the house bare of their presence. And I know this too now, that she did it for me. It was this, and her almost immediate marriage to P.K., that helped the quick transformation of a house of mourning into a normal home in which a family lived. Man, woman and child. P.K., Sudha and I. And so I forgot, how quickly I forgot the faces of my parents. No memories at all. Except that, sometimes, when Sudha laughed, it seemed like something I had heard once.

And yet, I am certain that the man who visits me in my dreams is my father. The knowledge belongs not to me, the man that I am now, but to the I-figure in my dreams, that disembodied self who is always a boy. This father of my dreams smiles at me, we walk the streets together, he waits for me when I lag behind, he holds my hand when I’m tired, he looks at me affectionately ....

I know, of course, what it is I’m doing: I am recreating my father in my dreams as I had done in my waking hours, all those years ago, as a boy. Inventing him. Knowing nothing about him then, except that he had married his brother’s widow who became my mother; the possibilities had been innumerable and my adolescent mind had drawn various selves out of the protean being of the father I had imagined. So many of them:

A man who sinned against his brother by loving his wife. The brother dying of grief and the wife and the man marrying immediately after.

A kind man moved by pity to marry his brother’s widow, to make that brother’s daughter his own.

A Lakshman-like younger brother, keeping a promise made to his dying elder brother to look after his young widow and child.

(No, this never worked. Lakshman, who never looked at Sita’s face, not once, so that the only bits of her jewellery he could identify after her abduction were her anklets—this devoted brother had to be discarded.)

It was when I read Hamlet, fortunately much later, that the most terrible version of my parents’ story entered my mind. Just that once, though, for I slammed the door on it immediately. In this story my father became a man succumbing to his passion for his brother’s wife, the woman compliant, a pregnancy and a child to come and then, after the husband’s convenient death (no, I couldn’t, I just couldn’t make my father poison his brother) a marriage of convenience.

The facts, of course, few as they are, spell out a different story: Sudha’s father died of typhoid and I was born two years after my parents were married.

But that was how it was for me—my father was never a father to me—not after I knew their story. He was my mother’s guilty partner, he was Sudha’s uncle, her stepfather, he was my mother’s husband ....

And now I dream of this kindly man, as if we have, through the years, achieved a kind of peace in our relationship, as if, like any son with a living father, we have finally, after a long struggle, achieved a harmonious relationship.

These are peaceful dreams that don’t trouble me—unlike the ugly dreams that tormented me in the last few months before I came here, exhausting dreams that seemed to go on all night, punctuated by the need to empty my bladder. So exhausting that once, waking up, I had been astonished to see that it was only fifteen minutes since I last woke up; those fifteen minutes had seemed a weary lifetime.

All a thing of the past. Now there is only this room in which nothing is mine. For a few days after I came here, I heard Shankar and his wife trying to hush the children and servants; but the noise and bustle in the courtyard do not disturb me, they have nothing to do with me. Like the rain-trees on the road outside, so very mysteriously, wonderfully flourishing in this human jungle, which seem to have raised themselves above all the futile activity on the road below, I am untouched by all that is happening under my window.

Yet sometimes, when I wake up in the morning and see the branches of the rain-trees filling up my window, I feel I am back in that tree-enclosed room of the outhouse behind Kalyani’s house. I hear Shankar’s wife call out to her children and it is Kalyani’s voice calling out, ‘Sumi, Premi’.

Yes, I was at peace then too, like I am now. Sudha, absorbed by her young children had freed me from the tug of her concern, I had moved away from Shivpur, from Girija and a relationship that had been threatening to complicate my life. In the outhouse I was left alone, set apart from the Big House by much more than the physical distance between us. It was as if the mist that sometimes came down in the mornings, never lifted, so that the figures I saw seemed always hazy, the voices muted and muffled, coming to me from some great distance. I watched them, after a while it became a pastime, but there never was a sense of involvement. There was the man whom I rarely saw after my first meeting with him, coming out onto the terrace, standing there, gazing at nothing. My landlady, whose tense, small figure advanced towards me in a burst of cordiality, then retreated just as abruptly. The younger girl, sitting on the side steps, silent as a wraith, her knees drawn up to her chest, squeezing herself into the smallest space possible. And the older girl ....

Years later, when we went to Abu, I saw the richly draped idol of Parvati, glowing with colours among the cold, white, marble figures of the Tirthankaras in the Dilwara temple. Sumi was like that, drawing all the colour and movement in that house into herself. She filled me with the same astonishment and delight that the idol of Parvati in the temple had.

I can still remember the day my detachment ended. I woke out of a heavy drugged sleep in the afternoon—it must have been a Sunday—to the sound of girls’ voices. I went out to the tap to wash my face and saw them, Sumi and a friend, on the stone seat under the neem tree. I went back to my room, picked up my book and tried to go back to reading, and the voices and laughter came to me still, like a distant melody, filling me with ecstasy. I ceased to be an observer then and, like the king who stood watching Shakuntala and her two friends, I became part of the enchantment, I could see the bee hovering, I could hear its buzzing ....

‘We are searching for the truth; you, O bee, have found it.’

Found it? Yes, for a while it was that way. After years of blundering I had found the truth in my feelings for Sumi, my love for my children. But now I know I had only lost myself in that beautiful, dense green foliage.

Can I say this to Ramesh? No, he will never understand me. Ramesh is the son of P.K., a man whose sense of duty and responsibility was absolute. And yet, after his death, when the crows would not come for the pindas, the priests said, ‘He must have left something undone.’

‘Men don’t die easily, Guru,’ Ramesh had sobbed out to me when, as an intern, he had lost his first patient. ‘Men don’t die easily.’

Is there to be no end to it even after death? Was a man to be tied to his duties forever? Could he never be free? It astonished me that Ramesh so tamely made a promise to his dead father, as they told him to do, to complete whatever was undone. He squared his shoulders and accepted his father’s burdens. He will do the same now. He will not despise or hate me, the bond between us is too strong for that. Instead, he will make up his mind to take on the responsibility of my family on himself. And then, only then, he will tell Sumi where I am.

It is not Sumi, however, but Kalyani who is the first to come to Gopal. ‘There’s a lady come to see you, sir,’ the press boys tell him and he thinks it is Sumi. But it isn’t, it’s Kalyani. For an instant, perhaps because he has so rarely seen her outside her own home, he does not recognize her. She looks a different person in these alien surroundings. Was she always so tiny, so frail-looking? Charu is with her, Charu who makes it absolutely clear that she is here only as her grandmother’s escort. Scarcely looking at her father, she helps Kalyani up the stairs and saying, ‘I’ll be waiting downstairs for you, Amma,’ prepares to leave.

‘Don’t go, Charu, stay here.’

‘Let her go, Gopala. Go, child, I won’t take much time.’

‘Come out here then.’

He shows her out through the narrow door, into the small terrace behind the room and then hesitates; it’s too sunny here, there is no shade at all. But Charu, her back to him, goes and stands near the railing, ignoring him.

The moment he comes back into the room, Kalyani bursts into words.

‘What have you done to my daughter, Gopala, don’t do this, don’t let it happen to my daughter, what happened to me.’

And then she stops, abruptly, a hand to her forehead, as if rebuking herself. This is not what she had intended to say! She begins again, this time saying the things she has come prepared with. She calls him Gopala, dragging out the last vowel, loading the name with affection and tenderness. He is amazed that she speaks without hostility.

‘When Sumi married you, she was too young; but I was not anxious for her, you were older, you were sensible and you cared for her, yes, you did. I can still remember how you scolded me for being angry with her when she refused to nurse Seema. She can’t help it, Amma, you said to me, she isn’t depriving the baby of milk on purpose. How can you change so much, Gopala?’

She goes on, moving from surmise to surmise. Has anyone poisoned his mind against Sumi? Has she done something wrong? Can’t he forgive her? She knows—and she says this placatingly, so humbly that it hurts—he is a generous man. And Sumi too—he shouldn’t think that her friendliness with others means anything.

‘Amma, it’s not that, I know Sumi ....’

But she doesn’t let him speak. I know she was careless, she says, I know she didn’t bother too much about her home, ‘But, Gopala,’ and now she hesitates, ‘how could she have known what being a good wife means when she never saw her mother being one? I taught her nothing, it’s all my fault, Gopala, forgive me and don’t punish her for it.’

Once again he tries to tell her that he has nothing against Sumi, he tries to convince her that he never expected her to create for him the world he wanted, that he did not make her responsible for giving him all that he wanted in life, but Kalyani hurries on.

‘Is it money, Gopala? If it is, you know that Sumi and you will have everything of mine. Premi is comfortable, I am not worried about her. Even my jewellery—most of it is for Sumi ....’

This time he does not have to speak. She looks at his face and stops. And begins to cry. He watches her distress helplessly.

‘Look at me, Gopala,’ she says when she can speak. ‘My father died worrying about me, my mother couldn’t die in peace, she held on to life though she was suffering—she suffered terribly—because of me, she didn’t want to leave me and go.’

She is crying uncontrollably now, she can’t speak. And so he does. He tells her that this has nothing to do with the relationship between Sumi and him, it has nothing to do with Sumi, she has done nothing wrong, she has done him no wrong, on the contrary, it is he ....

Listening to him, she begins to understand that nothing she says can affect him. He can see the anger rising in her, anger she tries to conceal, afraid, perhaps, that she will alienate him by that. Once again, this hurts.

‘What about your daughters? Have you thought of them? Look at that girl standing out there—she didn’t want to come, she came here for my sake. Have you thought of what you have done to them?’

‘I thought of everything before I took this step. Do you think, Amma, I haven’t?’

There is a long silence after that. Then Kalyani stands up.

‘Charu,’ she calls out.

Charu stands at the door, blinking, trying to adjust her eyes to the dimness after the strong light outside. She gives Kalyani a quick look, taking in the fact that she has been crying, but she says nothing.

‘Let’s go, Charu.’

‘I’ll get an auto, you wait here, Amma.’

‘No, don’t, Charu. Let’s start walking, I’m sure we’ll get one on the road. We will, won’t we?’

Before leaving, she looks about the room for the first time since she had come in, taking it all in—the thin mattress rolled into a dingy striped carpet, the rough wooden planks of the bed, the bare table, the string on the wall on which he has hung a towel and a shirt ....

‘You live here?’ she asks him.

‘Yes.’

‘And who’s this Shankar?’

‘A student of mine.’

‘Oh!’

She is no longer able to sustain interest in anything. The purpose that had upheld her when she came has receded from her. She goes down the stairs like a woman much older than her years, putting both her feet on a step before going to the next one. Charu follows, her dupatta trailing on the floor behind her as usual. Gopal has an urge to pick it up, to put it back on her shoulder, but as if she has guessed his thoughts and wants to forestall him, she picks it up and adjusts it herself. Watching his daughter move away from him, he has a sense of loss so acute, it is like a physical pain. Unable to follow them, he goes back to the room and sits down, listening to their steps recede.

This is part of it, I have to go through all this, I cannot escape. What had I expected, that I could inflict pain and feel none in return?

If Kalyani came as a supplicant, Aru is an adversary, holding her hostility before her like a weapon. A sword, scrubbed to a beautiful silvery sheen, sharp-edged, ready for war. She is determined to behave like an adult, or rather, as she imagines an adult should be—cool and reasonable. She asks the polite questions of a visiting acquaintance, about this room, about Shankar, his press and what work does he do there? He imagines that this is the way a prisoner would feel with a visitor—uneasy, longing for it to be over. He can see the effort she is making, he wants to tell her to stop, he would rather see her grief and anger pour out of her; but she holds him at bay, she won’t let him do anything but reply to her questions—until her questions finally peter out and they are left in silence.

‘Papa,’ she begins, then stops as if this is not how she wants to address him. But the word has opened a valve and now it gushes out. The confusion in her mind is reflected in her language—she skips from Kannada to English and back again, her sentences incomplete, leaving out words that she can’t get hold of. Her voice rises, trails away, suddenly becomes gruff and guttural as if something is choking her.

And then she can’t go on any longer; she breaks down and begins to sob. But there is no relief in this outpouring, either; she fights against it, her body shaken by the effort to control herself. He gets her a glass of water, tries to make her drink it, but like a petulant child she pushes his hand away. The water slops over, spills, drenching her skirt, his trousers, yet he continues to hold the glass before her until she hiccups herself into silence, wipes her eyes and drinks the water.

But it is not over. She begins again. And this time, like a surgeon who has opened up a patient, she begins to probe, knowing it is there, the tumour, knowing it has to be found and removed for the patient to survive.

Is it because of something Sumi did, something she said? Is it because of us, because of me? Is it because I was rude to you, because I always argued with you? Is it because of what I said to you when you decided to resign? Is it money?

He can see that his silence, his negatives, drive her to desperation and she goes on to memories: ‘Do you remember, Papa?’ This time the appellation comes easily, she is unconscious of it.

‘What can I say to you, Aru?’

‘Say it, whatever it is, tell me, I am not a child.’

But it’s no use, he cannot give her what she wants, what she has come here for. When she gets up to go, they have both of them the same sense of failure, they are equally exhausted.

Nothing can touch me, I had thought, I’m wearing a bulletproof vest. But what do you do when your opponent comes with a knife, gets under your skin and begins to twist it between your ribs? Aru, in her anger, reminds me of Sumi. But Sumi’s anger is sharp: one clean cut and it’s over, Sumi is wiping the blade and putting it away. Aru, on the other hand, is hitting out with a blunt weapon, uncaring of where the blow falls, even hurting herself in the process. Her questions are like the Yaksha’s questions; a wrong answer will cost me my life. At one moment I almost blurted out what is perhaps the only thing I can say to her: I was frightened, Aru, frightened of the emptiness within me, I was frightened of what I could do to us, to all of you, with that emptiness inside me. That is the real reason why I walked away from Sumi, from you and your sisters.

Frightened—yes, it seems to be the truth, the right answer beside which all the reasons, all the answers I so carefully framed in the right words become so much trash, crumble into dust. It seems to me, now that I have brought it out into the open, that the fear was always there in me, submerged for a time in my absorption with Sumi and my children.

We bury our fears deep, we stamp hard on the earth, we build our lives on this solid, hard foundation, but suddenly the fears come to life, and the earth shakes with their struggle to surface. It was Sudha, the sight of her when she came to us after her illness, that brought my fear back, so close that the sound of its flapping wings filled my ears to the exclusion of everything else.

Sudha had been a vigorous, healthy, confident girl. And cheerful, yes, even after our parents died she was still that. (Or was that a facade she carefully preserved for my sake?) With marriage and motherhood she blossomed, she became an attractive woman. After P.K.’s sudden death, she looked empty, as if it was all over for her. And then she underwent surgery for her tumour. She came to us to convalesce after that, and this was yet another woman—a peevish, self-centred invalid, constantly complaining of her pains. But I, who knew her so well, realized what she was doing: she was diverting us, cleverly drawing our attention away from her real pain. It was not her illness, not the depletion of her physical self with surgery and post-radiation sickness, not even P.K.’s sudden death or the fact that he died first, when she had, with the knowledge of her cancer, expected to go before him—no, I knew it was something more than all these things that made her the way she was. She had retreated from us; none of us, not her own children, nor I, her brother, nor my children whom she so dearly loved, could reach her. And she was frightened of this world of loneliness she suddenly found herself in.

When she said she wanted to go back home, I did not try to make her change her mind. I rang up her children, and Ramesh and Veena came to take her back. We went to see her off and I knew I would never see her again. She knew it, too, but she turned her face away from us, weary, it seemed, of everything and it was left to Veena and Sumi to say the usual things. And I thought: if it can happen to Sudha, the most generous and loving of women, Sudha who invested all of herself in relationships, if this crutch of family and ties failed her when she needed it most, what hope is there for any of us? Must we reach the terrible point Sudha did before realizing the truth?

Emptiness, I realized then, is always waiting for us. The nightmare we most dread, of waking up among total strangers, is one we can never escape. And so it’s a lie, it means nothing, it’s just deceiving ourselves when we say we are not alone. It is the desperation of a drowning person that makes us cling to other humans. All human ties are only a masquerade. Some day, some time, the pretence fails us and we have to face the truth. Like Sudha did. And I.

I had a glimpse of it, not when my parents died, for Sudha was there then, she was the link that ensured the continuity of my life, and soon after, there was P.K. as well. It happened to me when I saw Sudha’s school certificate and knew that we did not share a father. That was a betrayal that cut away at the foundations of my life. Sudha never realized what this did to me. She had always known it, she said, she had not told me because—well, because my parents never had. And, she said, the truth was that she had almost forgotten that my father was not hers. He was our father, she never felt any other way.

She could not understand my reaction, she refused to accept my decision to go away, she refused to believe I meant what I was saying. When I told her I was going, she had the same stricken look on her face I had seen on her wedding day, when, bored, tired of sitting on the uncomfortable wooden folding chairs, I had walked out of the hall. She had come running out, frantic, looking garish and unlike her usual self in her wedding finery. And then she saw me, standing against a car, doodling in the dust on its surface and her face changed. But this time I was no longer a bored, confused child of eight, there was nothing I could do to wipe that look off her face.

‘Where are you going?’ she wanted to know, she had to know, and because I had to tell her something I told her I wanted to go back to Shivpur, the place my parents had come away from to escape the scandal that followed their marriage.

I had to go there after that, trapped into it by my own words, by Sudha’s insistence on accompanying me. It was she who made a crusade of finding the house our parents had lived in. It was not easy, she had forgotten everything—she was only six when they left—and the few landmarks she remembered had disappeared. But she would not give up. In the evening when we came back to the seedy hotel we were staying in, she was irritable, exhausted, but the next morning she was ready to start the search all over again.

It was on the third day—I think—that she said, ‘There it is.’ Doubtfully. Then more confidently, Yes, that’s it.’ We stared at the house. I was disinterested and Sudha listless; it meant nothing to either of us. We went back to the hotel, flat and dull and sat in silence. And then I said it, what I should have told her much earlier if I had not been too much of a coward: ‘I’m not going back to Bombay with you, I’m staying on here, I’m joining college here.’

She came out of her apathy in an instant and began questioning me: What was it? Was it something she had said? It couldn’t be P.K., he was so good he would never hurt me, no, not even unknowingly. It had to be her. But I knew her, didn’t I, she was quick-tempered, she admitted it, but surely I knew how little it meant?

From guilt I went on to annoyance and we began to quarrel, quarrels that went on and invariably ended in her desperate sobbing. I was frightened by her state, I had never seen my sister this way, not even after our parents died. I sent P.K. a telegram. He came at once with Ramesh and took charge of things immediately.

He persuaded Sudha, who had eaten almost nothing for two days, to eat and as a preliminary went to the market and got some lemons. A practical man, he bought a squeezer too, and I can remember him squeezing the juice, as earnest as any Gandhian disciple preparing for the end of Bapu’s fast, while Sudha sat on the bed, legs folded under her, indifferent to everything, even the mess P.K. was making. But she drank the juice, I was astonished to see how greedily she drank it. (Later, when Viju was born, I realized she was pregnant then, which explained some of her behaviour, though not all of it.) By evening he had persuaded Sudha to let me have my way, made her agree to go back without me.

I was frantic for them to go and leave me alone, I saw them off with joy. I can still remember the crowds and noise on the station, the sound of running feet on the platform, the last-minute desperate cries of passengers, the raucous call of the vendors—chai garam, chai chai. Then the train left and I was alone. There was nothing left but the smooth gleaming rails. And a sudden hush, as if the train had taken away all the people, all the noise with itself.

I did not go back to the hotel that night, I did not want to be there, not even for a night, in the room that seemed to be redolent with Sudha’s distress and grief. I spent the night there, on the station, on a stone platform built around a tree, watching in a dreamlike state the sleeping bundles on the floor and benches, hearing, once or twice, a child wake up and cry. Once, waking out of a doze I saw a train move out of the station in total silence, as if it was a ghost train. I got up and walked about until the first light brightened the sky, making the station lights look sickly and dim. I went then to the room P.K. had arranged for me to live in until the hostels opened. Unwashed, sleepless, I must have looked a sight, for I can remember even now my landlady’s suspicious stare. But she let me in and I went to a tap in the backyard, filled a bucket with water and poured it over myself. And I felt released. Free.

Years later, I saw a Dutch painting. I knew nothing about paintings then; that it was a Dutch painting, that it was by Vermeer—I learnt these things later. But I was fascinated, I can remember that, by the way the painter had captured a slice of time so that I was witnessing what he had seen, a bit of life in that narrow lane in a foreign land.

So I thought then. Now I know it was not just Time that the painter had captured; I was his captive too, caught inside that picture, seeing what the painter wanted me to see.

Only the creator is free, only the creator can be free because he is out of it all. I did not know this then. I know it now.