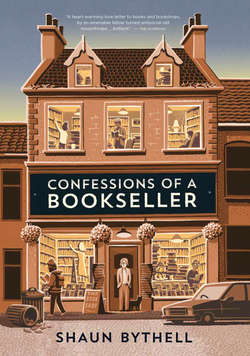

Читать книгу Confessions of a Bookseller - Shaun Bythell - Страница 33

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

February

ОглавлениеAbout 200 new books are published per week. It’s an awful thought. A body would need a deep purse to buy everything he would like to read. The fact is, he doesn’t buy. He borrows from a library.

This is the age of circulating libraries. Never before have they done such a thumping trade. I cannot agree with those who say in a deep voice that a book is not worth reading if it isn’t worth reading again. I could complete a fat catalogue of the books that are worth reading once only. This is where the public or the private subscription library comes in. Besides, if a man would like to buy a new book, but would prefer to make quite sure of it before he pays good money, he can have a quiet keek through a library copy. I whiles hear folk on the harangue about circulating libraries, and they expect me to agree because I’m a second-hand bookseller. But only a dolt would try to batter down such a useful institution.

Augustus Muir, The Intimate Thoughts of John Baxter, Bookseller

From time to time we will come across a small, cheaply produced copy of a book with a sticker—usually on the front—which says ‘Boots Library’ or, more rarely, ‘Mudies Library.’ They are usually worthless and go into the recycling, or to the charity shop, but these are the ‘circulating’ or lending libraries to which Baxter refers. Today is no longer ‘the age of circulating libraries,’ nor indeed of libraries of any sort. Prior to technological innovations at the end of the nineteenth century that enabled paper, and thus books, to be produced more cheaply, they were an expensive luxury, and only available to the relatively wealthy, and so sprung into existence the circulating library, a service by which—either through subscription or a daily charge—the less wealthy could have access to books. They were commercial enterprises, and enormously popular. Publishers and authors benefited too, as they received a share of the revenue. Their demise came in three waves: first, the reduced cost of books in the early twentieth century; then the advent of the paperback; and finally, the 1964 Public Libraries and Museums Act, which imposed a duty on local authorities to provide free lending libraries. Boots, the chemist, closed its circulating library in 1966. Scotland’s oldest free lending library is Innerpeffray Library, near Crieff, which has been lending books to the public since 1680. I share John Baxter’s respect for libraries for similar reasons—if someone reads and enjoys a library book, there’s every chance that they’ll want to own a copy of that book, so once it has been returned to the library, it’s likely that they’ll buy a copy. I can’t see that libraries could have a significantly negative impact on bookshops. If anything, the reverse. The same argument has been made about e-readers, but I’m not so sure about that.

Baxter would doubtless be astonished to discover that last year in the UK, roughly 3,500 titles were published per week. Arguably this could have a negative impact on the publishing industry—overloading the public with too many titles will inevitably drive down the numbers of an individual title’s sales figures—but I suppose it is to be celebrated that so much is being published and, hopefully, read.