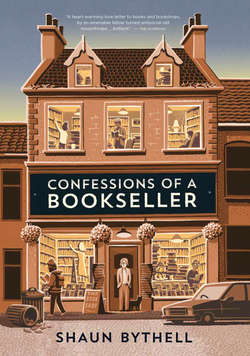

Читать книгу Confessions of a Bookseller - Shaun Bythell - Страница 60

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

March

ОглавлениеI must record that all booksellers are honest. I wouldn’t suggest anything different; not for the world. But some are more wide-awake than others. Many a time Mr Pumpherston lets a customer have a bargain, but he’s far too clever to tell him so: he always lets the customer discover it for himself, knowing fine he always does. This is the way to get good results.

Augustus Muir, The Intimate Thoughts of John Baxter, Bookseller

Augustus Muir is perhaps being unduly generous in his description of all booksellers as ‘honest.’ There are crooks in this trade, as in every other, but few people enter the book trade with any hope of growing fat on the back of it. Perhaps that is what he meant: it’s not a business from which most of us who have chosen it expect enormous financial reward. The benefits come in other shapes. In his book Bits from an Old Book Shop, published in 1904, R. M. Williamson observed: ‘The few who make fortunes by bookselling are not to be compared to the many who make no more than a modest livelihood. The happiest men in the business are not the wealthiest, but the most contented, the men who love their occupation, who look on it as a high privilege to buy and sell books.’

Oddly, though, it is when I’m buying books that I encounter the greediest people: the person selling his collection who will push to extract every last penny that they’re worth from the bookseller they’re selling them to, will inevitably be the same customer who will drive the price down to the very margin when he’s buying books. And while this is arguably good business sense, it has rather an unsavoury whiff about it. There’s no sense of fairness. Conversely, the customer who brings in books to sell and is happy with whatever you offer him will be the one who doesn’t attempt to push the price down when he’s buying books from you. Like Mr Pumpherston, these are the customers for whom I will happily round the total down from £22 to £20 without their asking, rather than those who demand reductions, pointing out minor defects, such as a small tear to a dust jacket. When I encounter these miserable fiends, my response is always along the lines of ‘Yes, there is a tear to the jacket—I factored that in when I was pricing the book. Why should I discount it twice for the same tear?’ This usually silences them, but they are the kind of people who won’t buy anything unless they feel they’ve somehow managed to negotiate a bargain. They are the worst kind of people to deal with, and I suspect that this is because, ultimately, it’s not about the paltry £1 they’re saving, it’s about power. It’s about them calling the shots, and, whether you’re an antique dealer, agricultural supplier or car dealer, it’s about the customer feeling that in the dynamic of the exchange they are in charge. They are the people who will demand a ‘bulk discount’ when they buy two books, who never tip in restaurants, who would boast about going on holiday to a place after a terrorist attack ‘because it’s cheaper.’

As far as I can see, the trick with buying, if you’re a bookseller, is to be fair and consistent. If you acquire a reputation for ripping people off in this trade, word spreads quickly and your supply will dry up. I’ve walked away from a few deals because a seller has wanted more than I have been prepared to pay, and on most of those occasions they’ve come back to me having tried several other dealers and been disappointed. Most book dealers are the same when it comes to buying, and I can honestly say that I don’t know any who would try to get away with paying a few pounds for a rare and valuable book.